Captain Aaron Luce of Tisbury was livid. He was a whaler, like many of his neighbors and cousins on the Vineyard. Not much is known of his early life, but Luce had presumably worked his way up from before the mast, sailing as a ship’s boy, and rising through the ranks to boatswain, harpooner, and mate. At last, in 1842, at the age of thirty-three, he had been given command of his own whaling voyage. He was the new captain of the bark Milwood, with a crew of thirty-three and the capacity to harvest, process, and return home with as many as 3,500 barrels of whale oil. On June 25, 1842 the Milwood sailed from New Bedford – “Oil City” as the whalers called the place – headed around the horn of Africa for the Indian Ocean.

It should have been a joyous and optimistic first few days. But when they were barely out of sight of land somewhere south of the Vineyard, the disgruntled cook came to tell Luce that John Thompson, a Black man who had been hired on by the ship’s owner to serve as the steward, was uselessly seasick. What’s more, he was a “greenhand” who had never been to sea before.

There were plenty of people of color in the whaling industry, serving at all ranks, including as captain. In the 1840s, between a quarter and third of all whalers were people of color, mostly of African or Native American descent. It wasn’t therefore Thompson’s race that angered Luce. And, given that whaling was probably the worst job a free man in America could have, there were always plenty of greenhands.

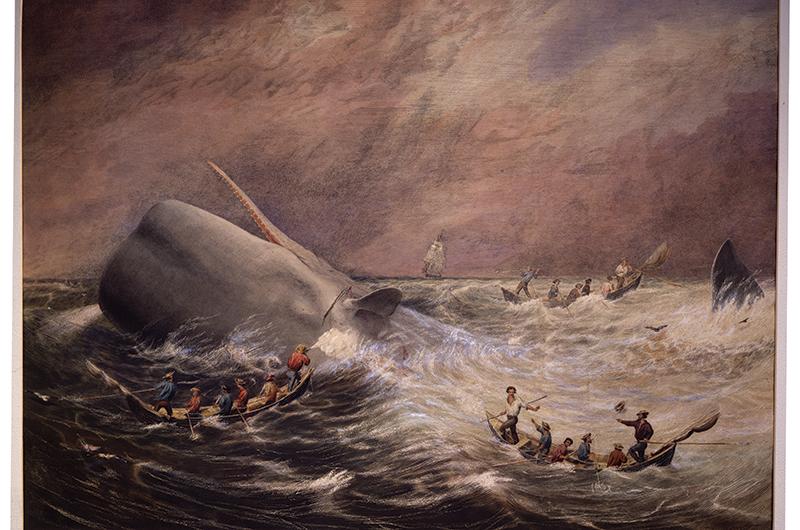

On trips that regularly lasted three to four years each, up to three dozen men lived and worked together in miserable conditions featuring boredom, inadequate clothing, disease, poor food, hellish odors, barbaric medical care, parsimonious owners, poor pay, cramped quarters, vermin infestation, and frightening weather. What was used to clean the whale grease on the deck? None other than the high ammonia content of urine, collected in communal buckets by the crew. Greenhands were common on whalers for the simple reason that they were often the only ones who would take the job, usually only once: of the 175,000 men who sailed on whaling ships over the industry’s 300-year history, it’s estimated that 90 percent only went on one voyage.

But the job of the steward, while unglamorous, was vital to the success of the voyage. The steward was the personal assistant to the captain, but his most important duty was managing the supply of food in terms of quantity and quality. This was no simple task. On a multi-year voyage there were occasional stops for resupply, but with the typical budget to feed an individual crew member only $35 per year, the quality of ingredients was seldom a priority and the menus were monotonous. (Even those enslaved on a plantation, who were traditionally supplied with seven ounces of meat and a quart or more of cornmeal per day, were arguably better fed than whalers.) But if the ship’s steward and cook allowed the food, which ranged from unpleasant to revolting, to get too bad, there was always the risk of mutiny or mass desertion.

