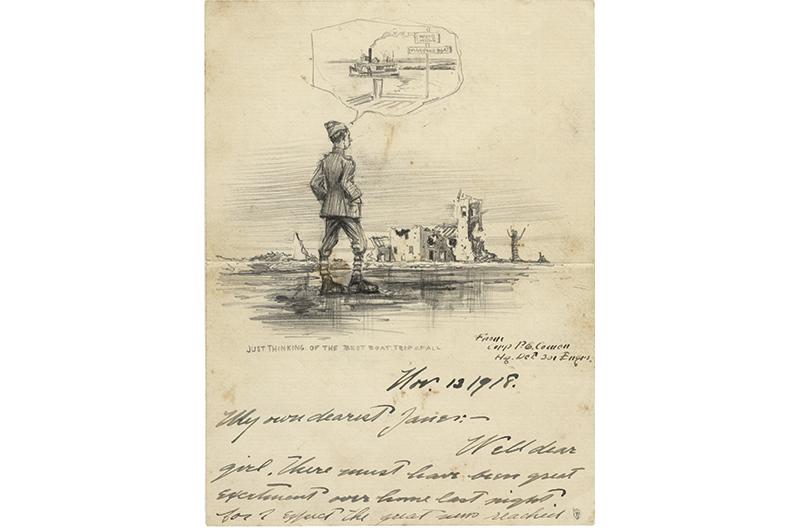

In eastern France, September 1918, after the marching was done for the day, Corporal Percy Cowen penned a letter home.

“My own dearest Jane,” he wrote to his wife back in Chilmark. “All the time things are looking brighter and brighter for the Allies…there is only two things I want, and one is to see Germany smashed and the next is the returning to my dear wife…when I think of you and home it seems like a great dream.”

An artist by trade, Cowen would complete his message in elegant cursive hand, but for one detail. No letter was finalized without an illustration depicting his vision of life in the army in wartime Europe.

For more than a century, Cowen’s descendants lovingly preserved those letters, holding fast to the family history contained within, as well as the artistic talent they displayed. And yet few outside of the family ever gained a glimpse. Indeed, in the decades that followed, Cowen’s name – once well-known and respected in the vibrant New York and Chilmark art scenes – fell out of use. A contemporary of George Brehm and Thomas Hart Benton, Cowen’s own artistic accomplishments, legacy, and influence were all but forgotten. Even among his family, the details of his short biography were little discussed.

“My grandmother, she talked a little bit about him, and there was some stuff in her house, paintings and stuff that she had collected,” recalled Danny Whiting, one of Cowen’s grandsons. “But that’s about all – she never spoke about him much.”

This year, the family decided to make Cowen’s name known.

“We felt like he should have his name out there, be seen,” said the celebrated Island-based painter Allen Whiting, another of Cowen’s grandsons. A landscape painter par excellence who has inspired and mentored many younger Vineyard artists, he considers Cowen to be his foremost influence.

