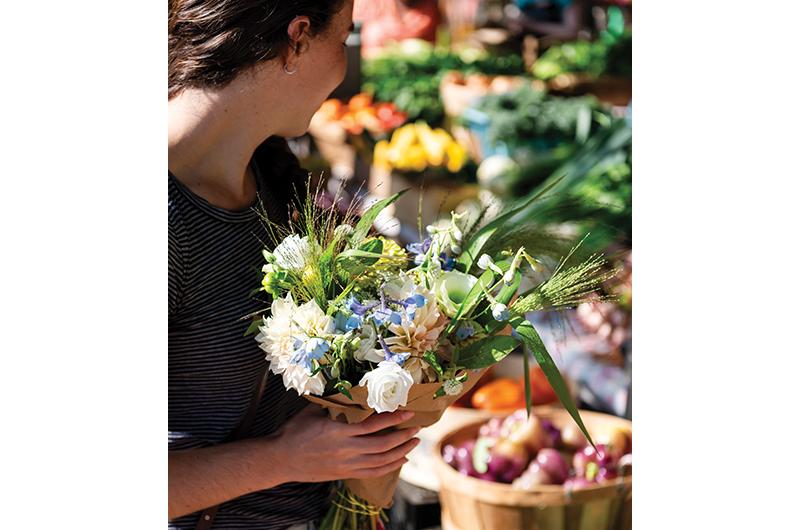

Every summer Saturday on the Vineyard, and most Wednesdays too, shoppers descend on the Agricultural Hall fairgrounds in West Tisbury. They come for coffee, sandwiches, and produce. They come for merriment and music. They come, as the motto says, “rain or shine since 1974,” for dairy, flowers, wool, and crafts. For baked goods, local honey, candy, and seafood.

It’s a tradition a half-century in the making – part vibrant social scene, part weekly bazaar.

It’s also a far cry from the market’s beginnings, when eleven humble vendors huddled with card tables and homegrown veggies under the porch at the market’s original and longtime location, the Grange Hall.

“It’s completely different than the beginning, when it was casual and you knew everybody,” recalled Susan “Soo” Whiting, one of the market’s first organizers, along with her cousin Prudy Whiting and friend Susan Silva.

“It took everybody to keep it going. A lot of perseverance and just showing up,” Prudy Whiting concurred.

Then again, the weekly in-season gathering was always intended to evolve.

From the outset, the West Tisbury Farmers’ Market has been an improvisation, an organization flexible enough to change with its participants. Its story is one of Island farmers figuring out how to make a living off the land – not for the first time and, likely, not for the last.

But for now, at least – fifty years into its run, and with no signs of slowing down – they have found a way to make it work.

Despite what the motto suggests, the West Tisbury Farmers’ Market has a history that goes back nearly a century, to the little-known 1935 Farmers’ Cooperative Market.

“The general opinion of the marketers was that it was a gratifying success from every point of view,” wrote the Vineyard Gazette at the start of that market’s second season.

“Of the early vegetables there was an abundance of beets, lettuce, spinach, and peas,” and “the shelves and counter displays of homemade jellies, jams, cakes, cookies, and many other toothsome goody were hunger-provoking indeed.” Woolen clothing, canned local seafood, fresh eggs, and paper craft flowers were also for sale.

Although contemporary reporting of the cooperative market is scant, later reports claim that it was started in response to the Great Depression, as a way to give locals another income stream by selling their garden and kitchen surplus. The market enjoyed moderate success but lasted until just 1941 – “a casualty of both the gas and sugar rationing that occurred during the second World War,” according to the Gazette.

It was only the latest in a series of booms and busts brought on by the outside world that had roiled the agrarian community.

Chief among them, perhaps, was the heyday of sheep farming, which lasted from colonial times until the 1800s. During that time, according to Clyde MacKenzie Jr.’s survey of Vineyard livestock history in the August 1997 edition of The Dukes County Intelligencer, the Island landscape was dominated by sheep pasture. But by the turn of the century, cheap wool on the global market had begun to undercut Island prices. The decline of the whaling industry also meant less demand for local textiles. The industry soon went belly-up.

