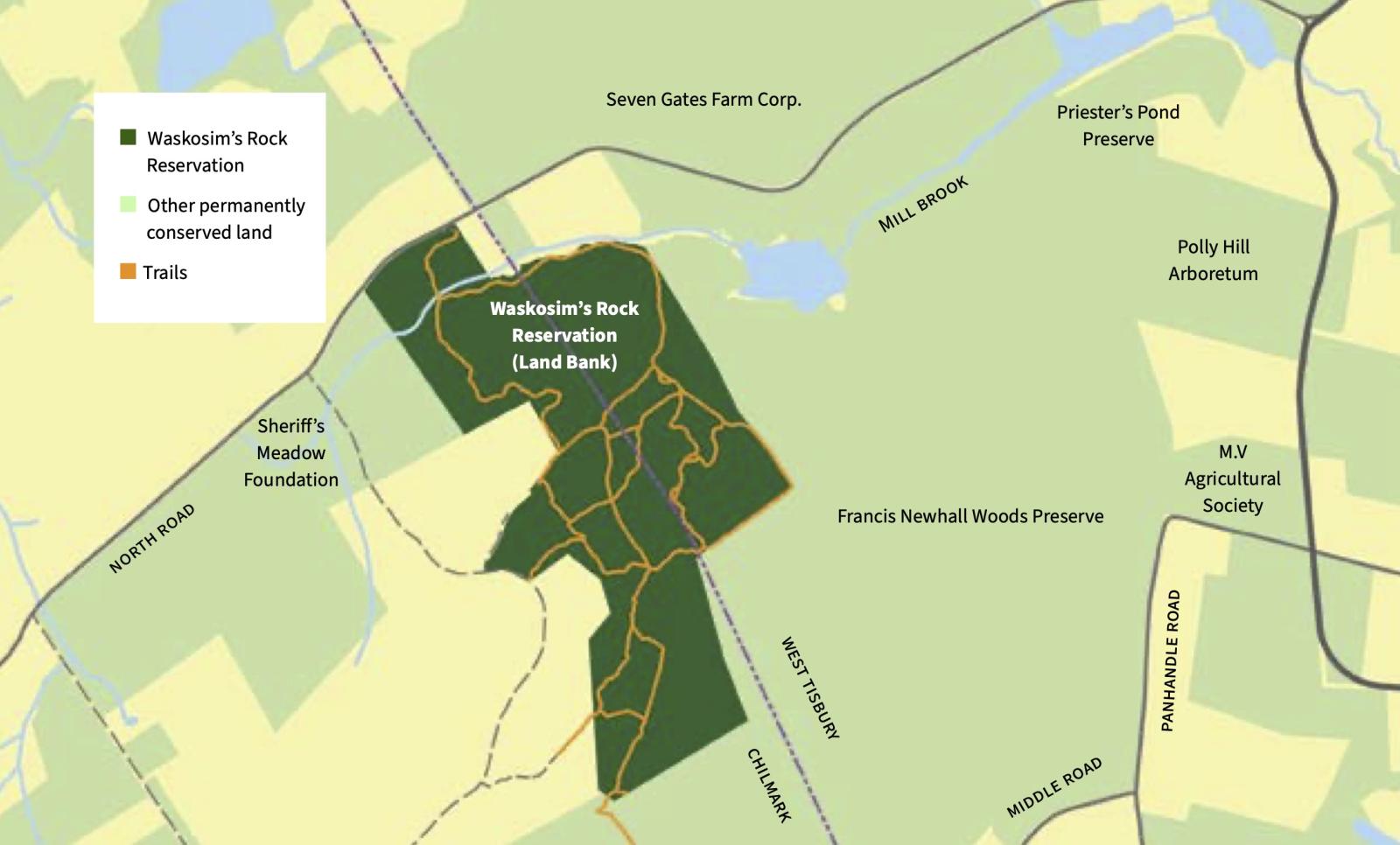

At Waskosim’s Rock Reservation in Chilmark, a 185-acre swath of public land owned and operated by the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission, it’s easy to see history’s footprints. Most famously, history is visible in the giant, eponymous boulder, left behind some 20,000 years ago by the retreating Laurentide ice sheet and known more recently as the endpoint of a wall separating English from Wampanoag land. But history is also written in the site’s topography: ridges made of glacial till and valleys formed by rushing glacial melt. It’s visible in the property’s picturesque pastures, crisscrossed by rough stone walls – the colonists’ way of domesticating land strewn with rocks. It’s there in the gradually maturing forests, which began expanding more than a century ago when sheep farming dwindled. It’s there in the burbling Mill Brook, which once powered several gristmills as it wended southward to Tisbury Great Pond. And it’s there in the remains of a seventeenth-century farmstead built by James Allen, the first patentee of the Manor of Tisbury: a paddock, a pair of cellar holes, the capstone of a well, and a pile of chimney bricks.

But there’s another, more recent bit of history embedded in this land as well: the struggle in the late 1980s to save it from a plan to install dozens of vacation homes. Such plans weren’t unusual for the time. The pace of development on the Island had been steadily accelerating since the late 1960s, when the first big subdivisions cropped up at such locations as Waterview Farms on Sengekontacket Pond in Oak Bluffs. Concern about suburbanization was enough that, in the early 1970s, Senator Ted Kennedy introduced a bill to create a national seashore-like “trust” on the Vineyard and Nantucket that would restrict development and give federal authorities oversight.

Although that effort died in Congress, in 1974 the Commonwealth of Massachusetts created the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (MVC), which had unprecedented authority to regulate large scale development. In 1986 voters sought to stem the continued loss of open land by creating the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission, with a stream of revenue from a 2 percent tax on most real estate transactions dedicated to buying and conserving land for the public. Waskosim’s would go on to become the land bank’s first major acquisition.

But it very well might not have happened that way. The open spaces and woodland trails at Waskosim’s are in fact the result of a prolonged community effort with far-reaching consequences: it set the stage for the preservation of hundreds of additional acres in the area, enabled the brand-new land bank to make good on the promise that it could improve the trajectory of land use on the Island, and inspired conservationists with an example of what was possible with community engagement.

The messy, multi-pronged effort lasted four years – long enough for a pair of doggedly persistent developers to be worn down by the whack-a-mole efforts of a motley group of neighbors, including my parents, who were even more dogged. And it served as a signal to the community that even when “progress” seems inevitable, some things are worth fighting for. Even more important, it showed that some battles can be won.