Knowing all of this, it’s understandable that Luce was outraged to hear from the cook that the steward, Thompson, wasn’t just seasick. Plenty of seasoned sailors got sick on the first days back on the water. That Thompson had no experience at sea, let alone managing a ship’s provisions on a multi-year voyage around the horn of Africa to the Indian Ocean, was another matter entirely.

“The captain, who had been deceived by my sickness, now came into the cabin very angry, and said to me, ‘What is the matter with you?’” Thompson later recalled. “I told him I was sick.” Luce got right to the point. “Have you ever been at sea before?” he demanded.

![Around the time of Thompson’s departure, New Bedford – sometimes known as “Oil City” – was the whaling capital of the world. An 1848 painting depicts the vibrant waterfront in service of the industry. (Benjamin Russell and Caleb Pierce Purrington, The Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage ’Round the World [detail], 1848.)](https://mvmagazine.com/sites/mvmagazine/files/styles/mvg_large/public/article-assets/main-photos/2023/newharbor.jpg?itok=0SY2TpGo)

It was a tense moment, but Thompson wasn’t particularly surprised by the turn of events. The fact was he had considerably stretched the truth back in New Bedford when he convinced Gideon Allen, the owner of the Milwood, to hire him for the position in the first place. “I knew that I was wholly ignorant of a steward’s duties,” Thompson later wrote, “and consequently expected to incur the captain’s just displeasure…since at sea every man is expected to know his own duty…”

Perhaps knowing they were too far at sea to return, Thompson told Luce the truth. Other than a short voyage as a passenger from Philadelphia to New Bedford, he had not been at sea.

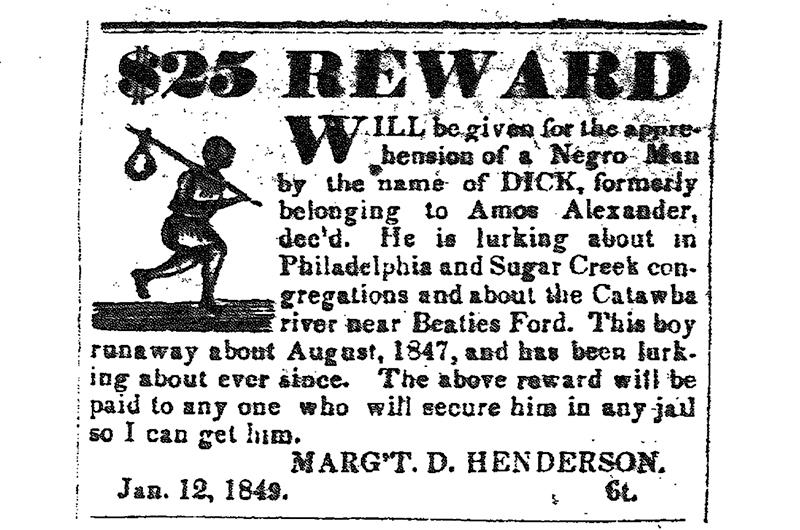

“I am a fugitive slave from Maryland, and have a family in Philadelphia,” he explained, but slave hunters were roaming that city. “Fearing to remain there any longer, I thought I would go a whaling voyage, as being the place where I stood least chance of being arrested by slave hunters. I had become somewhat experienced in cooking by working in hotels, inasmuch that I thought I could fill the place of steward.”

Luce looked at the man in front of him and informed him the usual punishment for a stunt like the one Thompson had pulled would be a flogging.

