This summer, to commemorate its founding as the Dukes County Historical Society 100 years ago, the Martha’s Vineyard Museumis honoring the work and life of Stan Murphy, who died in 2003 but also would have turned 100 this year. Arguably the Island’s most celebrated painter, and not incidentally, its great portraitist, the exhibit, which opened in May and closes in mid-August, seems like not only an inspiration but also a gift to the public, for in his half-century of living on the Vineyard, Murphy painted images of this Island with deep affection and uncanny knowing.

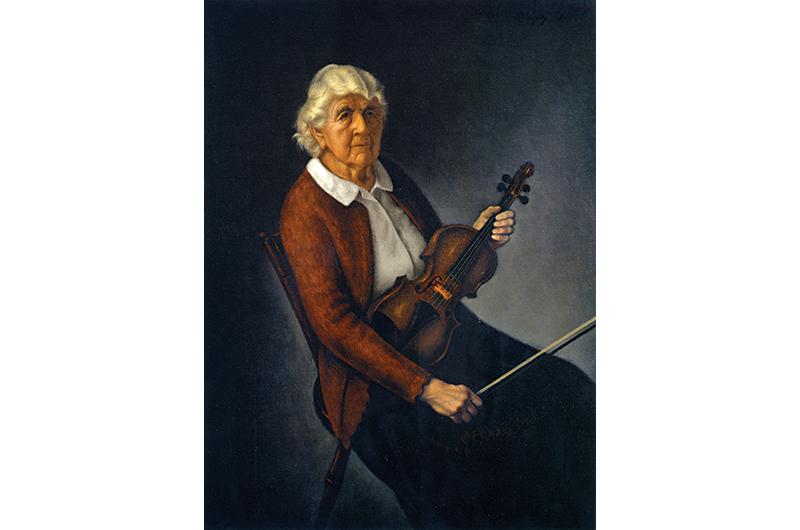

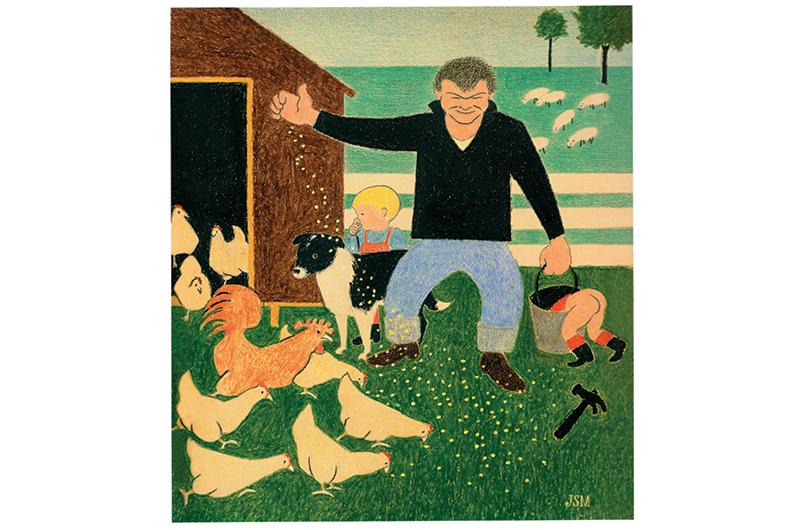

He painted farmers and their animals, fishermen and their boats, firemen and selectmen: Pooles, Flanders, Whitings, Alleys, Tiltons, Murphys, and all. He painted the working class when that meant everyone, and the natural and extremely rural life that they lived. Murphy caught the aura of matter-of-fact happiness in the air then, and he also caught the Island at a historic and transitional time before inevitably it began

to change.

Anna Barber, a tall and graceful woman who has a quiet passion for her work, is the curator of the centennial exhibition. The decision to mount the show came during the pandemic, when the museum closed only a year after its gala opening in its new home above Lagoon Pond in Vineyard Haven, and its focus had to turn to online programming and plans for the future. In the eyes of Barber and her team of assisting curators, the new Murphy exhibition is a BIG show, embracing “an individual and idiosyncratic man, his many talents, and his adaptation to the Vineyard.”

It is also Island-sized, intimate, and deeply connected to the land. “We have to remember our origins as a historical society,” Barber said, “which is a great responsibility. Our collections exist for the purpose of telling stories that may be long forgotten.”

Murphy, she said, is a perfect example of art and history intersecting. He served on the board of directors for the Historical Society for many years, and was even vice president for two terms. During his tenure, Murphy facilitated additions and the display of the decoy collection, and wrote the now rare book Martha’s Vineyard Decoys (D. R. Godine, 1978). The only decoy Murphy carved himself, a beautiful merganser with a softly curving neck, was a labor of love, with living detail that was both art and function.

