Every August when she arrives on the Vineyard, mixed-media collage artist Ekua Holmes makes a pilgrimage of sorts to lay flowers at the gravesite of Loïs Mailou Jones. “[She] is an inspiration and an icon for me,” Holmes explained of the famed artist. “Her talents, accomplishments, and determination are admirable. She experienced such in-your-face racism and sexism but persevered and won her place in the history of American art.

“We have a few things in common too,” she continued. Like Jones, Holmes is a Black woman who studied art in Boston. Both also worked for a time as designers – Jones in costume design, Holmes in graphic design – and are known for employing collage and bold color in their artwork.

“We were both influenced by the powerful art forms of West Africa,” she said. “And, of course, we love the Vineyard.”

Like Holmes’s own work, her studio in the Allston neighborhood of Boston is itself a collage, its shelves layered with binders, art supplies, and sculptures. Surrounded by her prolific output, she responds to questions immediately, with an open, ready smile, giving the impression that the concepts and philosophies she expresses have already been thought out. Which makes sense. Beginning when she was a very small child growing up in Roxbury, she was cognizant of the images around her. She was particularly drawn to photography: “Black people on church fans, pictures of Black families having Thanksgiving dinner. A friend of mine’s mom had a lithograph collection – I didn’t know they were lithographs at the time – of Black children,” she said. “That was different because most art depicted adults.”

