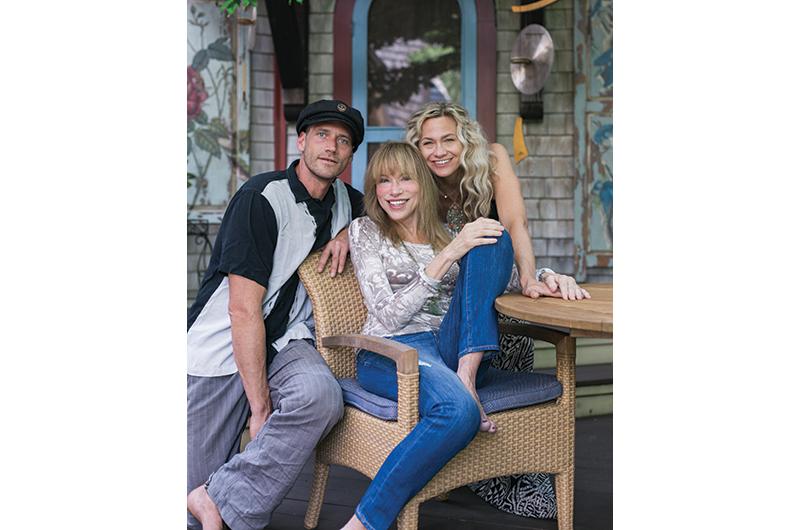

Carly Simon can’t remember exactly when the Hot Tin Roof opened. All she can remember is holding her infant son, Ben Taylor, in her arms on opening night.

In her eightieth year, the Island music maven is rarely seen out in public, let alone gracing stages and attending ribbon-cuttings. But on a particularly dreary afternoon in the doldrums of winter, she is happy to reminisce about her years as a young mother performing at and helping run the iconic Vineyard nightclub.

“I only went to the Roof if I had a babysitter,” Simon shared over a phone call from her Vineyard Haven home. Her team said she only had fifteen minutes to talk. She had just hit the hour mark and showed no signs of slowing down.

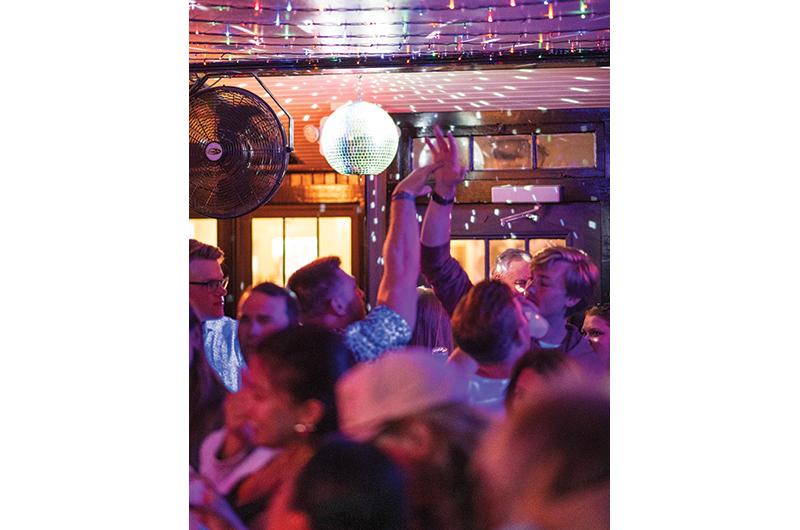

“My kids, I would put them to bed, and then I would go and get dressed and put on my dangly earrings and go out to dinner and go dancing,” she said.

