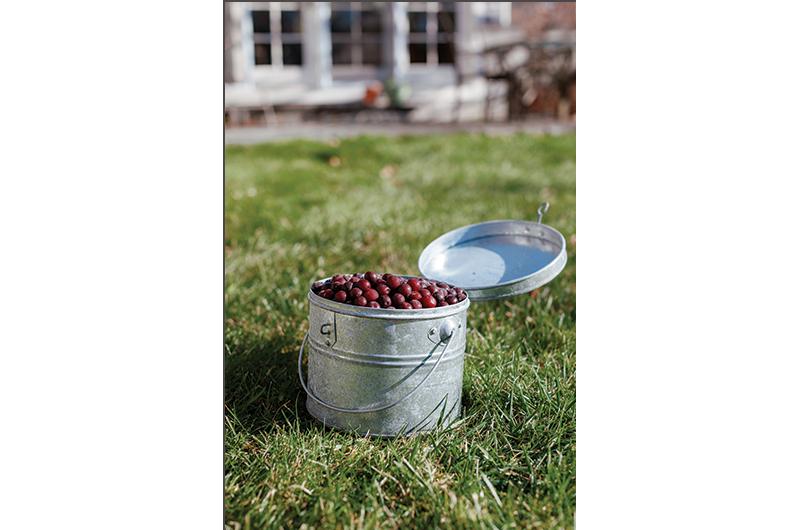

Last fall, wild edible fruits grew so abundantly that people literally dropped off buckets and boxes of beach plums – the bluish-purple fruit that grow on seaside bushes – on our porch. A friend with beach plum bushes on her property said she couldn’t keep up with picking and asked if I would please help. Around the same time, the small red berries called autumn olives hung in clusters on trees by the thousands.

This was all very unusual, especially for prized beach plums. In a typical year, someone might show you a bucket of just-picked plums but not reveal his or her cherished picking spot – and they almost certainly wouldn’t give them away.

The size of large marbles, beach plums have been an Island resource for thousands of years, first appreciated by the ancestors of today’s Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) along with blueberries, blackberries, grapes, and cranberries. Kristina Hook-Leslie, a Wampanoag tribal member, once recalled to me that each fall on traditional picking days, grandmothers, aunts, mothers, and children would head to the dunes between Menemsha Pond and Lobsterville Beach to pick from the beach plum bushes.

Today, interest in the beach plum remains unchanged. They’re particularly welcomed by full-season foragers as they ripen in late summer and early fall, when the Island’s plentiful blueberries and blackberries have stopped fruiting. A relative of the domesticated plum, wild beach plums (Prunus maritima) boast similarities with the grocery store variety – both have a single pit and reddish, tart flesh. They’re also good for your health, loaded with vitamins A, C, and K, and are a good source of potassium and fiber. But the wild beach plum is much more tart, making it unpalatable to eat plain. Today’s pickers enjoy them most often in the form of beach plum jams and jellies.

Autumn olives (Elaeagnus umbellata)also fall in the more-tart-than-sweet range and ripen in early fall, though unlike the beach plum they can be enjoyed without embellishment. The small silver-leafed trees on which they grow were introduced from Asia in 1830. In the 1950s and ’60s, they were planted along highways as part of beautification projects, and soon spread widely as an “invasive” crop. But while autumn olives draw the ire of some for their ability to crowd out native plants, they have plenty of admirers too. Sometimes called an invasive superfood, they are an excellent source of lycopene, as well as Beta-carotene and Vitamin C. Locavore chefs often turn them into preserves, jams, jellies, or purée for sauces.

I first started picking autumn olives years ago with my son who loved the slightly puckering flavor of the autumn-olive fruit leather we made. As he grew older, we outgrew fruit leather and I began making cordials and liqueurs with both beach plums and autumn olives.

Making liqueurs and cordials used to be a more common method of preservation. Cordials were first produced in Italian apothecaries during the Renaissance using alcohol, herbs, and spices primarily for medicinal purposes. Around the same period, European monasteries were producing liqueurs like Chartreuse or Benedictine with fruits, herbs, and spices along with a sweetener, used medicinally and as a beverage. Today, the words cordial and liqueur are often used interchangeably, and mingled with terms like aperitifs and digestifs enjoyed in small amounts to stimulate the appetite before a meal or aid digestion afterward.

Personally, I like them for the taste. A wild fruit cordial is a rare treat – less common than jam – and one that can’t be bought, at least at the same quality of what you can prepare at home. Both fruit liqueurs share a stunning magenta hue with a delicious flavor to match. I serve these cordials and liqueurs to company and at small cooking classes I teach as a treat anytime, but especially during the holidays. With the bumper crop, and the excess shared, it seemed like a good year to head back into the kitchen to make another batch and refine my recipe.

No special equipment or ingredients are required to make cordials – just berries, sugar, and alcohol. In other words, you should definitely try this at home. Last September, after collecting my own batch, and gratefully receiving surplus from others, I started on the beach plum liqueur by picking through and tossing out any stems, tiny branches, or damaged fruit. I measured out eight cups of the plums into a large bowl, mashed them gently with a muddler, and added sugar to draw out their liquid, a process similar to preparing strawberries for shortcake.

