Anna Cotton didn’t set out to create a wildlife sanctuary. Nor did she want to landscape her garden to the hilt, filling it with expensive and difficult-to-maintain ornamental plants. More than a decade after moving to a small plot off Franklin Avenue in Vineyard Haven, she had barely done any landscaping. Her yard was neglected and overgrown.

That was just fine by her. A science teacher at the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School with two young kids of her own, she and her husband, Damon Runyon, had their hands full – and the yard full of kids’ toys to prove it. But as construction projects began to proliferate on their once-quiet street, Cotton noticed an increase in rabbits in her yard. They had been chased out, she suspected, from a nearby vacant lot due to construction.

Their appearance made Cotton wonder what other creatures had been affected by the construction and fragmentation of their natural habitat. And she wondered what she could do to help.

That’s where Angela Luckey came in.

Luckey, who was born and raised on the Vineyard, is an expert in native plants: those species that have co-evolved with local fauna over thousands of years and therefore pose unique benefits to wildlife. For the past year and a half, she’s also been the program director of Natural Neighbors, a free program that, with assistance from other experts, helps homeowners transition their properties from unintentional ecological dead zones into biodiverse havens using native plants and creative gardening practices.

The program is sponsored by a two-year grant from the Martha’s Vineyard Vision Fellowship, which gives financial support to individuals and organizations looking to continue their studies or develop projects that benefit the Island community.

“I’m not there to judge what people are doing,” said Luckey, who has a bachelor’s degree in plant, soil, and insect sciences from the University of Massachusetts and a master’s in environmental management and policy from American Public University in West Virginia. Instead, she arrives at each client’s home eager to discover possibilities, and to offer guidance compatible with the homeowners’ wishes. Her goal is to create a landscaping program that’s not only beneficial, but also visually appealing and easy to maintain.

“Let’s uncover what’s really exciting about the property,” she said, pushing her hair over her shoulder. “How can they promote more biodiversity?”

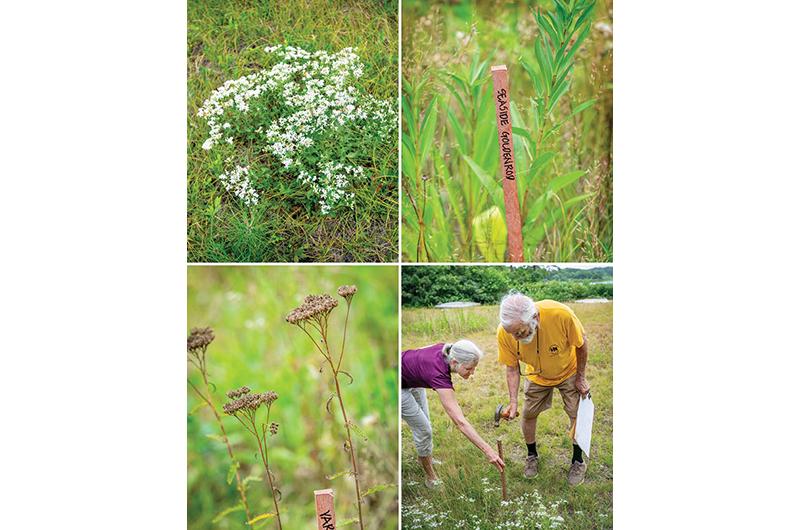

In the first year of the Natural Neighbors program, Luckey worked with about 115 Vineyard homeowners. But her dreams are even bigger: she ultimately hopes the program can transform at least 10 percent of the Island’s residential properties into more ecologically balanced spaces. To that end, she presented Cotton with a ten-page plan, advising her in part to use a light hand and let nature take its course. Don’t rake up your leaves and tidy your garden, she suggested. Instead, leave the organic matter to decompose, supporting

worms and insects, and leaving seeds for birds. Leaf litter also provides a valuable habitat in which butterflies and moths can safely complete their life cycle.

That pile of brush Cotton kept meaning to clean up? Don’t bother. It’s valuable stuff.

“Lawns can be fun for a picnic or a [game of] catch,” said Luckey. But, she said, property owners who are concerned about the environmental well-being of the Island might want to take stock of how much lawn they really use and need. “Do they need to be so big?” she asked. “Can a property maintain a smaller lawn next to a meadow or other habitat-friendly feature?” And perhaps, most important, can the lawns that homeowners do feel they need be planted with native, drought-resistant grasses that require minimal fertilizer and maintenance?

The idea for Luckey’s Natural Neighbors program grew out of a collaboration with fellow environmental scientists Tom Chase of the Village and Wilderness Project, a nonprofit incubator for climate adaptation strategies; and Luanne Johnson of BiodiversityWorks, a conservation organization focused on wildlife monitoring and research across Martha’s Vineyard. (Luckey is an employee of BiodiversityWorks, and the Natural Neighbors program exists under its banner.)

