The autumnal equinox and a strong moon were upon us. Prime time to find an Atlantic bonito. A day ago, someone on Lobsterville Beach caught a real monster, a thirteen-pounder. You had to love it. So that is right where my son and I now stood. We deserved a big bonito too. Didn’t we?

With fire in our eyes, we chucked flies into an aquamarine sea. After several hours slipped by without any sign of life, our hopes were ebbing fast, much like the tide. We had been squelching the idea of calling it quits. Nobody wants to get skunked. Still, the dice had been cast. Reluctantly, we reeled up and wandered to the truck, singing the bonito blues.

Hardcore anglers harbor strong feelings for fish – although admittedly, we get mighty picky. We are passionate about some and not so much about others. It is fair to say striped bass are the most loved fish on the coast. Searching for bass becomes a lifelong passion. It lives in your blood; visions of fifty-pounders dance in your dreams. Yes sir, fishing for striped bass can take on mythical meaning.

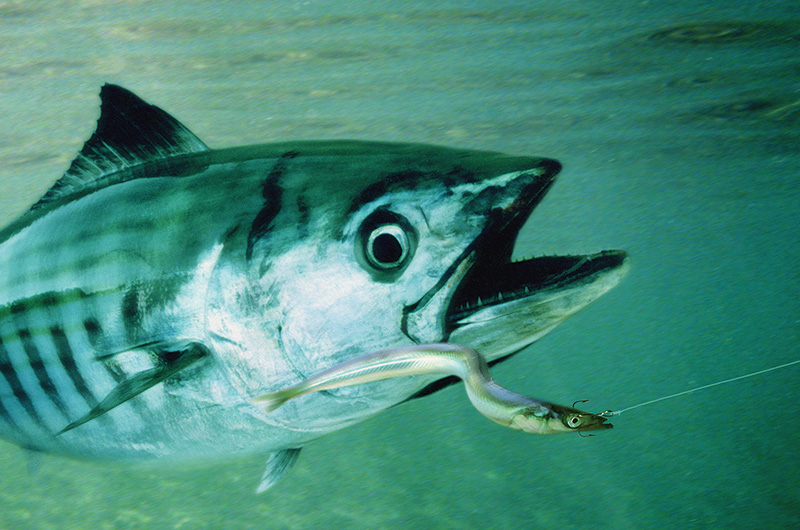

But I’m fascinated with Atlantic bonito too. And I’m not alone. Call them “greenies,” call them “bones,” call them what you wish, bonito have a fervent following among light-tackle anglers. It’s easy to see why. Bonito are beautiful and elusive creatures. Along with the rest of the tuna tribe and mackerels, they are in the Scombridae family – some of the most powerful fish on earth. On the end of the rod, they instantly earn your respect: ripping off line, running erratically, disappearing deep at the drop of a hat. Always, always testing your skill.

Granted, nonanglers may never understand – but they should. Animals are our only living, breathing partners on this planet. It’s little wonder that our desire to connect with them springs from the deepest parts of our psyche. We want to experience them, learn their lives, and share their wisdom. Every culture since the beginning of time has done it, wrapping wildlife in legends, myths, and magic. Witness it in the cave paintings done by Neanderthals more than 40,000 years ago. See it in the cat-headed deities of ancient Egypt. All twelve Greek gods of Olympus are associated with animals. Every night, they ride overhead in the names of constellations.

My love of Atlantic bonito was born on a September day long ago. After rowing out of a small estuary, I worked a fly near a rock island, a spot bonito liked. In time I hooked and landed one, but this bonito made me do a double-take. Still, there was no denying what it was. Residing in my hand, perfect in every detail, glowing emerald and silver in the sun, was a baby bonito eight inches long. The first I had ever seen.

My curiosity peaked, I dug deeper, learning that young-of-the-year bonito grow an inch a week. Rudimentary math revealed my tiny tuna had been born in July. Bingo – something clicked. The first bonito of the year always behaved oddly. They might show up as early as mid-June, staying away from land and never being very aggressive. Then they would vanish for weeks, reappearing in late July, moving closer to shore and feeding with abandon. Now I understood: they had been spawning offshore, their progeny drifting back toward land on the southwest winds of summer.

In the intervening years, I’ve caught bonito here and there, but never many in a single day. For one thing, they are hard to find, especially in numbers. And when you find them, they are always in high gear. Here and gone in a flash. Or worse yet, they hang tantalizingly just outside of flyrod range. Maddening. Even when you get one to strike, there is no guarantee you’ll land it. There are not many soft spots to park a hook in an Atlantic bonito’s mouth, fewer than a bass or a false albacore. Adding to the dilemma, the bonito is a “ram ventilator” – it can breathe only by swimming forward with its jaws open. When one races line off your reel, there is a chance the hook will fall free.

The finest fishing for bonito occurs in the fall. To predict how long it will last, however, you best consult a clairvoyant. There’s no question the forces driving migratory fish are manifold. Years ago, Russell Chatham put it this way: “To understand the salmon, it has been said, would be to crack the universe.” His point is well taken. The sun and moon, forage, wind, and weather all figure into the equation.

From my years on the water, however, I can tell you this: bonito can hang much later in the fall than most anglers realize. One freezing November morning, I took a boat ride out to Watch Hill Lighthouse on the Rhode Island coast. A few fish were breaking on the east side of the light. I assumed they were striped bass. After busting the ice out of my rod guides, I hooked and landed an Atlantic bonito. Surprise, surprise. The water temperature? About 50 degrees. Think about it: mid-June to mid-November. As scarce as bonito seem, they may be in the Northeast nearly six months each year.

Besides pondering when bonito come and go, anglers wonder how many bonito will show in the upcoming season. From year to year, abundance can vary vastly. There may be many. There may be few. They may be mainly small ones. Or they may be large. Your guess is as good as mine. No doubt it depends on the size of the bonito population. Still, there are other factors. If false albacore arrive in force, bonito typically disappear. And I’m convinced in some years bonito simply elect to feed more offshore than inshore, giving the impression that their numbers are down. On the other hand, some people will tell you bonito are no longer as plentiful as in the good old days. There is reason to believe it’s true. In 1945, 57,000 pounds of bonito were brought to market on Martha’s Vineyard. Those numbers are inconceivable now.

On top of all that mayhem, there is a wild card – global warming. Martha’s Vineyard and Cape Cod have long been seen as the northern extent of the bonito’s range. Right now, however, the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 99 percent of the ocean. In recent years, juvenile bonito were caught on the coast of Maine. Does that mean the bonito population is expanding? Or does it mean Atlantic bonito are just moving farther north? Time will tell.

Regardless, my flyrod is at the ready, my fly boxes full. I don’t want to be caught singing the bonito blues. Wish me luck.