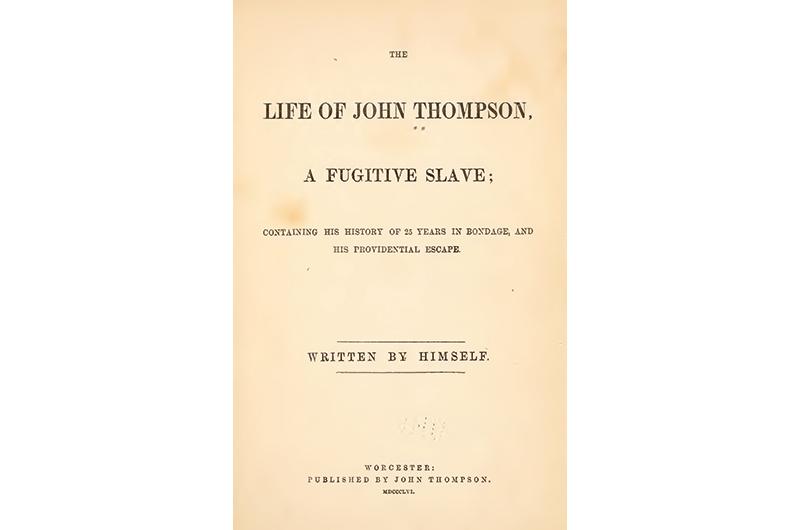

Thompson was well acquainted with the practice. In his memoir, The Life of John Thompson, a Fugitive Slave; Containing His History of 25 Years in Bondage, and His Providential Escape (Wentworth Press, 1856), he told of growing up on a plantation where his enslaver made a practice of periodically whipping workers for no reason other than “a little whipping being, as he thought, necessary, in order to secure the humble submission…” He’d seen the same man force one person to flog another, “the husband his wife; the mother her daughter; or the father his son.” He’d seen a woman die from the whipping she received for supposedly stealing a glass of rum, and an eight-year-old girl whipped for breaking a dish. He’d witnessed his own mother whipped until she could not stand. “My feelings, upon hearing her shrieks and pleadings, may better be imagined than described,” he wrote. He had himself been whipped multiple times, once to the point where he couldn’t move for five weeks.

Captain Luce showed later in the voyage that while he did not relish corporal punishment, he would, in some circumstances, order would-be deserters flogged. But he didn’t order Thompson punished. He merely told him to go up on deck and breathe the fresh sea air, and he would soon recover. Which he did.

“This narrative seemed to touch his heart,” Thompson wrote of Luce’s reaction to his story. “His countenance at once assumed a pleasing expression. Thus God stood between me and him, and worked in my defense.”

Like many enslaved people’s narratives, three quarters of Thompson’s slim memoir detail the horrors of the institution, including the floggings. Thompson was hired out by his enslaver to work for a variety of others, some of them crueler and some of them moderately kinder. At one plantation he learned to read and write, secretly assisted by one of the white children. As was common in the northern slave states, such as Maryland, many families were broken up and sold farther south. His earliest memory was of his older sister taken away in chains, bound for Alabama. Another sister escaped to freedom before he did, driven to make the dangerous move by repeated beatings for refusing the sexual advances of her enslaver’s husband.

It was the threat of his own sale that led him to eventually make a run for freedom with a friend. They encountered numerous obstacles along the way north, including tracking dogs and slave hunters, but each time they escaped – a fact Thompson attributed to numerous helpers and the “salvation of God.” Eventually, they reached the relative safety of Philadelphia, but Thompson’s companion moved on to Massachusetts after seeing his former enslaver on the street inspecting every dark-skinned person he passed. Thompson himself stayed long enough to find religion, join the Methodist church, and eventually marry. Almost miraculously, he was even reunited with his sister, who had fled to Philadelphia before him.

“Sickness and sorrow however came,” he wrote. “Several slaves near by [sic] were arrested and taken to the South, so I finally concluded best for me to go to sea.” He wasn’t alone. Roughly one in five Black whalers in the 1840s were from slave states originally, meaning, in all likelihood, they had fled bondage on “the maritime railway.” Thompson went first to New York, where he was told that the only port that would hire a greenhand such as himself was New Bedford. There he promptly went and talked his way into the job of steward of the Milwood.

As the Milwood made its way toward the Azores in the weeks following Luce’s confrontation of Thompson, the captain did more than simply forbear from punishing his steward. “The captain became as kind as a father to me,” Thompson wrote, “often going with me to the cabin, and when no one was present, teaching me to make pastries and sea messes. He had a cook book, from which I gained much valuable information.”

