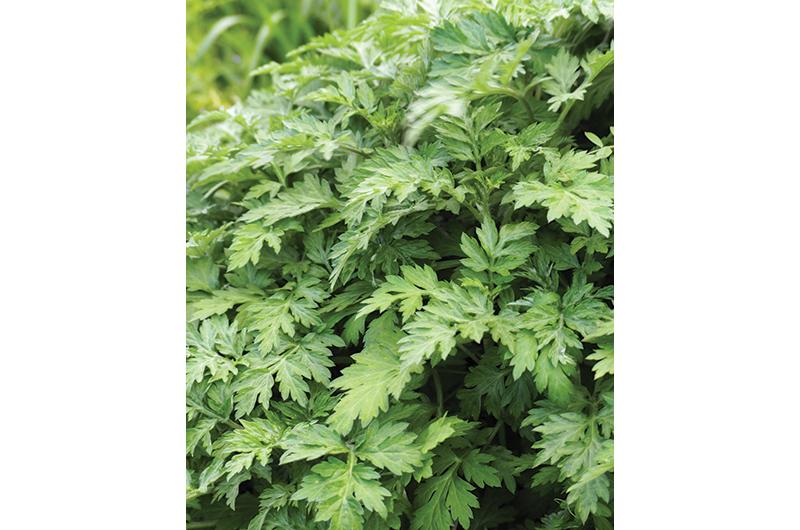

Their agenda for world domination is well-known to gardeners across New England. With their various powers combined, invasive plant species can withstand drought, flooding, and extreme damage. They can thrive in even the most adverse conditions. Even after an inspired whacking, they can take down fifty-foot trees, tear through pasture, and grow and spread and multiply as if with Satan’s blessing.

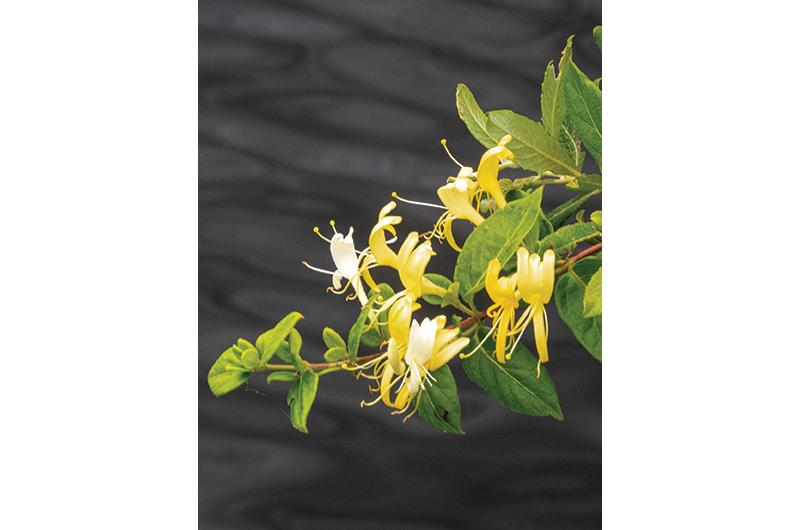

According to the Island’s naturalists and land managers, invasive plant species – not to be confused with weeds – are an often-underestimated ecological threat. Asiatic bittersweet, autumn olive, Japanese knotweed, mugwort, and honeysuckle, to name just a few of the plants that weren’t originally native to the Vineyard but have become naturalized here, have been known to choke out local species and drive down biodiversity. They’re also bears to remove.

At Mass Audubon’s Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in Edgartown, a 194-acre nature preserve containing woodlands, meadows, ponds, and salt marsh, Suzan Bellincampi, regional director of Mass Audubon, has been fighting invasives since she arrived to the sanctuary seventeen years ago. Nonetheless, the organization still struggles with invasives that have taken root. Walking the trails with her in the colder months, many of those plants appeared to be bare twigs and skeletal brushes. But in spring, they come back with a vengeance.

“They have one biological imperative,” said Bellincampi. “To survive.”

