In the summer of 1974, Charlie Blair saw a killer shark sink a boat, eat a man, and explode in Katama Bay.

And then he watched it happen all over, again and again – more than a dozen times in all, on the day director Steven Spielberg filmed the final showdown of the now-classic horror movie Jaws.

“I thought it was the greatest show on earth,” Blair recalled this spring. “They smashed the shark through the transom. It gobbled him up. The boat would sink.”

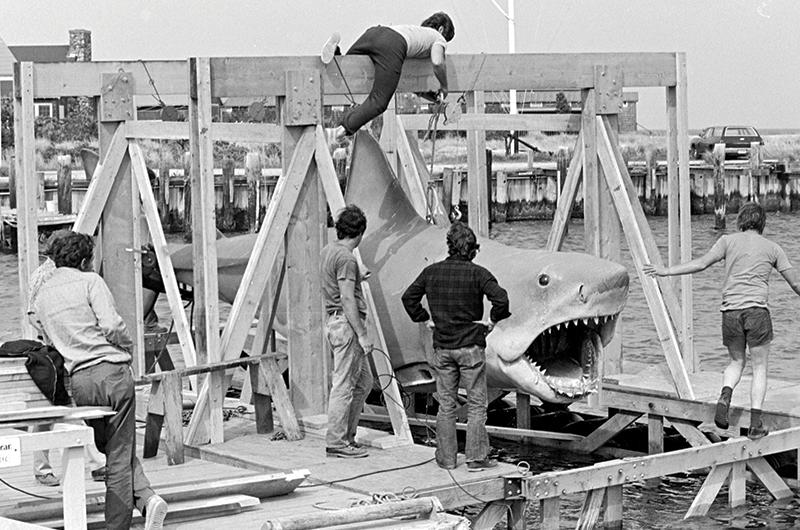

Blair, who was in charge of water transportation for the cast and crew, watched after each take as the “boat” – a platform replica of the fishing boat Orca – was refloated with air pumped into fifty-five-gallon drums beneath the deck. Another take would get underway with a fresh balsa-wood transom for the shark to destroy.

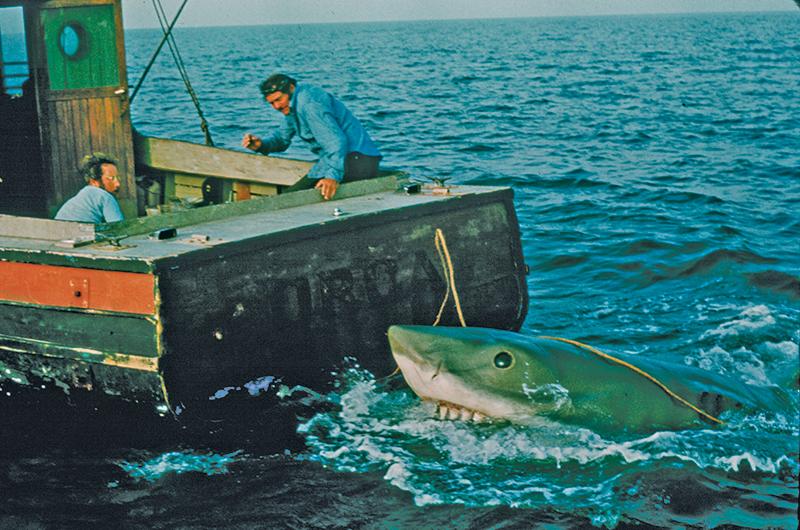

“To watch [actor] Robert Shaw’s double get eaten a few times was great too,” added Blair, who also was on hand when the shark – initially built in California and completed on the Island by veteran Hollywood mechanical effects man Robert Mattey – had its screen test in Edgartown waters earlier in the summer.

“They had a mock-up of the Orca. It’s all sugar glass and balsa wood. And they called for the shark. And those guys, Mattey’s crew, they brought that shark up to the surface and smashed it through the side of that boat.” The effect was spectacular, he said. “People were screaming and running. They’d never seen it before.”

That moment, Blair said, he knew that Jaws would be a success. “That first little tirade [the shark] had, that sold everybody. Everybody knew that they had a movie.”