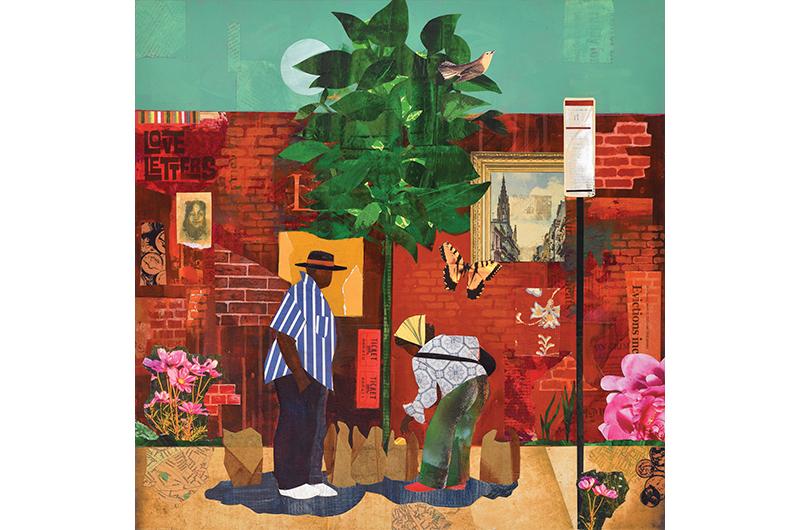

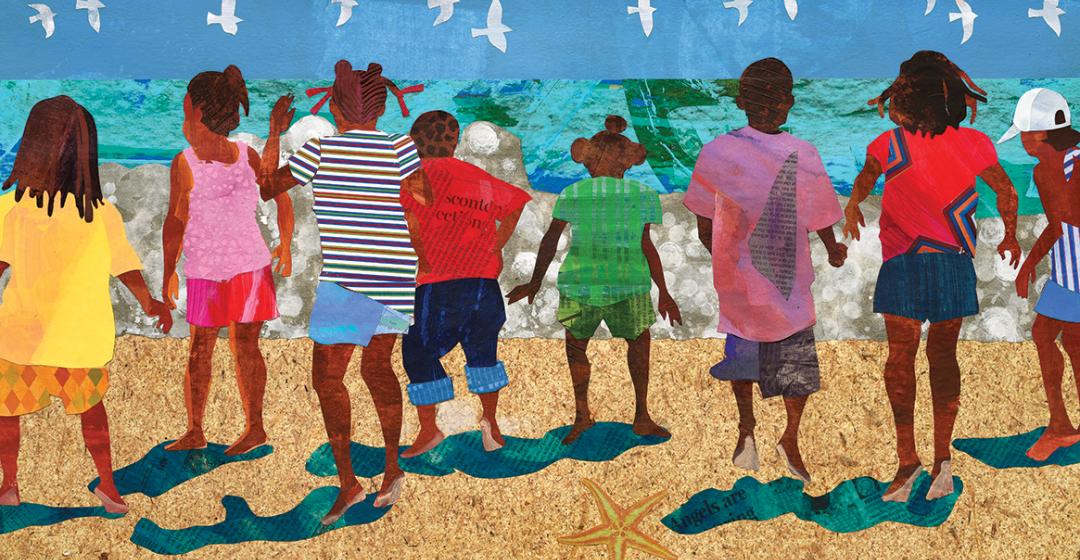

Today, Holmes’s work continues to feature and celebrate Black children – as well as adults – in keeping with her career-long commitment to advancing Black representation in art. In her vivid mixed-media scenes, made from meticulously layered cut and torn paper, children ride bikes against the backdrop of skyscrapers and traffic lights, wait at bus stops, help to hang clothes on a line, dive into a stack of books, or leap into the air in an act of freedom and self-expression. Each example features a strong sense of place, influenced by her childhood in the late ’50s and ’60s.

Holmes recalled fond memories from that time, such as visits to nearby Franklin Park: “Going there every Easter on the promenade, in flowered hats and white gloves. Family outings.” The scene is reminiscent of one of her own works, Remember Me, Easter Sunday, in which five boys don their finest suits, bow ties, and hats.

Life for Holmes and her contemporaries in Roxbury was not always easy, as the city infamously wrestled with longstanding scars of racial violence and segregation. Her family lived for a while on Dale Street, in a home she only remembers from “moving day,” not far from the residence of the future Malcolm X. The area has since been leveled by urban renewal. From there, they moved to another section of Roxbury, where Holmes remembered crying with other young students when white schoolteachers beat their male classmates’ hands with sticks.

“We had nightmares about [virulent anti-desegregationist] Louise Day Hicks,” who used to visit the school. “We knew she hated us,” she said. Holmes later transferred to an independent school in Cambridge, during an era when some Black parents in Roxbury and Dorchester sought more positive education options.

Yet for all the turbulence that young Holmes witnessed, the artist also saw – and continues to see and celebrate – her neighborhood as a muse and a magical place. “Roxbury is home to the legacies of icons like Mel King, Elma Lewis, Ruth Batson…and the Guscott brothers and many others who crafted our community,” she explained. “They laid the path for my generation to have better educations, broader experiences, and bigger dreams. Roxbury was a magical world where there was room for my imagination and love and support for my desire to be an artist.”

In the mid-1970s, Holmes held fast to that love of place when she enrolled at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt) in Boston. There, she pursued photography. “Most of my friends went to other cities,” she explained. “But I always found Roxbury and its stories compelling. People used to ask me, ‘Why are you always taking pictures of Black people?’ But nobody said anything to anybody else. You take pictures of what is around you,” she said.

After graduating, she experimented with a few photography jobs, taking photos for local newspapers, but didn’t particularly enjoy the work. Eventually, she transitioned to mixed media and worked as an independent curator.

Success didn’t arrive instantly, but it did come unexpectedly. “I curated other people’s work, because I wasn’t confident in my own work,” she said. “I was preparing an art show and an artist dropped out. I had this huge wall to fill. I put my own work up there, pieces that interacted with nature. Later, I noticed it had all sold out. Then I did it again, and that all sold out. That was twenty years ago.”

In the decades since, Holmes’s subject matter has expanded while still firmly staying rooted in themes of community, family, creativity, memory, and resilience. Starting in 2014, while continuing her own fine-art mixed-media work, she began illustrating children’s literature. Her first book, Voice of Freedom, Fannie Lou Hamer: Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement (Candlewick, 2015) by Carole Boston Weatherford, earned her a prestigious Caldecott Honor, a Robert F. Sibert Honor, a Horn Book award, and the Coretta Scott King John Steptoe award for New Talent. She has since illustrated ten more books and has been awarded two additional Coretta Scott King awards. In 2021, more than forty of her illustrations were presented at a one-person exhibition, “Paper Stories, Layered Dreams: The Art of Ekua Holmes,” at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

