Cristina Aragona and Gregg Jubin are no strangers to the Vineyard. Summer residents since 1991, for years they rented all around the Island, from Middle Road in Chilmark to Lambert’s Cove in West Tisbury to William Street in Vineyard Haven. But as their children got older, the family found themselves renting in Edgartown more, with the Jubin kids wanting to walk into town to get ice cream. Originally hailing from Old Town, a historic neighborhood in Alexandria, Virginia, they thought that Edgartown had a similar, old-character feel.

When the Davis Academy, at the corner of Davis Lane and School Street in Edgartown, went on the market in 2017, everything seemed to fall into place. It was the perfect location and the house emulated warmth – two things that Aragona emphasized in her search.

“What made us fall in love with it, besides the location, is that when you walked in the house, there was a lightness to [it],” she said.

That lightness was accompanied by a storied past, dating back to 1836 when David Davis rebuilt the private school after a fire destroyed the original early-1830s building that same year. Though the school itself only lasted a few more years, the first floor remained a public meeting and educational space known as Davis Hall. When Davis died, his extended family continued living in the home until it was sold to William B. Roberts, who was a pressman at the neighboring Vineyard Gazette. After just two years, the Roberts sold the property to the Perkins family, who owned it for twenty-three years. In October 1968, Sally and James “Scotty” Reston, the latter a longtime fixture at The New York Times, purchased the home after buying the Gazette six months prior. The family lived in the house for nearly fifty years.

Aragona and Jubin wanted to honor the history and design of the home as the previous owners had done, yet they also wanted to make it their own. The pair share a modern sensibility and a love of bold, colorful art.

To achieve their goal, they enlisted Connecticut-based architect Christopher Pagliaro, who is also Aragona’s cousin. Although Pagliaro was already dedicated to showcasing the juxtaposition between the traditional and modern, he soon found out just how much members of the community cared about the façade and history of this particular home.

Take the floor-to-ceiling window on the east-facing side of the home, a prominent feature of the Davis Academy that allows tourists and Island residents alike to peek into the main living space. Pagliaro said people would approach him while he was out to dinner, asking him not to change the windows. He and the family chose to respect their wishes.

“The beauty of this place is it has features that you frankly didn’t want to screw up in what you designed,” Jubin said. “Anything we did by way of architecture or design had to be complementary to the overall framework of this house.”

Because the home is in Edgartown’s historic district, not only did Pagliaro and the family want to appease their new neighbors; they also needed to heed the rules of the Edgartown Historic District Commission, which ensures that landmarks in the historic district adhere to the guidelines set by the commission. Any major changes and renovations to a building like the Davis Academy require an application process that details the planned renovations that must be approved by the commission.

Pagliaro and the historic district commission went back and forth many times during the two-year design and renovation process. In the end, some of their initial plans were rejected, a detached one-story, one-car garage was approved, and the exterior of the home remained mostly untouched. While it wasn’t what they were expecting, Pagliaro thrived in the challenging yet rewarding process of transforming the home.

“As an architect, what you…learn is that criticism is supposed to be productive, not negative,” he said. “It’s supposed to take you forward….

“They’re giving you a critique to open your eyes to opportunity…. Every place has its own unique situation, and then you take that, and you run with it.”

Today, the warmth of the house that Aragona fell in love with, as well as its new, modern sensibility, starts when you open the front door. There, a large dark yellow sculpture in the shape of a face greets family members and guests. Right behind it, a bright yellow circular staircase anchors the home. It is framed by columns inspired by those seen at a Buddhist temple.

