In the midst of dense, heavy fog atop calm waters outside New Bedford Harbor about thirty years ago, Buddy Vanderhoop piloted a boat home bearing sacred cargo.

Vanderhoop, a well-known charter fisherman and member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), was its repatriation officer then – the Tribe’s first ever. It was in this capacity that he had just met a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe to retrieve the skeletal remains of an Aquinnah Wampanoag family, a mother and her two young children, whose graves had been desecrated and their remains shipped to the mainland decades ago.

Now, they were coming home.

“I was going…to meet Slow Turtle from the Mashpee tribe, after he had gone up to the Peabody Museum [of Archaeology & Ethnology at Harvard University in Boston] and picked up a mother and two infant children that they had,” he said.

Vanderhoop was traveling outside the hurricane gates in the harbor when everything turned hazy. Then the haze turned to fog. “I was going about probably twenty-five or thirty miles an hour,” he said. All of a sudden, a strange feeling came over him so intensely that he pulled the throttle back. He didn’t know why. Seconds after he stopped the boat, a 600-foot ship cruised right in front of him.

“I would’ve smashed right into it,” he said.

Vanderhoop is certain of what saved him. “That was the mother of the two infants [who] wanted to get them safely back to their homeland, where they belonged.”

Once he had returned to the Vineyard, Vanderhoop, along with the chief of the Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe, the medicine man, and a few tribal members, gathered for a reburial ceremony. “[These remains] were sitting in a basement of a museum, and I don’t know how that ever made sense,” he said. “It was nice to bring a few people back, bury them back in their homeland where they belong.”

For Vanderhoop and his fellow tribal members, it was the latest effort in the long, nationwide battle to return the remains and artifacts of their ancestors to their homeland, where they could once again be given a proper burial. And yet for all the many homecomings that have been achieved, thousands of Native remains are still unburied, left to languish in more than a dozen museums, universities, and federal storage facilities across the country, including Harvard University, University of California–Berkeley, and the U.S. Department of the Interior.

According to a December 2023 report by ProPublica, an investigative journalism nonprofit, some 97,000 remains are still stored in such facilities, while another 18,800 have been repatriated by tribes throughout the United States.

Through several centuries of expropriation, the Indigenous populations of this country had little recourse to recover what was dug up and taken by archaeologists and treasure hunters. But in the latter half of the twentieth century, after much protest from the descendants of those buried, that began to change. As early as 1980, Massachusetts enacted state legislation to protect Indigenous graves and artifacts in certain instances. Then, in 1990, federal legislation made it illegal to despoil Indigenous graves and created a framework by which tribes could claim their ancestors.

With the new federal procedures in place, tribes across the country, including the Wampanoags, at last had the legal means to enact the homecomings for which they had long hoped. The passage of those laws was not the end of the story. Instead, it was the beginning of another chapter in a tireless fight for Native Americans to restore dignity to their ancestors. It is a fight that stretches back to the mythologized beginnings of the United States itself.

The trouble started four hundred years ago, with the first white settlers of what would become the state of Massachusetts, when Pilgrims unearthed Native burial sites shortly after landing ashore. Then came the treasure hunters, who, like the Pilgrims, soon learned that “Native people bury their dead with grave goods, which are often quite lucrative,” said David Silverman, a historian of early colonial New England. Silverman’s book Faith and Boundaries: Colonists, Christianity, and Community Among the Wampanoag Indians of Martha’s Vineyard, 1600–1871 (Cambridge University Press, 2007) focuses on the early history of relations between Europeans and Martha’s Vineyard Wampanoags. (The land then was called Noepe by the Wampanoag people, or “dry land amid waters.”)

Some of these early treasure hunters kept stolen items for display in their homes; others sold them privately for a profit. By the nineteenth century, private collectors and grave robbers – though they likely would have bristled at the name – were amassing huge assemblages that came to populate the oldest museum collections in the country. Those collections included arrowheads, ceramics, and craftworks, as well as tremendous quantities of Indigenous bones.