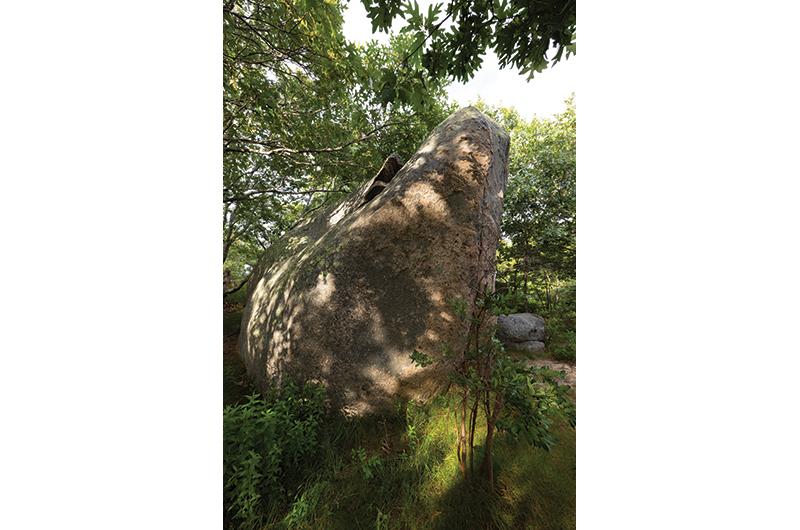

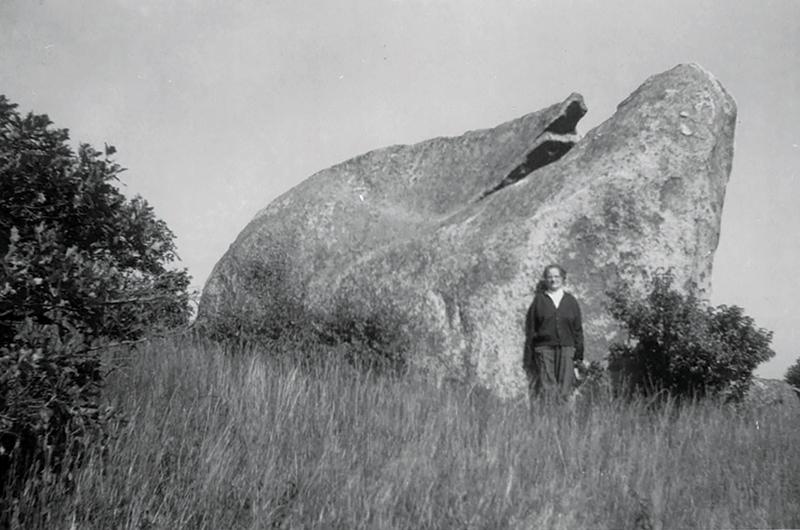

First, let’s talk about the rock: Waskosim’s Rock. Or Weskoseems. Wascosim’s. “A place called wasqusims.” (This last from town records in 1681–1682, according to Charles Banks, in his three-volume, 1911 history of the Island.) “Waskosim” means “new rock,” in the Wampanoag tongue, according to the Aquinnah tribe’s website. It’s also been said to mean “whale turned to stone.”

Which would be a fitting name for the rock, if true. As big as a one-car garage, the granite behemoth rears up from the ground like a breaching whale, split diagonally as if opening its mouth for a gulp of krill before plunging back into the deep. The rock’s unlikely location atop a hill, its dramatic crack, and its astonishing size made it a landmark for both indigenous people and colonial settlers at a time when the land had been cleared for farming and the rock was visible from miles away.

“In other days,” Vineyard Gazette columnist Joseph Chase Allen wrote in a 1959 article, “people from everywhere went to the hill, fascinated by the view which they had obtained from afar.” Now, he wrote, the rock was hidden from view and hard to reach. “Today, wrapped in a loneliness as complete as at the beginning of time, Weskoseems lies like a slumbering monster, guarding whatever secrets it may possess.”

In the ensuing decades, the rock, located on private property and increasingly obscured as the forest grew up around it, was largely forgotten. But in 1986, it returned to the public eye, showing up as a feature on a subdivision plan submitted to the Chilmark and West Tisbury planning boards. James Crocker Jr. and Joseph Clair, owners of a Cape Cod real estate firm and a group of car dealerships, respectively, had formed Mill Brook Trust, which purchased the rock and its surrounding land with hopes of building more than thirty homes on site.

Crocker Jr. died in 2019. His business partner, Clair, did not return calls for this article. But as land bank director James Lengyel recalls Crocker Jr. telling him at the time, the developer had a particular plan in mind for the rock itself. He wanted to incorporate it into his own home. He wanted to build his house around the rock.

Ultimately, that house was not to be.

In 1988 – thirty-five years ago this year – the MVC voted to designate Waskosim’s Rock and twenty-two acres around it a “Special Place” under the category of “Hilltop Districts,” where building would be prohibited above a certain elevation and require a special permit below it. The purpose of hilltop districts is to help preserve the Island’s rural character – a key element of the MVC’s mission – by preventing intensive development in visually prominent places. Nobody would be allowed to build near Waskosim’s Rock.