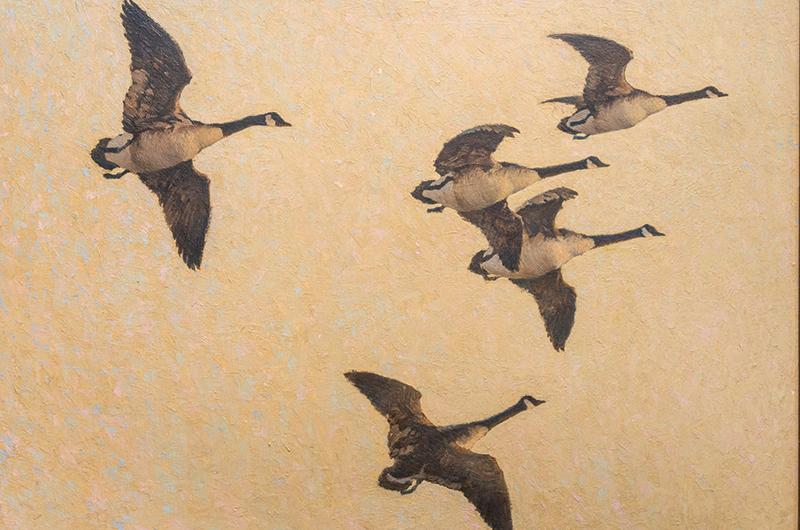

And so this spring, better late than never, Allen, Danny, and their sister, Prudy Whiting, collaborated with the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in Vineyard Haven on the first-ever exhibit of Cowen’s work. The small collection fills just one room but spans the artist’s lifetime and various styles. Joyful, colorful sketches mix with pen-and-ink drawings. Vivid illustrated magazine covers hang alongside evocative whaling scenes, quiet stands of trees, and flocks of geese. Impressionistic landscapes mix with bold, modernist portraits.

Taken together, they paint a portrait of an artist on the move: one exposed to vibrant, changing art scenes; one who was just beginning to experiment with new techniques; and one who was building a home and a family on the Island when he was shipped overseas and his life took a drastic turn.

In one wartime illustration that perhaps best displays his state of mind during this time, Cowen sketched an American soldier surveying the wreckage of war. A cartoon bubble suspended overhead, he dreams of the ferry home.

Cowen would achieve that dream, but only briefly. A few years after he returned to the Island, and thirteen months after his only child, Jane, was born, he would succumb to cancer. He was thirty-five years old, a promising and successful young artist, with a career cut all too short.

Although Percy “Perc” Cowen spent his last days on the Vineyard, his life began in 1888 in another New England nautical community: the town of Fairhaven, just outside of New Bedford.

“Probably no marine artist in the country had a more propitious early environment than Mr. Cowen,” wrote the New Bedford Standard in his 1923 obituary, which the Vineyard Gazette republished with the headline “Soldier-Artist Mustered Out.”

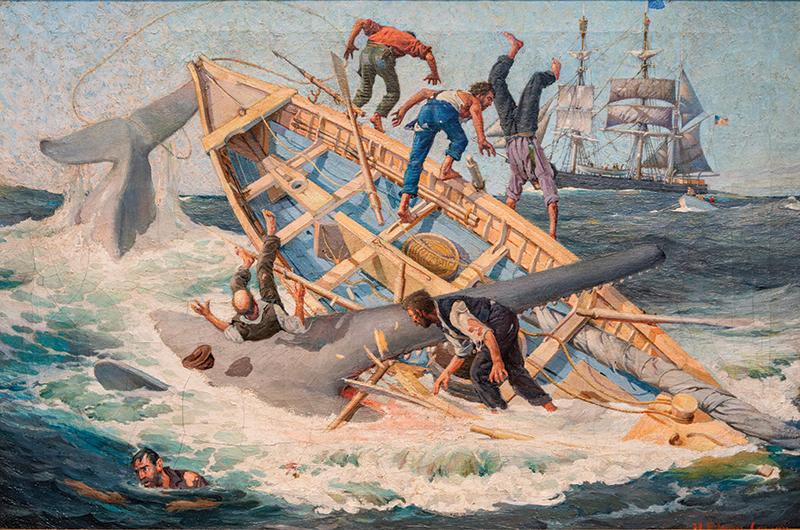

“He was from a whaling family,” explained Bonnie Stacy, curator of the exhibit, and Cowen grew up with tales of his family’s maritime legacy.

Relatives on both sides were commercial fishermen, and Cowen himself even spent a season fishing. After a brief stint, however, he returned to his childhood love of artwork and enrolled at the Eric Pape School of Art in Boston, then at the Art Students League of New York.

Scenes of sailors and fishermen would figure constantly in his career. One painting, an imagined scene of harpooners in a small boat being capsized by a sperm whale, now belongs to the New Bedford Whaling Museum. It is on loan to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum for the exhibit.

“Thus surrounded by those whose stories thrilled him as a boy and left their imprint on his life,” wrote the Standard, “it is not unnatural that he should bring this stirring life to his art.”