The problem was exacerbated over the century as archeology emerged as an academic discipline, fueled in the U.S. by the trendy eugenics movement. “The scale at which the archaeological profession collected Native bodies is staggering,” said Silverman, citing the statistic that, in the year 1900, the remains of dead Indigenous individuals in museums outnumbered the total living Native American population.

Some non-Native Martha’s Vineyard residents and visitors were enthusiastic participants of such practices. Federal records show that unearthing Wampanoag bones and shipping them off-Island goes back to 1870 at least, though the frequency at which artifacts and remains are still found during construction indicates it may have begun earlier.

Regardless of when it began, by the 1950s archeological digs had become commonplace on the Island. Archaeologist James Richardson, emeritus professor of anthropology at the University of Pittsburgh, participated in several. His first work in the field was as a teenaged volunteer on excavations led by Vineyard historian and amateur archaeologist Gale Huntington in the 1940s and ’50s. Later, in the ’60s, he participated in the Island excavations headed up by William Ritchie.

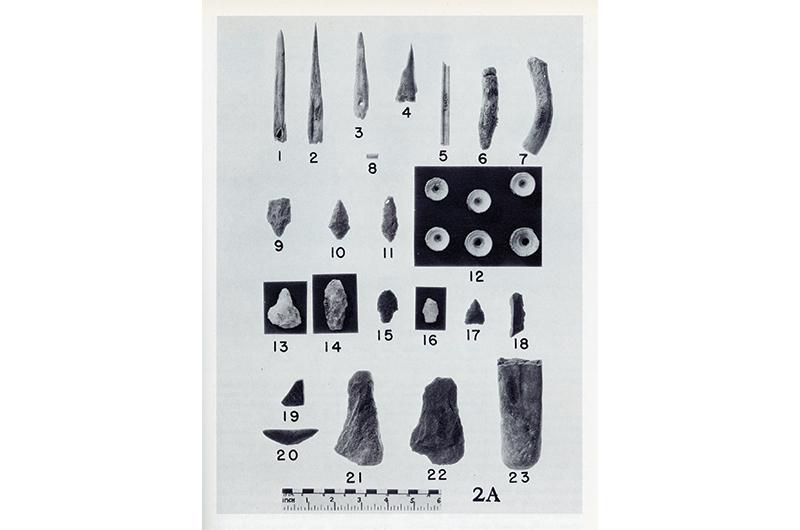

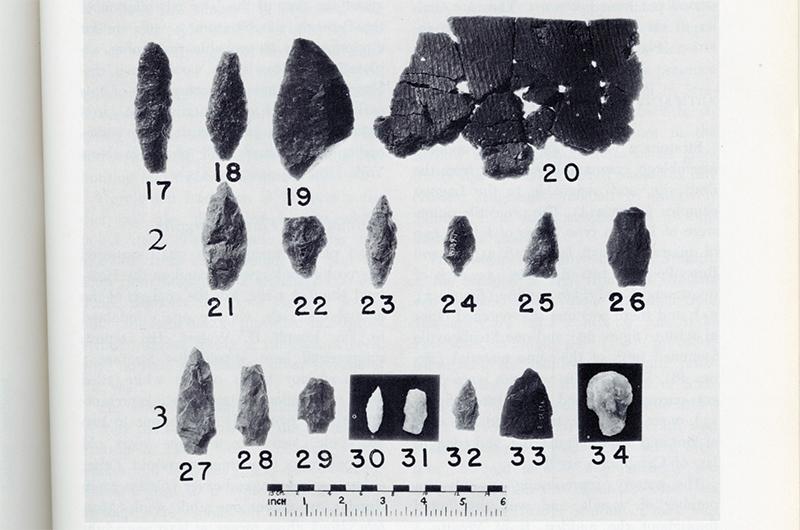

Ritchie’s 1969 book The Archaeology of Martha’s Vineyard: A Framework for the Prehistory of Southern New England (American Museum of Natural History, 1969) helped reshape archeology in the northeast and laid out a timeline of regional habitation that is still the foundation researchers use today. “With that book, he basically developed the whole sequence,” Richardson said. The digs, he explained, unearthed evidence of the highly diverse diet of seafood and wild game of the Indigenous people there.

