Vineyard gardens are best known for their high-summer blooms, from show-stopping roses to big, bulbous bushels of hydrangeas. But in the quieter, late months of spring, for just a few weeks each year, Fred Hancock reaps the rewards of a less-lauded flower with subtler charm.

“I’m not sure why I like iris so much,” he said one June morning on the tail end of the iris’s bloom season. “I just do.”

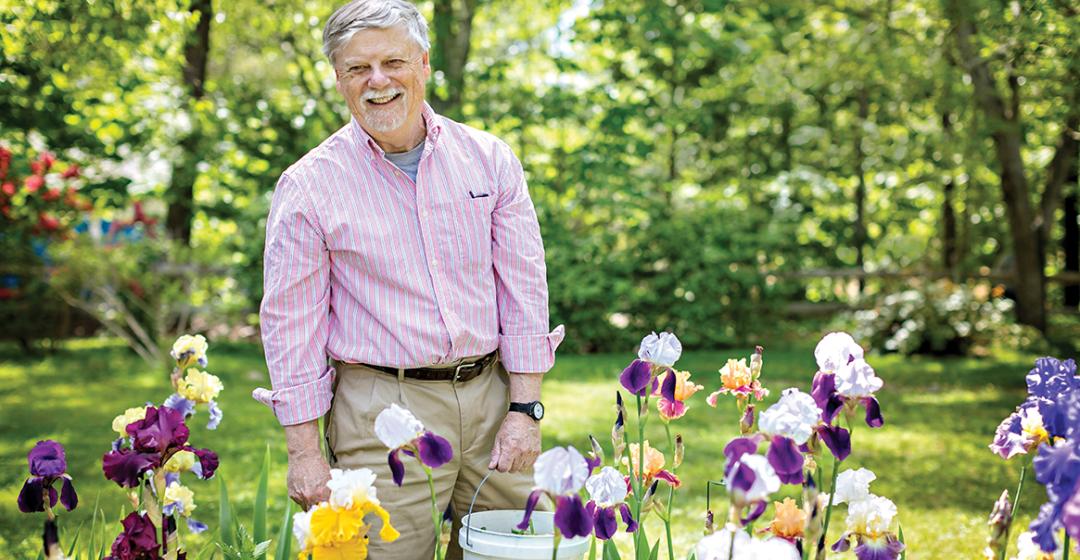

“Like” may be a bit of an understatement when it comes to his passion for the flower. All year long, he tends to his beds in pursuit of those few fleeting weeks of splendor. He’s amassed 190 different varieties (150 of which are historic) in just a few years, quickly transforming the Oak Bluffs cottage he and his wife, Kate, have lived in for almost two decades. He’s not sure when his obsession began, but one clue may lie in his former career in theatrics.

Before he turned to the iris, Hancock worked in theater. He studied lighting design and toured with the Eagles as a roadie to pay for grad school, eventually parlaying his skills into a career in product staging, supporting CEOs of major companies in their presentations to investors. In 2020, when his professional world went virtual, he decided it was a good time to retire. He’s since translocated to the Vineyard full time, where he serves on the Martha’s Vineyard Commission.

Tucked behind the East Chop Tennis Club, Hancock’s garden could pass for a performance space in itself. Each flower bed, teeming with iris, curves around a central focal point – an eight-foot giraffe sculpture named Suzanne – forming the shape of an amphitheater. The iris take the place of an audience, but they’re arguably the star.

Hancock hadn’t intended to bring his work with him. After all, he considers iris to be his retirement hobby. But to call it a hobby does some injustice. Walking around his yard, he notes which beds he wants to tear up to plant more iris. (The daisies are first on the demolition list.) He calls them “iris” instead of “irises,” which he said is a common misnomer. “I found some

of these around the neighborhood,” he said, pointing to a row of jewel-toned iris. A true collector, Hancock is always looking for new additions. “In the last three years, especially last year, I added, like, another fifty,” he said. “The year before, twenty. And I already ordered another thirty this year.”

He has started giving his overflow stock to his neighbors, and even persuaded the tennis club to let him plant a bed on their property. “I am beginning to think that I might be about at my limit of bed space,” he said, “but it is very hard to stop.”

Hancock isn’t the only enthusiast in his household. Kate collects giraffes in all shapes and sizes, including the monument in the garden. Inside the house, orange and yellow giraffes cover nearly every surface, giving the house the nickname the Giraffe Cottage. “Kate has more giraffes than I have iris,” he said. That’s no small feat.

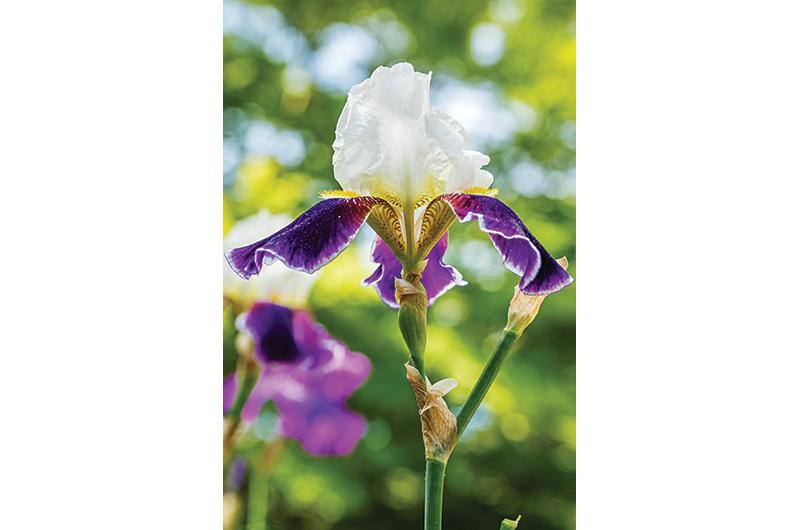

Back in the garden, Hancock’s iris collection transcends the purple and white varieties more commonly found on the Island, spanning nearly every color on the spectrum – except green, Hancock noted. The closest horticulturists have gotten is white with a slight lime-green tinge at the base.

“Iris is the Greek goddess of the rainbow,” Hancock explained, overlooking the waves of color. “That’s how iris got their name.”

While iris might not be widely known for their diversity, they are known for their exceptionally short bloom period. To love an iris is to chase the brief window between mid-May and early June, but at least the deer don’t seem to like them, Hancock said. Then, like a concert you don’t want to have end, it’s over for another season.

Although Hancock’s garden has always attracted its share of curious onlookers, at the end of last summer, it reached a new level of acclaim. Since the mid-2010s, Hancock has been a member of the Historical Iris Preservation Society (HIPS), an organization devoted to documenting and preserving historical iris varieties in home and commercial gardens. Each year, Hancock tallies his specimens and submits them to the HIPS historic iris database. Last August, he learned he had qualified to become an official HIPS display garden, one of only three in the state.

Dubbed the Giraffe Cottage Iris Garden, the collection sits alongside the Olmsted National Historic Site in Brookline and the Longfellow National Historic Site in Cambridge. It is the only private residence in the state to receive the distinction.

To be named a display garden, the collection must identify at least fifteen different varieties of iris and be open to the public for some period of time during blooming season. HIPS currently lists forty-seven display gardens across the country and as far away as Czechoslovakia.

Even in fame, Hancock is self-effacing about the whole thing. “It is a pretty low bar,” he said. Still, with his garden of 150 historic iris species, it’s a bar Hancock has surpassed tenfold.

To show off the new designation, Hancock received a sign, which he’ll put up this spring when his garden, located at 31 Dudley Avenue, opens to the public. There are no formal hours, but he welcomes any curious passersby. In the meantime, he’ll continue attending regular Zoom meetings with HIPS members, sharing iris knowledge with gardeners across the globe. “There are some real eccentric characters over there,” he said with a smile. “Much more eccentric than me.”

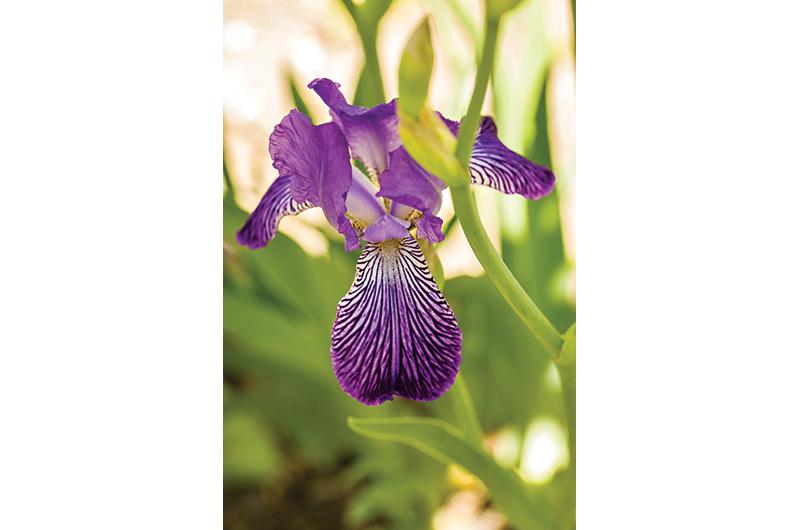

When it comes to iris identification, the American Iris Society is responsible for assigning the names to the various varieties. However, the distinction between varieties can be almost imperceptible, only observable in certain seasons, lighting, or conditions. The flower is made up of three standards (the petals raised upward), three falls (the petals pointed downward), a “style arm” (the flourish in the middle), “style crest” (the flared end of each style arm), and sometimes a signal (the pop of color that runs down a fall).

To illustrate the difficulty, he shows two near-identical iris. Both varieties have crimson-red standards and falls with a deep yellow signal. The difference, Hancock said, lies in the streak of yellow in the foliage of one of the flowers, near the base of the rhizome. “If I didn’t label them all, I would never get them all straight,” he said.

Much like the Dutch and their tulip market, the French began toying with iris genetics in the late 1800s, following the popularity of Gregor Mendel’s famous pea plant experiments. The chance to play God led to thousands of different iris varieties, although the market never took off like the tulip market did.

“The famous symbol of France, the fleur-de-lis, is actually based on an iris,” Hancock said.

Centuries later, the chance to put one’s name on a brand-new iris variety has not lost its luster, Hancock said, as breeders introduce new iris varieties every year. Like most fervent thrusts toward innovation, the demand for never-before-seen iris has had unintended consequences. As new iris come into fashion, Hancock explained, older varieties have fallen by the wayside without a concerted effort to keep them from extinction.

It’s not that Hancock doesn’t like newer iris – he keeps a few at the front of the property – but he generally finds them a bit too flashy for his taste. One of the defining features of a contemporary iris, Hancock said, is their size. More recent stocks of iris can reach up to four feet tall, with blooms practically the size of your hand. Additionally, many contemporary iris sport unconventional features from ruffled, almost feathery petals to pearlescent sheens. Hancock identifies one such specimen whose standard petals shine a nature-defying metallic silver.

“There’s nothing wrong with it,” he said, cupping the iris’s frilly head in his hand. “I just like the traditional form a bit better.”

Despite his involvement in HIPS and his recent accolade, Hancock isn’t on a mission to save the iris. He only plants what he likes, and he won’t choose favorites either. When pressed, however, he will point out a couple varieties nearest to his heart. Two native iris, the Cape Cod and the Gay Head, used to grow in the sands of their namesakes. Both flowers stand on the smaller side at a little over fifteen inches tall, especially compared to the elephantine newer varieties, and share yellow-ochre petals with dark purple signals.

They were both bred by a man named Harold Knowlton, Hancock explained, a Newton resident who had visited the Island. A committed fan, Hancock wanted to visit Knowlton’s other property in Lowell to see if there were any examples of his iris in the neighborhood, but discovered that the MassPike and a housing development have been built in its location.

When left alone, iris reproduce asexually, leaving their traits unchanged. The oldest variety in Hancock’s garden dates to 1756, when Linnaeus included the flower in his exploration logs. That iris, called sambucina, originated on the Dalmatian coast and the steppes of central Asia. It resembles most of the blue-and-yellow iris found in gardens today. “Its name means elderberry in Italian,” he said. “It’s supposed to smell like elderberries, but I have no idea what the hell elderberries smell like.

“Many people use iris as family heirlooms, growing the same iris that their great-grandmother grew. It’s like owning a piece of history,” he added. “A living piece of history.”

When wanderers cross Hancock’s path this April and May, they’ll be privy to the same surprise he enjoys every year, when the new bulbs he ordered months ago finally come into bloom.

“It is like opening presents every year to see the ones I’ve never seen,” he explained in a season-end update, months after the garden tour. “Even though I have pictures, there is usually something about them that is not really captured.”

After the blooms have gone and the iris return to the ground, Hancock will begin the process all over again. In July, he’ll scour the internet for more iris varieties, and the daisies might really have to go to make room. In December, he will shield his iris bulbs from the bitter cold with the boughs of retired Christmas trees. In the first week of March, he will uncover the bulbs for signs of shoots and later follow with fertilizer.

Every couple of months reveals a new stage in the life cycle of the iris, otherwise a mystery when observed above ground. Hancock keeps a log of his progress and is more than happy to share what he’s found, if anyone were to ask.

They may not. Hancock knows many are content just to admire his garden, or plant a few iris species in their own yards without becoming experts on the subject. But hope, much like iris, springs perennial, and his exuberance streams out in paragraphs, punctuated by a characteristically self-deprecating nod: “That is most likely more,” he concluded, “than you really wanted to know.”

Iris 101

It doesn’t take much effort to reap the fleeting rewards of iris, especially on the Vineyard. The flowers grow best in sandy soil, of which the Island has plenty, said Fred Hancock. And unlike thirsty hydrangeas, iris thrive on benevolent neglect, their main enemy being overwatering.

In the quiet off-season months, which the Vineyard also has plenty of, Hancock plans his expansions. “I typically buy bulbs in the summertime and plant them immediately before they dry out,” he said. He shields his bulbs from the cold with the boughs of Christmas trees, which allow them to breathe.

Iris bloom season begins in early May and peaks around Memorial Day, preempting the summer rush. As for what he does then, Hancock said: “I just sit back and enjoy them.”

Some regular maintenance is required, however, to produce a thriving display. If left to their own devices, iris – a rhizome like ginger or canna lily – will split and grow offshoots until the main bulb overextends and can no longer bloom. To prevent an uneven, overgrown garden, Hancock breaks up his iris by the root, segmenting the central rhizome and scattering them to form their own families. The sheer volume of ever-multiplying iris at his disposal means he shares the wealth when and where he can. “I try to give them to my neighbors,” said Hancock, “or sometimes we’ll host iris parties to share them with the neighborhood and get new varieties.”

5 comments

5 comments

Comments (5)