So much of the world’s natural beauty is fleeting – the sunsets that splash waves of magenta and indigo across the horizon; the symphony of birdsong; snowflakes. For just about forever, artists have tried to capture the ephemeral. Few, however, have managed to outwit Mother Nature and appropriate her handiwork as skillfully as has Corinna Kaufman.

For many decades she has carefully preserved and presented still lifes and abstractions of unadulterated seaweed that have attracted the attention of celebrities, private collectors, and gallery owners both on Island and in New York City. Her compositions are displayed at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital in Oak Bluffs and the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in Vineyard Haven, and prints and cards of her artwork are available for purchase at stores around the Island, including Cronig’s Markets and Alley’s General Store.

Kaufman’s unusual choice of medium continues a venerable tradition of seaweed pressing that peaked during the nineteenth century. Standing in her Aquinnah studio and gallery space earlier this year, she pointed to a small seaweed arrangement in an oval metallic Victorian-style frame. “Did you know Queen Victoria herself made seaweed art?” she asked. Framing it an unusual way, she explained, makes it seem like a period piece.

Kaufman wasn’t aware of the lofty history of the genre or its most famous purveyors when, as a young child, she found herself drawn to the work. She just liked seaweed, and the sea – really, everything connected to it. Her love for the water, she believes, began before she was born, when her mother would spear fish off the beaches of Gay Head (now Aquinnah) while pregnant with her.

“I’m sure I absorbed that love,” she said. “My first toys were things of the sea.”

Over the years, her preoccupation with all things natural and nautical increased. When Kaufman was five, her parents purchased the former Gay Head Inn and turned it into a summer home. She has spent part of almost every year there since, and the front room now hosts The Seaweed Art Gallery in which she seasonally showcases everything from greeting cards to larger scale, framed twenty-eight-by-thirty-inch compositions. Looking out the living room window and down to the shore, she recalled long days spent exploring tidal pools, sand dunes, and shallows. At the age of six, she began snorkeling. As a preteen, she took up spear fishing. “I could barely wait for the sun to come up before I was on the beach,” she said.

Kaufman was so entranced by the world outside her door that she would lose all sense of time until her mother played an antique tin horn, signaling that it was time for dinner. Other go-to hobbies included collecting fossils and helping injured animals. “I once nursed a seagull back to health for three months and then watched it over the following summers,” she said. “That was the start of my work as a healer.” It was also the source of her family’s nickname for her: “Florence Nightingale for Animals.”

