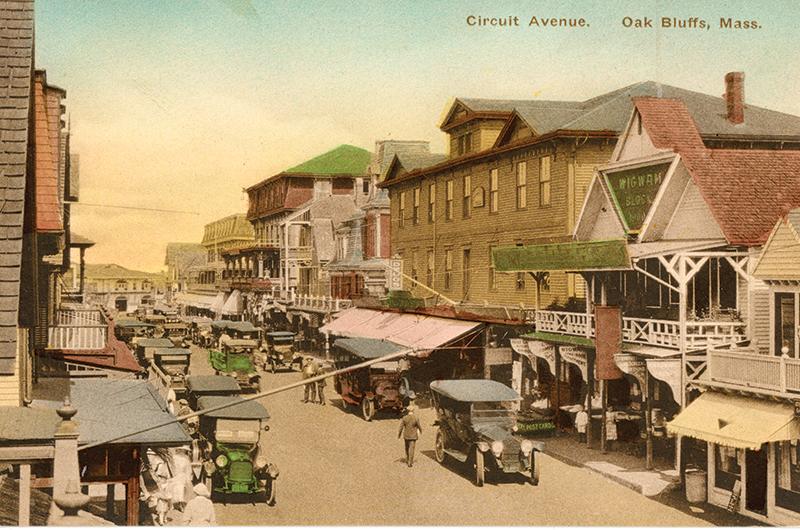

Scott Slarsky keeps a collection of vintage Oak Bluffs postcards on hand. The images date from the late-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, a time of great change in the seaside town. The community at the Methodist Camp Ground was booming, with more and more of the original tent platforms being converted into the permanent gingerbread cottages that are so famous today. Nearby, the newly formed Oak Bluffs Land and Wharf Company had subdivided a seventy-five-acre parcel for development. At the waterfront, a massive 125-room hotel called the Sea View was erected. President Ulysses S. Grant arrived for a vacation. The Flying Horses Carousel opened. It was the town’s first golden age.

Slarsky, who is an Oak Bluffs resident and an architect with the Boston Planning & Development Agency, doesn’t keep the cards on hand to remind him of the past. Instead, he sees them as a template for the future. He pointed to one of the postcards depicting a vibrant, pedestrian-filled Circuit Avenue. Multi-story buildings lined both sides of the street. Some of the buildings housed grand hotels, such as the Pawnee House Hotel and the Island House. Others were home to thriving businesses with ample space for living quarters above.

Over time, many of these buildings were torn down and replaced with the squat one- and two-story structures we see today. The move mirrored similar actions taken throughout the country, as the rise of the automobile allowed vacationers to move away from the Island’s busy towns to more rural settings where they built private summer homes.

Land was cheap and readily available then for both seasonal and year-round building. By the mid-1900s, the Vineyard was full of farms that had gone broke or gone to seed. But times changed and so did real estate prices – more rapidly on the Island than off it. In 2023, the median household price on the Vineyard was $1.5 million, more than twice the state-wide median price of $579,900 and more than three times the national median of $417,700. At press time, the cheapest single-family home for sale on the Island was $699,000. It was just 370 square feet.

The effect of surging prices and a competitive real estate market is today old news. Employers – from grocery stores to schools to hospitals – can’t find enough space to house their workers. Families, some of whom have been here for generations, are being forced to leave.

Root causes and potential solutions have been debated ad nauseam in town meetings, housing committees, at staff meetings, and in online forums. And plenty of plans to tackle the housing shortage are underway. Island Housing Trust (IHT), the most prolific developer of affordable housing, is currently building ninety-six rental apartments in Edgartown and Oak Bluffs (Meshacket Commons and Southern Tier, respectively). Employers throughout the Island are buying houses to convert them into employee units. And individual towns eagerly await the status of the MV Housing Bank legislation, which, if successful, will levy a tax on most home buyers to help pay for housing infill, accessory dwelling units, down payment assistance, and other creative ways to target the year-round housing crisis.