But while the MVC decision thwarted Crocker Jr.’s house plan and reduced the number of houses he and his partner would be able to place on their parcel, Mill Brook Trust continued to submit plans to develop the rest of the property.

They were repeatedly stymied by roadblocks thrown in their path by Tea Lane–area neighbors and conservationists. Virginia “Ginny” Jones, owner of an abutting parcel and now a member of the West Tisbury Planning Board, remembers the battle with relish. “It was a long and glorious fight,” she says.

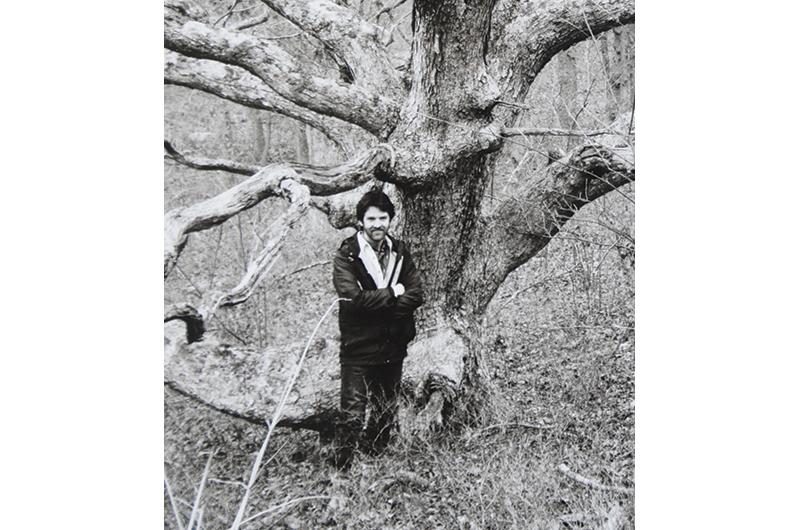

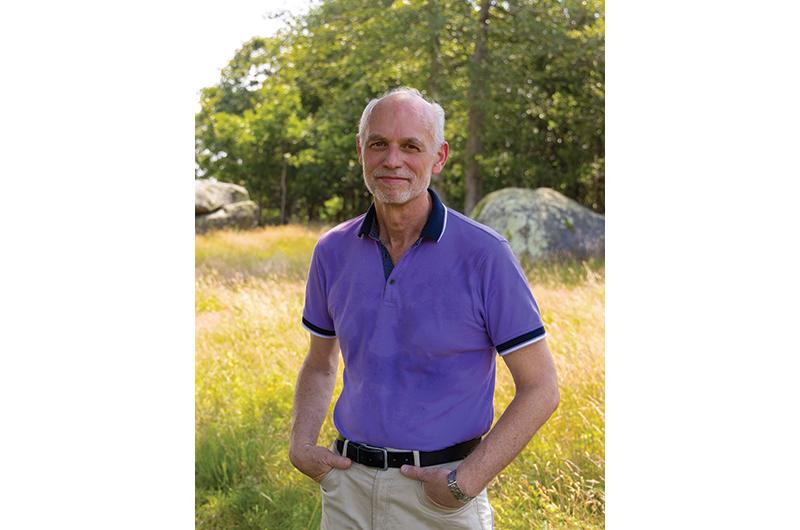

Although he’s modest and doesn’t like to take credit, the person who conceived much of the strategy for the resistance effort was Brendan O’Neill, the longtime executive director of the Vineyard Conservation Society (VCS) who retired from the position in May. A recently minted lawyer who learned the Vineyard’s byways by driving a cab here in the summers during college and law school, O’Neill had only been on the job for a year in 1986 and was full of ideas. His organization, a scrappy, independent advocacy group that serves as a watchdog for the environment Island-wide, was the right one for the job.

Even so, both O’Neill and neighbors agree that VCS’s role was to support rather than to lead. “From the start,” says one of those neighbors, Bob Skydell, in a recent email, “the effort to preserve [the Waskosim’s property] came from a small handful of neighbors.”