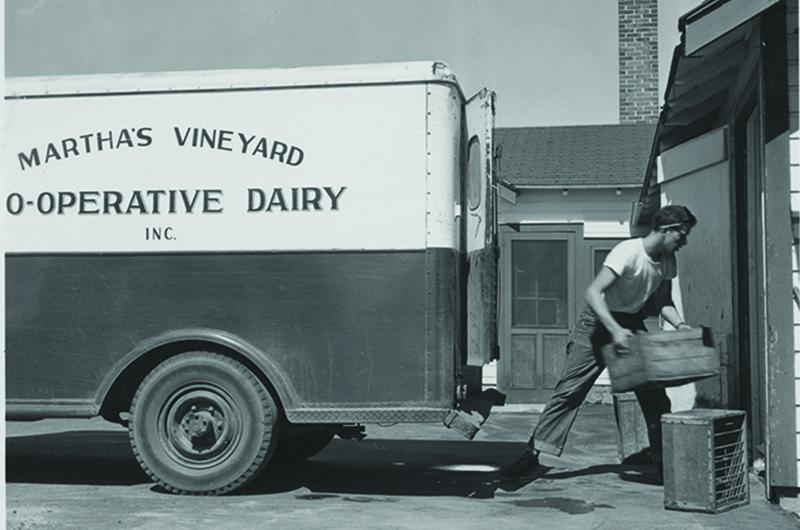

The next century brought the heyday of Island dairying, when milk and ice cream deliveries fed a burgeoning summer population. At its height in 1951, the Island’s Co-Operative Dairy sold 757,000 quarts of milk. And yet the preponderance of cattle could not last, as supermarkets began to import cheap mainland dairy. In 1963, the cooperative folded and local dairy collapsed.

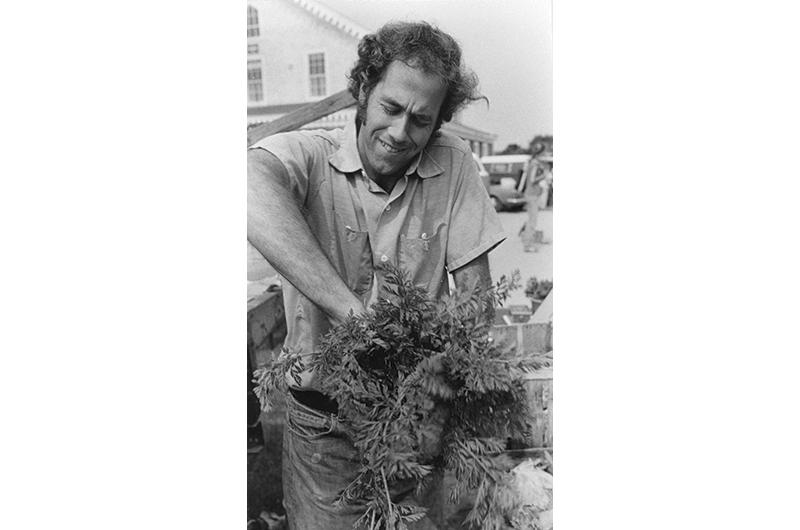

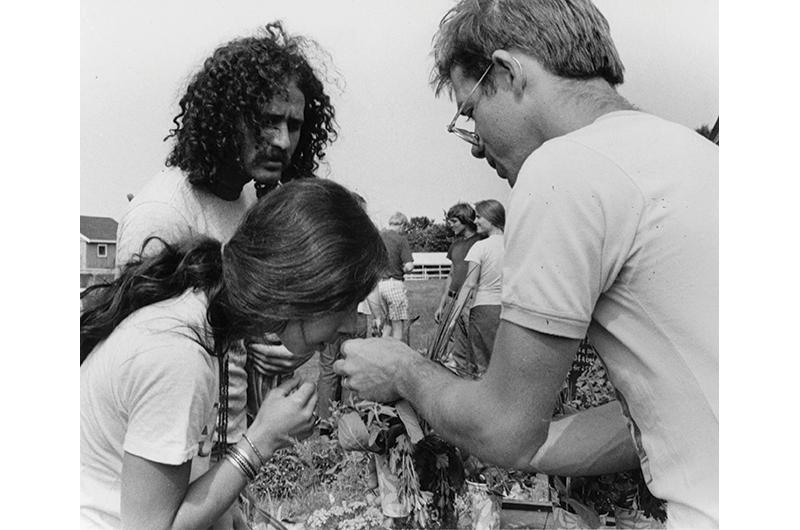

The downturns cast long shadows on the future of local farming. By the time the 1970s arrived and a group of old school Island farmers and “hippie back-to-landers” sought to resurrect a farmers’ market, they knew that if Island agriculture were to remain an economic engine, a new breed of growers would have to find another way to make their work profitable and prevent their products from being undercut by mainland competition.