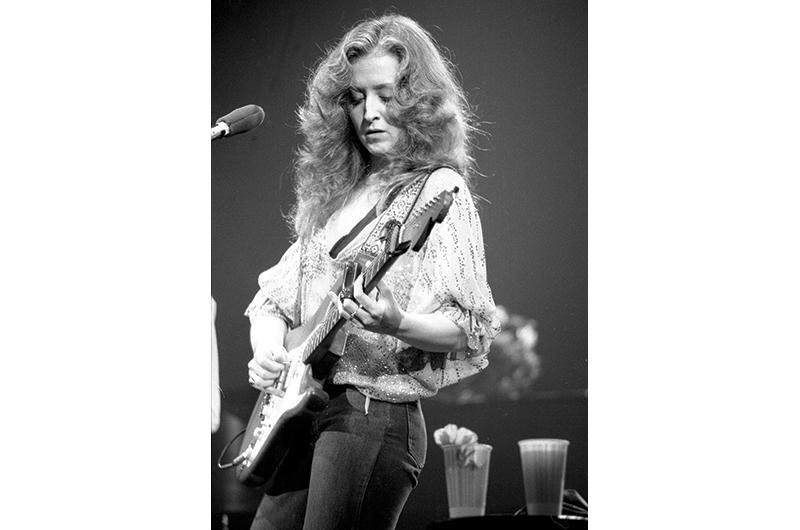

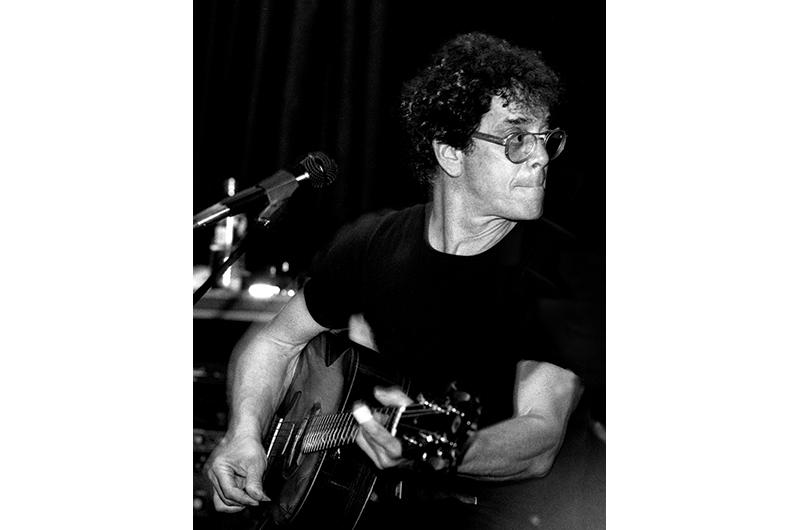

Open from 1979 to 2002, the Hot Tin Roof anchored what had been a world-famous Vineyard music scene, which Simon and her ex-husband James Taylor chaired. Simon had been approached to co-run the business by partners Herb Putnam and George Brush. She enlisted her friend and roadie Patti Rix to do the booking. In its heyday, the Hot Tin Roof hosted the likes of Lou Reed, Peter Tosh, Pat Benatar, Taj Mahal, B.B. King, Bonnie Raitt, and, of course, Simon herself.

Carved into a patch of land off Airport Road in Edgartown, the “Roof,” as it was often nicknamed, earned its name from the building’s now-iconic tin roof. Brush, who had tried to gain permits to build a dance hall–music room at the location a couple of years prior, recalled James Taylor coming up with the name “Hot Tin Roof” on the heels of the famed 1978 No Nukes concert in Chilmark. “I latched right onto it,” Brush said in an email. “Perfect, a tin building in the middle of the Island built for fun.”

“And it was hot, baby,” Simon purred.

In many ways the Roof’s run was lightening in a bottle. On one memorable night, Simon recalled a young Cyndi Lauper coming as a singer in an unknown musical group before she made it big. They hosted comedy nights with most of the original cast of Saturday Night Live, she said, from comedian Dan Ackroyd to “Squibnocket boy” Bill Murray. Her brother, Peter Simon, slung discs between live acts to save money, and visiting musicians stayed for free with a network of the owners’ friends. It also helped, as Simon’s son Ben pointed out, that it was “before people started actually caring about drunk driving.”

