A few months after our move to the island, Hardy began acting out. He wasn’t sleeping well, and his temper flared at the slightest provocation: socks were a frequent adversary, he didn’t want to get in the car and he didn’t want to get out of the car; play dates were no fun for anyone. In general, he was a pain in the ass.

Once a month a child psychologist visited the island, to check in with the various agencies and her clients. The service was free, a nod from the state not to forget about those few souls living out on the ocean; in the winter, the Vineyard has one of the highest rates of unemployment and alcoholism in the state.

We met with the woman, and she agreed to observe Hardy at preschool. A few weeks later we sat down with her again.

“He’s grieving,” she said. “He’s grieving the loss of his home in New York City. He’s moving through the stages of grief and at the moment is stuck on anger.”

This made a lot of sense, as I had come to realize that I was grieving too. I was a stay-at-home dad when we lived in New York City, which gnawed at my pride, but at least in the city there was company in the trenches. The playgrounds and parks were crowded with moms and nannies for me to chat with. I could sit with Hardy in his stroller at a café and pretend I was part of the greater world, that I was happy.

But the Vineyard was lonely and dreary in the off-season. In summer the population swells to more than 100,000, but come September the summer people begin to leave. And every week more and more people leave, so that by January the population has shrunk to about 5,000. Stores close, too, until it’s mostly just the gas stations, grocery stores, and a few restaurants with their lights still on.

It took me months to find a mom-friend on the island, and I had no idea what work I would do here. I had taken a leap of faith, following Cathlin to the place of my ancestors but now felt disconnected from my past and present. I grieved for my former life and for my future one, too. The only through-line in my life was a desire to write.

While working in banking and then the film industry, I scribbled on the side, taking classes at night and getting up early in the morning to write before heading off to work. But I had nothing to show for it, never put out into the world what I had scribbled. And what I’d written wasn’t very good, anyway. That’s not modesty: I hadn’t found what I needed to write about. And so, on the Vineyard, I turned to what was in front of me – my family.

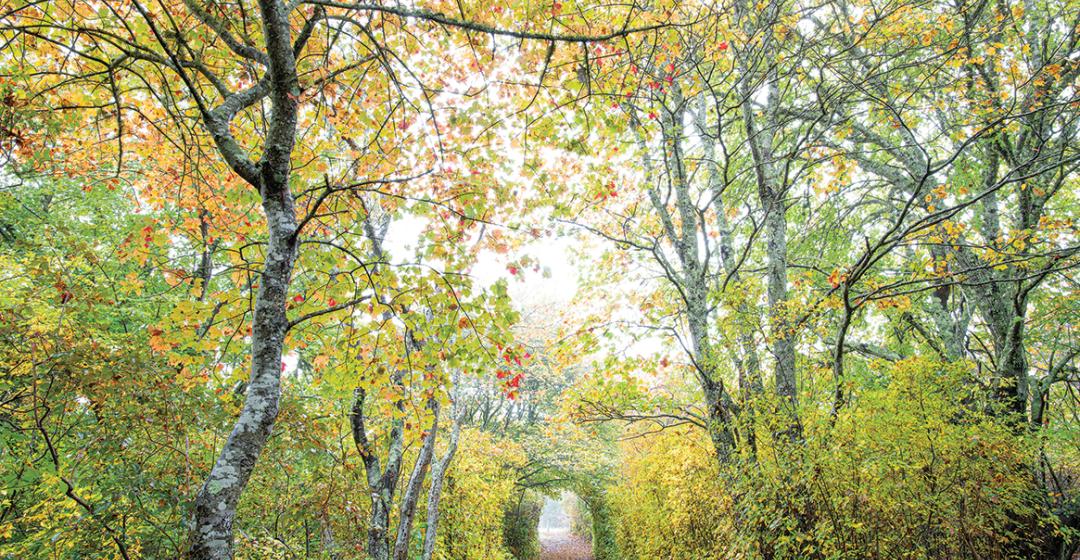

I recall taking an after-dinner stroll with our children. Hardy crashed ahead in the woods; Pickle walked closer to me but not with me, slowly becoming a small creature of the wider world rather than just something in my orbit. She walked without looking back to see if I was following. I felt a tug at my heart. My daughter has always been a bit of a mystery to me. The same is true of my son, but I do know more about the workings of a young boy, having been one myself.

I watched Pickle, a mere ten paces in front of me, but already I knew that in the blink of an eye she would travel so much farther away.

I looked out at the woods. The sun hovered just above the tree line, spreading dappled light among the leaves, burnt orange and red. I breathed deeply, then turned back to watch my daughter again. She stopped walking and looked

at me. “Dada,” she said, “will you keep me safe?”

There are times when life feels as if it’s hurtling along, a high-speed motor attached to every moment until days rush by in a blur. Everything becomes gray with motion when we go about the business of living. And then there are other moments so heavy with meaning that the earth seems to pause on its axis. This moment in the woods with my children was one of those.

There was no immediate worry. No approaching car nor overeager dog. And yet Pickle felt the need to check in, using words so loaded that my knees buckled. I ran the ten paces to her, scooped her up in my arms, and kissed her soft cheek.

“Yes, yes,” I said. “I’ll always keep you safe.”

Pickle smiled, asked to be let down, then ran ahead again. In a few steps she tripped on a root, falling to the ground and scraping her knee.

I carried Pickle into the house and took care of her cut. I wiped it clean, applied some ice and then ointment, and made the small drops of blood disappear behind a Hello Kitty adhesive.

Hardy joined us inside. At first he seemed insensitive to Pickle’s injury, going on about a squirrel he had seen in the woods while Pickle sniffled on the couch. Then he became annoying, asking me repeatedly for a cup of water.

“Can’t you see I’m busy?” I finally shouted, losing my temper.

He began to cry, but I ignored him while I continued to help Pickle, drying the tears from her eyes and wrapping her in a cozy blanket. Then I looked over at my son, sitting alone on the stairs, weeping softly to himself.

Pickle’s words echoed in my head: “Dada, will you keep me safe?”

I looked at her sitting contentedly on the couch. How quickly I had failed to keep her safe from even the most trivial of accidents, a root in her path. I looked at my son. Was I keeping him safe, letting him cry alone on the stairs?

I stood and went to Hardy, lifted him off the stairs, and brought him over to the couch. Then I sat between my children and with an arm around each, I hugged them tight, determined to keep them both safe, if only for one fleeting and fragile moment.