Wil Sideman has a handful of belongings he holds dear. There’s the retractable fishing rod given to him by a shop technician in China, and the salmon fishing tool made of lead and carved bone given to him by a hotel owner in rural Scotland. He also has his grandfather’s handmade duck hunting decoys and his father’s hammers.

“I’m not necessarily clinging to everything, but I used to,” he said. “I have a couple [of items] that people would look at and be like, ‘Why do you have that?’ And I’d be like, ‘That is actually important.’”

In other words, objects aren’t just objects when you make them for a living. A glassblower and sculptor, Sideman’s sentimentality is of a very specific color. “Mine has more to do with human experiences,” he said. “I’m very interested in the relationships we build with each other.”

For the past four years, Sideman has been the manager and resident artist at the Martha’s Vineyard Glassworks in West Tisbury, a showroom and studio for handblown glass that has earned a devoted following for decades thanks to its distinctive, colorful designs. Sideman lives and works on-site, collaborating with other artists to produce pieces for the Glassworks gallery ranging from dishware to jewelry to ornamental fruits.

In his spare time, he creates lighting designs under the banner Eldridge & Co. – the name is a nod to his own middle name. His recognizable bulb pendants take the shapes of buoys and washed-ashore bottles and can be found in high-end homes across the Island, as well as in some restaurants. Sideman also pursues select projects of his own that pair glass with other media: two wood beams connected by a frosted glass hinge, cubed glass torrenting between rusting steel panels, glass bottles stuffed with instructions to “BREAK” in bold red letters. These pieces have been featured in galleries and showrooms in the United States, China, and Scotland.

When he works, he is constantly asking himself: “Why should this be made of glass?” Often, it comes down to the material’s unique ability to reach back in time. “[Glass] is fragile, it’s clear, it’s kind of ghostly,” he explained. “It’s easy to imagine it as something from the past.”

Part of the appeal for Sideman is that glass is notoriously difficult to work with. The challenge of the material is that it holds a grudge. “Glass has a memory,” he said. “Unlike a lot of other materials, when you’re working with hot glass, you do something to it, it remembers. If you put a sharp corner into something, you can’t really just get rid of that.”

Kind of like people, I offered.

“Yeah,” he laughed. “Kind of like people.”

Sideman grew up in Lewiston, Maine, a blue collar, ex-manufacturing town about forty minutes from the coast. He lived on his family’s farm, where needing something usually meant making it from scratch.

“There weren’t a lot of opportunities around the area. There wasn’t a lot of money,” he said. “You either went into the trades or you went into the military.... I wanted to get out.”

Fed up with working on the farm, a teenage Sideman got a job at a diner with a glassblowing studio across the street. “I was not an artistic person; I didn’t grow up with an arts background,” he said. “But I saw glassblowing, and I think the physical nature of it – the fire and the heat, [the] music and tattoos – it was exciting to me.” Suddenly, he was clocking out and heading directly to the studio, where he’d watch the artists work and try to absorb their techniques.

He left Maine at the age of eighteen to attend the Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt) in Boston, where he majored in glassblowing. Professor Alan Klein, who died in 2018, was the mentor that made him go all-in. “He got me to grow up at a pretty critical point in my life,” he said.

Sideman would go on to teach glassblowing and complete artist residencies all over the United States, as well as in Scotland and China. He was a visiting assistant professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York, where he obtained an MFA in 2013. There, he taught glassblowing to students who were hard of hearing.

Lighting, for Sideman, has been its own path, though one tightly interwoven with his career as a glassblower. After graduating from MassArt, his first job was at a lighting company making glass hardware for high-end light fixtures. This first foray into electricals lay the foundation for the work he’s doing now through Eldridge & Co., which combines the practicality of in-home lighting with rugged, nautical beauty.

For a long time, he explained, his work was concerned with the past. One of his projects was using glass and other materials to construct what he calls “narrative objects” – everyday objects that tell stories of where they have been.

“You see people there buying these fishing floats, or these old beat-up oars, and they’re putting it on their walls as a decorative thing,” he said. “I think that’s because we, as humans, know that there’s a story behind that stuff.”

He would recreate these prized but time-battered objects in glass: oars, clamming buckets, and buoys, the insides caked with bursts of dried salt crystals. When the owners of Beach Road Restaurant in Vineyard Haven – where Sideman worked as a busboy for many years – saw the buoys at a show, they asked him if he could make them into a chandelier. The twinkling buoy pendants

are still on display in the Beach Road dining room, and clients now clamor for their nautical whimsy. He has dedicated clients all over the Vineyard, he said, and he often makes several per day for people who want them in their businesses and homes.

His lighting work offers the stable income artists often lack, but it also embodies the technical precision and material fluidity that marks his artistic impulses.

“I love doing the lighting stuff,” he said. “Having a well-rounded practice helps [me] stay energized and excited about the work.”