Despite its star-studded marquee and insider connections, the venue changed hands not once but twice in its more than twenty-year run. The first time, in 1986, it was sold to Peter Martell. Then, in 1995, facing financial trouble, it was sold to a group of investors that included Steven Rattner, Richard Friedman, Dirk Ziff, Harvey Weinstein, and Putnam. When the bottle ran dry again in 2002, there were no second chances. The Hot Tin Roof closed its doors for good in September of that year.

More than two decades later, Simon doesn’t believe any nightclub on-Island has captured the spirit of the Hot Tin Roof since, although she still holds out hope that some new venture could carry on the mantle. “The climate has to be ready for it,” she said. “The seventies were such an amazing time for music in general…. It’s a shame. I think it could find its center again here, even partially because history, it’s always returned.”

Today’s musical landscape does have at least one thing in common with the Roof, however. Subsequent nightclubs and large music venues can’t seem to stay open either. Since 2002, the Island has said goodbye to, among others, the Atlantic Connection, Seasons, Balance, the Lampost, and Nectar’s, the lauded venue that took over the Hot Tin Roof’s location near the airport before closing in 2012. The building is now home to a gourmet food shop and a fish market.

Earlier this year, Beach Road Weekend, a three-day music festival that brought big-name acts to Tisbury, announced it would not be returning to the Island after suffering huge deficits each year of operation. Instead, organizers will be seeking out a new location on the Cape for the summer of 2025. While it’s not the first time an outdoor music festival has failed to sustain a presence on the Island – in 2008 a fundraiser called the Aquinnah Music Festival lost money in its bid to bring the beat to the town – the announcement triggered alarms that venue owners and hospitality workers have been raising for years. Live music, like everything else on the Vineyard, is getting more and more expensive, threatening the Island’s legacy as a haven for musicians and artists.

“Nectar’s, Seasons, Balance, there’s a reason all of those businesses closed,” Island restaurateur and venue owner JB Blau said. “The biggest show the Island has ever seen was when Ghostface [Killah], Redman, and Method Man sold 750 tickets at Nectar’s [in 2009]…it ended up putting them hundreds of thousands of dollars in the hole…they never recovered.”

It’s not as if there is no live music on the Island. Particularly during the summer months, the Vineyard is awash with singer-songwriters, cover bands, and local legends performing nearly every night at small venues and pinch-hitting pop-ups. And yet larger venues and dedicated nightlife spots, particularly those who bring in larger acts, have struggled and continue to struggle. In the face of constant upheaval, some claim that the Island’s music scene has downsized to accommodate rising costs, favoring stripped-down daytime shows or lucrative wedding gigs over the glitzy, high-profile acts that once made regular stops to the Island. In other cases, some say public opinion has driven out much of the Vineyard’s wilder nightlife. The question then becomes: was Beach Road Weekend the last gasp of Martha’s Vineyard’s dying reputation as a live-music destination, or a misguided one-off, clearing the stage for a new act?

When Beach Road Weekend approached Tisbury to renew its permits in the fall of 2022, the event was met with backlash from abutting residents who evidently did not want free seats to a three-day music festival. Several residents, including the nearby secondhand thrift shop Chicken Alley, claimed the noise had caused their walls to vibrate. One woman held up a photo of proof that the festival had caused traffic jams; the photo showed two cars on an otherwise empty stretch of road.

For those who visited downtown Tisbury last August during Beach Road’s stay, the festival seemed to have heeded neighbors’ calls. The town betrayed an eerie quiet uncharacteristic of the typical summer rush, except, of course, for the music that emanated from the festival grounds. Inside Veterans Memorial Park, one didn’t see the muddy, free-love bacchanalia of Woodstock. Instead, a mix of older and younger patrons sipped spiked lemonades under shade awnings.

Some festivalgoers did receive medical attention. And a sharper, less impeccant nose might have detected a current of legal marijuana running through the crowd. But for the most part, the fourth iteration of Beach Road Weekend did not deliver the chaos Tisbury residents portended.

