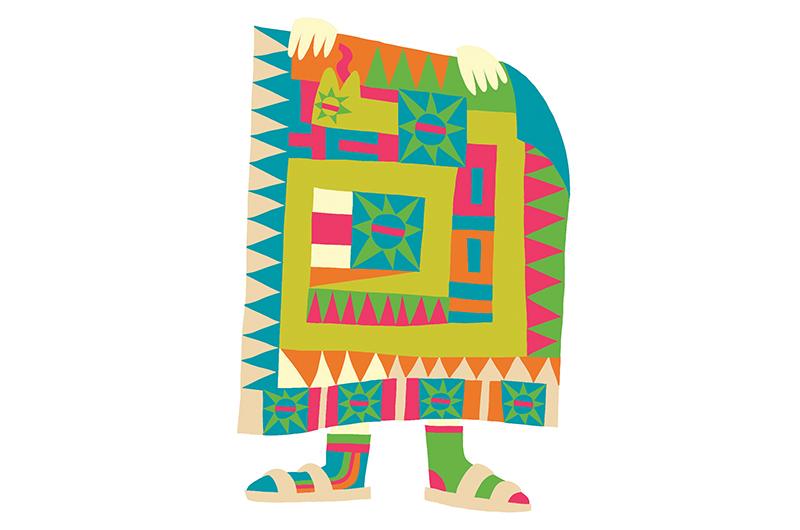

Picture a single, dark, unblinking eye. Around this eye, jagged black spears radiate, surrounded by a fuchsia orb. Then, expanding outward, a deep-red circle is bisected with purple snakes, bound by another ring of sharp, black points.

This isn’t a one-eyed monster or the Eye of Sauron. It’s the design of a quilt that artist Pamela Flam is creating at her home studio in Katama.

Some people may think of quilts as quaint patchwork blankets comprised of cheerful grids laid out over a bed at their grandmother’s house. But to Flam, they can be so much more. Like a painting, photograph, or sculpture, her quilts are works of art meant to inspire and engage.

Flam often enters her masterpieces into the annual Agricultural Fair in West Tisbury, where they’re hung from the hall’s rafters. She’s won several blue ribbons, but displaying them is essentially just the icing on the cake. The cake, in this metaphor, is the process. For her, the act of creating these quilts is profoundly soothing. “It’s the best drug in the world,” she said.

Flam grew up in New York City, raised by a mother with sewing skills. At ten years old, she tried out her mother’s sewing machine and things didn’t go to plan.

“She never really taught me how to use it, and I just started using it, and everything went kerfuffle,” Flam said. “So, she said I could never use it again.”

Undeterred, she bought her own sewing machine (a Singer treadle, for the machine wonks) at age eighteen. She later attended the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore and then transferred to the Parsons School of Design in New York City, studying fiber arts.

Quilting wasn’t top of mind until Flam had her first daughter, Anna. She decided to make her an Amish-style, one-color baby quilt. When she had her second daughter, Emily, she made another. Then, she had her third daughter, Molly, and she made a third. Flam has served on the boards of Featherstone Center for the Arts and Sail MV, but quilting has grown into a core part of her life and her identity, so much so that she’s considered the pain of losing it.

“If my eyesight starts to go, I could make some really weird quilts,” she laughed. “If I lost the use of my hands…yeah, that would be hard. Really hard.” She paused. “I’d have to start painting with a toothbrush in my mouth.”

Hopefully, neither will come to pass. For now, Flam starts her days in her studio in her house overlooking Crackatuxet Cove.

“I call it stitching meditation.”

Quilting, Flam said, is for young and old, men and women. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, British soldiers on bed rest made quilts from wool uniforms. In some prisons, programs exist to teach people to make quilts, which they then donate to children in foster care. Anyone anywhere can reap the rewards.

For those looking for a little tactile textile therapy, Flam said that quilting is dead simple.

For her own signature style, which she called “nontraditional improv,” a pattern is not needed. Sitting at a desk in her studio, she held up two scraps that she had nearby. “It’s just sewing one piece of fabric to another until you get to the size you want.”

Once you have your front, you lay it over batting, a fluffy material that can be made from cotton, wool, silk, or polyester. Then you sew a back on it. You can connect the three layers by “tying” your quilt, which means taking a needle and thread and tying knots all over, or you can do what Flam usually does and create a “running stitch” through the quilt in any design you like. This effect looks more like embroidery. In the very center of her quilted eye’s pupil, Flam used a red running stitch to write “See You.”

As for that eye quilt, it remains a work in progress. Flam has entered a quilt into the fair every year since 2008, but this year she may not finish in time. Although Flam said she would like to be quilting every minute, other parts of life can get in the way. Regardless, come August 21, Flam will go to the fair, enter the bustling Agricultural Hall, and look up to see the quilts made by other artists waving gently like flags.