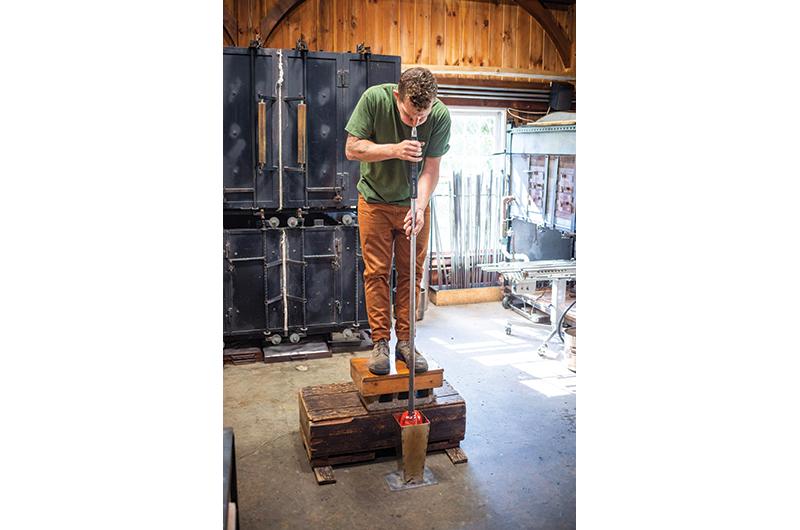

While collecting a glowing, red-hot mass out of the furnace on the end of his pipe, he explained that forty minutes of work would turn it into a buoy primed to be wired, hung, and lit. He rolled the pipe back and forth on a steel table known as a marver as his assistant blew into it, creating a bubble of air inside the cooling glass. Aside from “blow” and “stop,” they didn’t communicate much. Sideman said they don’t need to; it’s second nature.

It was back and forth between shaping and heating, furrowed seriousness gripping his features while “Kung Fu Fighting” plodded along from a speaker overhead. He torched parts of the sculpture to mold them, either with pliers or a handful of charred newspaper. He shaped the base, then the handle. Suddenly, the buoy appeared.

There is no wall separating the studio from the Glassworks gallery and store, which means visitors can see, hear, and even feel the glassblowing process when they enter. People regularly congregate at the studio’s edge to watch the artists work. Spectators clapped wildly when Sideman cracked the buoy free from the pipe and put it in the annealer to cool – a final flourish.

I asked him if the audience ever makes him nervous. “We kind of forget people are watching,” he said.

It was during Sideman’s itinerant post-grad years in 2013 that he first worked on the Vineyard. For a while, it was just one in a constellation of places that he had briefly called home. But when the previous Glassworks manager moved to California, Glassworks founders Andrew and Susan Magdanz approached him about setting down roots for good.

“I was getting tired of living out of a suitcase and bouncing around all the time, which is romantic in your twenties, but it just became a lot less [so],” he said. “I kept ending up back out here.”

The Vineyard is, in many ways, similar to the communities that pepper Maine: beholden to the harsh seasons, gripped by haves and have-nots, replete with eccentricity. What disturbs Sideman is when places like these turn into pastiches of their true origins.

“[The Vineyard] has become a destination for people because of what it was,” he said, referring to its history as a fishing community. “I think we have to be careful about not getting rid of that past and not just seeing it disappear.” He holds deep affection for the Island, he said, as it evokes his rural upbringing and affords him steady access to an artistic community.

At the Glassworks, he helped pioneer a visiting-artists program that brings glassblowers to the Vineyard from all over the world. He also mentors young people who are learning to blow glass, as he once did. One apprentice graduated from the Martha’s Vineyard Public Charter School recently and is going to college for glassblowing this fall.

“I can make my work. I can help other people make their work,” he said. “[It’s] a place that people can come in and ask questions and learn about glass and see how things are made, and that’s important to me.”

But inextricable from the joy and gratitude is a pang of Sideman sentimentality – the “human experiences” kind.

“I miss Maine all the time,” he said.

Back outside the Glassworks building, Sideman sat on the grass drinking a can of Spindrift. There was a stark, almost humorous contrast between the quaint easiness of the grounds and the studio’s white-hot toiling. On the driveway’s edge stood the garden he tends with his wife, jewelry designer Elysha Roberts.

The tomatoes, strawberries, and eggplant were on their way out, he explained; squash, melons, and pumpkins were on their way in. The cucumbers were getting “destroyed” by crows.

“We’re kind of in a funny transition right now,” he said. “There’s a lot of failures over there, but it’s kind of nice, you know? You figure out what works and what you have time for.”

Sideman’s art, too, is in transition. He said it’s been a few years since he produced a body of work. He’s preparing for a show next summer at The Workshop Gallery, the Vineyard Haven art studio he runs with his wife. The space is a sanctuary for his personal projects.

He hopes to branch out from glass into other kinds of sculpture, but he’s still nailing down the ethos. He writes about pieces or sketches them out before he starts working to pinpoint how he wants them to feel. Ironically, he said, narrative objects are a thing of the past.

“It’s a lot of these projects that are in the experimental phase,” he said. “I’m kind of seeing where they take me.”

It’s an unexpected thing to hear from someone who revels in working with one of the most unforgiving materials on earth. It’s also a refreshing contradiction; he cares deeply about the past, but he also knows when he needs to let go.

“I don’t necessarily feel like I need to define myself as strictly as I once did,” he said. “I’m doing what I’m doing.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)