The trouble, evidently, was all backstage. When Beach Road Weekend organizer Adam Epstein announced in January of this year that the festival would be moving to the mainland, he revealed that the event had lost more than $1 million each year, even as ticket prices continued to climb. Epstein listed a litany of reasons why the Island was not well-suited to handle such a large-scale event.

For one, all equipment, stages, and amenities had to be transported over on the ferry each way. In order to accommodate ferry schedules, Epstein had to rent expensive equipment for longer periods of time, he said, amounting to hundreds of thousands of dollars in added costs. Lodging became another obstacle. The festival butted up against peak tourist season when hotel rooms and Airbnbs were still in high demand. On the mainland, hotels are motivated to do group business, offering discounts to large parties. On the Island in the last week of August, not so much.

“We had 170 security people come to the Island to work the festival, fifty to sixty professional stagehands, and then thirty site operations people – that’s hundreds of beds before you even get to the artists,” Epstein said.

Neither of these factors initially deterred Epstein, who heads the Chicago-based entertainment and events company Innovation Arts & Entertainment and has worked in the industry for more than thirty years. He got creative. He booked hotels in Falmouth and commissioned the Patriot Party Boats to take workers back and forth at all hours. It didn’t stave off the financial hemorrhaging.

“For every dollar we saved via experience and efficiencies, our costs would increase by two dollars from other factors,” Epstein said when news of the festival’s cancellation first broke. “We could never catch up.”

Other large live music ventures have met similar fates.

Blau owns three restaurants and businesses on the Island, including The Loft, a 400-person venue just steps away from the Oak Bluffs Steamship Authority terminal. In the summer of 2022, following an intensive renovation of the venue’s sound system, stage, and green room, the Loft debuted an ambitious summer lineup of off-Island artists, offering shows several times a week, every week. Epstein himself had architected the revamp; previously, the venue had earned a reputation for its shoddy acoustics, he said, a reputation it was eager to shake among artists, tourists, and locals.

“It was a spectacular failure,” Epstein said.

The Loft rarely sold enough tickets to cover base costs, Blau said, often paying out of pocket in hopes that audiences would grow with time. As Epstein and Blau both put it, there were simply too many events in the summer for visitors to drop $10, $20, $50 on a show from an off-Island artist, even if that artist could draw crowds on the mainland.

Especially when just across the street, audiences could see live music for a small cover charge.

Established in 1944, The Ritz Cafe is perhaps the last stalwart of Circuit Avenue, maintaining a tight schedule of live music five times a week even as doors shutter around them. The part-nightclub, part-restaurant, part-dive is among the only music venues open year-round, save a few weeks in February and March.

The secret to its success? Keep it small, keep it simple.

Employing almost exclusively local acts, the Ritz is crucial to keeping Island musicians afloat once summer weddings and events subside. Aside from offering cheaper entertainment, Blau said the Ritz’s size – with an occupancy of just ninety-eight to the Loft’s 400 – makes it easier to feel packed and happening. “In a venue of 400, you could have 100, 150 people and it would still feel empty,” Blau said.

For his part, Ritz owner Larkin Stallings believes the Vineyard is still a music hotspot. Stallings also manages multiple bars and venues in Houston, Texas, but the Ritz is the only venue where he’s been able to sustain a consistent live music rotation, he said.

“There’s absolutely an appetite for live music here,” Stallings explained. “There always has been.”

Yet even the Ritz, with its scaled-down operation, has had trouble booking off-Island artists. Kelly Feirtag served as general manager and set scheduler at the Ritz for years before parting ways in 2020. Even before the pandemic, when prices to pay a band or house them for the night rose, booking was always a gamble, she said. And even if a band was available, many touring bands don’t always want to interrupt their schedules to spend a night on-Island.

Covid-19 exacerbated cost issues, Stallings said, raising the price of housing and nearly everything else along with it. “It all goes back to housing,” Stallings said. “Everything.”

As in Blau’s experience, Feirtag said attendance didn’t always make the extra costs worthwhile.

“I definitely took some chances and booked some bands that were higher-priced and nobody showed up,” she said.