As Natural Neighbors’ reach has expanded, Luckey has learned to walk a mile – more or less – in her clients’ gardening boots. The process requires diplomacy, something she learned from Chase. Before she started working with clients, Chase helped her evaluate and redesign her own family’s property, surrounded by woods and wetlands, in West Tisbury.

One of their first moves was to install a little pond. The rewards came quickly. Not only was the pond a sweet addition to the yard, but three weeks after filling it up, she discovered pickerel frogs enjoying a cool bath and snakes hanging out nearby. Both kinds of critters provide excellent pest control.

“You don’t have to do everything at once,” she said.

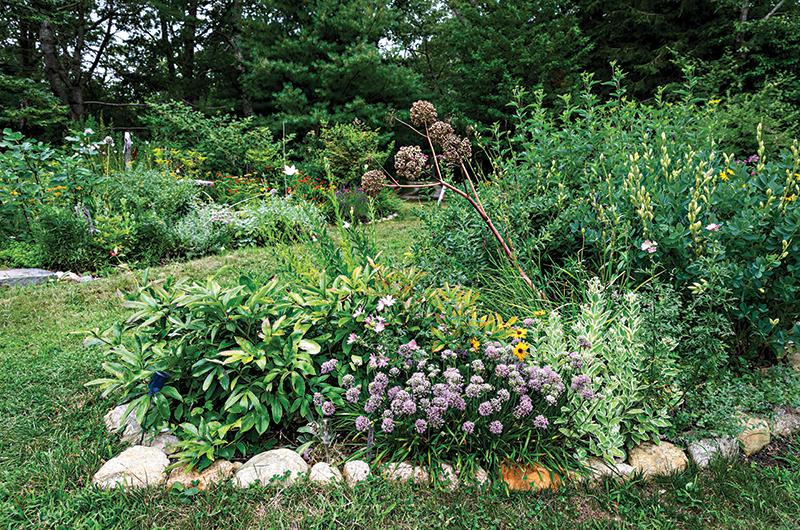

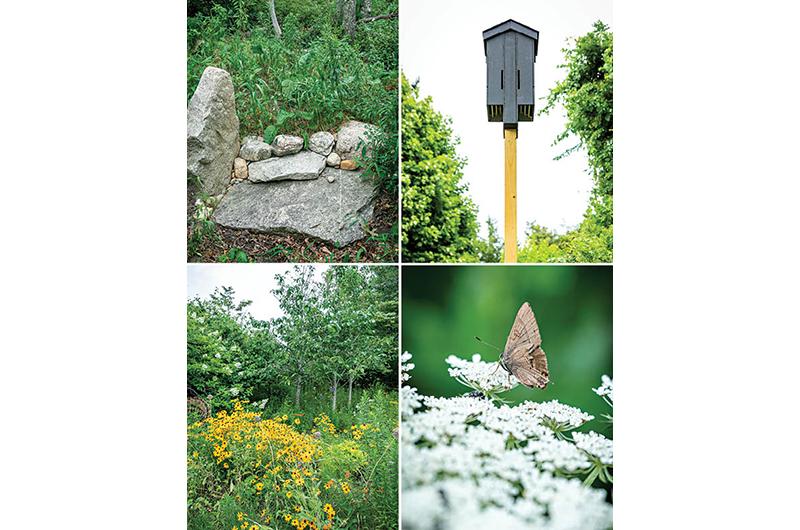

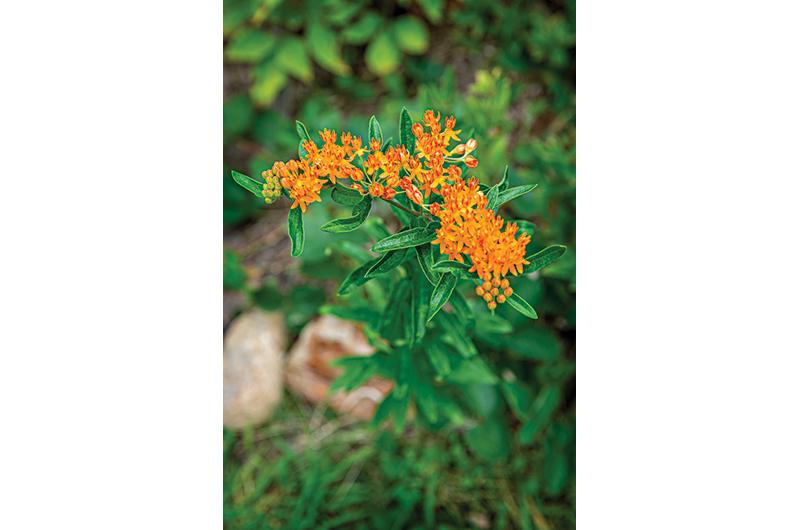

Over time, Luckey has increased her own garden’s native plant diversity with perennials and shrubs from local nurseries, marveling at how they attract bees and butterflies and moths, which in turn feed birds. Goldenrod and aster, sassafras and shadbush, butterfly weed and switchgrass – there are so many great choices, she said. But you don’t have to go overboard. If you can populate your yard with about 70 percent native plants, you’ve done the job. Then you can play around with other features – nest boxes, bat houses, snake boards, stone walls, perennial-shrub-canopy layers, all of which offer places animals can hide from predators and create nests.