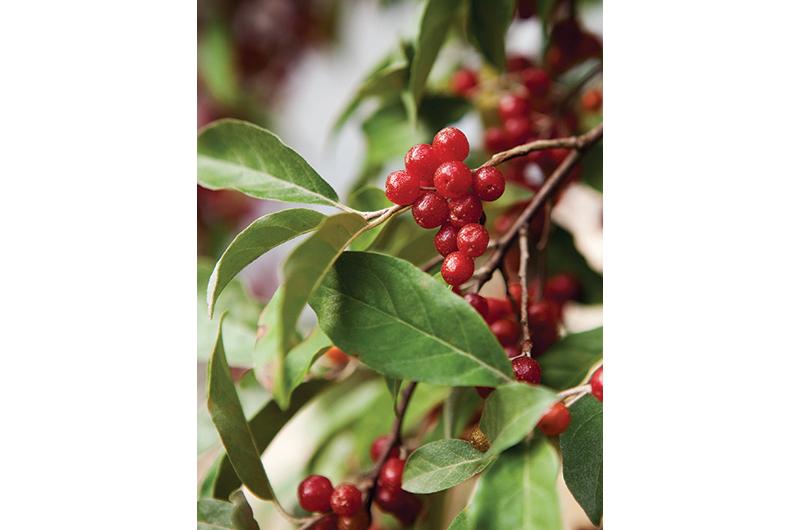

She pointed to a snarled vine that curled up a pitch pinetree. Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus): a plant that originated in eastern Asia and spread to the United States in the 1860s. Once you see it, she said, you begin to notice it clinging on to half of the trees in any given Island forest. The twiggy, round-leafed plant bears festive red berries in the fall and winter, and unwitting foragers sometimes harvest them for their Christmas displays. But if left unattended, bittersweet can climb up and strangle its host tree and even crowd out the shrub and ground cover below it. On the sanctuary premises, it is one of the factors responsible for the decline in milkweed, a major food source for migrating butterflies.

“It’s one of the worst,” she said, “and very difficult to remove without removing the host tree with it.”

Nonetheless, said Bellincampi, the best time to try to do so is in the spring or early summer. When plants are young, gardeners can pull out bittersweet by hand, provided the soil is moist and they make sure not to leave any seedlings behind. The work is made lighter with more hands. Last fall, students from the Martha’s Vineyard Public Charter School helped clear invasive species from the sanctuary’s forest, hand-pulling bittersweet, autumn olive, and shrubs of honeysuckle. But once the vines have taken hold, extermination becomes a near-Herculean

(or perhaps Sisyphean) task.

The Greek myth of the Hydra – a snake-like monster whose head, when severed, sprouts two more heads in its place – also comes to mind. When cut, bittersweet vines can resprout even more aggressively as the plant seeks to recover lost ground. To stem the backlash, gardeners and ecologists recommend persistent pruning coupled with doses of topical glyphosate, a herbicide often used in agriculture. By applying small amounts of herbicide to the cut vine, one can stave off regrowth and eventually starve out the plant. It’s a process that can take years of repeated efforts, and the herbicide is costly and can only be applied by a licensed professional. Bellincampi pointed to some mounds of dirt where bald roots have started to sprout.

“You can see some of it is already starting to grow back,” she said.

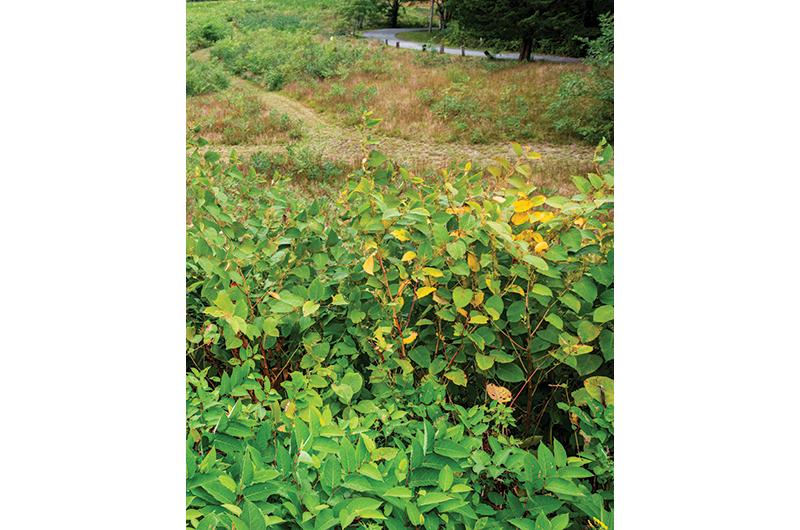

It’s a similar story for the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission, which manages 4,000 acres of conservation land around the Island. Since 2013 the organization has employed a herd of goats to help manage plants on its properties, but invasive Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica), a bamboo-like plant found in most parts of the Vineyard, has proven particularly difficult to eradicate. For the past two years, the land bank set its goats on a patch of knotweed at Pecoy Point Preserve in Oak Bluffs and allowed them to graze four separate times.

“So far we have not seen a change,” land bank ecologist Julie Russell said.