Next, I funneled the whole mix – seeds, skin, and all – into a half-gallon mason jar and added a bottle of my favorite local vodka from the Martha’s Vineyard Distilling Co. I repeated the process with a second batch the next week. With the lids screwed on tight, the jars sat in a food closet for a few months. Every week or so I turned the bottles upside down to redistribute the plums, which tend to fall to the bottom, and aid fermentation. Every few weeks, I sampled with a small glass to see how the concoctions were progressing. You want a rich, full flavor and a dense, rather than thin, consistency; the amount of time varies on the flavor of your fruit, the strength of your alcohol, and your own taste.

By Christmas season, the batches were more than ready. I strained out the fruit and pits and repackaged a good portion into glass bottles for gifts. I tied the necks with string, a sprig of pine, and a tag with the name and recipe. Recently, I had visited the Chicken Alley thrift store in Vineyard Haven and picked up a dozen or so cordial glasses for $1 or $2 each. I tied two tasting glasses around the neck of each bottle.

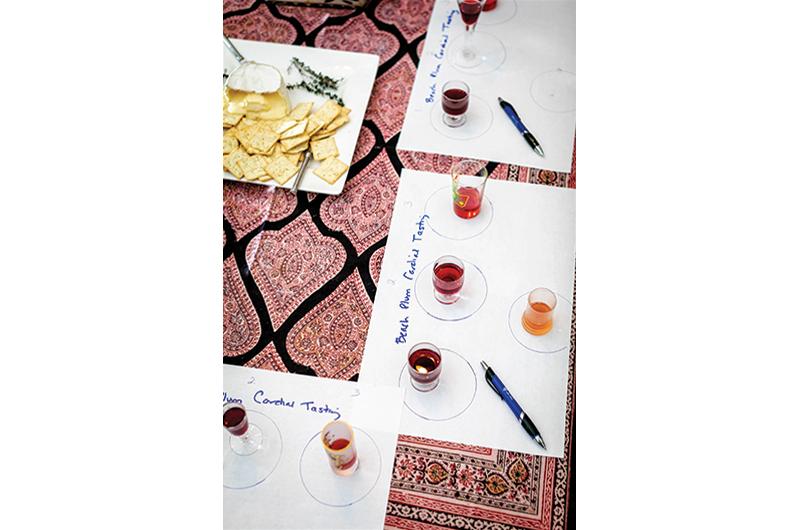

They were a hit, but I wanted more information. Was I doing all that I could do? Did others have a better recipe or method? In January, before a predicted snowstorm, I organized a blind tasting of beach plum liqueurs. I knew of three other Vineyarders who had also made home-made batches, so I invited them along with their partners. Curious about how results might differ, I laid out paper mats with numbered circles. I poured everyone’s beach plum liqueurs into beautiful small glasses of all shapes and sizes and placed them in the circles. We laughed when one was opened and nearly exploded all over the counter. This turned out to be beach plum kombucha made by one of the guests – altogether different, but fun to sample.

Right off the bat, we noticed differences in the clarity and consistency. Some were thicker, some thinner. This had everything to do with straining; interestingly, each had used a different method. The thinnest – a bit too thin – was strained using a coffee filter. The thickest – a bit too thick (mine) – was strained with a medium-fine strainer. A few people liked the thicker version. In a taste test, there’s a range of differing tastes and preferences. But we all agreed that the middle one, strained in three layers of cheesecloth, was clear and beautiful with a silky texture. I vowed to try this method the following year.

The flavors varied, too, depending on the amount of sweetener used and whether the plums were left whole or gently mashed. In our tasting, the two liqueurs with crushed fruit garnered the most admirers. Tasters described those as rich, dense, tart, complex, balanced, fruity, and not-too-sweet. One had kept the plums whole and didn’t break them down before adding the vodka; that one wasn’t as flavorful. That person had also used half the amount of fruit, which could have explained the difference.

To round out our tasting, we tried a commercially made beach plum liqueur. It lacked the delicious flavor of the beach plums altogether. All the liqueurs we tested contained vodka, which lets the essence of the fruit shine through. One person had made a version using Bombay gin, which we tried separately. We all agreed it was really good too.

While autumn olive cordials are unlikely to overtake beach plums in popularity, they make a good substitute in years when beach plums are scarce – and can even be made using the same recipe. Both beach plums and autumn olives are tart and astringent, and therefore require more sweetener than other fruits. When using raspberries, currants, blackberries, or other fruits containing more natural sugars, you may need to experiment with the amounts of fruit and sweetener required.

For the autumn olives, I made one batch with mezcal instead of vodka, and used a combination of sugar and local honey. Mezcal is a traditional Mexican spirit made from the agave plant (like tequila) but roasted to give it a smoky flavor. I branched out to a Concord grape liqueur, too, but I admit the complex and unique flavor of the beach plum is still my favorite.

Even after all this – or maybe because of it – when a friend from California sent me a box of lemons from her backyard tree, I turned it into limoncello using a recipe she shared with me from the internet. The few limoncellos I had tried over the years were very strong, and I figured by making my own I could tailor it to my own taste. It worked, though I’m still experimenting with that recipe to find my perfect method. All of which is to say, the next time someone gives you lemons, or beach plums or autumn olives, you know what to do.

The following recipe was originally published along with this article: