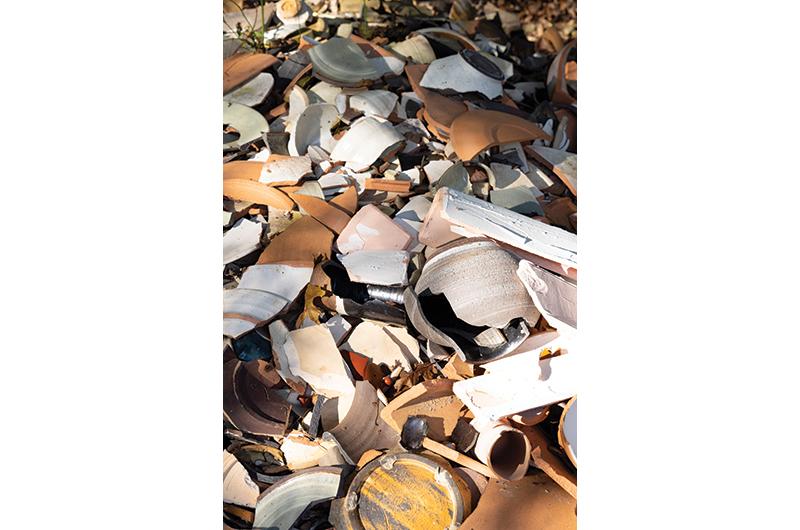

Micah Thanhauser keeps his failures in a pile at the back of his property. He has no plans to throw them away or reuse the shards of rejected pottery, but he expects the pile to grow quite a few feet taller over the years. By no means a perfectionist, the founder and owner of Merry Farm Pottery, located on Merry Farm Road, just off Beaten Path in West Tisbury, rigorously inspects each of his pieces over the course of several days. Any work that doesn’t make the cut gets smashed beyond recognition and added to the pile.

“I know of a Japanese artist who keeps his shard pile up at the front of his studio, as if to show visitors: This is what it takes,” he said. “All of this work is part of the process.”

Thanhauser isn’t looking for a specific set of criteria, but he is looking for beauty. The shape and surface of the pottery must work together, he said, to give the impression that there was no other way for the piece to be – it was determined all along. Certain flaws, such as slight warpage or an unexpected glaze pattern, are permissible if they add charm or interest to a piece, offering a kind of vulnerability to the spectator.

“A flaw shows that something happened; there’s a story there that you can see,” Thanhauser said. To him, the difference lies in whether the flaw supports a narrative or distracts.

Thanhauser’s own narrative includes growing up in West Tisbury and attending the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, where he first whetted his taste for pottery under the tutelage of art teacher Scott Campbell. After graduating in 2008, he received a degree in contemplative studies at Brown University while also taking classes at the neighboring Rhode Island School of Design. One summer in college, while back on the Island working at North Tabor Farm in Chilmark, he met Emily Flam, who was employed at nearby Mermaid Farm. The two didn’t start dating until Emily moved to Boston to attend acupuncture school while Thanhauser, now graduated, worked in Providence. After a year, they decided that they both needed a change, so they relocated to North Carolina. But the plan was always to return to the Vineyard – where Emily had spent summers – once she finished school.

That happened five years ago when he and Emily, by now married, found their current property. Formerly the home and workshop of boatbuilder and wampum artist Frank Rapoza, they saw its potential for Thanhauser’s own burgeoning business, which he named Merry Farm Pottery after the road on which they live. Since purchasing the property they’ve had two children, Asa and Mae, and adopted an Australian shepherd puppy, named Fergus, who follows Thanhauser in lockstep. Emily continues her acupuncture business in Vineyard Haven while Thanhauser works from home on his pottery.

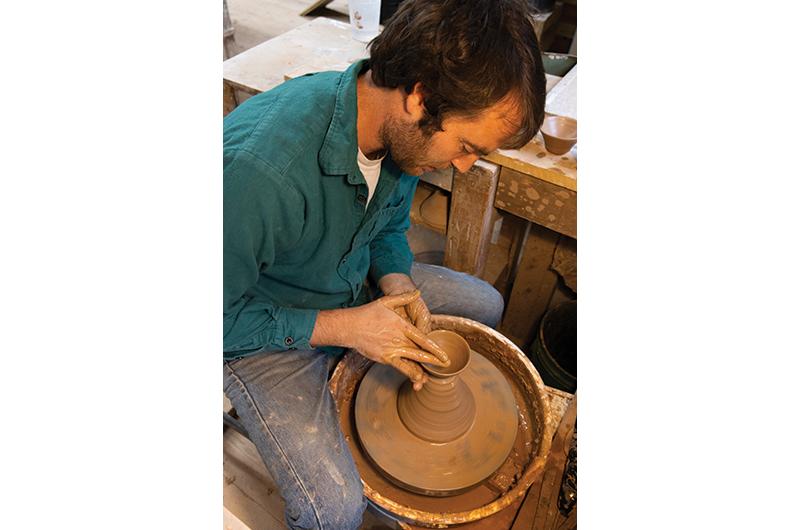

The space was perfect for Thanhauser, who benefits from living with his work, both in the sense of building a relationship with his pieces and in the literal sense. His workspace is attached to his home, a former woodshop turned studio with the addition of wheels, shelves, and a commercial kiln. Thanhauser also sells his wares in a showroom at the front of the studio, where vessels ranging from fifty to several thousand dollars sit on display racks.