Everybody turned out to be right, of course. Released in 1975, Jaws became an instant and enduring hit. Next year, for the movie’s fiftieth birthday, fans are expected to descend on the Island in force – during JawsFest in 2005, more than a thousand people attended a thirtieth-anniversary screening in Vineyard Haven’s Owen Park. For longtime Islanders like Blair, however, the true summer of Jaws was not the year of the film’s release but 1974, when the picture was being filmed here with scores of locals as extras, cast members, and production workers.

Intended as just a few weeks of cost-controlled shooting for a minor monster movie, the Universal Studios project famously ballooned into a months-long, budget-busting public ordeal that had twenty-seven-year-old Spielberg wondering if his second feature film would be his last. “I…could imagine never getting hired again,” he later told author Laurent Bouzereau in the book Spielberg: The First Ten Years (Insight Editions, 2023).

But while the famed director harbors no fond memories of his time on the Vineyard – he never left the Island during the shoot, he told Bouzereau, because he was afraid he wouldn’t come back – the summer of Jaws remains a touchstone for countless other Vineyarders and visitors who were here at the time.

“I saw so much [and] I have so much fun telling people, even now,” said Carol Fligor of Edgartown, whose four children were cast as extras.

Fligor herself was tapped by casting director Shari Rhodes for a job watching over all the youngsters on the set. She also used her Kodak movie camera to record eight-millimeter footage of the production, including a special performance by the mechanical shark to console her daughter Abby after a bumblebee sting.

“The cast and crew were always so nice to the children,” recalled Fligor, who filmed actor Richard Dreyfuss surrounded by youngsters between takes.

Even kids who didn’t get cast in Jaws were fascinated by the movie production and the mechanical shark that everyone called Bruce.

“We would ride our bikes down to the beaches, to the Jaws Bridge, all the time and follow them around. I don’t ever remember being chased away,” said Dolores Borza of Oak Bluffs, who was nine at the time and now runs Jaws tours as part of her Homegrown Tours business.

Summer resident Tot Balay of Edgartown and Virginia was eleven in 1974. “What was truly thrilling was that they kept Bruce, the mechanical shark, just down the street from us in the old boat yard,” Balay said. “I used to wait for them to take the shark out on their flatbed truck, covered in tarps – I waited on my bike and tried to follow it.”

Hard as it is to imagine fifty years later, it all might just as easily have been Nantucket’s adventure if not for a ferry cancellation when Universal production designer Joe Alves was scouting locations for the film in late 1973.

“I got on the Nantucket boat but it was so rough, we got halfway and the captain said, ‘We can’t make it all the way,’ so we turned around and came back [to Woods Hole],” Alves told the Vineyard Gazette last year. “I see the ferry to Martha’s Vineyard and I said, ‘Okay, it’s only eight miles away,’ and I exchanged my ticket.”

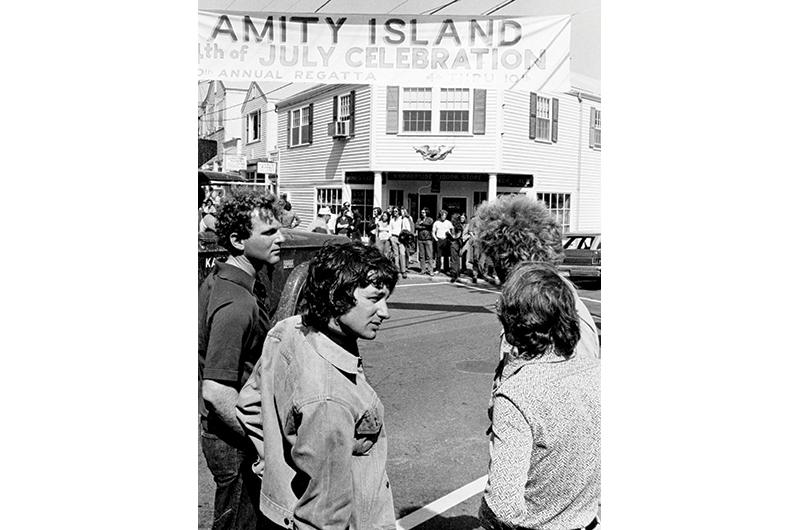

Based on the novel by seasonal Nantucket resident Peter Benchley, Jaws was set on fictional Amity Island off the Long Island coast. But Edgartown, Alves said, proved to be the perfect Amity: a tidy little town, ripe for unexpected on-screen mayhem, with plenty of open water nearby to make a truly convincing shark movie.