They would have to find a way to reliably (and cheaply) get their harvest in front of buyers.

The revolution in local produce was about to begin.

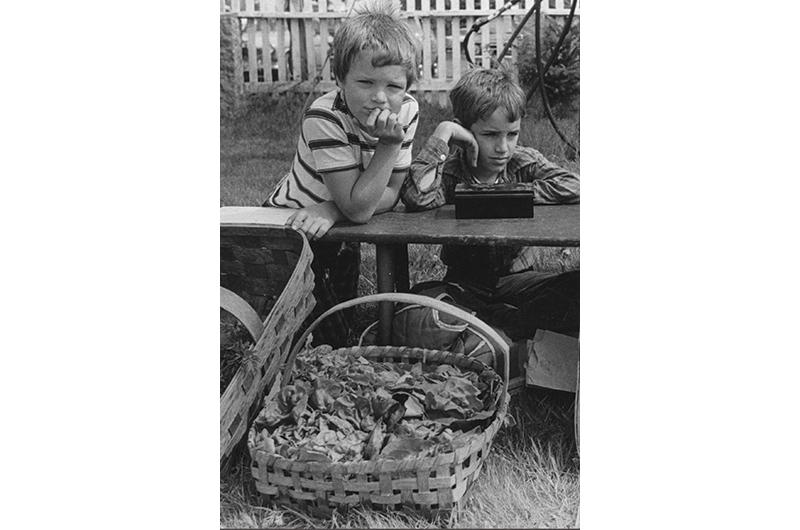

When it was revived in 1974, the movers-and-shakers behind the West Tisbury Farmers’ Market didn’t envision the commercial powerhouse it would become. It began, rather, as a small community of home growers and small-time farmers looking to broaden their reach. “We all had gardens at that point, and we all had more than we can eat,” recalled Prudy.

The idea, inspired by Soo’s work with the Vineyard Conservation Society, was to create a place for local growers to sell their surplus, giving summer visitors and Islanders access

to high-quality produce, and farmers a source of extra income.

“Because of the high price of produce in the stores, there has been a resurgence of interest in vegetable gardening,” the Gazette wrote on the occasion of the market’s revival. In another article, it waxed on about the “young onions as lustrous as pearls, crisply curling green lettuce in shades of green, chartreuse and rose, and golden oatmeal bread” on offer.

The writer also quoted Soo’s pricing advice to marketeers: “Remember that fresh produce is a luxury item…and price your things accordingly.”

As with any new venture, there were growing pains. “We had a dog that lived next door to the [Grange Hall]. His name was Bear. He was very territorial,” Soo said. During market days, Bear would often get into fights with other visiting canines. “Well, one day Bear came over and got into one heck of a fight, and I ended up taking the bucket of water that had my lettuce and dumping it over the dogs, breaking up the fight,” she said, chuckling along with Prudy.

Dog fights aside, the marketeers had a larger issue to deal with: the harsh economic realities of a modern farmer.

“For us, it was an experiment that failed,” said Tom Hodgson, who, with his ex-wife, Pam Thomas, sold vegetables and flowers for the first five years.

“There’s a stereotype that farming is something stupid people do,” he said, “and that is not at all true, so not true. It requires superb organization skills and requires phenomenal amounts of labor.”

Hodgson was part of that optimistic freshman class of marketeers, but enthusiasm didn’t always amount to success. “We’d gross between forty and 120 bucks a week, which is barely coffee money in this day,” he said. Between the time it took to set up and run their table, and the work that went into growing, it wasn’t a great hourly rate.

“Once the kids came along, we succumbed to the crumby economics of farming,” said Hodgson, who returned to house and then sign painting.

While the market proved unsuccessful for some, the low barrier to entry – the price for a vendor spot was one dollar – made it a launching pad for others, particularly those who were just starting out and able to make a significant time commitment. Over the years that list has included Whippoorwill, Ghost Island, and North Tabor Farms, as well as one veritable Island farming institution: Morning Glory Farm.