Skydell, a brash and energetic entrepreneur who would later found the Dry Town Café, Offshore Ale Co., and Fiddlehead Farm, was at that time raising goats – he named two of them “Crocker” and “Clair” – and building himself a house near Tea Lane Nursery. Skydell recalls beating a path through the woods to strategy sessions at the home of Charles Fitzgerald and Kathy Cerick, who owned In the Woods, a shop in Edgartown. Also involved in the drama were Frank, Peter, and Heidi Dunkl, siblings who owned twenty-three acres between Old Farm Road and North Road. Musicians, craftspeople, and self-taught Volkswagen repair specialists, the Dunkls lived in a house they had built with hand tools in the 1960s and raised honeybees.

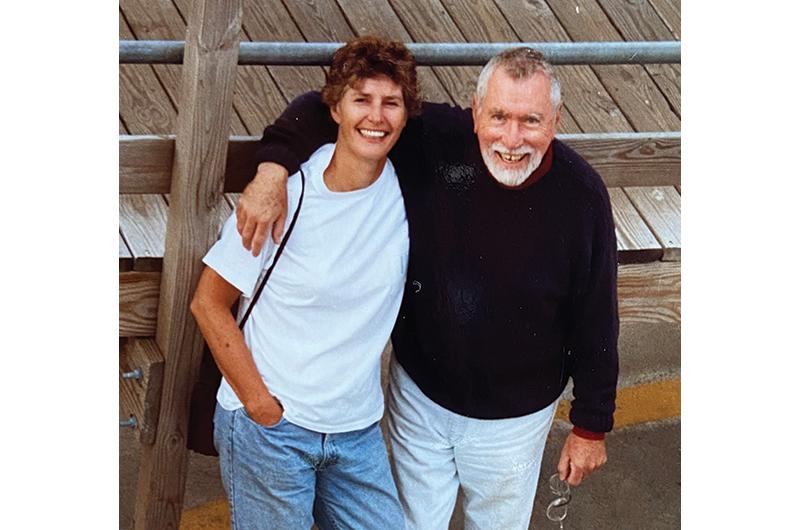

My parents, too, were part of that group. My father, William Goldsmith, a retired American studies professor and presidential scholar with a rhetorical gift who favored corduroy jackets and, often, a piece of rope for a belt, took the lead. My mother, Marianne Goldsmith, a pediatrician in the process of becoming a child psychiatrist, was in full support.

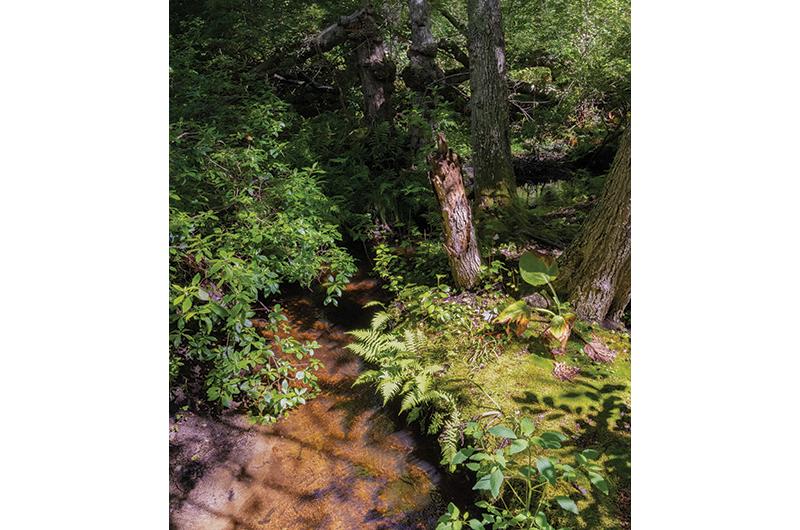

Although many factors made the Waskosim’s property special, arguably the most important was the fact that much of it lay within the watershed of the Mill Brook, which runs across the north end of the parcel. The Island’s longest stream, it is the primary source of fresh water for Tisbury Great Pond, an important shellfish resource that is currently listed as “impaired,” primarily as a result of excess nitrogen caused by septic systems and fertilizer runoff. It’s also a critical habitat for the threatened American brook lamprey and other fish. Protecting the land around the brook is a priority for many environmental groups.