The rest of the crew, on the other hand, was another matter. In particular, the first mate and the cook, who had hoped to be promoted to steward when he ratted out Thompson, seemed to have it out for him. Eventually, Luce got wind that the mate had been attempting to flog Thompson when the captain was out of sight, and confronted him. The mate’s complaint wasn’t personal: it was a matter of principal that a man with no experience should be serving before the mast. Luce would have none of it, however, and, according to Thompson, “gave him to understand that he was master of the vessel, and should treat each man as he deserved, from the mate to the cook.”

Whether Luce’s attitude toward him came from a personal affection for Thompson or from having come from the Vineyard, which had a long tradition of fervent abolitionism, is hard to say. But his words to the mate appear to have stuck. Thompson reported that “After this I soon fell in favor with the mate and all the crew.” For much of the remainder of the narrative, he provided detailed descriptions of the whaling industry, from the appearance and use of the harpoon to the variety of whales from which blubber could be obtained. He also described surviving storms and scurvy, and offered a few observations of trips ashore in far-flung ports.

There are hints in the narrative, however, that Thompson and Luce’s friendship deepened during the two years at sea. Thompson’s religious faith, specifically Methodism, is a recurring theme in his memoir, and at sea he would occasionally find himself overcome with joy. He remembered “One day, while standing upon the deck, looking upon the broad expanse of waters spread out around me, and meditating upon the works of the Omnipotent and Omniscient Deity, my soul was suddenly so filled with the Holy Ghost, that I exclaimed aloud, ‘Glory to God and the Lamb forever!’”

He continued in this vein at the top of his lungs when Luce approached him and askedhim if everything was okay. “I told him my soul had caught new fire from the burning altar of God,” Thompson wrote, “until I felt happy, soul and body.”

From then on Luce, who was apparently somewhat more restrained in his spirituality, would gently tease the steward with theological questions. “The captain, being in a very pleasant mood, one day, came into the cabin, and asked me if I ever prayed for him,” Thompson recalled. He replied that he did. “Do you think that your prayer is answered?” Luce asked. “For I don’t. I don’t think they ascend higher than the foreyard.” Thompson paraphrased Ecclesiastes, telling the captain that sometimes bread cast upon the waters was found and gathered after many days.

Luce laughed, and asked if he prayed the ship would get a full load of oil. Thompson replied he prayed all the time for the general wellbeing of the Milwood and all aboard. The ship at that point had gone more than a month without seeing any whales. “He said if he had to go home without a load of oil, which he expected to do, that he should call me a hypocrite,” Thompson recalled. As luck would have it, at that very moment the lookout called “There she blows…” and three whales were taken. They were generally more successful as they continued on around the horn to South Africa, Madagascar, New Zealand, and beyond.

Nonetheless, after more than two years at sea Luce turned the ship back toward home, fifty barrels short of a full cargo. “Steward, I thought you promised us a full cargo to return with, which you see we have not got,” Luce reminded Thompson. “So I must think you a hypocrite!” Thompson replied that he was still praying, and perhaps not surprisingly given the consistent religious tenor of his memoir, the final two whales appeared two weeks later and produced 150 barrels of oil.