“Murphy’s story,” she said, “is not just about his art, but about his life on the Vineyard too.”

Barber studied archeology at the University of Indianapolis before joining the museum sixteen years ago, and often notices that discipline’s similarity to curating. Last January, back in the days of wind and new snow, she sat at her desk inspecting a small sketchbook that had belonged to Murphy, which she was appraising for possible inclusion in the exhibition. This was one of her early steps into the long and demanding preparation for the show, and she was smiling at having discovered in the memo-sized notebook a colorful sketch of Thomas Hart Benton and his wife, Rita, at home, which spoke to the early and long friendship between the two men on the Island.

On another day, she had propped up for contemplation an image of Murphy’s 1948 portrait of George A. “Pat” Hough, the father of the Vineyard Gazette’s famous editor Henry Beetle Hough, who, among other historic deeds, had given his son the ownership of the newspaper as a wedding present. The painting was an early work in oil and quietly engaging, one of Murphy’s first creations after his arrival on the Vineyard. But it was also aging and its surface feathering, which raised the question of restoration, an expensive undertaking.

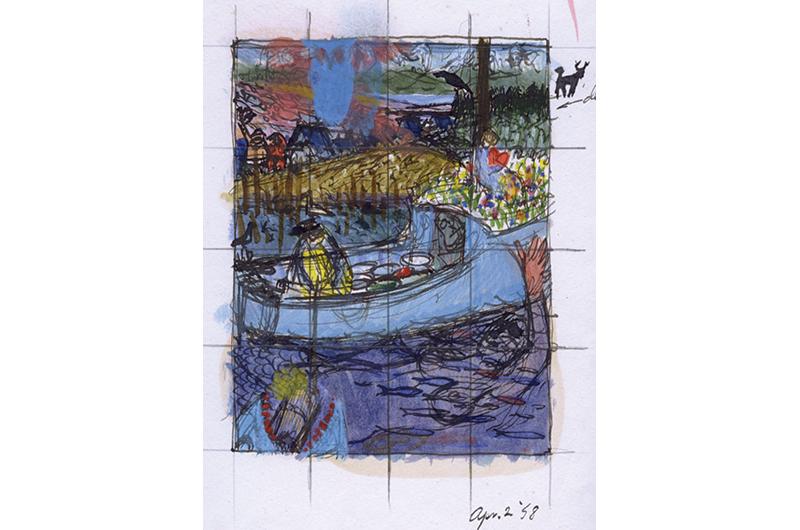

Most days Barber also kept at hand a fat folder containing images of Murphy’s major works, for reference or simply to feed her thinking. It was a modest sample of all that was in her head then. The Murphy collections at the museum are large, particularly since, fourteen years ago, many hundreds of his early pieces, including as many sketches, were donated by his family. These have been useful in dating Murphy’s work, for even in the early days he was scrupulous in adding thoughtful notations to himself on the face of the work as well as a signature on the back.

The notebooks also helped to document the beginnings of Murphy’s career after World War II, first in Okinawa and then at The Art Students League of New York, where he had enrolled in a course in commercial art, working mainly on lithography and cartooning, but also creating his first portrait in oil. Murphy and his wife, Polly Woollcott, lived in Hell’s Kitchen for a year before moving to Martha’s Vineyard in 1948, where Polly’s family had summered for years. From then on, the Island was the most significant element in Murphy’s life and art.

Murphy’s first years of Island life seemed to unfold like an old Vineyard tale: he was living in a chicken coop that was converted into a small home on Everett Whiting’s farm, earning his keep with barnyard chores, scalloping, and stocking shelves at Hancock Hardware. With the dawning realization that he wanted to be a painter, he was also going door-to-door seeking commissions to do portraits of Islanders and their homes. His early success with the Broadway actress Katharine Cornell, who engaged him to paint her house at Tashmoo called Chip-Chop and was eager to introduce him to friends, was providential and enabled him to begin a career. Eventually, it also resulted in a warm and close friendship with Cornell as well as a commission to create the large four-panel historical mural for the Katharine Cornell Theatre in Vineyard Haven, which still hangs on its walls. But it was not long before Murphy wanted to seek out his own subjects to paint, for the sheer pleasure of their company and the exposure to their Vineyard ways.