Other digs on the Vineyard through the 1980s likewise revealed much about the society of the Wampanoag people in the years leading up to colonization. The relative lack of wampum beads found at various Island sites, for example, was thought to indicate a strategy of avoiding the attention of powerful political leaders, known as sachems, on the mainland. The presence of stone artifacts from as far away as Labrador indicated how deeply connected the Island was to distant exchange networks.

Such archeological excavations were often done without the permission or consult of the Tribe. As a result, an untold number of bodies and artifacts – including those unearthed by Ritchie – were shipped off to museums in New York, Boston,

and elsewhere without legal recourse.

Even as archaeologists became more scientific, consultations with Indigenous peoples remained intermittent in this era. The rift that they and looters left behind has yet to heal.

“Archaeologists did a great deal of damage to Native people by effectively collecting the remains of their loved ones,” said Silverman. “Suffice it to say, Native people have a fraught relationship with the archaeological profession.”

For a historian such as Silverman, the results of past studies form the bedrock of any understanding of the pre-contact period. He now uses them, as well as interviews with modern Native communities, to compare ancient artifacts with contemporary practices and still-existing oral traditions. Yet even while relying on the findings of centuries of archaeology, Silverman said, such findings cannot and should not be decoupled from their painful past.

“This is an act of white supremacy, let’s be clear what it is. They didn’t treat the remains of ‘respectable white people’ this way,” he said.

“If you talk to some old school archaeologists,” he continued, “they feel like they’ve been turned into these kinds of devils of colonialism, when they saw themselves as advancing knowledge of the human condition, and I think both things can actually be true at one time.”

This Eurocentric, anti-Indigenous worldview informed not only the practice of early academic archaeology, but also its conclusions. At the height of the era of eugenics, much ink was spilled, and many skulls phrenologically measured, in the interest of proving that contemporary Native Americans were not descended from those whose graves they were digging, which showed evidence of a sophisticated culture.

The Vineyard literati were well-acquainted with these trends, as evinced by a 1930s Vineyard Gazette article on the “racial characteristics” of the Wampanoag people, seeming to compliment the local Indigenous population while treading in old stereotypes about off-Island Natives. Historic accounts, the writer opined, are “not sufficient to explain why a barbarous people, pagan in their religion, warlike in nature, should cheerfully submit” to colonials, and that the “stoical, good-natured” character of Island Wampanoags “does not bear out the theories that the Vineyard Indians were of the same race as those of the mainland.” The writer went on to postulate that Island Natives were impacted by Viking contacts.

Such conclusions, perhaps, made it easier to justify continued excavations by denying their connection to modern Indigenous populations.

“The history of Europeans excavating these sites is they refuse to believe that Native people made them; they come up with all kinds of bizarre explanations,” Silverman said. “You got Vikings and strange Welsh priests and lost tribes of Israel who were supposed to be making these things instead of the most obvious conclusion, that it’s the Indigenous people.”

On-Island, doubts about the ancient-modern connection lingered long into the twentieth century, even as academic archaeologists had largely discounted them. A 1963 Gazette article describing “Indian remains” cast doubt on their true identity – “If indeed they were Indian,” it said.

As long as there have been colonists robbing graves, there have been Natives resisting them whenever they could.

In the earliest days of colonization, when Wampanoags and Europeans dealt with each other on more equal footing, the Indigenous population had power to manage these incidents. When the Wampanoag people found out about a group of Pilgrims digging Native graves in the seventeenth century, Silverman said, they mounted an attack on the Pilgrims before retreating at the sounds of musket shots.

In the proceeding years, though, on-Island and elsewhere, Indigenous society was rocked by disease, environmental devastation, and land expropriation.