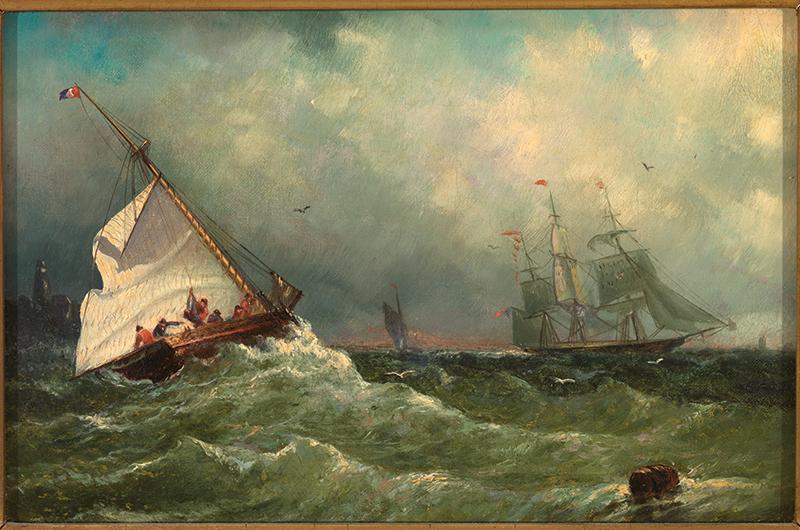

Not far from St. Helena, where they stopped to provision on the return crossing of the Atlantic, Luce learned from a passing ship that his wife, who had been pregnant when he left New Bedford, had successfully given birth. “This filled him with joy,” Thompson said, and “he ordered the mate to put the ship under all the sail which she would bear.”

“The wind blew so furiously that it sometimes seemed as if the sails must all be carried away; but like a gallant bark, the ship safely outrode the whole, and arrived at New Bedford. No pilot being in sight, we had to fire twenty rounds from the cannon as a signal, before we could raise one.” When at last a pilot boat could be seen heading their way, the crew burst into song. “But our singing was soon turned into sighing, our joy into sadness, for our pilot, being unacquainted with the New Bedford channel, could only take us in sight of the city, where we were left nearly two days to brood over our bitter disappointment.”

After the Milwood was piloted into New Bedford Harbor, wages were distributed and the crew dismissed. The unusual nature of the relationship between Thompson and Luce was punctuated when Luce and his first mate visited Thompson to say farewell just before he left New Bedford to rush back to his family in Philadelphia. Luce presented him with a bonus of $10, and the mate, who had been his nemesis at the beginning of the voyage, added another $5. Placed into digestible perspective, Thompson probably earned morethan $8,000 in today’s terms, the equivalent of an annual $4,000 salary by a man enslaved two years earlier – an enslaved person who escaped more than twenty years prior to the end of the Civil War.

Luce and the mate both asked Thompson to continue to hold them in his prayers, which, he said, “I promised to do, then bade them farewell, and left for Philadelphia.”

Other than a ship’s log of the journey that confirms the general route and weather but adds no details about the voyage, Thompson’s memoir is the only published account marking both the voyage and the friendship of two men from such very different backgrounds. Luce returned to the Vineyard to visit his wife, who was also his first cousin, and their new daughter, but was back at sea less than two months later in command of the whaling ship Herald, which left out of Fairhaven for the Indian Ocean. He returned again in 1847, but sailed again a half year later, this time for Alaska aboard the John Coggeshall, where he was the first mate and later the captain.

In all, Luce was home less than ten months of the eight years that included his Milwood voyage. Still on the Vineyard at the time of the 1860 census, at some point, like many ex-whalers, he appears to have headed to the gold fields of California. He died in his eighties in Placerville in 1895.

Even less is known of Thompson’s life after the voyage. At some point he moved from Philadelphia to Worcester, Massachusetts, where friends encouraged him to write his memoir. In his preface to the book, which was published in 1856, he noted that there had been many narratives like his already published, “but scarcely any from Maryland.”

A few years after his book was published, Thompson contracted tuberculosis. On October 3, 1859 he’s listed as the 398th death in Worcester county. It lists his age as forty-seven, the cause of death as consumption, and notes under the “sex and condition” that he was male, married, and “(colored) fugitive.” A little over a year later, Abraham Lincoln was elected president. Five months later, insurrectionists fired on Fort Sumter.

In his preface, Thompson noted the rising tide of abolitionism around him: “I am aware that now, when public opinion makes it no martyrdom to denounce slavery, there are multitudes of men that grow bold, and wield a powerful weapon against this great evil; and even school boys daringly denounce a system, the enormity of which they cannot appreciate, surely I thought it may be permitted to one who has worn the galling yoke of bondage, to say something of its pains, and something of that freedom which, if he should not succeed in accurately defining, he can truly say he will admire and love.”

11 comments

11 comments

Comments (11)