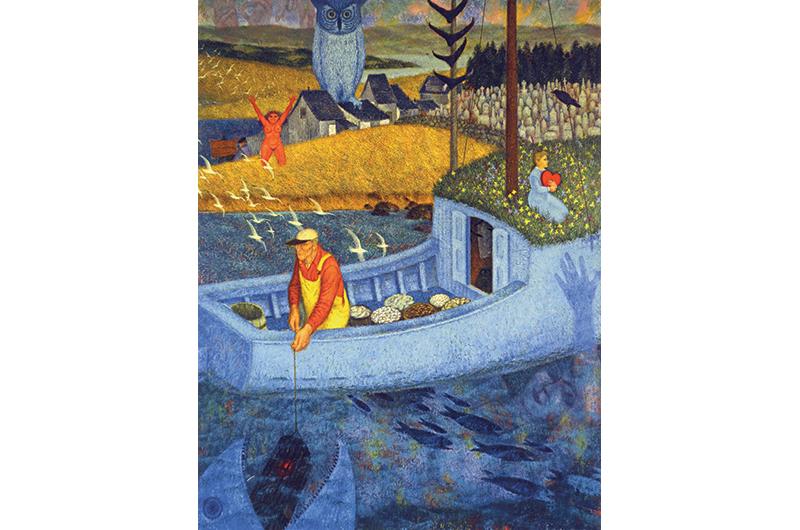

Kib Bramhall, an Island painter since the 1950s, was the subject of several portraits and a longtime friend of Murphy. A typical sitting, he said, often began with a detailed pencil sketch and could last two or three hours. To finish a painting, Murphy often invested several months. The very complicated painting of Ernest Mayhew and his boat, which told several stories at once and is entitled Biography of Ernest Mayhew, took more than a year.

“Murphy talked while he painted,” Bramhall said, “exploring, getting to know you. At the end he’d say simply, ‘You could buy it if you want.’” Bramhall grinned, adding that Murphy usually played opera music during the sitting and smoked a cigar.

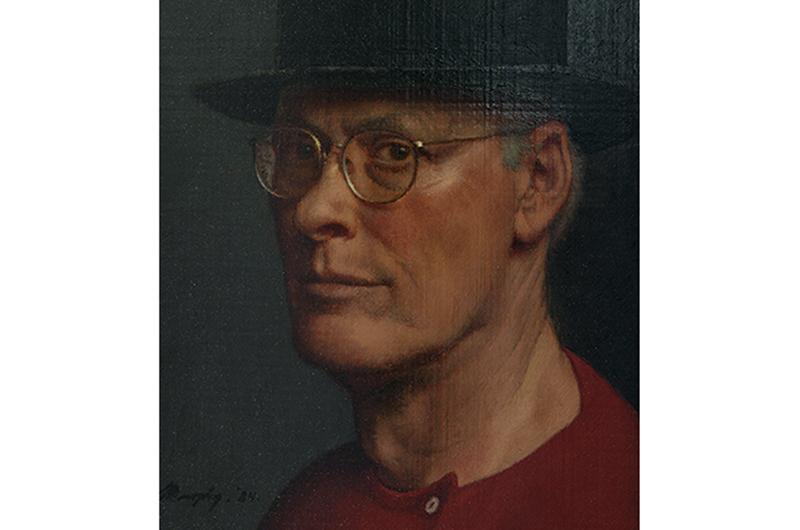

Kib’s wife, Tess Bramhall, an author and conservationist, also had multiple sittings with Murphy. She recalled his asking her if he might do her first portrait “as a Flemish painting,” a reference to his deep admiration for the Old Masters, which she took as a supreme compliment. Never a fan of the Abstract Expressionism that swept New York City in the 1940s and ’50s, Murphy often said that his art education came with the many hours he had spent alone at the Metropolitan Museum, immersed in Rembrandt and his famous self-portraits.

By the time that Murphy decided to rent a small studio space at the top of a neighboring barn, he was painting seriously and living a Vineyard life. He fished and clammed and hunted deer and geese; he built his own lobster pots, which Ernest Mayhew, Robert Flanders, and Dan Larsen taught him how to set; he acquired a boat and took his family for picnics out on the water. The Murphy family – Stan, Polly, Chris, Laura, Kitty, and David, plus the dog and the cat and a trio of geese that Murphy had fed and befriended and who followed him everywhere – were living in an old house on a working dairy farm in Chilmark, not far from the present-day site of Grey Barn.

In 1959 Murphy, who disliked the prospect of seeking an agent for his work in New York and generally eschewed the mores of the New York art world, opened a gallery to sell his paintings. Housed in a shack that he helped to build, surrounded by pastureland and not far from his house, it was one of only a few such enterprises on the Island. For the next four decades, the gallery opened almost every summer. There were festive events with each exhibition. But Murphy rarely attended his own shows; he had a very private and serious way about his own art and felt only anxiety and discomfort about these social events, which Polly happily managed.