Jim Athearn, who founded the Edgartown farm with his wife, Debbie, wasn’t at the market the first year. In 1974 his only crop was hay, unappetizing to humans. But by the next year, he borrowed his father’s land on Music Street in West Tisbury to plant half an acre of sweet corn. “I took that over to market to sell, quickly finding out that it was overtaken with worms,” he recalled.

Despite the crop failure, Athearn found inspiration in other vendors and their range of produce. “I thought, ‘Well, goodness, I shouldn’t just bring corn. I should bring lettuce and carrots,’” he said. “So the next year, we got more honest and planted a larger variety of crops, and we were quite pleased with the result. And we’ve been going ever since.”

As have the crowds. “We’d get all worried about competition,” Hodgson said, “but what actually happened was that many more people learned what fresh vegetables were like. And instead of being less business for everyone, it was more business.”

In the words of Prudy, “People just kept coming, and coming, and coming.”

As the market shifted from a vernacular gathering to a burgeoning commercial institution, a once-simple decision became ever-more complex.

In the first years, Prudy recalled one of the rules being: “You could only sell what you grew.” (There were a few exceptions, including “baked and preserved goods and eggs” that were “Island reared.”) The rule was set forth by the Agricultural Society, then-owners of the Grange Hall.

Over time, regulations eased, making way for prepared food vendors. But the permissiveness begged the question: how many non-farmers could join before it would no longer be a farmers’ market? By the 1990s, a committee of vendors and organizers came up with an answer: no more than one-third of vendors could be non-farmers. It is a proportion the market follows to this day.

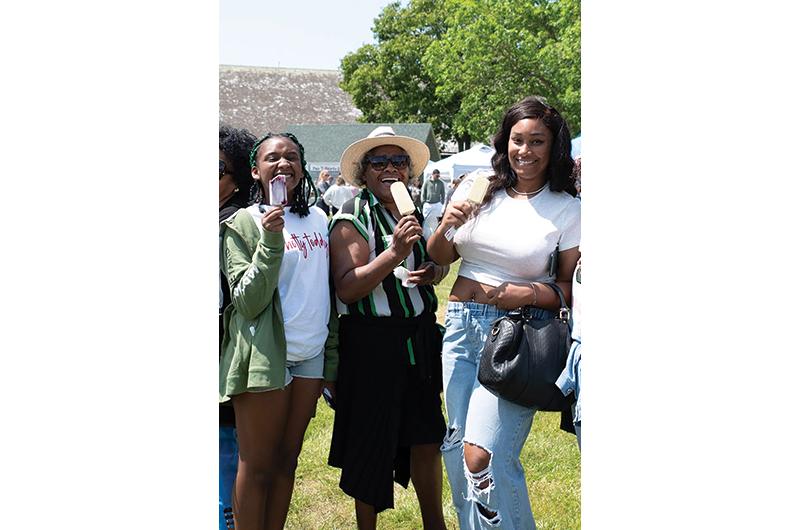

The opening of the market to non-growers proved to be a recipe for success, with prepared foods, from jams to egg rolls to ice cream pops, attracting more than the typical produce-shopper crowd.

It was “an event to be seen at,” said Linda Alley of New Lane Sundries, who first perused the market in 1987 and joined the next year.

Her fellow jam maker, Ethel Sherman, opined on market society and the fashion statements she saw there in her 2003 self-published book, West Tisbury Farmers’ Market: Behind the Scenes. Shoppers might show up wearing “a long frilly gown or a charming large, brimmed hat adorned with a cabbage rose,” she wrote.

In 2011, the Gazette likewise commented on the scene, dubbing the market a “Social Circuit for the Soil Set.”

The growth of the market brought a measure of financial security to its participants, many of whom made all or a good portion of their income there. It also brought hundreds of cars to the center of town.

“It was talked about everywhere. I mean, people were backed up to Deep Bottom Road,” recalled Alley.

By 2017, the traffic had gotten so bad that it inspired her to create a new recipe: a strawberry-blackberry-blueberry-raspberry mélange she dubbed “West Tisbury Traffic Jam.” It has since become her best-selling item.