While tides and maritime scenes would define much of Cowen’s work, it was, in fact, in the bustling streets of New York that the artist came into his own.

“He must’ve seen a lot in New York, when the Art Students League was thriving,” said Whiting, the artist. “I’m sure he went to the [1913] armory show in New York, where modernism kind of came into this country, and he obviously picked up on it.”

Whiting has perhaps spent more time examining Cowen’s work than any other living artist. Though he never met the man (Cowen died well before he or his siblings were born), he spent

his childhood learning from Cowen’s techniques.

“We had these paintings up on the wall, and that was my art education,” Whiting said. Later on, he and fellow artist Bill McLane would line up a Cowen painting next to their easels, a humbling practice they called the “schoolyard corrective.”

Although Cowen didn’t leave accounts of his own artistic influences, Whiting said you can almost see the era through his work. These were the heady years of the early twentieth century when impressionism and realism were taking hold in America and the names of Frederic Remington and George Bellows loomed large.

“I’m sure it was a good competition,” Whiting speculated. “But I always like his stuff the best of what I saw.”

Artistic competition and inspiration don’t pay the bills, however, so Cowen turned to commercial art and illustration. In its obituary, the Standard noted “the struggle in New York”: “the battle of an unknown artist making his way from editor to editor with his portfolio, hoping against hope that his pictures would sell, believing in their worth.”

“It was pretty rough weather for a time,” Cowen once recalled, but “at last, I sold an illustration…to Rutter’s Magazine, and they paid me $25 for it. My, but that looked big then.”

The era has since been dubbed the “golden age of magazine illustration,” said Stacy, noting that Cowen’s career coincided with the first of Norman Rockwell’s iconic Saturday Evening Post covers. “Photographs were not as common in magazines then,” she said, with most stories and covers then supplied with hand-drawn visuals.

The young artist carved out a niche for himself, focusing on illustrations for maritime stories, a popular topic at the time and one he had been engrossed in since childhood. It was on the Vineyard that Cowen found some of his best subjects.

“Menemsha was still an old-fashioned fishing village then,” Whiting said, the perfect town to find reference for his stories. Menemsha shacks and fishing weirs and portraits of Island notables all appeared in the pages of national magazines, albeit stripped of their context.

“He would do portraits of people he knew on the Vineyard, because they were convenient,” Stacy said. Cowen also used himself, photographed in various action poses, as a key reference.

These are the compositions that make up the bulk of Cowen’s career, as well as the museum exhibit: dynamic scenes painted on artist board to be transferred onto magazine covers. In addition to Cowen’s own pencil marks, they feature notes on how the paintings should be adapted to the glossy page. But hung on the museum walls, they serve as artworks in their own right: luminous crashing waves, bright Menemsha sunshine, naturalistic portraits of Vineyarders in oil and charcoal.

Clearly, the Island was his muse.

While little is known of how the artist first came to the Vineyard, Stacy suspects he learned of the Island through the New York art scene, some of whom were then discovering the virtues of a Chilmark art retreat.

“He was sort of familiar with a lot of artists who worked in New York,” she said. “One person from the group comes, and then another, and then they get a place together.”

Among his peers were brothers George and Worth Brehm and, after the war, Thomas Hart Benton.

“The people of the Vineyard…knew and respected him as the dean of the Chilmark art colony and a generous host,” his obituary wrote. “His cottage was a mecca for visitors whose names are by-words in the art and journalism professions.”