Murphy had many moods and a full range of temperaments. He had a straightforward, serious, and quiet presence, but he also had a sense of humor and a big laugh. As his daughter Laura put it, he was “amused even with himself and the oddness of being alive.” One self-portrait, a simple sketch in colored pencils, pictures him in a balloon-shaped hat composed of many colors. He painted the Everett Whiting family on their farm like an affectionate cartoon, which Allen Whiting – at the time, the toddler in the picture upside-down in a bucket; now a revered landscape painter – identifies as “pop art before its time.”

Murphy also had a practical side, which may have been a factor in his habit of cutting up paintings that he didn’t like but keeping the parts that pleased him. Occasionally he would offer one of those fragments – of a hand, for example – to a friend.

Even in his more serious works, Murphy often let a note of whimsy or mystery creep in, like a reminder of the odd turns in life. In the almost fantastical painting called Laura and Kitty on the Path to Bannie’s, he pictured his daughters, then aged eight and ten, soon after their recovery from a near-death experience with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. The girls are walking across a hayfield, jumping and waving in play, a scene that Murphy has painted at an angle, turning the hayfield on its side and depicting the girls as tiny figures, emerging from the hay like happy runaways from a children’s book. For many decades, this innately personal painting hung over the mantlepiece at the Murphy’s house. It’s painted on a small, recycled door of old pressed wood, which resulted in irregularities in the paint surface, one of which he covered, almost unnoticeably, with a trio of small geese swimming in the water nearby.

Murphy had said early on that he could paint anywhere. But it was also true that in his mind and eye and hand, he was most deeply connected to his surroundings on the Island. “You learned to know that Stan’s entourage was in his painting,” Bramhall pointed out. “The flights of birds in the sky, the flowers and the other little things that he tucks into the corners or behind a rock are what was in his head.” In his determined and solemn way, Murphy was slowly studying the Island that he was painting; and what he saw on the face of a fisherman, or in a trio of selectmen on the steps of West Tisbury Town Hall, or in a rock covered with delicate lace-like lichen was what he felt was real and true.

The painter Rez Williams, who with his wife, the artist Lucy Mitchell, were close friends of Murphy’s, put the same thought slightly differently. “When Murphy chose his subject, there was something very selective and methodical going on, for it also involved his choice of a landscape and a setting. This speaks to the discreet and detailed nature of much of his portraiture,” Williams said. “In his painting of Alfred Vanderhoop, a Wampanoag tribal elder and a fisherman all his life who is shown working the local waters in his boat Red Wing, you are portraying his history, his work, and the landscape in which he grew up, now called Aquinnah. It is an important part of Murphy’s collective portrait of the Vineyard community.”

In February, Barber was beginning to put the master plan for the centennial show into effect. This meant mapping out the layout for the main room of the exhibition (and perhaps adding an additional wall to the space); bringing together the many paintings and portraits on loan from owners around the Island; reproducing multiple examples

of a small and early Murphy sketchbook for visitors to view; and composing and producing the show’s catalog. The final and most delicate step of designing and hanging the show would come about three months later and be her greatest and most essential challenge.

Barber thinks sensitively about stories: how they are told and flow and what not to leave out. She also thinks about the nature of a retrospective exhibition such as the one she was curating, which is intrinsically about Murphy’s growth as an artist and an Islander and involves finding the best examples of that to lead a viewer along his path. She is aware of the conundrum of having a big show in a small museum, but she is also energized by that reality and inspired by the show’s color and vision and message. It is an historic show, and that historic value can only grow, she knows, which would fulfill the museum’s mission.

This spring, at last Barber’s work was done and the art was hung. The catalogs were printed. The doors were unlocked. Opening night of the Stan Murphy retrospective was as grand an occasion as forecast, enriched by the attendance of three generations of the Murphy family and packed with fans and friends, several of whom could recall, with ironic smiles, the painter’s aversion to his own art openings.

In the three adjoining galleries and hallways of the exhibition, which will remain open through August 21, a selection of paintings, portraits, and drawings from more than fifty years of Murphy’s art is hung like a journey through his life on the Vineyard – a story of family and friendships and landscapes and a hard-working community of Islanders. Like a reminder of Murphy’s presence and his dedication to his work, a number of his many self-portraits appear at intervals – not only the classic gentleman in a red derby hat or the casual iconoclast at work in his crowded studio, but several of his whimsical “ancestor” series, in which he pictured himself as a caveman, a monk, or the seventeenth-century Rembrandt.

Beginning with his early days studying the work of the masters at the Frick Collection and the Met, Murphy had wanted to become a great painter. His life on the Vineyard had only confirmed his spirit and commitment. In all the ways that this elegant and loving retrospective displays, this show is a tribute to Murphy’s place on the Island and to his respect for its people and history.

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)