In late July of 2020, a middle-aged man became sick after going crabbing in Chilmark Pond. His mother, Carol Forgionazze, a nurse practitioner at Island Health Care in Edgartown, recalled him returning home late, complaining he wasn’t feeling well. He was stumbling, and “there was something off about his speech,” she said. She asked if he’d been drinking, and he assured her he had not. He had only been in the pond, where he’d snagged a few small crabs. His symptoms grew worse.

A few hours later, Forgione found him slumped over on the porch, disoriented, and complaining of painful swelling in his feet and hands. “I said, ‘What is wrong with you?’ And he says, ‘I don’t know, I don’t know.’” She suggested they go to the emergency room, but he refused, insisting he would be fine. His worst symptoms did, in fact, fade over the next few days, though he was unable to work for weeks and his muscles remained sore for six months. The cause remained, and technically remains, a mystery. But when Forgione saw a letter to the editor in the Martha’s Vineyard Times a few weeks after the incident that mentioned similar symptoms could be caused by exposure to toxins sometimes produced by blooms of water-loving microbes called cyanobacteria, she thought she had an answer. The letter was written in response to an article that described how especially bad blooms can cause a kind of paralysis. “I read that,” said Forgione, “and I said, ‘Oh my God, that’s what he has.’”

At the time, in 2020, the Island had no research capacity to sample Chilmark Pond soon enough after the incident to confirm whether a toxic bloom was underway. But the frightening incident, reported at the Chilmark select board meeting that September, was enough to inspire concern among Islanders and Island health officials.

“People were really scared,” said Emily Reddington, who directs the Great Pond Foundation, a Martha’s Vineyard nonprofit devoted to stewardship of Edgartown Great Pond. Citizens wanted to know if they could breathe the air around the pond, or if they could bring their pets near the water, or what causes blooms, she said. “And we said, ‘We don’t know.’”

This was not the first cyanobacteria-related incident on the Vineyard or on nearby Cape Cod. Since 2017, the Association to Preserve Cape Cod has monitored dozens of ponds on the Cape for harmful cyanobacteria blooms, resulting in several health advisories each year. In 2019, a dog died on the Vineyard after suspected exposure to a toxic bloom in Chilmark Pond. But the case involving Forgione’s son was believed to be the first on the Island where a human was sickened. It also highlighted the need for a better way to test for toxic cyanobacteria blooms.

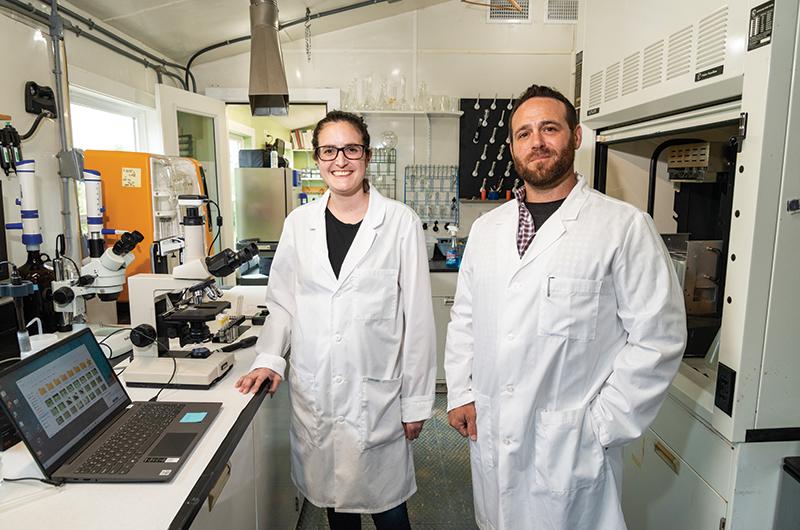

“We got together to make sure that never happened again,” said Julie Pringle, the scientific program director for MV CYANO, a new effort to monitor the Island for toxic cyanobacteria blooms. Now in its second year of operations, MV CYANO, which is funded by the Chilmark Pond Foundation, the Edgartown-based Great Pond Foundation, and various other Island institutions, is one of two cyanobacteria-monitoring efforts on the Island using new tools to identify when there’s a risk for toxic blooms in order to alert health officials. The second project, called CyanoCasting, is a collaboration between the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (MVC), the Wampanoag Environmental Lab, the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group, and researchers from the University of New Hampshire Center for Freshwater Biology and Ecotoxicology.

This summer, both programs expanded to monitor more Island ponds after a pilot summer in 2021. “What we’ve developed on Martha’s Vineyard is ahead of what other communities are doing, even on a state level,” said Reddington. In addition to monitoring for toxic blooms, scientists are using the monitoring data to better understand the unique dynamics of cyanobacteria blooms in the Island ponds’ brackish waters.