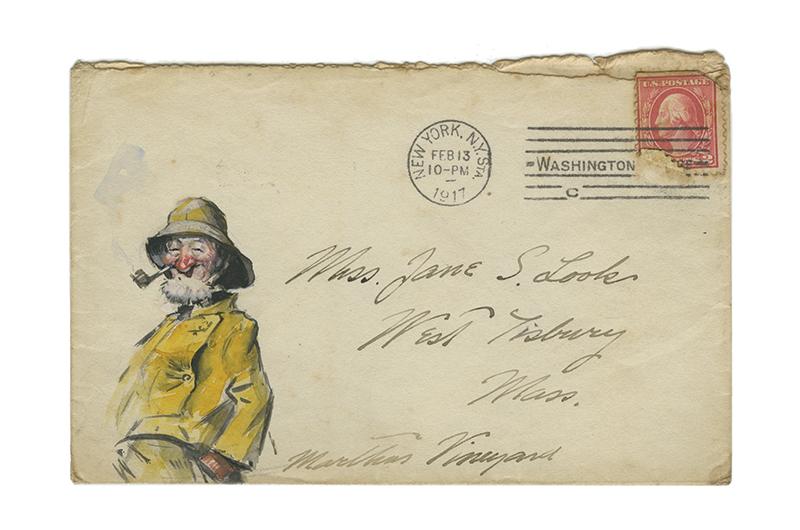

It was also on the Vineyard where he would meet his wife, a local girl, Jane Look, whose own family on the Island dates back to the 1600s. The couple shared only a short honeymoon; they were married for three weeks before Cowen crossed the Atlantic to join the Allied offensive with the 301st engineers’ division. Upon his return, for the remainder of his short life, the pair split their time between New Rochelle, New York, and Chilmark.

“Somewhere on the Atlantic I am now, heading for Europe,” he wrote in one of the first letters home. “It seemed we were no more than off the south of Noman’s Land looking seaward…how I wish we were as near as that to Martha’s Vineyard.”

Cowen’s letters to his wife are an intimate account of his time in the service. He writes of the minutiae of everyday life and the destruction that war had wrought, of the price of bananas in France, and of shells that rained from the sky.

As part of an engineer’s unit, many of Cowen’s duties were well suited to his artistic skills, assigned to making maps and painting catalogue designs. At the end of the war, he even illustrated a pamphlet on his unit’s history. Even so, he typically omitted the worst of his encounters in his letters, in order to spare his wife the worry.

“He probably took pride in a lot of what happened,” said grandson Danny, who was stationed in Korea for the U.S. Army in the mid-1960s. “I know it was a horror in some of those trenches. I mean, all war’s a horror, but that was really something.”

One of Cowen’s military portraits now hangs in the American Legion building in Vineyard Haven, he said, where Cowen was a member.

But of all the topics Cowen took up in his letters, homesickness was perhaps the most frequent. “When you wrote about going to Lobsterville…you said you got some beach

plums,” he wrote. “Are they very thick this year? How I like to go after them. If there are any next fall and I am home…how I would like to go after some with my dear girl.”

Even more vivid than his words were his images. Intricate line sketches of the European countryside and eerily quiet bombed-out structures appear alongside colorful, lighthearted cartoons of soldierly life. Landscapes, too, appear among the pages – a new form for Cowen, a presage of the next and final phase of his short career.

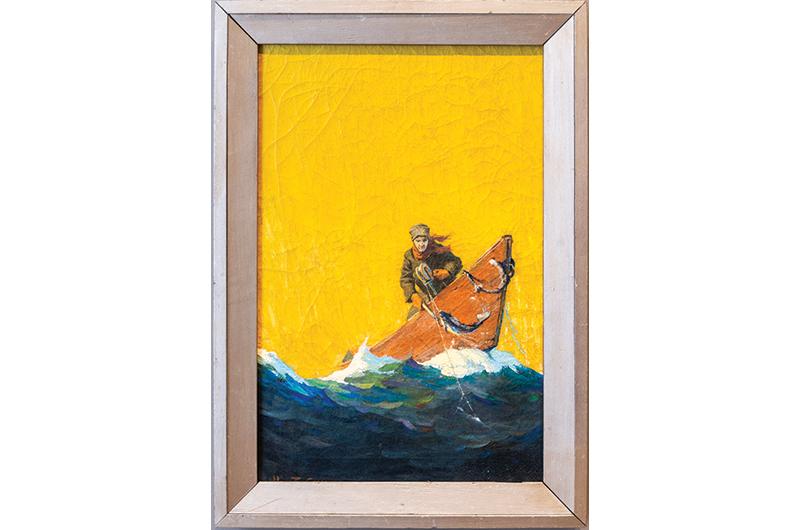

In the last year of his life, Cowen largely turned away from the magazine illustrations that had defined his earlier work. Gone was the dashing dynamism and bright contrast of his commercial output, the dramatic figural scenes that paired so well with maritime tales and magazine stories. Cowen, in these last works, was in an altogether more contemplative mode.