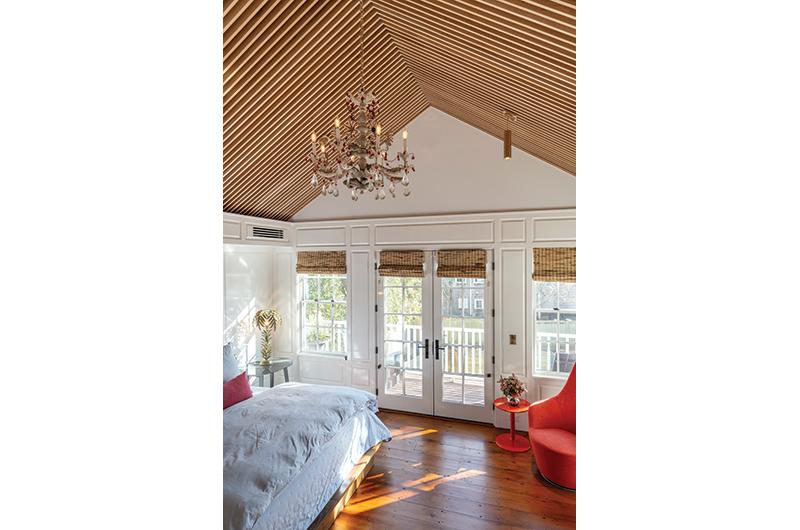

Aragona and Jubin’s bold design choices continue in the living room, which is outfitted with a black-and-white checkered floor, bright red chairs, and colorful chandeliers. Cozy nooks within the living space feature a more minimalist tone, including white chairs and cream-toned décor.

Because the owners are lovers of art, Pagliaro aimed to construct a floor plan that is reminiscent of an art gallery. This includes an open living room with a television that can be lowered so that it disappears into the floor, and a fireplace that can be rotated so that it faces a different direction when it’s not in use.

“We’re constantly changing what they’re purchasing and displaying...the goal was to keep it simple,” Pagliaro said. “Keep it open. Have the juxtaposition of the sleekness with the history.”

Most of the art pieces featured throughout the home are local, with Vineyard artists Lucy Dahl, Steve Lohman, and others represented. Winter Street Gallery in Edgartown and Granary Gallery in West Tisbury are two of Aragona’s favorites.

“Some people walk by and think it’s not very Edgartown in their opinion,” Pagliaro said. “But it is because [Aragona and Jubin] buy local art. It’s a town full of galleries, and you’re putting that into the residential community in terms of the visual of it. So, it is very Edgartown, because most of this stuff comes from the galleries.”

The homeowners and Pagliaro took care to retain some of the home’s original elements, such as the sinks in the kitchen and in the two-and-a-half bathrooms. The flooring throughout is also an homage to the history of the home, as most of it has been stripped and repurposed. A tub in one of the bathrooms is original but reglazed.

A goal of the renovation was to ensure that their family could live there for generations to come, so part of the additions included building another room in the attic that serves as a bedroom. The added attic space now brings the home’s total to four bedrooms with en suite bathrooms.

Originally, Pagliaro wanted to put a dormer in the attic to allow for a regular staircase and the extra room, but the historic district commission didn’t want a dormer facing School Street. As a workaround, Pagliaro suggested installing a spiral staircase, which would meet regulations and allow access to the space while providing ample room for headspace.

“From a practical design point of view, it was forced upon us because the only way we could get the fourth bedroom [was by incorporating the spiral staircase into the design],” Pagliaro said. “So, it became, how do you take that and make that the story?”

Another set of stairs leads to the basement, which is a harmonious mix of the past and present and was designed as a space to entertain guests. The original walls made of stone and cement are exposed, but rather than using them as the sole structural foundation, new steel beams were put in place. Now the walls simultaneously serve as décor and a part of the structural integrity of the home. This is a drastic change from before, when the basement was unfinished.

“We loved the basement walls in this house because they’re the living history that are exposed,” Pagliaro said. “Everything else is old wood hiding behind walls.”

Around the perimeter of the basement’s interior are bricks stacked on top of each other to represent the old beehive oven that may have been used for both heating and cooking in the original home. Spaced a few feet apart from each other on the brick are red tractor seats for guests to sit and mingle.

With a transformation on the inside to bring the house into the future, while honoring history on the outside, the Island character was considered with every decision Jubin and Aragona made. Two lanterns, for instance, frame the front door. While the lanterns are modern in design, they are lit by gas and made of copper and antique glass, once again bridging timelines and echoing the building’s history.

Jubin and Aragona know it’s an honor to be residents of a building that’s so distinctive to Edgartown and Martha’s Vineyard as a whole. With every update, they aimed to preserve the history written into the walls while still adding their own personal touch.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)