Still, Slarsky sees another possible solution – or, at least, another piece of the puzzle, one that hasn’t been discussed much in the sort of decision-making rooms where affordable housing projects are debated. The old postcards of Circuit Avenue remind him of work now being done along Washington Street in Boston’s South End. There, as on Circuit Avenue, he said, large buildings over time were cut down in size, losing precious square footage. They are now being built back for housing and other uses. He believes a similar strategy could work here.

“There were very few buildings on Circuit Avenue that were one story,” he said. “There were three, or four, or five stories…that aren’t there anymore. Imagine how many people could be housed in that space.”

Slarsky has imagined it. Working off a quick study of the old postcards and the number of rooms at Summercamp hotel on the Oak Bluffs waterfront, he estimates the number of units possible if the street were restored to its nineteenth-century density could be up to 750 rooms.

He’s quick to point out that he’s not talking about building five stories of affordable housing up and down Circuit Avenue. Economic models would most likely combine high-end hotel space and market-rate condominiums with affordable units. Other analyses would have to look at construction costs and the cost of temporarily displacing local businesses.

Still, given the pressing need for ever-more housing, coupled with Oak Bluffs’s recent improvements to its commercial districts, he sees a unique opportunity for the people who own businesses or buildings along Circuit Avenue to collaborate with architects and experts to ease the housing shortage and potentially profit from this kind of expansion.

The benefit of such a plan, he said, is multifold. For one, it centers the design process on the historic culture and identity of the place in which development is taking place. For another, infill around existing buildings in village centers – reclaiming them as they were originally designed and when they accommodated more people – could yield more units where the majority of seasonal workers are needed. Access to the ferry, public transportation, and availability of services additionally make in-town locations good places for people to live.

“It should be a complete vision and it should reach far – probably from where Wing Road starts, where Circuit Avenue starts to peel off to Dukes County [Avenue], and pull down to where North Bluff hits the water. Circuit Avenue should be this ‘whole’ experience,” he said.

It’s a grand vision, and one that would surely spark resistance from Circuit Avenue landowners and his fellow Oak Bluffs residents, many of whom feel their town routinely is asked to solve the problems of the Island. But in his estimate, the most common current model for building affordable housing on the Island has one major drawback, which his idea does not.

IHT’s Meshacket Commons and Southern Tier properties are set to comprise multiple acres, some of which is reserved for open space.

“A certain percentage of the site can’t be built on, and the housing is broken up into smaller units, et cetera,” he said. “But you are using a lot of a resource that is the most limited resource on the Island: land.”

It’s always been about land, of course. In 1974, as massive housing development plans threatened to eat up open space and residents sounded the alarm, the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (MVC) was established as the Island’s first comprehensive planning and regulatory body, charged with overseeing large developments, preventing contamination of natural resources, and preserving Island character.

The commission has succeeded in some areas, notably protecting rural roadsides and preventing various out-scaled commercial developments. But despite its many successes, a debate continues to rage over whether the MVC sufficiently altered the overall pace of private development on the Island. From the early 1970s to the present, housing stock grew from 5,500 units to a little more than 17,300. Of those, almost 8,900 are occupied by year-round residents.

Meanwhile, two Island conservation groups, Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation (established in 1959) and the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission (established in 1986), have preserved more than 7,000 acres of land in perpetuity for open space, recreation, fishing, and farming.

Perhaps because the building boom seemed recession-proof and was creating lots of good jobs in the 1980s and ’90s, or because a high percentage of year-rounders were descendants of longtime landowners and therefore had access to housing, or because there were still pockets of affordable woodland sites overlooked by summer home developers, it’s often said in retrospect that many Islanders failed to pay serious attention to the emerging housing crisis. If concern among year-rounders was voiced at all, it was more often about the Island getting more crowded as the full-time population crept up from 6,034 in the 1970s, to 14,901 in 2000, to more than 20,000 today.

And yet some people were paying attention.

