In 1962 Lela Mae Williams boarded a bus for Massachusetts accompanied by her nine youngest children. She had been promised a better life – guaranteed housing, a job, even a personal welcome from then-President Kennedy. But when she arrived in Hyannis, she discovered she had been the victim of a cruel political joke. Her fare had been paid for by a network of white segregationist groups known as Citizens’ Councils – basically “the Ku Klux Klan without the hoods and masks,” as historian Clive Webb termed them in a 2020 interview with NPR.

In 1962 Lela Mae Williams boarded a bus for Massachusetts accompanied by her nine youngest children. She had been promised a better life – guaranteed housing, a job, even a personal welcome from then-President Kennedy. But when she arrived in Hyannis, she discovered she had been the victim of a cruel political joke. Her fare had been paid for by a network of white segregationist groups known as Citizens’ Councils – basically “the Ku Klux Klan without the hoods and masks,” as historian Clive Webb termed them in a 2020 interview with NPR.

The scheme was a parody of the previous year’s Freedom Rides, in which civil-rights activists had attempted to integrate bus terminals throughout the South. Members of the Citizens’ Council alleged that activists didn’t actually care about Black people and were just using the issue to drum up votes. They hatched a plan to transport unemployed, welfare-dependent, or recently incarcerated African-Americans from the South to call the Democrats’ bluff.

“For many years, certain politicians, educators, and certain religious leaders have used the white people of the South as a whipping boy, to put it mildly, to further their own ends and their political campaigns. We’re going to find out if people like Ted Kennedy… and the Kennedys, all of them, really do have an interest in the Negro people, really do have a love for the Negro,” said Amis Guthridge, one of the architects of the plan that became known as the Reverse Freedom Rides.

All told, the Citizens’ Councils duped more than 200 Black citizens over the course of that summer, delivering most of them to Hyannis, near the site of the Kennedy compound. But their plan to sow division didn’t work. Instead, a team of Cape Cod volunteers, church leaders, and members of the local chapter of the NAACP stepped in. They helped the Reverse Freedom Riders find housing and jobs. “They were homeless, broke, tired, and afraid. We had to help them,” the Rev. Kenneth Warren told a reporter at the time.

As word of the response in Hyannis spread, businesses and professional organizations staged boycotts. The New York Times called the program a “cheap trafficking in human misery on the part of Southern racists.” Even some segregationist papers and radio stations began calling it a sensationalized stunt. By October, money dwindling and public opinion strongly turning against it, the Reverse Freedom Rides fizzled out.

If only we could say the same of the parallel situation unfolding today, in which tens of thousands of migrants have been fed false promises, used as political pawns, and transported from Texas and Arizona to Democratic strongholds throughout the country – including Martha’s Vineyard. That effort shows little signs of letting up.

It’s easy to get disenchanted by this repetition of history, to draw the conclusion that we haven’t learned from our past and that our political divisions are only growing deeper. And yet there are reasons for hope. The story of the Reverse Freedom Rides is not just a tale of how the country continues to wrestle with the same demons six decades later, Webb told NPR. It is also a template for how average citizens can, and did, foil a racist plot.

“The white conservatives who were behind that campaign then actually underestimated the decency of many ordinary people,” he said.

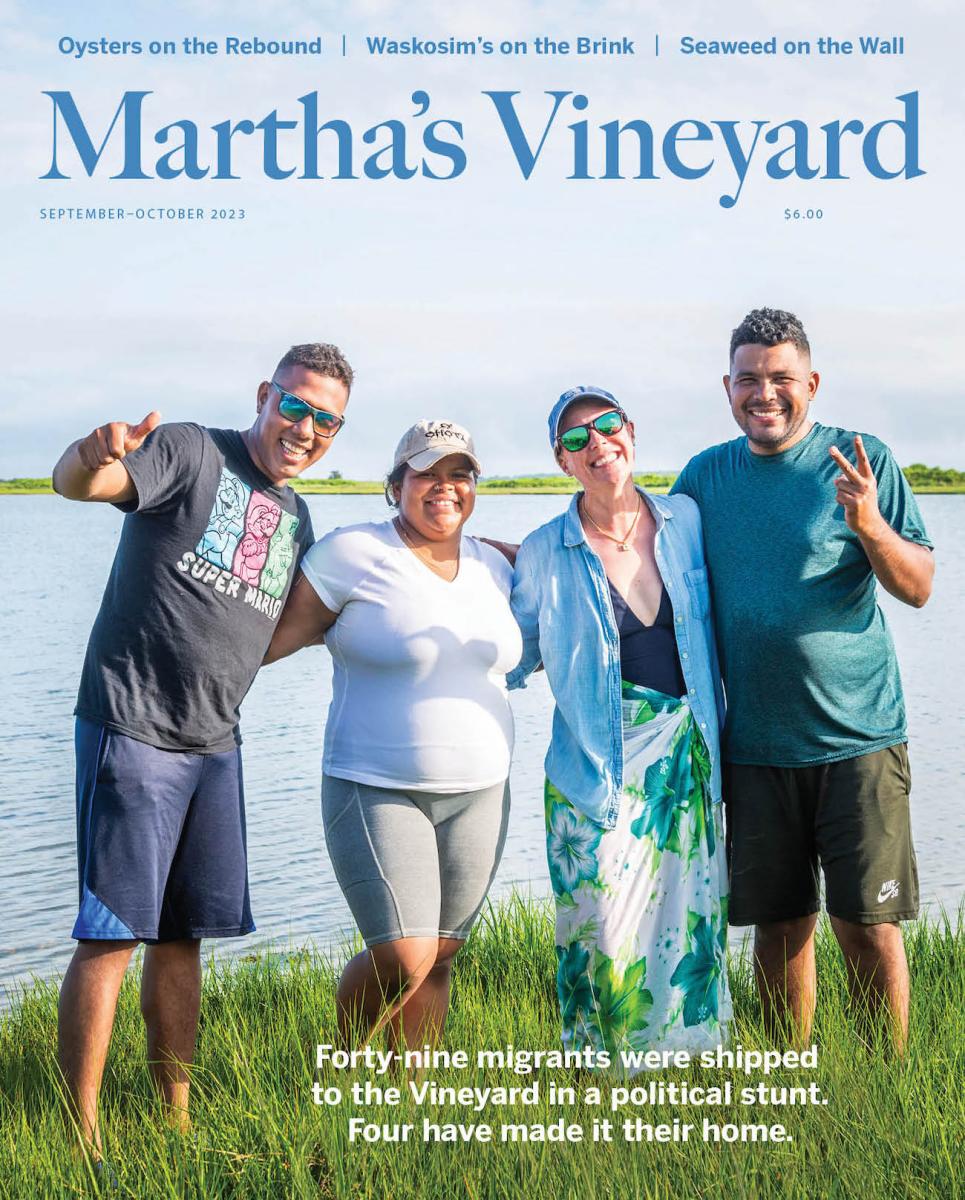

The tasks at hand and ahead are the work of all of us, and they are great. But as Brooke Kushwaha’s excellent story about the Island’s migrant response reminds us, the more assuring legacy of the Reverse Freedom Rides endures.