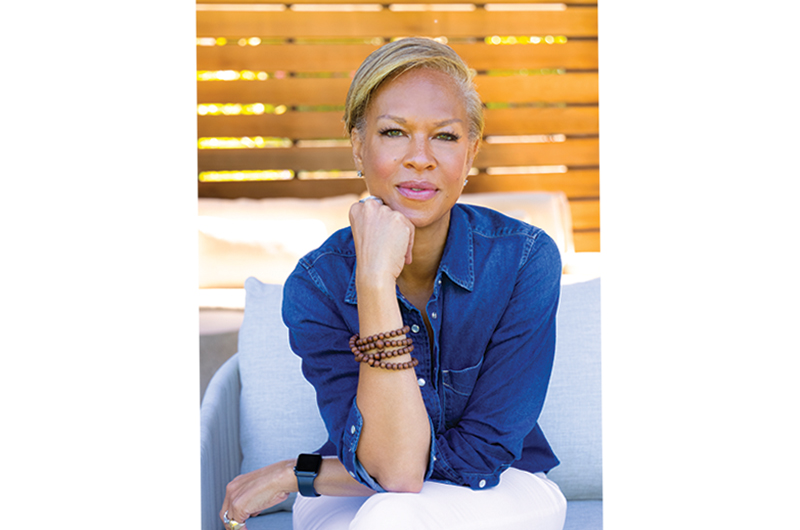

Like many who land on the Vineyard, author, advocate, producer, and filmmaker Tonya Lewis Lee was introduced to the Island by a significant person in her life. Unlike the rest of us, for Lewis Lee that person was Academy Award–winning screenwriter, director, and longtime Vineyard resident Spike Lee.

For more than twenty-five years, the couple and their two children have kept a home in Oak Bluffs, enjoying the Island both as a place to escape the hustle of city life and, increasingly, as a venue for sharing meaningful professional projects. Lewis Lee’s most recent film, Aftershock, which screened at the Martha’s Vineyard African-American Film Festival this past summer, is a powerful look at the Black maternal health crisis and the tragic consequences of disparities in care and treatment. Here, she talks to Martha’s Vineyard Magazine about the evolution of her work as an artist and advocate, the responsibilities of a creative life, and the shifting rhythms of her Island routine.

MVM: Tell us your Vineyard story. You’ve called New York home for much of your life. What first brought you to the Island?

Tonya Lewis Lee: I was born in Yonkers. My father worked for a corporation, so we moved around a lot. It was my husband, Spike, who brought me to the Island. He tells this story of how he came one summer in college with a classmate who had invited him to stay. Right away he said: “If I ever get any money, I’m gonna buy a place up here.” After Do the Right Thing he started building a house and it was finished in 1992, which was also when we met.

MVM: After college and law school, you worked in corporate law before transitioning to a career in television production. How did that move come about?

TLL: When I was graduating, I wanted to go into TV, but I didn’t know anybody in television and my family was like: “You want to do what?” So I thought, “If I’m going to be a lawyer, I’ll be a civil rights lawyer; at least then I’ll be helping people.”

I got to law school and I did clerk for the NAACP, but by then I understood that I could make real money at a corporate law firm. I was still doing the pro bono thing, but I knew that the corporate firm was not going to be a long-term situation.

I’d always been a writer, just for myself, and when Spike and I got together he was very supportive of me finding my own creative life.

MVM: You and your family were recipients this spring of the Gordon Parks Foundation Award for your commitment to social justice in the arts. Representation and advocacy has been at the forefront of your work, whether in the children’s books you’ve written, television programming, or films. Do you believe artists have a responsibility to address issues of injustice?

TLL: We do have a responsibility as artists. It doesn’t have to always be on the nose, but when you are telling stories that are truly based in humanity, that has to come through. I believe that storytelling is how we understand who we are in the world. You help people to see what can be; you remind people that we’re all connected.

MVM: Your film Aftershock tells the stories of two Black men who lost their partners due to preventable complications during pregnancy and childbirth. How did you become interested in the issue of maternal health and morbidity in people of color?

TLL: I came to the issue in 2007, when the Department of Health and Human Services asked me to be a spokesperson for infant mortality. Over time I realized when we were talking about infant health, we were really talking about women’s health. In my travels around the country, I had the privilege of being able to go to all sorts of communities. I talked to groups of women and stakeholders, and I was inevitably hearing about the maternal mortality rate, which was starting to tick up.

In 2017 or ’18 there were a couple of big articles in The New York Times and ProPublica about this crisis – the inequity and disparity that existed in maternal health, and how it was getting worse. I thought, “If I’m going to do this I need to focus and find the right partners.” I knew I needed to have the right team.

[Co-director and -producer] Paula Eiselt and I met in the fall of 2019 at a women’s conference. We were both filmmakers and passionate about maternal health and we decided to put our forces together.

MVM: Aftershock shows how a subject commonly viewed as a “women’s issue” can have a lasting impact on entire communities. How did the narrative take shape?

TLL: Maternal health is a community health issue. Partners and families are left behind. That was the thing about [film subject] Shamony Gibson; her community was devastated by her loss. When Shamony died in October of 2019, her partner Omari [Maynard] and her mother, Shawnee [Benton Gibson] – who is a reproductive justice advocate – wanted to have a celebration of her life and a conversation about maternal health, and they put out an invitation on social media. We reached out to her and asked if we could come film.

Omari had also put out that he was going to host a men’s circle, so that other men who had lost partners could come and talk and be vulnerable with each other and support one another. And that’s how it all started. When we filmed and saw the group of men it became clear that Omari was somebody we wanted to follow.

MVM: What does the Island mean to you?

TLL: I love the Vineyard. I’ve spent more time here in the last couple of years because of the pandemic. This is our homestead; this is where we come for summers, for Thanksgiving. It’s a place where I have a chance to relax, to go inward.

This August, it was a lot! As more people come with a desire to see each other, it’s wonderful, but I’m trying to hold on to that sacredness of just being here.

As I look back through stages and phases of life – first we were newlyweds coming here, then coming with our kids, and now the kids are older – it’s always becoming something else. Now I look forward to my old age here. Often I run along [Beach Road] towards Jaws bridge. I’m still doing it, and I want to still be doing it in my seventies. And if I’m not running it, I’ll be walking it.