Captain John Ivory, artist, peered out his front window to survey his view of the sea. He was a mariner, having circumnavigated the globe by the age of sixteen, a captain during war and peace. But this was his last command, the Dry-Tortugas, a humble beached vessel in Vineyard Haven where he lived and worked.

“I used to live at the [seamen’s] bethel, but I’m happier here,” he told a Vineyard Gazette reporter in 1950. “If I can’t see the water I’m lost.”

Satisfied with the view, Captain Ivory returned to his work, a painting of a sailboat underway, as most of his paintings were, nearly always sailing to the left. He leaned in with his homemade brush, dipped it in the salvaged bucket of boat-paint, and started on the inscription. “The Hell Ship – 1892” he wrote, his name for the Gov. Robie (which he always misspelled “Robe”), a merchant ship from his youth on which he completed his most hated voyage. He painted the ship more than forty times.

The piece was done, save for the rigging – that would go in later, in pencil, in painstaking detail. But it needed time to dry, so Ivory nailed the painting to the wall (an effective anti-theft procedure, with the side effect that many Ivory paintings are studded with holes).

His work thus secured, he was off. It was time for a drink.

Ivory was a prolific artist, with over three hundred extant works. He painted on whatever he could find (shingles, seashells, plates, plywood), and sold them cheap, often just enough to buy a bottle of wine. The paintings are simple, folk art, sometimes repetitious but each one honest, starkly beautiful, and meticulously accurate. His work and his story have proven to be oddly compelling to generations of Island art collectors.

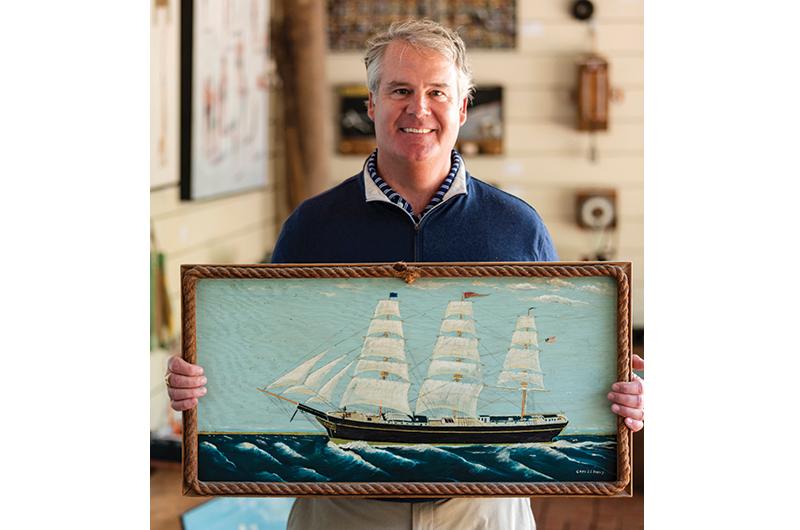

“It’s a Vineyard story. Anything of this place means a lot to people,” said Chris Morse, owner of the Granary Gallery in West Tisbury. Morse began collecting Ivory paintings in the 1980s, when the occasional dusty sailboat painting could still be found at the odd Island yard sale. Now his walls are studded with them – the Gov. Robie, the C.W. Morgan, even the famous collision of the Covington and Port Hunter (an unusual feat of perspective for the captain). “It’s Vineyard naïve art, perfect for a Vineyard cottage,” Morse said, emphasizing that he never sells his Ivorys. He feels they are too special, too tied to this place.

“They convey a provincial feeling, that the man who painted these had a real life,” said Jane Slater, a retired Chilmark art dealer who sold her fair share of Ivorys at her store, Over South Antiques. Slater is perhaps the foremost expert on the artist. At ninety-one, she is one of the last living members of the John Ivory Society, a group that dedicated itself to researching and cataloguing his work. In 2011, Slater led a talk about Ivory’s life and legacy at the Vineyard Haven Public Library, now host to a permanent exhibit of twelve Ivory paintings. It was a salty forum, giving rise to many reminiscences of the larger-than-life mariner.

Ivory was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1878 and little is known of his early years. At the age of fourteen he took his first job at sea and boarded a New York merchant clipper destined for Japan. It was the hated Gov. Robie. By his telling, the journey was a nightmare. In an inscription on one of his paintings, he related how the voyage’s chief mate, a Mr. Townsend, went overboard in the China Sea. “I could see him swimming very good…the small boat almost reached him,” he wrote, but then “all of a sudden he went down never to return. Very sad – shark got him.”

The crew unloaded their primary cargo of cask oil in Japan, transported a load of bamboo and straw to Hong Kong, then headed back to New York, at which point he had completed his first circumnavigation. For the whole trip, he wrote, “pay was something like fifty dollars.”

“It was a terrible experience and he never got over it,” Slater said. Nonetheless, Ivory picked up a few choice Japanese phrases on the journey, which he would employ in moments of high emotion.

Despite a harrowing first voyage, he remained on the ocean for the next fifty years, working his way up to captain. He was eventually designated as a Master Mariner with unlimited license, the

highest grade a seaman can achieve. He served in the merchant marine in both the Spanish-American War and World War I. “We have to think of him as a merchant mariner of the highest esteem,” said Ralph Packer, another collector of Ivory’s paintings.

Eventually, Ivory picked Vineyard Haven as his final port of call. He was sixty when he settled in the Dry-Tortugas, and he lived to eighty-six, spending summers on the beach near the present-day Black Dog Tavern and winters in the bethel. He died in a Vineyard Haven nursing home in 1964.

An imposing figure in his day, Ivory’s body was covered in tattoos. Around his wrist, a blue snake inked in Japan; on his arms, two American warships, the Lancaster and the Maine; and on his feet, a pig and a rooster. Asked why he chose two farm animals, he replied: “Ham and eggs around the world, of course.” He was also a pugilist in his youth and was known to teach young Tisbury boys how to box.

Soon after settling on the Island, he began to suffer from memory loss. Though he vividly remembered youthful journeyings, he had trouble with more recent occurrences. According to an article from The Grapevine, a 1980s alternative Island newspaper, he saw a doctor who diagnosed him with massive head trauma. The doctor offered to operate, but Ivory declined. “It was the way he wanted to live,” the writer said. “To live in the past with his beloved and despised ships.”

He also had what Slater termed “a typical artist’s weakness for drink,” a fact that drew some controversy as the artist’s legacy grew. In 1981, following an exhibition of her father’s work, one of Captain Ivory’s daughters wrote a letter to the Vineyard Gazette, a remembrance of her father, castigating those who she thought took advantage of him. “He always used to say to me: ‘the finest thing in this world you can do is to help somebody and make them happy.’ I never forgot,” she wrote. “He always called a drink ‘a smile.’”

According to Morse, friends and collectors who bought Ivory paints or new shoes would often turn around to find he had sold them, presumably to buy himself a bottle. “A lot of people will say that he was taken advantage of,” Slater said, “but at the time he had no idea that his work was going to be worth anything, and neither did the people who were buying them.”

And there were many in Vineyard Haven who made it their business to care for the old mariner, on his own terms. “That was my era,” said Eugene DeCosta, who grew up in Vineyard Haven while Ivory was still living in the Dry-Tortugas. “It was a nice place to live, everybody watched out for everybody….Every Saturday I used to bring a plate of hot dogs, beans, and cornbread to him and another old guy who lived out there.”

Stuart and Dorothy Bangs, who worked at Bangs Market, also took care of him. “He didn’t want for food, and he didn’t want for clothing, and he preferred to live where he was,” Dorothy said on the evening of Slater’s 2011 talk. (Both Stuart and Dorothy Bangs are now deceased.)

Ivory could be ornery at times, and it took him a few introductions to remember a face, but he made many friends in his years on the beach.

And over the years, as Ivory’s oeuvre multiplied, many Islanders grew their collections. Most of those paintings remain on the Island to this day.

In the years after his death, Captain Ivory’s legend increased, as did the value of his work. As it turned out, this simple, self-taught style threatened also to be the undoing of his legacy.

“Ted [Hewett] always used to say that anyone could copy a John Ivory with their left hand,” said Morse, recalling his own relationship with the John Ivory Society. Many professional artists, he explained, set up organizations to manage and verify their collections after their death. Ivory, of course, set up no such group.

And so, following an exhibit of Ivory paintings at the Martha’s Vineyard National Bank in 1981, three Islanders came together to form the society: Bill Honey, Ted Hewett, and Stuart Bangs. It is thanks to them (and Slater, a later inductee to the group) that Ivory’s work can be identified with such reliability. The society operated through 2011 when, after a final burst of authentications, Slater archived the society.

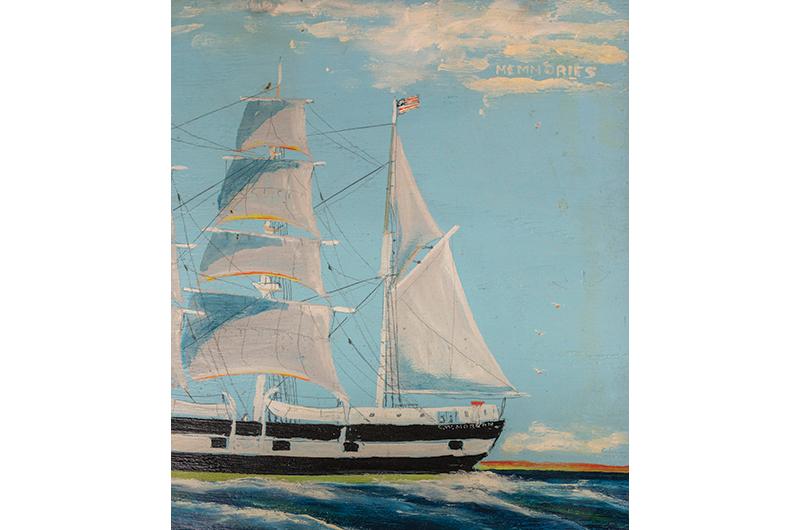

There is an oft repeated, oft unnoticed detail in many Ivory paintings, an aspiration tucked amongst the clouds. There in pale yellow paint, characteristically misspelled, he inscribed one word over and over: “memmories.”

Memories are indeed key to the lasting appeal of Ivory’s work – the memories of a sailor who spent his life at sea, and the memories of all those Islanders whose lives he touched while ashore. It was on that note that Slater ended her talk on Ivory’s work, with a simple admonition: “Let’s keep John Ivory alive as long as we can.”