Many Islanders were wary at first, recalling the media invasion that had disrupted the Island less than five years earlier. After Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy’s deadly car accident at the Dike Bridge on Chappaquiddick in 1969 and during the subsequent trial, network news trucks the size of tractor-trailers had lumbered through the towns, stripping low-hanging branches from trees and blocking narrow intersections.

Once the news teams left, a macabre form of tourism took hold as obsessed off-Islanders streamed to view the scene of the crash, pestering locals for directions and chipping bits of wood from the fatal bridge for souvenirs.

But in early 1974, resistance to Jaws soon gave way to a compelling mix of star power and economics. Spielberg, whose first Universal film, The Sugarland Express, came out in March, was already acclaimed for his 1971 television movie Duel. His producers, David Brown and Richard Zanuck, had just a few months earlier delivered The Sting, a major hit starring Robert Shaw as the grim Depression-era crime boss grandly bamboozled by Paul Newman’s and Robert Redford’s con men. Shaw’s costars in Jaws were also Hollywood commodities: Roy Scheider played tough detectives in The French Connection (1971) and The Seven-Ups (1973) while Richard Dreyfuss had just starred in American Graffiti (1973), directed by the young George Lucas. Even Jaws itself was a hot property: written on commission for Doubleday and published in February 1974, Benchley’s novel was an immediate best-seller despite critical reviews.

Most motivating of all for Islanders, however, was the movie’s budget: a reported $3.5 million – a little over $22 million in 2024 currency – with much of it due to be spent on the Vineyard in the middle of a historic recession. (By the end of production, that budget ended up being closer to $8 million – almost $51 million in today’s currency.) “Suddenly there were a lot fewer turned-up noses and more turned-up palms,” wrote Edgartown photojournalist and

socialite Edith Blake in On Location….. on Martha’s Vineyard (Abe Books, 1975), her first-hand account of shadowing the Jaws production.

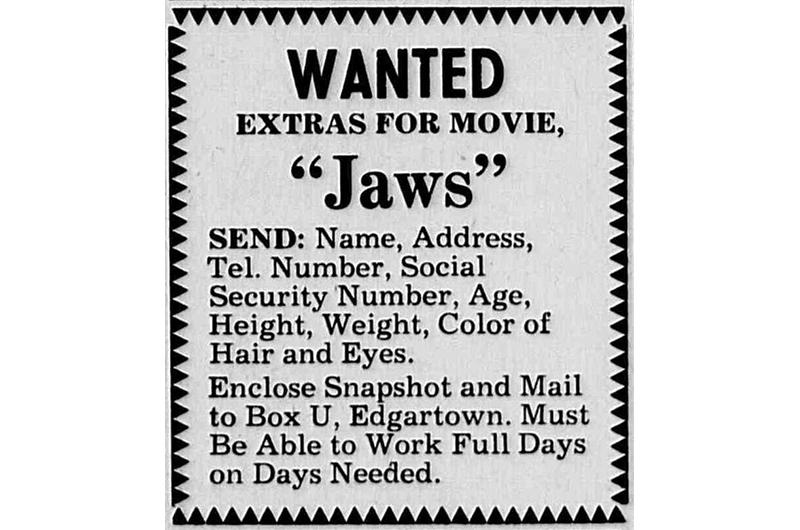

Hotel owner Robert Carroll was one of the first to benefit when Universal took over his empty, just-renovated Kelley House (now Faraway MV) in Edgartown in March of 1974. The filmmakers hosted a cocktail reception at the hotel for local officials and business owners, opened a production office on North Summer Street, issued a casting call, and started to hire.

Islanders of all ages dropped off Polaroid snapshots and some got the chance to audition, while the producers assured everyone involved that the whole shoot would be finished by June.

And for a while, it looked as if that’s what would happen.