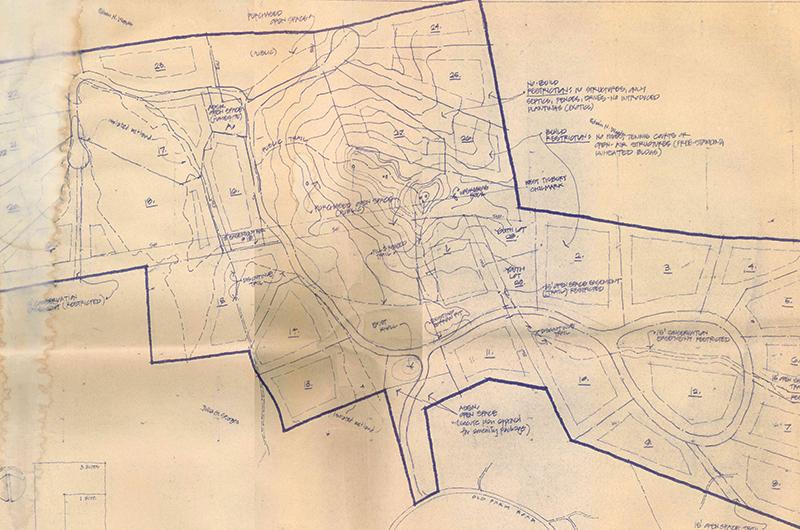

As far back as 1978, VCS had commissioned a study of the Waskosim’s property to assess its environmental importance and consider the feasibility of saving it from development. In the fall of 1986, when VCS learned the owners, Tea Lane Associates founders and real estate agents Eleanor Pearlson and Julia Sturges, were in negotiations with a developer to build thirty-two houses on 137 acres there, the group voiced its opposition. Primary access was planned via Old Farm Road through the Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation’s Roth Woodlands sanctuary, which protects the headwaters of the pristine Mill Brook. “Wetlands would be disturbed, ancient ways eliminated, and a 10,000-gallon fiberglass water tank buried under the Allen homestead ruins,” O’Neill wrote in a special edition of the VCS newsletter in 1990.

My parents were incensed about the plan. A decade earlier, they had purchased a lot off Tea Lane from Sturges and Pearlson and built a summer house there. They had been told that Tea Lane Associates’ master plan for the area, created by Harvard landscape architect Peter Hornbeck, included 100 acres of open space around Waskosim’s Rock that were shielded from development by protective covenants.

Joined by three neighbors, they filed suit in September of 1986 against Mill Brook Trust and Tea Lane Associates, seeking enforcement of those covenants. It was a painful conflict for my parents, as they were friendly with Pearlson and Sturges, who they knew had come to Tea Lane in 1967 with love for the land and idealistic plans for sensitive development, but who had struggled financially in recent years.

And it was risky. In an effort to scare them off, both sets of defendants countersued, seeking damages. “We could have been wiped out,” my dad, who died in 2010, told the Gazette some years later. But my folks were already in love with the Waskosim’s property, which we’d explored often on family outings. And my father, a former union organizer and a veteran of the civil rights movement, was nothing if not a fighter when he felt his cause was just.

The case was argued in Boston before Superior Court Judge Elbert Tuttle and in March 1987, the decision came down: case dismissed. The judge found that the protective covenants described in the master plan were not enforceable because they did not appear in the Tea Lane residents’ deeds. The countersuits, too, were dismissed.