And last fall, the town of Aquinnah debated how best to handle an infestation of Japanese knotweed around one of the town’s water tanks. Known for its tenacity, its shoots can grow through weakened concrete and its root network can spread up to thirty feet. The growth was so advanced, Aquinnah town officials warned, that the plant could envelop and potentially break through the town’s water tank if left unattended.

Months later, conservation commission chair Sarah Thulin said the town is still weighing several paths forward. Cutting the plant would only make it grow back stronger, she said, and excavation would require coordination between the town, ecologists, and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), whose property abuts the affected tank.

The one option entirely out of the count is herbicide, Thulin said, since the area is too close to Herring Creek and other wetlands. “It’s going to take time to come up with a solution that

works for all parties,” she said.

While getting rid of invasive plants is a conundrum, it’s much easier to determine how they got here in the first place.

Many of the plants plaguing gardeners and land managers today, such as Japanese knotweed and honeysuckle, arrived to the Island in the late nineteenth century, around the boom of Victorian gardens favored in summer homes across the U.S. Home gardening had been a popular pastime for decades, borrowing from European and, later, Japanese tradition. It’s no coincidence then that most invasive species on-Island came from either Japan or Europe and, in fact, were chosen because they grew well in the New England climate.

Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata), a shrub-like plant with red, silver-flecked berries, was brought to the U.S. from Asia in 1830. It was planted on the Island (as well as throughout Massachusetts and other states) in the 1950s as a means to reduce erosion, Bellincampi said. The same hardy root system that digs deep into dunes, it turns out, makes it a bugger to excavate.

Invasive plant species are not just plants that are difficult to control, Bellincampi explained. They are typically plants that have come from off-Island – usually an entirely different continent – and begun to take over the landscape’s indigenous flora. The distinction is perhaps best illustrated by two ubiquitous and iconic species found on the Vineyard: the beach rose (Rosa rugosa) and poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans).

Although it’s hard to imagine the Island’s summer coastline without the faint scent of beach rose, the beloved flower is invasive and has existed on the Island for less than 200 years. Popular among sailors for its high vitamin C content, the plant is thought to have been introduced to the region by a shipwreck on Nauset Beach on the outer Cape. Following the wreck, the fruit, which can float for quite some time, washed up on Island shores. It has proliferated ever since.

Widely reviled poison ivy, meanwhile, is a Martha’s Vineyard native. Although toxic to humans, poison ivy is an important source of food for many native insects, who in turn become food for birds. “It plays a role in its environment,” Bellincampi said of the ubiquitous purveyor of rashes and blisters. “It all goes up the food chain.”

Many invasive plants, by contrast, contribute little to the food chain or even disrupt the balance of species in a given ecosystem, Bellincampi said. Dropped into a strange land and charged with nature’s all-consuming imperative to survive, they do just that, edging out native plants critical to the local environment in the process. Native insects, in turn, are sometimes less likely to recognize them as a food source, causing a jam in the food chain.

Some biologists, however, have challenged the idea that invasive species are entirely harmful to the environments they’re introduced. Species exchange has occurred for millions of years, after all, although not nearly at the same rate as it occurs today.

In his book Where Do Camels Belong?: Why Invasive Species Aren’t All Bad (Greystone Books, 2014), biologist Ken Thompson posits that in the age of globalization, it’s impractical to try and reverse the tide of biological exchange. In fact, he argues that many extermination efforts, such as pesticides, can cause more harm than just leaving well enough alone.

There are also cases in which invasive species – or, as some biologists call them, introduced species – even benefit their new homes. Autumn olive, bittersweet, and honeysuckle are considered invasive, but have become a significant source of food to fruit-eating birds. The fact that those species can thrive in the winter ensures more bird species can too.

Similarly, honeybees – often touted as chief pollinators in the United States – are nonnative species, and yet many plants still rely on them as more and more pollinating species continue to decline. In turn, insect species have learned to pollinate some invasive plants, such as Japanese knotweed, although it primarily spreads through its root system.

A 2015 study by the Society for Conservation Biology pointed out the paradox of modern conservation: now that global ecosystems have become increasingly tangled, one ecosystem’s invasive species may be endangered in its native environment. If the goal is global conservation, how do we assign value to one species over another?

The fact that some invasive species were introduced for ecological purposes is not lost on experts in the field – the autumn olive being a prime example. In the past decade, Island conservationists have struggled with the reality that most coastal dunes are shored up with existing nonnative species, such as autumn olive and beach rose. Tearing up the large tracts of shrubbery would erase decades of coastal resiliency.

“There are no absolutes,” former Oak Bluffs conservation commission chair Joan Hughes said in 2011. “Conservation commissioners have to separate any advocacy and personal points of view from their regulatory role. Everything in life involves some compromise.”