While the increased traffic did little to deter shoppers, it did inspire plenty of consternation. As early as 1996, West Tisbury select board member John Alley began raising concerns to market organizers. Even so, it would take another twenty years, a global pandemic, and a forced location change to find a solution that worked.

In many ways the fairgrounds of the Agricultural Hall – acquired by the Agricultural Society in 1993, and the new home for the market – is a natural venue for the weekly event, especially given its frequent displays of merriment, music, and crowds. Some people, in fact, had been advocating for moving the market from the Grange Hall to the Ag Hall for years.

But when the move finally came, it had little to do with traffic or any association with the Agricultural Society. The pandemic had forced the hand of market organizers: social distancing mandates were in effect, and the Grange Hall didn’t have enough space. If the market didn’t move, it would close.

“We have fifty vendors who rely on us, several of them exclusively for their income,” then-market co-manager Collins Heavener told the Gazette in the summer of 2020. He and his fellow manager, Olivia Rabbitt, orchestrated a last-minute change of venue to the fairgrounds.

That summer, pandemic refugees, visitors, and Islanders seeking a safer open-air activity came in droves to visit newly spread-out vendors. From June to mid-July, more than 11,000 people attended – a likely record, organizers said, although head counts had never been conducted before.

The new location was largely well received, even by some of the most obstinate Grange Hall purists. “I was one of the ones who was wanting to never go over to the Ag Hall,” said Alley. “I love it. I can’t believe I’m saying it, but I love it.”

Still, not everyone was as quick to hop on board.

“That first summer was kind of crazy,” recalled Chris Lyons, facilities and maintenance manager at the fairgrounds, who became a frequent sight managing traffic atop his four-wheeler after the move.

Another challenge came in 2022, when the market went before the town zoning board to get approval to make the new location permanent, following good reviews from the first two years. “There was some kickback, some resistance from the town about having it here,” Lyons said.

Certain officials used the opportunity to question whether the market had strayed from its original mission, allowing in too many non-farmers. They pointed to the newly added food trucks, the loss of longtime vendors who decided not to relocate, and the rise of so-called “value-added” farm products – everything from soap to herbal tinctures to knitted sweaters. Though always a part of the market, such items have recently come to the fore as a way to boost a farmer’s bottom line.

Even some market stalwarts acknowledged the shift. “It sure has become the weekend destination since we’ve gone over to the Ag Hall,” Alley said.

Ethan Buchanan-Valenti, the current manager of the market, agreed. When he first came to the market as a Morning Glory worker in 2004, he immediately noticed the ambiance.

“At the Grange Hall, it was tight, cramped, super crowded, but a still really fun, cool vibe,” he said. “[Today] it has a totally different vibe and feel to it. It’s definitely changed, big time.” At the same time, he said, “it still feels like the same old market.”

Buchanan-Valenti’s appointment as manager last year represented its own sea-change. He is perhaps the only manager in the market’s history who doesn’t double as a vendor, a signal of the growing magnitude of the job.

“It just keeps snowballing,” he said. “There was a boom in the pandemic, because people were starving for local food.”

Then again, as many of the vendors know too well, booms, busts, surges, and resurgences of popularity in both the market and the Island farming community at large are nothing new. For five decades, and for centuries before, the farmers have never left, even as change has challenged old customs.

“I have to chuckle, because it seems like every few years there is a resurgence in farming,” Athearn said.

Whatever the next fifty years may bring, the trick for farmers will be to keep adapting, even while rooted in the past.

Emily Fischer, a vendor and market committee member, has done just that. The daughter of a multi-generation farming family, she first came to the market as a baby, propped up on her parents’ truck behind their stand, and served a stint at the Kitchen Porch prepared-food booth as a teenager. Today, she sells goat-milk soap, made on her family’s Flat Point Farm in West Tisbury.

“It’s a gamble every year,” she said of traditional produce farming. “You might plant something and it doesn’t go right, and then that’s it.”

Plus, Fischer added, vegetables bring a slim margin.

Today, her stand sits among flower farmers, Island Alpaca Company hats, a rotating selection of prepared goods, a sampling of food trucks, and plenty of card tables stacked high with lettuces, tomatoes, herbs, and squash.

The variety is what keeps the market such a vibrant retail space, she said. “Otherwise, you could just get what you want from Cronig’s.

“The fact that people come to the market and support farmers,” she said, “it doesn’t go unnoticed.”