In November, Crocker Jr. and Clair closed on the Waskosim’s property. It looked as if they would get to build there after all. During the yearlong delay that the lawsuit had created, however, the sale of the property could not proceed, and a window of opportunity was created for the community to prepare additional courses of action. In perhaps the most quixotic effort of all, Charles Fitzgerald and Kathy Cerick offered Tea Lane Associates $5.4 million for the property, and made a $20,000 deposit. “I had no idea where the money [would come from],” Fitzgerald says. “I just wanted to be in the way.” (The couple would later buy up hundreds of acres of Maine forest to protect the Alder Stream watershed.)

VCS’s O’Neill took charge of documenting what was special about the Waskosim’s parcel. During visits to the property, some accompanied by a botanist, he discovered several cranefly orchids (Tipularia discolor), a rare plant with an unusual life cycle. Its leaves emerge in the fall and survive the winter, only to disappear in spring. At the time, the flower was considered extinct in Massachusetts. (The species is still listed as endangered in the state.)

O’Neill’s team also recorded other species of special concern in Massachusetts, including bush rockrose, sandplain flax, and an eastern box turtle, a species that was rapidly disappearing in the state. On one visit to the site with Skydell, O’Neill remembers a long black racer snake slithering out of James Allen’s ancient well. And after one “robust” rainstorm, O’Neill says, he went into the woods and shot video of sheets of surface water flowing into the Mill Brook. O’Neill brought this information to every public hearing he attended – seventeen in all, by his count.

The neighbors also attended these hearings, which took place first before the Chilmark and West Tisbury planning boards and later before the MVC, to raise objections to each new iteration of the Mill Brook Plan. (One later proposal, for instance, called for building twenty-eight houses on 145 acres.)

The Dunkls focused their energy on convincing officials that Old Farm Road, a curved dirt road that connects North Road to Tea Lane and was the only possible access road for the landlocked property, was inadequate for the traffic the subdivision would generate. At its North Road end, the road narrows to a single lane as it crosses a marsh that is owned by the Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation and contains the headwaters of the Mill Brook. Cars that meet there head-on sometimes have to back up to find a turnout. The Dunkls argued that additional traffic – or any attempt to widen the road – could pollute the marsh as well as the brook. Rebecca Gilbert, a concerned environmentalist whose Native Earth Teaching Farm is near the Waskosim’s property, remembers Frank and his siblings coming to public hearings armed with a large photo from a 1973 incident in which a fire truck slid off the road into the marsh. How would public services reach the development? Frank demanded. “They carried it to every meeting and kept popping up with it,” she recalls.

As for the Tea Lane entry point to Old Farm Road, Skydell had another strategy. “I remember being cautioned by the Chilmark Planning Board that my diatribe about Tea Lane not being able to serve as adequate access could backfire and end up with the developer insisting that the road” – a historic dirt road beloved by residents for its cantankerous twists and narrow spots that keep traffic to a minimum – “be widened.” After consultation with O’Neill, he decided a better course of action would be to try to make such widening impossible by recruiting an assortment of neighbors to put fifty-foot conservation restrictions on their property along the roadway. “I went to work going down every driveway along both sides of the length of Tea Lane to see if I could get owners to sign a letter of intent,” he writes. “We didn’t need more than a few ‘choke points.'"

In the end, ten Tea Lane landowners agreed to the conservation restrictions.

Still, Crocker Jr. and Clair continued their efforts – even after the MVC denied their plan in the summer of 1988. They filed suit against the commission with the novel argument that the group’s denial was void – and, indeed, that the Chilmark portion of their plan had been constructively approved – because more than ninety days had elapsed between the date they filed it with the Chilmark Planning Board and the date of the MVC denial. The trial court ruled against the developers, and the decision was upheld by the state supreme court.

Although the land bank is a public entity and cannot play a role in any dispute over private land, it was nevertheless preparing for the possibility that Crocker Jr. and Clair would give up the ghost. The Chilmark and West Tisbury land bank advisory boards had each voted unanimously to recommend acquisition of the property, even though it was not yet available.