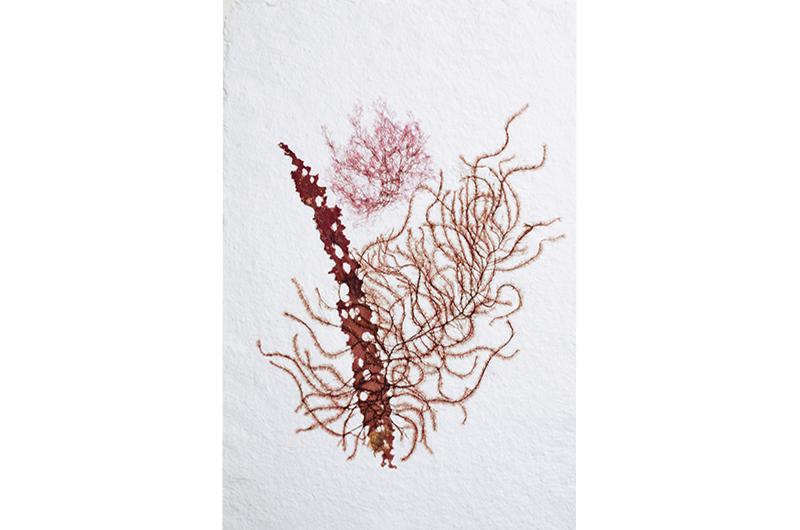

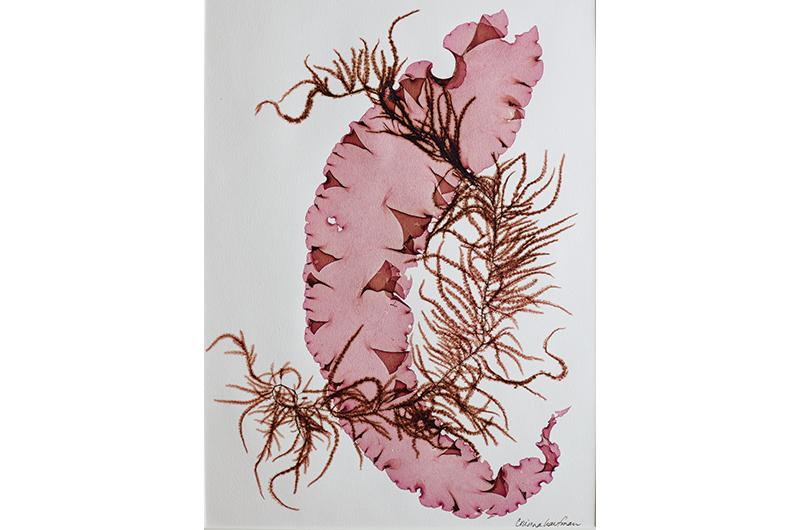

And, of course, she had a fascination with seaweed – particularly the beautiful pink and purple fronds and delicate vein-like plants that undulated in the Island waters.

When Kaufman was approximately twelve years old, she visited Bunch of Grapes Bookstore in Vineyard Haven with her parents and came across a bookmark that featured green seaweed artfully displayed. It was the work of Island-based seaweed artist Rose Treat, a self-taught naturalist who was known in both academic and art circles for her depth of knowledge and beautiful collages. Treat’s work spoke to her.

“I wanted to do what she was doing,” she said. Back at home, she began experimenting with ways to gather various types of organic matter and suspend their colors and shapes in time. She decorated cards with her findings, wrapping each in Saran wrap and sealing them with Scotch tape. When she was satisfied with the finished product, she would walk to the Gay Head Cliffs to deliver her goods to souvenir shops.

“I did this all by myself,” she explained, “with my thumbs and legs.”

Her work caught the attention of summer tourists, as well as that of famed photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt, who recognized her talent when she was only fifteen years old. Eisenstaedt, who vacationed every August on the Vineyard for fifty years, often came to Aquinnah to photograph the cliffs, Kaufman explained. “We saw him all the time.”

In 1969, the photographer purchased all of Kaufman’s cards from Lucille Vanderhoop’s shop and asked to meet the artist. The meeting didn’t happen, as Kaufman was at the mercy of her parents to arrange such a get-together. “They were European socialites, probably with their minds on other things,” she explained of her parents, who hailed from Italy and Austria. Eisenstaedt didn’t forget her, however. Years later, she was shocked to get a call from him. He told her he still had all her cards and appreciated the beauty of her work.

He wasn’t alone. To this day, Vanderhoop’s niece, Adriana Ignacio, who now owns the On the Cliffs gift shop where Kaufman sold her art as a child, said she is occasionally asked for her “real seaweed” stationery.

Now entering her seventh decade, Kaufman sports hip red glasses, wampum stud earrings, and the exuberance of a puppy. She exudes pride in her early successes, as well as the wisdom of a person who has gone through travails and found focus and therapy in her art. “The ocean has been my family, my home, my church; it’s where I want to be,” she said, gesturing toward the Sound. “I go to other beaches, but there is nothing like this one….When I work with parts of the ocean, all that love, emotion, healing is getting transmitted in my art.”

Hopping up from her place on the couch, she returned with a twelve-to-twenty-five-million-year-old fossil: a bowling-ball-sized vertebrae she found long ago on the beach behind her house. Next was a pudding stone, an ancient sandy conglomerate packed with easy-to-see shells, pebbles, and sharks’ teeth.

“That’s how I grew up,” she said, “fascinated by the incredibleness of this area.”

Despite the auspicious start to her career, Kaufman’s art took a backseat beginning in her twenties. She was struggling with a severe eating disorder and trying to establish her identity. Unsure what to do next, she headed to California. While there, she supported herself by detailing cars and yachts, muddling through for a while. She trained to become a massage therapist and built a practice. She also trained as a clinical hypnotherapist and is now an instructor.