On the Vineyard, Wampanoags were pushed off much of their ancestral lands, excluding the communities today recognized as Aquinnah and Chappaquiddick. An Aquinnah Wampanoag population that once reached around 3,000 individuals on-Island was by the late 1700s reduced to about 300. And so, with this decline in population and power, European speculation on the lives of “Ancient Indians” began, informed by amateurish observations of remains and artifacts.

On the Vineyard, the Indigenous population and the thrill of a treasure hunt became yet another tourist attraction.

“For many Island visitors,” the Gazette wrote in 1933, “the greatest charm lies in the search for Indian relics and prospecting about tribal places in search of traces of habitations, graves, and other signs of ancient Indian life.”

Non-Native residents and visitors were aware of the Tribe’s objections – just two years later the Gazette remarked on how “the sentiment of the Gay Head people is to prevent despoliation of the graves of their ancestors.” Nevertheless, the

problem continued, and even worsened, for the next half-century.

Throughout the twentieth century, the Gazette recorded a slew of artifacts and bones unearthed on the Vineyard, often during home construction or by amateur diggers. These remains and artifacts were typically shipped off-Island or kept by private collectors.

“We consider this the height of insult to the Indian people of the Island,” the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribal council wrote in a 1990 op-ed to the Gazette, following the looting of a gravesite that may have dated back 10,000 years. Remains were desecrated and historical value was destroyed in the process.

“Our ancestors have become the targets of amateur and professional archaeologists who hide behind scientific excuses to justify grave robbing,” they wrote.

It all reached a fever pitch in 1995, when a dark scene unfolded on Lucy Vincent Beach in Chilmark. According to The Boston Globe, a mob of treasure hunters learned of Native bones discovered in the eroded cliffs and descended upon the site.

“Dozens of trespassers trampled over the fragile, jagged cliffs and looted the grave,” the Globe wrote, “some bringing picks and shovels…to dig for bones and Native American artifacts buried

in the clay.”

The “nightmare on Lucy Vincent,” as it was called by the Gazette, triggered renewed efforts from the Tribe to put an end to three centuries of despoliation. This time, though, they had new legal tools at their disposal. The Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe received federal recognition in 1987. Then, in 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which made it illegal to traffic Indigenous remains and grave goods. It also established a procedure requiring institutions with federal funding to return such remains to tribal groups. The law has been modified and strengthened over the years, while the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’s own preexisting laws have bolstered those rights for the Wampanoag people.

“That changed a lot,” said Bettina Washington, the tribal historic preservation officer in Aquinnah.

Washington recalled her parents’ frustrations at the excavations in the days before Island Natives had any say. “I remember my dad talking. He goes, ‘They’re finding all kinds of stuff, and it’s in the back of their pickup trucks, and there’s nothing I can do about it,’” she recalled. “But then the unmarked burial law kicked in.”

As head of the Tribe’s historic preservation department, Washington works with a small group of people, monitoring sensitive development sites and consulting on active archaeological digs. Until recently, she also served as acting repatriation officer – a position within the historic preservation department. In that latter capacity, she was tasked with searching museum inventories for artifacts the Tribe may be able to claim.

“Our job is to make our job obsolete,” Washington said. In other words, the goal of the repatriation officer is to ensure that all the remains of their ancestors – and all the goods they were buried with – are returned and reinterred.

The work of the repatriation officer is now being continued by Jennifer Staples, who took over the position in November. “I am so honored to be joining the Aquinnah Wampanoag [historic preservation department]...to assist in the ongoing work of the restoration of our ancestors’s spirit,” Staples said.

And yet, as Staples might soon find out, progress in that role can be slow and intermittent. Following the passage of NAGPRA, Washington explained, museums with Indigenous remains were required to publish an inventory in the Federal Register, where tribes can review and claim them. Despite the law’s passage more than three decades ago, those inventories are still being updated, often a result of the lax attitude formerly taken toward such remains.