Even brush piles can be an asset. Last winter, Luckey checked the brush pile near her house and found chickadees hiding from a hawk.

Walking through her yard now is like a treasure hunt, she said: “We never know what we will discover.”

In addition to consulting with individual homeowners, Luckey offers occasional workshops at libraries, garden clubs, and schools. She hopes that with support from homeowners and renters, the program can survive beyond the two-year grant, which ends in May of 2023, and become a model for other communities. She is also seeking additional grant and donor support in hopes of broadening the scope of the program to help homeowners remove invasive species. “Just letting a realtor or landlord know that you support a natural landscape can help this movement grow,” she said.

Anyone who has their doubts about the program’s benefits need only speak to Cotton, who Luckey credits with transforming her untended yard into an appealing, easily maintained landscape.

Doing so required making some difficult decisions, though. The idea behind Natural Neighbors is that best should never be the enemy of better. And that people are part of the planet too, and just need guidance on how to tread softly. So they cut down a white pine to provide light for the vegetable garden, for instance. But they opted not to cut down an oak for aesthetic as well as practical reasons. Not only was the tree beautiful; it removes carbon from the atmosphere and retains water especially well, meaning it doesn’t need to be watered as often as a non-native ornamental tree might.

And since Cotton wanted to preserve some of her home’s privacy with all the construction going on around her, she and Luckey met with some of the new neighbors and agreed to work together, planting shrubs along the border of their properties to shield the noise.

Never much of a gardener before, Cotton admits she’s been surprised by how much she appreciates her newly planted border of American holly saplings, courtesy of Polly Hill Arboretum in West Tisbury, and the mini sanctuary Luckey helped her create to draw birds and pollinators, as well as all manner of bugs that form the basis of the food chain.

“She makes the whole process easier,” said Cotton. “I’m now measuring the beauty of my yard by how many birds I hear.”

Pollinator-Friendly Native Plants Recommendations

Looking to make your backyard more hospitable to wildlife? Prioritizing native plants – those that have evolved in their environments for thousands, if not millions, of years – over conventional lawns is one of the simplest steps you can take, said Angela Luckey, who runs the Natural Neighbors program under the banner of BiodiversityWorks.

“Generally, a few hundred years is not long enough for introduced plants to be functional within an ecosystem, as wildlife has not developed the adaptations to use those plants as food sources,” she explained. “These relationships can be highly specialized, like bee specialists requiring specific flowering plants to collect pollen from, or butterfly and moth species requiring specific host plants for their larvae (caterpillars) to feed from. The berries and nuts of native plants are also more nutritious for bird species.”

Conventional lawns, by contrast, are not equipped to provide habitat, food sources, or other services to the flora and fauna around them. Plus, they often require additional watering and fertilizers to maintain their appearance.

Fortunately, the Island has supported a diverse array of native plants for eons. Consider some of the options Luckey recommends below.

Trees

Oaks – white, black, post, scrub, dwarf chinquapin

Birch – Betula

Eastern red cedar – Juniperus virginiana

Pitch pine – Pinus rigida

American holly – Ilex opaca

Shrubs

Blueberry – Vaccinium angustifolium

Beach plum – Prunus maritima

Hazelnut – Corylus americana

Winterberry and Inkberry – Ilex verticillata and Ilex glabra

Arrowwood – Viburnum dentatum

Spicebush – Lindera benzoin

Chokeberry – Aronia melanocarpa

Serviceberry / Shadbush – Amelanchier

Willow – Salix

Witch hazel – Hamamelis virginiana

Perennials

Bearberry – Arctostaphylos uva-ursi

Swamp milkweed – Asclepias incarnata

Pearly everlasting – Anaphalis margaritacea

Coastal Joe Pye weed – Eutrochium dubium

Tall white aster – Doellingeria umbellata

Goldenrod – Solidago or Euthamia

Hyssop-leaved thoroughwort – Eupatorium hyssopifolium

White wood aster – Eurybia divaricata

Butterfly weed – Asclepias tuberosa

Grasses

Switchgrass – Panicum virgatum

Little bluestem – Schizachyrium scoparium

Wavy hair grass – Deschampsia flexuosa

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)