Kaufman said she loves helping those suffering from addiction, anxiety, and depression. She still sees clients of all ages.

“For so long, I was stuck in California with no money to get back to Gay Head,” she said. “I missed it so much.”

That changed in 2000, when she met her husband, Ken Kaufman, who formerly headed up a health and healing expo. When she finally brought him to the Vineyard, he immediately fell in love. The pair began spending significant amounts of time on the Island. In 2004, she self-published a pocket-sized self-help book, How to Quit Whatever You Want to Quit: Ten Steps to Overcoming Lifelong Addictions, which can be found at Cronig’s Markets and online. She wrote it, she said, believing that when she was at her lowest, she would have found this kind of advice helpful.

Ken now runs the business side of their endeavors. “I make art and he is chief of everything else…he’s my greatest supporter,” she said.And these days, the biggest difficulty she often faces when creating her art is dealing with the whims of the ocean. That whimsy also feeds her imagination.

Kaufman has gathered the silica she finds sparkling in waves, taking it home and sprinkling it like glitter on her pieces. She has highlighted the tiny mussels that cling to her specimens, especially pink sea lettuce, inviting viewers to take a closer look. Eight years ago, after noticing a new kind of seaweed with a black color palette near her shoreline, she began a “winter series,” which showcases designs that look like trees with bare branches. The starkness of these pieces suggest the simplicity and elegance of Japanese art. It’s a sharp contrast to her colorful signature arrangements, which resemble floral bouquets, jellyfish, or leaves dancing in a summer breeze. Nobody believes her, she said with a shrug, but all the hues are 100 percent natural.

Kaufman creates the pieces in her home studio alongside Ken, whom she credits with braving frequent nights of seaweed drying on the sofa. Occasionally, their living room smells like low tide. She uses no tools, shiny glues, or resins to manipulate the seaweed, she said. Instead, she relies on experience. She has learned through trial and error which processes and seaweed varieties have staying power, and she is always learning and tweaking things. A few years ago, for instance, she switched from using rice paper to handmade paper.

Her eyes gleam with pride as she holds up a piece of art she made for her parents almost fifty years ago. “This has stayed intact,” she said.

As for what processes allow her art to endure, Kaufman won’t divulge her secrets. “I feel I owe it to my little-girl self who began experimenting with the wonders of seaweed not to overshare about my process…everything I do is a sacred

reproduction of my life’s journey,” she explained.

And yet she has begun sharing some of her knowledge and love for the art form with children. Recently, she started teaching children ages five to eleven, both privately at her gallery and publicly through venues such as the Chilmark Community Center and Island libraries. The enthusiasm of the kids excites her. “Parents later tell me that our time together was one of the highlights of their summer,” she said.

During her classes, Kaufman leads expeditions to the waters near her home, where the students search for seaweed and learn which types works well on paper and and how to arrange their findings. Though she offers advice, she allows students the freedom to add whatever they discover, from pebbles to shells, to their creations. Kaufman then dries, presses, and mails them the final product.

“Working with kids before they might deal with addiction, like I did, can give them tools to express themselves so they don’t have to suppress thoughts and emotions…they learn to spot beauty and see it in unexpected places,” she said.

To this day, that fluid expression of thoughts and emotions continues to play an important role in her life. Seated in her studio, discussing the highs and lows of her career that flourished, then sputtered, and flourished again, Kaufman wondered aloud whether her journey to becoming an artist was inevitable. Perhaps it really was preordained all those years ago, during long days spent by the sea, and spurred on by a chance encounter with a seaweed bookmark in Vineyard Haven.

Perhaps if she had made other choices, things would have turned out differently.

“If I was more of a student,” she mused, “I would have been an archeologist or veterinarian.”

Then again, unlike naturalist/artist Treat, whose work inspired Kaufman so many years ago, Kaufman acknowledges that she has never been much interested in the science of her work.

Sure, she can identify a few varieties and knows the difference between various species. But above all else, she is content to enjoy nature’s gifts. Her gift is to preserve and share them with others.