Word quickly spread that extras could make $20 a day just to sit on the beach, and more than $120 if selected as “day players” for specific scenes. “With the money that we made as a family, we bought our 110 sailboat,” recalled Brad Fligor, the eldest of four Fligor children who were extras. Their father, Dick, appeared in one scene as well. Casting director Rhodes also picked influential locals for small but prominent roles, such as former Edgartown selectman Cyprien Dube as an Amity official and physician Robert Nevin as the medical examiner.

It wasn’t just would-be actors who cashed in. Island carpenters and painters became unaccountably busy when their regular clients called: Universal had brought only a skeleton construction crew to build the Orca fishing boat, beach cabanas, and other set pieces, so there was plenty of work to be had.

One of the busiest Islanders was marine mechanic Lynn Murphy of Menemsha, whose expertise helped keep the various shark devices afloat. “The sea-sled shark was just another scallop dredger as far as I was concerned,” Murphy told author Matt Taylor for the commemorative book Jaws: Memories from Martha’s Vineyard (Moonrise Media, 2011).

Murphy, who died in 2017, was one of Shaw’s role models for the character of Quint, alongside Island farmer and fisherman Craig Kingsbury, who played the small but pivotal role of Ben Gardner.

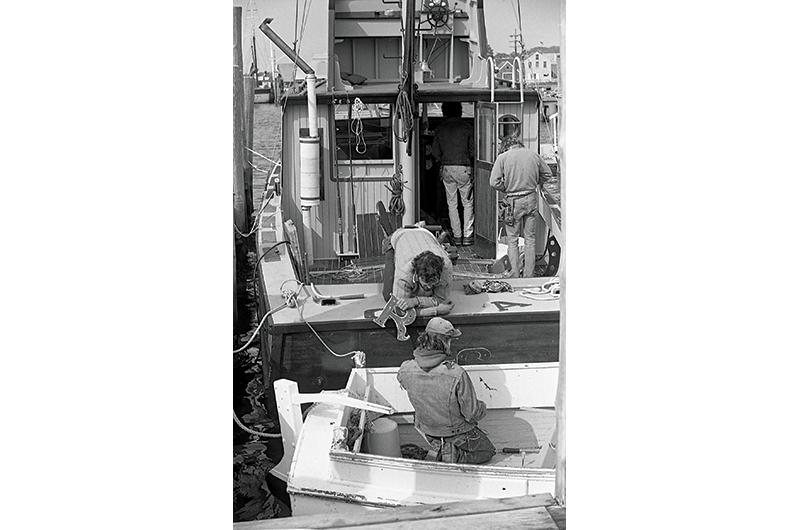

The production team assembled a working fleet of more than a dozen mismatched vessels, including the tug Whitefoot, the old City of Chappaquiddick ferry, and a barge called the S.S. Garage Sale, and hired Islanders to keep an eye on them. “My favorite job [was] as night security on the production barge, the S.S. Garage Sale,” said Kenny Ivory of Edgartown, whose first night on the job led to a short voyage with his bloodhound Moses when the barge dragged its anchor a mile out to sea. “[When] the day crew arrived...I never said anything about the drift,” Ivory said.

Even artists got in on the action. Painter Carla Hogendyk, who dated Alves during the production, plays the woman at an easel who sounds the alarm when the shark enters Sengekontacket Pond. Metal sculptor Travis Tuck began his acclaimed career in weathervanes with a $200 commission to create a shark vane for Quint’s shack, and CB Stark Jewelers still sells replicas of three original silver rings the prop department purchased for the shark’s first victim, whose severed arm is found on the beach.

At the Jaws production workshop on Fuller Street, a boat shed long since replaced by summer homes, anyone who brought in a T-shirt could have it silk-screened for free with the Jaws production logo. A pugnacious-looking shark head with its toothy mouth wide open and fins jutting from either side, the image conferred instant bragging rights, even for those who hadn’t managed to get in front of the camera.

The workshop also turned out Amity place signs for Edgartown landmarks and businesses: town hall, the bank, the market, and even the dry-goods store, which became Brickman’s of Amity Isle.

In June of 1974, Zanuck told the Gazette that Universal was spending $30,000 a day on Martha’s Vineyard – in today’s currency, that would be more than $190,000.