As early as 1977, Island Elderly Housing was established to provide affordable rental units to seniors. It now oversees 165 units, mostly located in densely grouped settings, such as Hillside Village in Vineyard Haven and Woodside Village and Aidylberg Village in Oak Bluffs.

In 1986, the Dukes County Regional Housing Authority (DCRHA), a federal agency under the Department of Housing and Urban Development, was established to support residents with very low incomes and adults with disabilities. It currently manages nearly one hundred low-income rentals and acts as the tenant advocate and clearinghouse for most of the Island’s affordable housing.

Other efforts were also introduced. Individual towns began occasionally offering lotteries for “youth lots” with varying restrictions to help low- to medium-income residents obtain land where they could build houses.

In 1996, Habitat for Humanity of Martha’s Vineyard began work on the first of thirteen low-income homes it has since completed across the Island.

In 1997, architecture and building company South Mountain Company completed a four-home affordable neighborhood in West Tisbury known as Sepiessa Point. Three years later, South Mountain added a sixteen-house cooperative neighborhood in the same town in the form of Island Cohousing.

Efforts to build affordable housing became more codified in 2000 when the informal Island affordable housing forum, spearheaded by South Mountain co-founder John Abrams and others, became the nonprofit Island Affordable Housing Fund (IAHF). That, in turn, folded into the Island Housing Trust, which was formally established in 2006.

While the IAHF raised money to build awareness and support local efforts, their most prescient work took place in 2001, when they hired the first on-Island director for the DCRHA, Phillipe Jordi. (Jordi later became director of IHT.) Community development consultant John Ryan was also hired to publish an affordable housing study.

Since then, IHT has been busy. At last count, it had created 156 units that are now rented or owned by low- and moderate-income Island families. IHT typically retains ownership of the land on which such units are built. These are either rented, or they are sold at below-market rates. Buyers are allowed to resell in the future at restricted rates that allow modest profits, or they can bequeath their homes to offspring.

Still, there’s no denying that the cumulative effect of these efforts haven’t kept pace with need. As of March 2024, there were 462 families wait-listed for affordable rentals. Another 594 were in line for a chance to buy affordable homes.

All the while, home prices continue to trend higher, and the short-term rental market – which has gobbled up properties at a fast clip, raised prices, and reduced long-term rental possibilities – continues to soar.

There have been plenty of exacerbating factors along the way, of course.

Building enough affordable housing has never been just a question of creating more units more quickly, but of balancing current need with the Island’s strict zoning requirements intended to preserve the so-called unique “character of the Island.”

Plus, there’s the not-so-small matter of winning over the hearts and minds of officials, voters, and neighbors, some of whom have a general conservatism toward government action in “subsidized” housing. Others deny the need for more affordable housing altogether, while still others profess to support housing efforts, albeit with a dash of “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) resistance.

Not that anyone ever uses those words. Take, for instance, a February 2023 Vineyard Gazette article on the MVC’s approval of the Southern Tier affordable housing site. Online commenters bemoaned the number of trees at risk and expressed concerns about wastewater mitigation. That same month, in an article about allowing affordable housing to be built on private roads in Tisbury, one commenter questioned why their town was being forced to shoulder the burden. Others lamented wildlife species that could be left without homes.

To be fair, all are legitimate concerns.

Rather than question neighbors’ motives or respond to each individual complaint, Island housing advocates have focused instead on counteracting stereotypes that suggest affordable housing will negatively impact existing neighborhoods. Chief among those stereotypes: that they will be out of “Vineyard character;” or they will depress property values; or they will be cheaply built or eyesores that will fall into disrepair.

“Affordable houses are smaller, less detailed, and financed differently,” said Abrams, a longtime housing advocate now retired from South Mountain Company. But, he noted, that doesn’t mean they are either inexpensive to build or poorly constructed. On an Island where not only land but building costs are well above average, a home that requires frequent repairs or rebuilds will not be affordable for long. For this reason, Abrams asserted they must be, “in terms of performance, quality, comfort, safety, health, durability, [and] energy use, exactly the same or better than luxury houses.”