To be clear, it’s still possible to enjoy plenty of live music on the Vineyard. In Edgartown, The Port Hunter bar and restaurant regularly brings in off-Island musicians, and The Wharf also employs live music on the weekends. Dock Dances, a longstanding community tradition on Edgartown Memorial Wharf, gives residents of all ages a venue to move their feet. In the winter, Pathways ARTS in Chilmark hosts weekly music programming, while nearby the Chilmark Potluck Jam packs the town’s community center on a monthly basis with locals eager to hear both amateur musicians and beloved professionals. The Portuguese American Club in Oak Bluffs also hosts its fair share of local music programming throughout the year. But live music is not necessarily synonymous with nightlife – that’s particularly true on the Vineyard, where many community events wrap up by 10 p.m.

Even where nightlife venues do survive, recent legislation has made it harder to keep the party going.

In 2023, Oak Bluffs pushed up its last call from 1 a.m. to 12:30 a.m., citing concerns from the local police. At first, officers alleged that the extra half-hour – Edgartown’s last call is also 12:30 a.m. – encouraged Edgartown barflies to drive over to Oak Bluffs for one last drink. When they could or would not produce numbers on how many cars were pulled over in that time period, the argument pivoted; the town did not want to pay police overtime for the ruckus that its late-night establishments cause. The town’s new last call joins Edgartown’s as some of the earliest closing times in the country.

Oak Bluffs business owners are not happy with the change. The move shaved down already-slim profits for Island bars, Stallings said, in turn cutting out a half hour of payment that would have gone to the headlining band.

The restricted last call may have reverberations beyond Circuit Avenue, Blau said, as partygoers pour into residential districts to keep the good times going. A booming wedding industry and the rise of Airbnb and other short-term rental options can further encourage so-called “party houses,” he said. He expects the trend to continue if Oak Bluffs does not do more to revitalize its downtown scene. In the meantime, Blau, not one to swim against the tide, has shifted the Loft away from its origins as a public watering hole and now primarily rents out the space for private events.

“I welcome the day when everyone comes begging for venues to come back,” he said.

“The problem is it will be too late by then.”

Edgartown has already seen the consequences of a decentralized party scene – and has come up with an unorthodox solution to control ruckus on private property. In August 2023, parties hosted by the CEO of the whiskey brand Uncle Nearest prompted Edgartown to draft a so-called “party bylaw,” limiting the number of large events a private residence can host in a certain period of time. Though it was tabled at town meeting this spring, the bylaw would have perhaps been the first of its kind in Massachusetts.

Up-Island, Chilmark recently banned drinking at the Potluck Jam, a relatively tame event even by Vineyard winter standards, for fear of liabilities, such as underage drinking and drunk driving.

Designated nightclubs and venues, meanwhile, take on those risks with liability insurance, a cost Blau said has been the single largest expense increase for his business in the last ten years. Across the country, liability insurance rates have ballooned as insurance companies seek to offset economic inflation and a phenomenon called “social inflation,” which is just to say that patrons have gotten more litigious. “The rates keep going up because they can,” Blau said. “Especially in a 400-person venue…that’s going to cost you.”

Simon had been unaware of these recent factors curbing music and nightlife activity. When informed, she paused on the line for several breaths. “Why?” she finally asked, in a slow, grave tone. Just a few minutes earlier, she had been singing the praises of a few glasses of wine.

“Drink is a very important component,” she said. “[The Roof] would not have happened without alcohol…people are looser, more ready to take the dance floor.”

That’s not to say there isn’t a dark side to the fun. The Hot Tin Roof dealt with its fair share of liabilities, she acknowledged, from injuries to drunk driving. Drug use was fairly common too, she said, and police officers occasionally busted patrons for cocaine possession. But even while acknowledging the risks, Simon wasn’t ready to dismiss recreational substances altogether.

“It contributed to the plot of the Island,” she said. “Something mischievous, something naughty. And rock and roll needed that bit of naughtiness.