By that point Spielberg had been filming for more than a month, with locals appearing from the very first group shots. It had become clear from early on that the men from Universal Studios were not prepared for the Vineyard’s fickle spring weather – or for the corrosive nature of salt water on their shark machinery, which was meeting the sea for the first time.

They also had no idea how the ocean works, recalled Blair, who took over the production’s water transportation after its Teamsters union opted to stay on dry land. “Universal did not know what tide was. They did not know what current was. They did not know that you couldn’t change the wind direction. They knew absolutely nothing,” he said.

As Jaws fell further and further behind schedule, the Vineyard grew more crowded, with both summer residents and tourists increasingly attracted to the shoots taking place around the Island.

Tensions began to emerge. Neighbors of the Fuller Street workshop complained to police about late-night compressor noise, and dead sharks were deposited on the front steps of the production office in a form of smelly hate mail. Blair, meanwhile, was charged with keeping other boats out of the picture while Spielberg was shooting the Orca scenes.

“No one’s supposed to see a boat, which is impossible,” he said.

Getting skippers to change course for some movie director was also not possible, Blair said, so he did a little acting of his own.

“I didn’t even bother to ask them [to move]. I just sailed up to them and said, ‘Have a good day,’ and drove away,” he said.

Spielberg ultimately solved the problem of Edgartown’s busy waters by keeping all his camera shots below the horizon, said Blair, who ended the summer of 1974 with a weighty paycheck that enabled him, among other things, to build a boat and start his own sport-fishing business.

Today, some fifty summers on from the year the movie was made, Bruce the mechanical shark is still scaring up a few tourist dollars for the Island. These days, in his job as Edgartown harbor master, Blair regularly encounters Jaws enthusiasts visiting the Island to see filming locations such as the Orca’s last stand in Katama Bay, which can only be visited by water. “They go on scavenger hunts,”he said.

Aficionados also can take a land tour with Borza’s company, led by actual Jaws cast member Jeffrey Voorhees of Edgartown, who played the young shark victim Alex Kintner. Superfans can splurge on a private tour with Voorhees: one husband recently surprised his wife by booking one, Borza said.

“Jeff picked them up at the hotel and she just nearly fell to the floor,” she said. “They’re really 100 percent Jaws fans.”

There are Jaws themed T-shirts for sale, of course. And mugs, beach towels, and other assorted must-haves. No doubt there will be even more paraphernalia available next year, when the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in Vineyard Haven plans to stage a commemorative exhibit. Michael Dakin Cochrane, the great-grandson of a founder of Universal Studios, has also teased the idea of hosting a two-week long festival in Aquinnah, where select scenes were filmed. Cochrane hopes to display a replica of the famous Amity Island billboard in Lighthouse Circle, invite the Boston Pops to play music from Jaws, and hopefully re-screen the film on the day it premiered fifty years earlier. If plans come together, it will be a different way to view the film, in the shadow of where the billboard stood decades ago.

Then again, watching Jaws is always a different experience for Islanders. Many shots are filled with familiar faces and locations from a half-century ago, making the film a time machine for longtime residents. When Blair watches the movie, he can spot his father and stepmother as extras, along with friends and neighbors who have died over the years. Balay always looks for her late father, who is jibing his Laser in the background of the grisly Sengekontacket attack. And even Islanders who weren’t there crack up at the scene of Scheider’s character driving past the Gay Head Light and arriving promptly in Oak Bluffs.

Mostly, to them, it looks like an Island long, long ago and far, far away. Jaws came out before video stores were widespread, before DVRs were invented, before on-demand streaming was imagined. For fourteen summers after the film made its Island premiere, the best place audiences could watch the movie was at the former town hall theater in Edgartown, in the same building where part of it was filmed in 1974 – the pivotal meeting at which Shaw’s Quint makes

his first appearance.

That tradition ended when the theater became town office space in the 1990s. But the wall clock visible in that scene is still hanging in the meeting room downstairs – its hands unmoving, its face the only one in Jaws that’s exactly the same fifty years later.

This article has been updated to clarify Lynn Murphy's role on the film. He was not involved with security, as a previous version of this article stated.

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)