That same year, the land bank purchased eighteen abutting acres on North Road from the family of horticulturist Polly Hill. “It was all part of putting the building blocks into place because the land bank was hoping and expecting that someday this property [Waskosim’s] would become available,” says land bank executive director Lengyel. “It was just simply a matter of arriving at the moment when there was a willing seller.”

In the end, it was the pressure of servicing a $4 million mortgage on a property that was not producing income that induced the developer to sell, Lengyel says. “The bank had painted him into a corner.” In April of 1990, Crocker Jr. and Clair sold the land that would become the core of Waskosim’s Rock Reservation to the land bank for $3.5 million, just $200,000 more than they had paid for it in 1987. Combined with the eighteen acres the land bank had already purchased and an additional parcel they would purchase from the Seven Gates Farm Corporation, the reservation eventually grew to 185 acres, accessible from North Road.

“Moment of Triumph,” was the headline of an editorial in the Vineyard Gazette. “For the first time, a community has rallied around the land bank and its principle of preservation in an effort which even the most optimistic framers of the agency would have been hard put to envision.”

The land bank’s purchase of Waskosim’s Rock Reservation led to a blossoming of conservation efforts in the region. On the day the purchase was announced, Virginia Jones and her then-husband, Everett Jones, announced they were placing conservation restrictions on forty-seven abutting acres. The Dunkl family also announced restrictions on their parcel. (In 2013, they sold their land to the nonprofit Island Grown Initiative, retaining a life estate.) And in 1991, Edwin “Bob” and Jeanne Woods placed a conservation restriction on 500 acres of unspoiled woodlands adjacent to Waskosim’s. Twenty-two years later, they permanently gifted that land to The Nature Conservancy.

Preserving the Waskosim’s property was a necessary precondition for most, if not all, of these gifts. “[The land bank was] assured by neighbors... that if it was able to conserve this property, it would act as a sort of octane or a springboard and that the neighbors would then be willing to conserve their own property,” says Lengyel.

“These conservation achievements tend to have a contagious quality,” explains O’Neill, who draws a line forward from the Waskosim’s deal and the Woods donation to the preservation of Polly Hill Arboretum and the recent preservation of the Stillpoint property in West Tisbury, which is also located in the Mill Brook watershed. Most of the land on the other side of North Road, meanwhile, was already well-protected by Seven Gates Farm’s decision in 1975 to put most of its acreage under conservation easement with the Trustees of Reservations.

“The result,” O’Neill says, “is sizable protection of the Mill Brook watershed.”

In the end, it was the collaboration between individuals, private groups, and public agencies that made this result possible. “All of these entities worked together to arrive at the best resolution for the property, which in the land bank’s opinion is conservation,” says Lengeyl.

At the core of the effort was the role of individual community members who worked in concert to achieve their goals. The Tea Lane landowners took risks and spent countless hours working to preserve a piece of land they found valuable. Once it was clear what was possible, the effort snowballed, giving other landowners confidence that if they committed their property – or some of their property – to conservation, the end result would be something greater than the sum of its parts.

“I’m very proud of this part of the Island because of how much land is now preserved and will be forever,” says Virginia Jones. “That gives me an enormous amount of pleasure.”

It gives me pleasure as well. I’m proud of my parents’ role in this saga, but that’s not the only reason I am drawn to Waskosim’s Rock again and again. It feels timeless. It’s the first place I visit when I am on the Island, and I walk there often throughout each stay. During one of those walks this past May, I encountered something I’d never seen: a box turtle, resting in the middle of the trail. These creatures can live for decades. Later, I wondered if it was the same turtle O’Neill observed on the property back in 1986. Probably not –but who knows? Thanks to the huge community effort that kept the bulldozers and backhoes and all of the other tools of development off the property, at least I get to wonder.

11 comments

11 comments

Comments (11)