“It’s a good setup to raise a family,” Thanhauser said. “When I need to, I can just go upstairs and take care of the kids. When they’re asleep, I can go downstairs and continue my work.”

Thanhauser specializes in pottery meant for food use, inspired in part by his time studying pottery during a semester abroad in Japan. To let the food take center stage, he applies minimal decoration to his pieces, limiting his palette to the clay’s natural color, a chalky white “slip” coating made from powdered clay, matte black glaze, and a clear glaze. He occasionally experiments with a glaze made from wood ash, resulting in an umbrous honey hue, which he burns and processes in his backyard.

That’s also where he keeps buckets and buckets of dirt.

Well, technically it’s clay, although in its current form it’s too raw to resemble the smooth, pliable material most people remember from art class. Most of his clay is sourced in North Carolina, using a vendor known to leave the product a little more rustic than most other commercial varieties. From there, he takes on the task of readying the clay for artistic use.

First, Thanhauser soaks the raw clay in water and passes the slurry through a window screen to remove any rocks or debris. He chooses this rustic variety because it offers him more creative control during the refinement process – the grain of the filter is up to the potter and their purposes. “That’s a very personal decision,” he remarked gravely.

If he’s feeling sculptural, Thanhauser will leave his clay rougher than usual and let the natural texture guide his work. He’s made several menorahs and candle holders using the technique, each seemingly forged by water and wind instead of the hands of a mortal artist.

Once the mixture is strained, it can take up to several months for the clay to dry enough for actual use. During that time, the clay sits in closed troughs outside the shed, beholden to the elements.

When that gets too easy, he takes his process a step further and eschews commercial clay altogether. While living in North Carolina, Thanhauser met potters who acquired local clay from wherever they could dig – usually construction sites. He brought that practice back with him, experimenting with different clays sourced directly from the Island, refining them, and learning their properties as an artistic medium. With endless construction on the Island, Thanhauser hopes to achieve a critical mass of local clay so he can continue his studies.

“I’m always looking for new clays, but it’s rare that I ever get enough to do much work with them,” he said, opening a bucket of clay taken from a construction site in Chilmark. “Right now I rely on donations from friends, but it’s nowhere near commercial quantities. By the time I’ve figured out the clay, I’m almost out. It’s a tease.”

Those same potters who use local clay in North Carolina also fire their work in wood-fired kilns, many of them hand-built. Thanhauser, inspired by his colleagues, has taken on the challenge for himself. Outside of his studio on the side of his driveway, 26,000 pounds of bricks sat waiting for use.

“It’s not a very smart business decision,” Thanhauser admitted. But the kiln is nonnegotiable – he had Islander Ethan Leite transport the bricks up from North Carolina on a tractor trailer bed before even starting his business. For four years the bricks sat unused as he grew his customer base and advanced his craft. This past October, he finally set to the task of building the kiln, which he hopes will be ready to fire by the start of summer.

He’s documented his journey on his Instagram, @merryfarmpottery, from the preliminary drawings to the final arched structure. (The technical term for the shape, he said, is a catenary arch.) The final step is building a wooden roof above the kiln to protect the oven – which can reach temperatures over 2,400 degrees – from snow or rain.

Thanhauser approached the kiln’s construction with the same material-first philosophy he carries over to all his work, letting the slight irregularities of his bricks determine the final form.

“Now it’s a more organized pile of bricks,” he said.

The process of using a wood-fired kiln, which requires constant tending over the course of several days, is more time-consuming than commercial methods and opens the medium up to new layers of unpredictability. While some artists labor toward a fixed vision, Thanhauser welcomes the whims of nature, seeing his work as a collaboration between intention and chance.

“Once you make all the choices you can make, then it’s up to the universe,” he said. “If it’s just me, I can make perfectly fine stuff. But if I’m playing a part among the dirt, the ash, the water and fire, then you get some really cool stuff.”

That playfulness has resulted in a signature style, which at first glance can look deceptively simple. Unlike more decorated pieces, Thanhauser’s designs, he said, can reveal more of themselves with regular use.

“When you’re using the same mug or the same plate every day, you might get tired of the design you were drawn to at first glance,” he explained. “But with something simpler, you start to notice the subtleties over time. You get to know the piece and build a relationship with it. It’s a lot like getting to know a person.”

Standing over the bricks a few feet away from the dense forest behind him, Thanhauser smiled and apologized – he can get wrapped up in this stuff when he’s out here. Fergus quietly munched dirt at his feet.

“You can’t let things get too easy,” he said, as if imagining the weight of the bricks on his shoulders. “There’s gotta be energy behind the pottery. That’s what makes it alive.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)