Like it or not, we humans are making choices that impact the environment. The plants certainly didn’t ask to be here.

Today, humans can spread invasive species less deliberately than through actively planting them in their gardens or landscapes. For instance, invasives arrive through the use of nonnative soil containing seeds and rhizomes of all kinds of plants. For that reason, ecologists are careful to use native soils ideally from the Island itself.

Polly Hill Arboretum in West Tisbury is one source for those soils and a major advocate for native plant gardening. Its executive director, Tim Boland, has spoken extensively on the dangers of too much outside interference on the fragile Island ecosystem. The arboretum has managed to avoid issues with invasive plants largely because of their closed soil and compost system.

“Even a small segment [of root] will cause a new plant to emerge and spread,” he said.

Contagion isn’t always something gardeners – or even land managers – can control. Often, invasive plants spread from abutting properties, potentially prompting awkward conversations with neighbors.

“They’re usually pretty good about it,” Bellincampi said of the few times she’s had to talk to abutters about encroaching plants coming into the sanctuary’s territory. “But it just goes back to being aware about what you plant and what you’re bringing into your environment.”

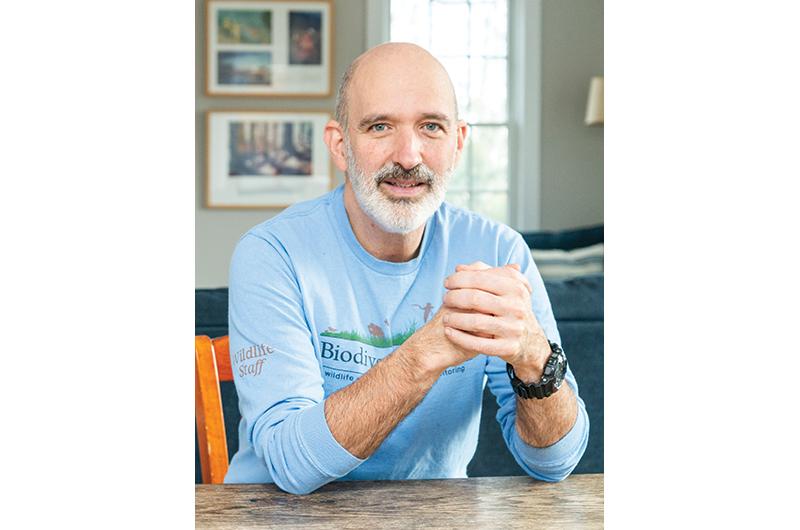

For those looking to tend their own garden, help is available. Richard Couse is the program director of Natural Neighbors, a program run through the Island ecological nonprofit BiodiversityWorks. Through Natural Neighbors, Couse consults with gardeners on how to increase the native biodiversity in their gardens. Over time, however, he noticed homeowners often needed an extra hand.

In spring of 2023, Couse started the Invasive Plants Brigade, an offshoot of Natural Neighbors in which volunteers trade off clearing pesky species from each other’s yards. Advanced infestations are often too daunting for a homeowner to tackle on their own, Couse explained, but a team of volunteers can pull out even the fiercest shrubs in just a few hours.

When a volunteer signs up for an outing, they automatically bank a day the brigade comes to their garden. So far, the program has twenty regular volunteers, but Couse plans to reinvigorate participation in earnest this spring, when plants are young and vulnerable.

The size of the program is limited to what Couse himself can handle, but its success has led him to wonder why the landscaping industry, with its colossal footprint on the Island, has not expanded more into invasive species management. There are, however, a couple of companies on the Cape that specifically deal with invasives.

“It’d be good for business,” Couse said. “It’s work that never ends.”

Inside or outside of the home, both Couse and Bellincampi urge constant vigilance to uproot wayward plants before they get out of control. Some varieties, such as knotweed, mugwort, and autumn olive, are edible, and can be eaten as a form of species mitigation. Knotweed is harvested in the spring, producing red shoots that taste like rhubarb, Bellincampi said. Autumn olives are tart and plum-like and make good cordials.

“Anything you can do with a beach plum you can do with autumn olive,” she said.

While out foraging, phone apps such as PictureThis, Pl@ntNet, and iNaturalist can be used to quickly identify invasive species at the snap of a camera.

Once Islanders begin to take more notice of the vegetation around them, they might start to realize when things are amiss, Couse said. Plant life doesn’t get the same PR as higher-profile species, such as polar bears and pandas.

“Most people don’t pay much attention to plants,” Couse said. “They just look out of the car window and see green.

“Getting to know your environment is the first step to starting to care about it and see yourself as a part of it,” he said.

Oh, and watch out for poison ivy.