“Sometimes they say, ‘This is our complete inventory,’ and then, three or four years later: ‘We have to make an amendment to our inventory,’” she said.

In other instances, tribal members throughout the country have met with resistance when trying to repatriate items, with some suggesting that the museums were obfuscating, or dragging their heels, to hold onto valuable collections.

Harvard University, for instance, which has one of the largest collections of Native remains and artifacts in the country, recently came under fire for continuing to possess the remains of 5,600 Native Americans as of the start of 2024, according to ProPublica. Harvard did not respond to interview requests for this article, but has in other outlets reiterated its commitment

to repatriating all remains.

Around the same time, new regulations ordered that existing Native remains be removed from public displays across the country, including at prominent museums like the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Despite well-deserved frustrations with the pace of progress, it is, in fact, occurring. To date, ProPublica reports that the remains of twenty-eight individuals have been returned to Dukes County through the repatriation program. The Tribe has also claimed and reinterred hundreds of burial goods. More recently, the Tribe has begun to expand it scope.

While there are only two federally recognized tribes in the commonwealth (the Aquinnah and Mashpee Wampanoags), Washington said they have worked in collaboration with other unrecognized tribes across the state and region to return their ancestors as well. The Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe has helped to repatriate remains from as far away as Deerfield, Massachusetts; southern New Hampshire; and other tribes affiliated with the Wampanoag Confederation, for instance.

“We don’t know exactly what tribes these people came from,” she said. “We didn’t have state lines. And we had intermarriage.”

Cultural affiliation repatriation – a newer designation under NAGPRA that allows tribes to claim remains from related tribal groups, including ones where there are no longer living descendants – has made it easier to return remains whose specific affiliation is uncertain. However, said Washington, some institutions fought the provision or put off drafting inventories.

The Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe’s historic preservation department, headed by Washington, is also responsible for protecting gravesites and archaeological resources that could be disturbed during ever-proliferating construction and development on-Island.

“If you come down on human remains, you have to stop the work. And then there’s a process,” Washington said. Depending on the findings, archaeologists could be called in for an emergency survey, or the owners might be asked to make alterations to their construction plan. Most commonly, she said, landowners are asked to move their planned homes within the lot to avoid the site.

The Wampanoag Tribe of Chappaquiddick maintains its own historic preservation officer, Alexis Moreis. In a statement to Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, Moreis said that the Chappaquiddick tribe continues to advocate for all Island towns to adopt a zoning bylaw, similar to the one in Aquinnah, that would require archaeological land surveys of building sites in order to protect Wampanoag remains and objects of cultural patrimony.

“We urge private collectors and non-federally funded institutions to repatriate acquired Wampanoag artifacts (found or purchased) and allow our communities to heal from what has been stolen,” she wrote.

“The recent NAGPRA revisions place Tribes in the primary authority position in deciding where descendant remains, funerary objects, sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony are kept and how they are used.”

The creation of NAGPRA protections not only has helped to return sacred items to tribal members, it also has had huge implications for the world of academic archaeology and has reshaped what archeologists and archivists have been trained to do. “Serious advances in the archaeological record have almost dried up,” Silverman said of the northeast. “Now, archaeologists effectively get called in on an emergency basis, when someone’s putting in an in-ground pool, or there’s a construction project” where remains or artifacts are found.

On the Vineyard, as in much of New England, such emergency digs are conducted under the Public Archaeology Laboratory (PAL), a nonprofit institution.

“American archaeology in general is shifting away from a scientific and research-driven focus to a collaborative approach where descendant communities are involved in decision-making about cultural resources and what information should be collected,” PAL senior archaeologist Holly Herbster wrote in an email to Martha’s Vineyard Magazine. “We work from a position of respect for tribal knowledge and understand that historically archaeologists, including those who worked on Martha’s Vineyard, did not consult or collaborate with tribal members and that there is trust-building that still needs to happen.”