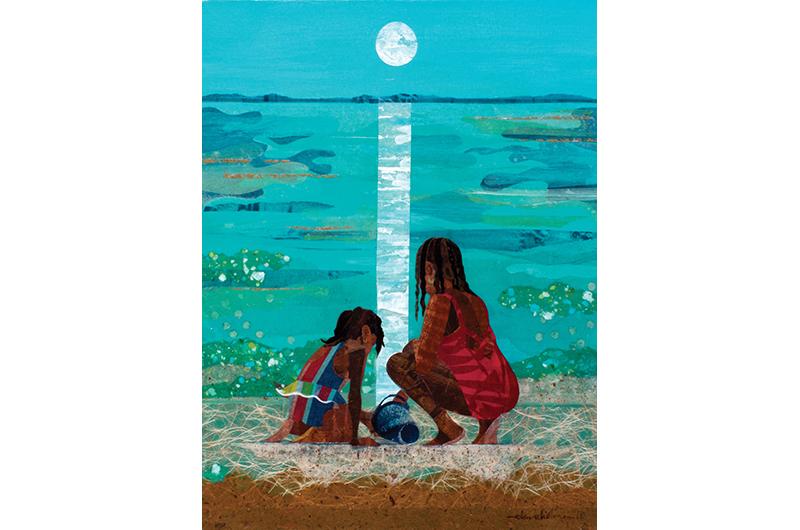

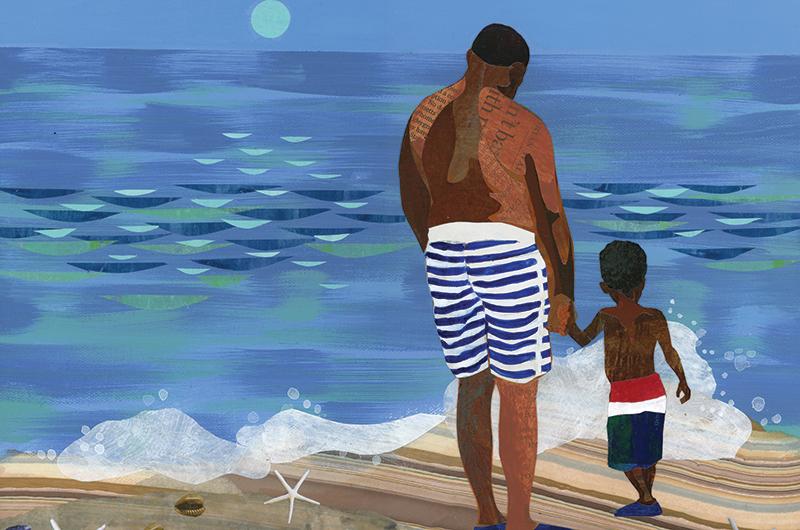

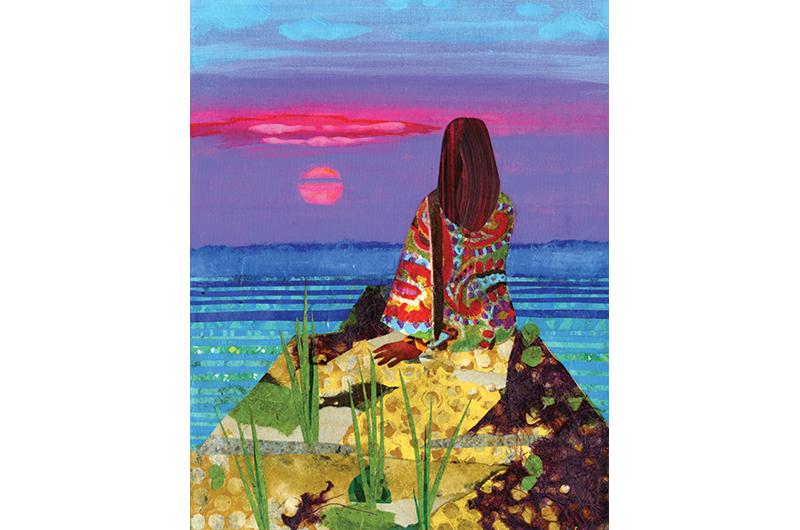

A couple of years before her first illustrated book was published, Holmes began exploring a new, ongoing series of seascapes. In them, saturated tones of blues, greens, purples, and yellows form a backdrop for beachgoers wading in the water, building sand castles, or pensively staring at the horizon. The start of the series coincided with her first trip to the Vineyard, in 2012. One of her previous graphic design clients had vacationed on the Island and talked glowingly about it, Holmes recalled. “Eventually, I decided to see for myself.”

The first two years she visited the Island, Holmes stayed with friends at the famed Shearer Cottage in Oak Bluffs, the oldest African American–owned inn on the Island. “I loved being close enough to walk to the bustle of Circuit Ave. but staying tucked away in the quiet of Morgan Avenue. I was so impressed with the history of the area. Seeing Dorothy West’s cottage and Adam Clayton Powell’s home among others inspired me,” she recalled.

As did the surrounding vistas. “The beauty of the various beaches and landscapes captured my imagination,” she explained. She began working on a few seascape pieces, which she presented to Zita Cousens, owner of the Cousen Rose Gallery in Oak Bluffs. Cousens was impressed by what she saw and agreed to represent Holmes on-Island.

Soon, it was Cousens’s patrons who were inspired. Holmes “transforms universal themes and everyday scenes onto the canvas for the viewer, who becomes drawn into the imagery,” she said. “[It] stimulates the imagination of each person who is fortunate to see her work.”

Given the artist’s predilection for celebrating one particular place, it’s tempting to assume that Holmes’s seascape series is inspired by one particular stretch of sand. The famed Inkwell Beach, after all, lies just a short walk from the Cousen Rose Gallery, where Holmes’s work will be on display from August 10 to August 21.

The Inkwell, then known simply as the Oak Bluffs town beach, welcomed Black visitors at a time when segregation was rampant. Its presence and continued popularity helped cement the Vineyard’s reputation as a racially tolerant summer resort. Today, it continues to serve as a cultural touchstone, its image preserved and celebrated in countless paintings and photographs.

And yet, Holmes has explained, her seascapes do not necessarily reflect one specific place, or that specific place. Instead, they are meant to convey a feeling.

“The world looks so different when it’s stripped down to what lies beneath,” she wrote on her website. “It looks different, it sounds different, it feels different. At the ocean, the surfaces under your feet yield to every step, the air is smooth – fragrant. The sounds are light. There are no walls to separate you from anything or anyone. All the tensions of city life are gradually washed away in the fresh air of the sea.”

“Initially, I was interested in oceanside rituals that go back to the beginning of humankind: baptism, family gatherings, renewal, swimming, and peaceful reflection,” Holmes said recently. To her, the Vineyard is both unique and part of a larger national narrative.

“I am generally here for one to two weeks,” she said of those annual visits. “I plan my trip around my opening reception and the fireworks. Then I’m off to explore: South Beach, State Beach, the Inkwell. I make the rounds.” Each has its own personality, she said: “The Inkwell is social; State Beach is turbulent, with big sky.”

In addition to visiting various beaches, Holmes spends time reading and cooking in her rental home, as well as thrifting, antiquing, and visiting art galleries. The Island is a welcoming place, she said. “As soon as we get on the ferry, we feel a weight removed. After a long year of work, we need that.”

Still, while Holmes doesn’t always base her seascapes on Island locales, she is well aware of its role in history and its importance.

“My work this season is an exploration of this historical movement, the remnants of it, and the aftermath. American Black-owned beaches and African American resorts are important cultural markers that are alive and thriving today,” she said. “Even if you have never been to Martha’s Vineyard and Oak Bluffs, as an African American, its history is a part of your story. It has been an engaging subject for renowned writers like Dorothy West and artists such as Loïs Mailou Jones.”

A few years ago, Holmes took a deep dive into the topic when she began illustrating a new book, Saving American Beach: The Biography of African American Environmentalist MaVynee Betsch by Heidi Tyline King (GP Putnam, 2021). The book explores the story of Abraham Lincoln Lewis, who bought a beach in Jim Crow–era Florida where Black families could go to enjoy themselves without being reminded they were second-class citizens. Following the desegregation of beaches, American Beach fell into disrepair.

“My research took me to other beachfront and resort enclaves of African Americans along the eastern coast, as well as California and Michigan,” she said. “The quest for ‘relaxation without humiliation’ – a phrase coined by Lewis – was pursued by professional and hardworking Black families at places like Chicken Bone Beach [in New Jersey]; Highland Beach, Maryland; Bruce’s Beach, California; and, of course, the Inkwell.”

The presence of other historically Black beach and resort enclaves “demonstrates we always sought places to take care of our spiritual selves. Safe places,” she said. Only a few such beaches remain, she said, one of which is the Inkwell.

Eventually, Holmes hopes to explore the other extant beaches. For now, though, she’s looking forward to her time on the Vineyard.

“Each year, coming to the Vineyard is like returning to an enduring and important friendship,” she said. “The ferry, the ocean, the beaches, the winding pathways welcome me. I love that collective moment of exhale that we all experience as the ferry leaves Woods Hole with its passengers.

“Martha’s Vineyard is a place that gladly receives every part of me – my love of history, good food, compelling art, unique and quaint homes, antiquing, walkability, serene weather, nature preserves, and so much more. It’s so close to Boston, but a world away.”

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)