“But whatever was going on stayed undercover,” she added. “I wasn’t a part of that because I was a young mother.”

Even as the Island performs its best Footloose impression, some concerned citizens are determined to let the beat go on. Island musician Phil daRosa organizes the yearly MV SoundFest, a reggae and rock festival typically held at the end of the summer, as well as a variety of other small-scale local events and festivals. The Chilmark Potluck Jam has branched out into “Strand Jams” at the Strand Theatre in Oak Bluffs to give down-Island audiences a taste of the local music scene. And for the past seven years, Feirtag and Vineyard music veteran Rose Guerin have organized Ladyfest, a local female-led music festival and fundraiser for CONNECT to End Violence.

The festival reached its zenith in 2022 when it took over the entire stretch of Circuit Avenue, Feirtag said, but had to scale back to half the street in 2023 after some businesses complained about the disturbance. While the pushback came from only a vocal minority, Feirtag said, the opposition can make the already daunting task of putting on a volunteer-run event more challenging.

“Instead of constructive criticism, there’s often just straight-up hate,” she said.

“It can make you lose your chutzpah,” Guerin added.

Overall, residents have been overwhelmingly supportive of the event, Feirtag said, often approaching her and Guerin in the off-season to make their approval known. Ladyfest will return this October featuring a new slate of female-driven acts from on- and off-Island.

The Loft, between its rehearsal dinners and corporate retreats, does host one or two regular club nights that may portend the future of the Island’s nightlife scene. Brazilian Night, featuring an off-Island DJ, continues to draw crowds of the Vineyard’s ever-growing Brazilian Portuguese–speaking population, Blau said, and his Serbian Nights see similar success. The Ritz, too, increasingly relies on cost-effective DJ sets to fill out its weekly lineup, as does Eleven Circuit (the site formerly known as Flavors) across the street. As he’s observed in his Texas venues, Stallings noted that DJs can accommodate a much more diverse set of genres than live bands.

The problem, then – at least in part – comes down to live music. In their combined decades of experience in the Island music scene, both Guerin and Feirtag admit that keeping the beat alive hasn’t always been easy. The Vineyard hasn’t seen a destination music venue since Nectar’s, Feirtag and Guerin said. But that doesn’t mean one couldn’t suddenly spring up from the Airport Business Park.

“I truly believe anything is possible on the Vineyard,” Feirtag said. “It sounds crazy, but it’s true…you could meet anyone at any time and make something happen.”

Through the ups and downs, Feirtag remains staunchly optimistic about the Island’s ability to adapt and evolve, whether it’s facing more pressing issues, such as climate change and housing insecurity or threats to its once-thriving but still vibrant artist community. Guerin pointed out that governments in Europe have entire cultural budgets, with the goal of supporting its local artists. The aid not only helps individual artists, she said; it also cements art not just as something to enjoy in your free time but as an essential public good.

“It shows that it’s important to the community, to the life and the vibrancy of your community,” Guerin said.

If it’s difficult to think of a weekend music festival or a night out at the bar as art, Stallings said that might be because the majority of Vineyarders haven’t gone out in a while. The same late-night revelers at the Roof haven’t left the Island – they’ve just gotten older.

“People forget what it’s like, how much a night out means when you’re young,” Stallings said. “It’s where you let loose after work. It’s where you make friends. It’s where you meet your next ex.”

Simon has gotten older, too, but she hasn’t forgotten. The exact dates may be fuzzy, but she remembers the feeling – and how important it is for others to take part.

“There’s gotta be a money person who’s willing to lose his shirt a little bit,” she said. “It would be great to give this Island something as memorable as a night at the Hot Tin Roof.”

And as far as any moral qualms some might have against those looking for music, drink, and a little bit of late-night action, Simon shrugged them off.

“We weren’t saints,” she said, “but we weren’t sinners.”

The print version of this article incorrectly stated the year in which Adam Epstein field for nonprofit status for his MV Concert Series. That occurred in 2020, not during the third year of the Beach Road festival. The article has been updated. We apologize for the error.

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)