Such houses are most often designed in a simple Cape Cod style that complements the Island’s historic architecture and connects them aesthetically to their neighbors. New homes can range in size from 650 square feet for one bedroom to 1,150 square feet for three bedrooms, with sizes varying in repurposed buildings. Exterior detailing includes the use of reclaimed wood, natural cedar siding, minimal trim or surface painting, and aluminum windows and doors – all materials that require almost no maintenance. Intentionally selected interior finishes, such as natural flooring, tend to cost more up front but last longer and are cheaper in the long term for people to maintain.

IHT has also pushed back against the notion that clustering small neighborhood groupings of houses out of sight from the main road – a frequent and popular model for many of their developments – constitutes “warehousing” or segregating residents. Such claims are part of a long-standing, nationwide criticism of affordable housing units.

Rather, IHT says it sees its so-called “pocket neighborhoods” as a way of constructing socially diverse neighborhoods that will be valuable assets within the greater community. All residents must show secure income from social security or other sources, or have full-time employment on the Island.

As IHT’s former project manager Derrill Bazzy stated: “Our tenants are the people who are already your neighbors on this Island.”

“We build them this way because they’re nice neighborhoods to live in and we can site a few smaller homes on a property that might otherwise have one big one,” said Elissa Turnbull, who oversees communications for IHT. “In some instances, siting homes closer together into a pocket neighborhood has allowed us to partner with the land bank to conserve nature.”

Another oft-cited concern with IHT’s multi-family developments – one that has a faint odor of NIMBYism – is how to mitigate nitrogen emissions from septic systems that might contaminate local watersheds or private wells.

Ironically, IHT says, affordable housing production on the Island is subject to stricter environmental oversight by the MVC than are large private homes.

“I can build a five- to ten-bedroom mega mansion and just put a regular Title 5 (septic) system in, and I can put all the nitrogen I want into the pond nearby, and there’s no regulation to keep me from doing that,” said Bazzy. “But…for a development of affordable houses, there are regulations that say you can only put out so much, and if you do more you have to mitigate for it.”

To meet the stricter requirements, IHT has been working with local engineers from KleanTu, a wastewater treatment company, to install state-of-the-art septic systems that promise to eliminate 80 to 90 percent of all nitrogen emissions.

As a result, twenty units of housing built by IHT will emit the same amount of nitrogen as two three-bedroom houses. IHT has already retrofitted the KleanTu system at Scott’s Grove, a nine-unit development originally built in 2018 in West Tisbury, and installed it at Kuehn’s Way, a twenty-unit pocket neighborhood completed in Tisbury in 2022.

Importantly, this system is also planned for the sixty-unit, one-hundred-bedroom housing complex at Southern Tier, slated for completion in 2025.

In many ways, affordable developers have succeeded in persuading the public about the merits of their plans. Local resistance does seem to be diminishing. But it’s still all about land. Even if all concerns evaporated thanks to handsome architecture and environmental mitigation, planners say the Island probably can’t build its way out of its housing shortage one home, or one grouping of homes, at a time. Accordingly, other options for increasing housing stock, especially rentals, are being brought to the table, with mixed results.

This past November, voters at a West Tisbury special town meeting were asked to consider a $250,000 funding request for an Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) pilot program run by the town’s Affordable Housing Committee. In theory, the idea of using secondary structures that already exist or could be built on properties seems tailor-made for the Vineyard. It is already a common practice among some homeowners, both seasonal and year-round, to move into ADUs to facilitate lucrative short-term rentals that help them pay their taxes and otherwise afford to hang on to their primary residence. If towns could rethink existing restrictions to the construction of ADUs, the thinking goes, homeowners could be incentivized to create more year-round affordable housing.

But voters in West Tisbury overwhelmingly rejected the request, citing the lack of details in the plan. “The potential for this program to be a really good and valuable one is there; I just don’t think it’s ready for prime time yet,” said one typical voter. The affordable housing committee is expected to come back to the town with more details.