Gone, too, was the strict realism of Cowen’s early paintings, replaced with a more relaxed, impressionistic approach to color and composition. “They’re really different from the sort of thing that you see in the illustration,” Stacy said of the landscapes. “It’s not the same kind of a feel.”

Although Cowen’s tendencies toward impressionism – mottled colors and delicate, splotchy brushstrokes – appeared in his earlier work, it is in this time period that the artist really began to put those techniques to use.

Stark harborside light was replaced by an orange luminosity, such as in a painting of geese soaring across a metallic sky. The rousing human action that paired well with magazine stories was swapped for the serenity of Vineyard dusk.

According to Whiting, this shift might have been brought on by a certain clarity of purpose. “He had quit illustrating and had come here, moved here, stayed here, just to get into landscape,” he said, recalling a conversation he had with artist Benton, who had become close to Cowen by then.

“I think [Cowen] knew he was dying already,” Whiting said.

As Cowen’s obituary tells it, a forced march at the end of the war led to an infection and medical complications. He was eventually diagnosed with sarcoma, leaving Cowen in bad health for the last year of his life.

His death in 1923 cut short a burgeoning artistic dialogue between him and Benton, a collaboration Whiting theorized may have contributed to Benton’s own artistic development.

“Benton moved here, and he’s in his thirties. He had just come from France. But he didn’t know what he wanted to do,” Whiting said. “Then they hooked up in Menemsha and painted together for a couple of years. And then [Cowen] died, and Benton just kept on painting what became regionalism – I feel like that’s kind of where [Benton] got his start.”

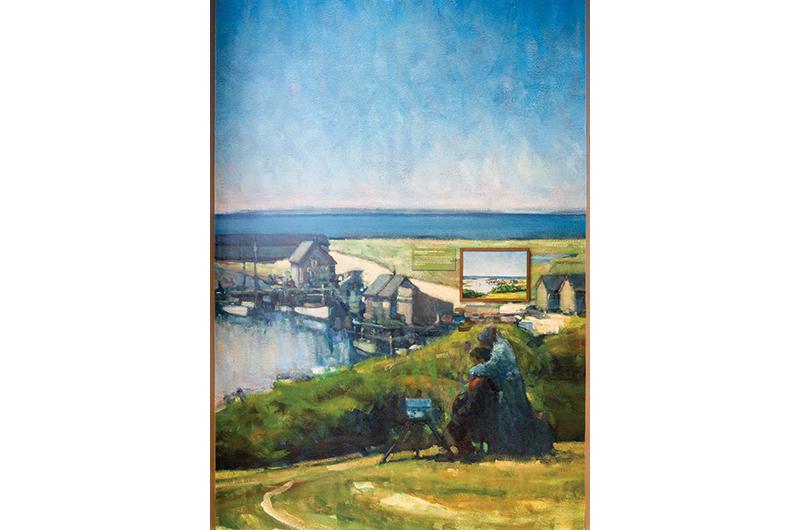

Regardless of his connection to the regionalist art movement, one lineal connection in the contemporary art world is clear. Whiting’s own serene, subdued, colorful Island landscapes reflect the influence of Cowen’s final works, albeit in a more impressionistic style than Cowen ever dared.

Alongside his indirect influence, Whiting has also created another artistic tribute to the grandfather he never met: a riff on Cowen’s painting Menemsha from Creek Hill.

Cowen himself is the subject of Whiting’s rendition. In it, Cowen’s plein-air easel is set up on the hill, his wife and young daughter nestled beside him. All three are looking out toward the sea.