Since PAL was first hired to conduct an archaeological survey of Aquinnah tribal lands back in the early 1990s, Herbster said the group has conducted more than 150 of these studies across all the Island towns, with results typically not made public to prevent looting. Though their efforts are now also focused on preserving historic sites, and on making sure burials remain undisturbed, Herbster noted that the new paradigm has helped advance academic research as well.

“The study of the ancient and historic past on Martha’s Vineyard has benefited tremendously from the collaborative work between tribal members and archaeologists,” she said. “New England’s acidic soils destroy organic material quickly, so objects made of bone, wood, fiber, or plant matter…rarely survive on an archaeological site.

“Tribal knowledge about locations on the landscape, where people performed different activities, what types of plant and animal resources they used – these all help to fill in the missing pieces of the physical objects left behind,” she continued.

Silverman, too, said his own research has benefitted from consulting with Aquinnah Wampanoag tribal members. If some knowledge of the past remains buried beneath the Vineyard soil to protect the bones of ancient peoples, Silverman said, the trade-off is well worth it. “For my own two cents, I’d rather do without the knowledge and treat Native people with dignity.”

While the results of all these efforts could be counted by the individuals reinterred, artifacts returned, or even graves left undisturbed, the reverberations of those efforts cannot be so easily measured. On the porch of tribal councilor Kristina Hook’s Aquinnah home, just beyond the threshold, two gray archival boxes lay unopened. They would not have been out of place in Hook’s home, itself an archive of Island tribal history and ephemera, old papers and souvenirs and artifacts of Wampanoag life on and off the Island, but these are different.

Stooping down to take the lid off one of the boxes, she revealed their contents: rich tan shards of a steatite vessel, marbled beige and gray, unearthed years ago after millennia interred on the south shore of the Island.

Back when they were unbroken – before they were unburied – Hook believes these vessels once held objects. “Because it has been disturbed, some of my ancestors somewhere are not happy, so you don’t bring them into the house. You don’t bring them into anywhere where anybody goes to sleep at night,” Hook explained.

Back indoors, she sorted through more artifacts unearthed at the site – old arrowheads knapped to perfect symmetry, a stone chest plate piece smoothed and rounded and drilled with two holes, and the counterweight to an atlatl spear thrower that may have predated the invention of the bow and arrow, when woolly mammoth still walked the earth. These artifacts, removed during construction of a house in Chilmark, were kept in a private collection before a construction worker asked Hook to take them off his hands earlier this year.

“He said, ‘I’ve had these boxes for ten or twelve years, and I’ve tried to take special care of them. But I don’t feel that I should have these things anymore.’ And he asked me, ‘Would you take them?’ and he gifted me with them,” she said.

Hook is now consulting with the Tribe’s medicine man, Jason Baird, a traditional spiritual leader, about whether they should be reburied.

These kinds of more personal, individual returns – not the institutional repatriation mandated by NAGPRA – have become more common in recent years, Washington said, often resulting from younger Islanders finding items long kept by elder relatives and deciding that they should be returned.

“I think those attitudes are changing,” Washington said.

But, she cautioned, any artifacts that are found among old family belongings should not be handed over to individuals. Instead, she explained, they should be turned over to the tribal historic preservation department.

“We work with them,” she said. “We want to, if there are remains, to put them to rest.”

The sea change is not universal. To this day, Vanderhoop said he still sees treasure hunters out illegally digging for goods on the shores of Aquinnah. But hearts and minds are shifting. The attitudes of young archaeologists, too, are much different than they used to be, though attitudes toward the practice vary among tribal members. Vanderhoop looks back fondly on some of the old Ritchie digs, while Washington is largely ambivalent about their findings.

“If we’ve been doing archaeology this whole time, what have we learned? And not just what have we learned, but what have we learned to improve the descendants of these people?” she said. “I’m not really worried about what they were eating.”

For Hook, a connection to the Island’s Indigenous past was never dependent on academic study.

“Their spirits are still here,” she said. “When you’re in the woods, and you think you are lonely, you’re never alone. We’re surrounded by our ancestors and their energy has never left this place.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)