The details are likely to be complex, particularly in towns that have striven to maintain a semblance of a rural atmosphere through zoning. But there’s no escaping the reality that zoning defines the character of many existing neighborhoods on the Island, or that changing ADU restrictions is, at heart, doubling the permissible density of affected lots. A zoned three-acre parcel that goes from having one year-round household on it to two, with twice the traffic and twice the water/septic usage, becomes, in effect, 1.5-acre zoning. This is, no doubt, why concerned neighbors at the West Tisbury town meeting were intrigued but wanted to know the details.

Which brings us back to Slarsky and his old postcards of Circuit Avenue lined with multi-story buildings. On an Island with a fixed amount of acreage, there’s no way around the math: housing a growing population will mean greater density somewhere.

To date, most affordable projects have been low-slung building clusters spread across their sites to blend with the natural landscape. Even the relatively dense Meshacket Commons and Southern Tier apartment complexes are designed over spacious sites. But unless more land is magically made available for these types of large housing developments, it may no longer be possible to categorically reject more dense housing solutions on more compact sites.

If Slarsky’s idea of transforming Circuit Avenue seems a long shot, or that the revival of a Boston neighborhood might not seem an apt model for an Island of 20,000 year-round residents, Islanders might want to take a look instead at the long-term transformation of Newburyport, a historic seaside Massachusetts town with a population of 18,000. There, developers methodically planned and eventually built back or filled in parts of the downtown area that had become derelict while preserving historic structures, local businesses, and ultimately the town’s unique identity.

Michael Moskow, who died in 2022 and whose family has spent summers here since the 1960s, was one of the pioneers of the Newburyport renaissance and an early promoter of preserving culture, community, and the environment when developing. In this tradition, his son, architect Keith Moskow, and his business partner, David Hall, recently designed and developed a new multi-family neighborhood in Newburyport that might offer some useful lessons for building more densely on the Vineyard.

Their Hillside Center for Sustainable Living (HCSL) is a green co-housing complex sited on a remediated brownfield lot (a bottle and coal ash dump), which, when completed, will have forty-eight market-rate rental units, several shared community buildings, and a ten-bedroom single-room-occupancy residence for people in need of deeply affordable housing.

The development was designed to be dense, with compact multi-family housing units that leave open space for on-site farming, edible landscapes, and shared spaces and amenities. Hall and Moskow planned the neighborhood after years of accumulating land parcels to make up its four-plus-acre site, most of which required toxic cleanup. The team negotiated numerous variances that eventually allowed for the forty-eight apartments, as well as the shared ten-bedroom unit.

Obtaining such variances required communicating with neighbors and planners, as well as a supportive mayor, who leaned into housing density in the context of environmentally friendly development. (All of the units are certified LEED Platinum and powered by solar.)

From an investment perspective, HCSL was only feasible for Hall and Moskow if they structured the project as a long-term rental development, which allows them to amortize upfront costs. Rents for the apartments are on the high end for Newburyport, but by controlling every aspect of the development process – from land acquisition to permitting, design, construction, rental management, and maintenance – Hall and Moskow feel they are able to keep rates

in line. Hall also pointed out that the rents are mitigated by low to no energy costs, reduced transportation costs, and the potential for food production. HCSL is currently fully occupied, and has a waiting list for new units when they are completed.

In spite of its similarities to the much sought after bucolic Island lifestyle, Moskow seemed skeptical that something like Newburyport’s HCSL could work here. Asked why, he cited several of the typical barriers, such as land cost or zoning restrictions. He also pointed to affluent summer residents who, he suspected, would object to any dense housing development built next to their properties, regardless of the nature of the project or prospective residents.

While a core group of seasonal residents are philanthropically involved in the Island’s diverse affordable housing efforts, with some donating significant sums of money or even coveted plots of land, most tourists, summer people, and vacation home investors are not.

You might call it NIMSBY – “Not in My Second Backyard.” Or third, or fourth, or even, if you can believe it, not in my eighteenth backyard. It’s still about the land, remember. And the money.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)