Sometimes called blue-green algae, there are thousands of species of cyanobacteria, which are some of the oldest and most diverse organisms on Earth and are found in nearly every body of water on the planet. Super-efficient at photosynthesis, cyanobacteria were crucial to the creation of the current oxygen-rich atmosphere some two billion years ago, and they remain a key player in maintaining it. Most of the time, therefore, cyanobacteria are harmless and necessary.

But changes to their habitat can cause some populations to grow rapidly, or “bloom.” During a bloom, some species of cyanobacteria produce compounds at concentrations toxic to humans and other animals. Depending on the type of toxin and the length of exposure, symptoms for people can include nausea, diarrhea, blistering around the mouth, and neurological symptoms, such as numbness. The most common symptoms for animals include vomiting or foaming at the mouth. Exposure most often is a result of ingesting contaminated water, but can also happen through cuts in skin, through contact with eyes, or by breathing in aerosolized toxins. Blooms can also reduce the amount of oxygen available to other marine life, causing die-offs, and other damage to ecosystems.

Not all blooms are harmful, but toxic blooms pose a growing threat to people and ecosystems around the world. Globally, the increase is driven by two factors, both of them caused by human activity. The first is nutrient loading from agricultural runoff and pollution, which provide the bacteria with excessive food for feasting. Equally important are the warmer waters that result from human-caused climate change; heat increases the rate of growth of the bacteria. Some research has also found that the combination of warmer water and nutrient overload, known as eutrophication, often favors those cyanobacterial species that produce toxins. Increased atmospheric carbon, rising sea levels, and changes in salinity can also affect the likelihood of harmful cyanobacteria blooms.

There is not yet sufficient long-term data to determine definitively whether toxic blooms have increased in frequency on the Vineyard, and if they have, why. But the local factors favoring such blooms are well-documented. “I think it is becoming more of an emerging concern because of the increase in temperature and the increase in nutrients in our ponds,” said Pringle.

According to Sheri Caseau, the water resource planner at the MVC, the main culprits on the Island are likely nitrogen from septic tanks and phosphorous runoff from fertilizer used on lawns and gardens. The increase in impermeable surfaces, such as roads and parking lots, also increases the amount of runoff carrying nutrients into watersheds. Warmer water seems to be less of a factor at the moment, Caseau said, but will likely increase the risk of future blooms. “We just don’t know what climate change will bring,” she said. “It’s changing habitats; it’s changing ecology. That upsets our balance.”

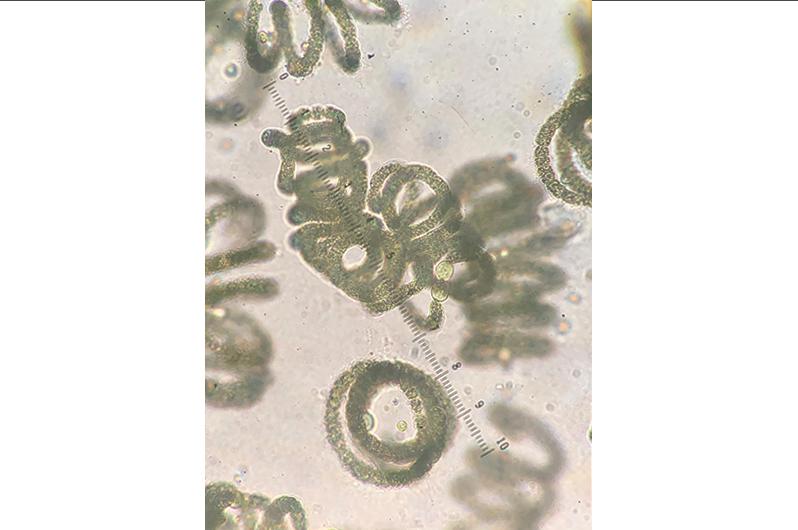

Part of the challenge to scientists and would-be crabbers alike is that it’s not always easy to distinguish a harmful bloom from a harmless one. Often, cyanobacteria blooms leave telltale green or bluish clouds shimmering on the surface of water, but just as often they don’t, said Reddington. Some cyanobacteria can grow in mats on the bottom of ponds. Other cyanobacteria – called picocyanobacterial – are so tiny they can be invisible even at high concentrations.

What’s more, just because bacteria are in bloom doesn’t mean they’re producing toxins. “That’s sort of the scary thing,” said Reddington. “There’s a whole bunch of variability. You can have green water that’s not toxic, and you can have clear water that is.” Being able to unambiguously identify when blooms are happening and whether they are likely to be toxic is the purpose of the monitoring projects. Results from the first year are in.

Last summer, MV CYANO measured cyanobacteria concentrations in Chilmark Pond, Tisbury Great Pond, Crackatuxet Pond, and Edgartown Great Pond. No dangerous blooms occurred in any of the ponds, Pringle reported at a Zoom meeting in March, though there was a spike in cyanobacteria concentration in Crackatuxet Pond in August. However, no toxins were detected in samples taken from the pond.

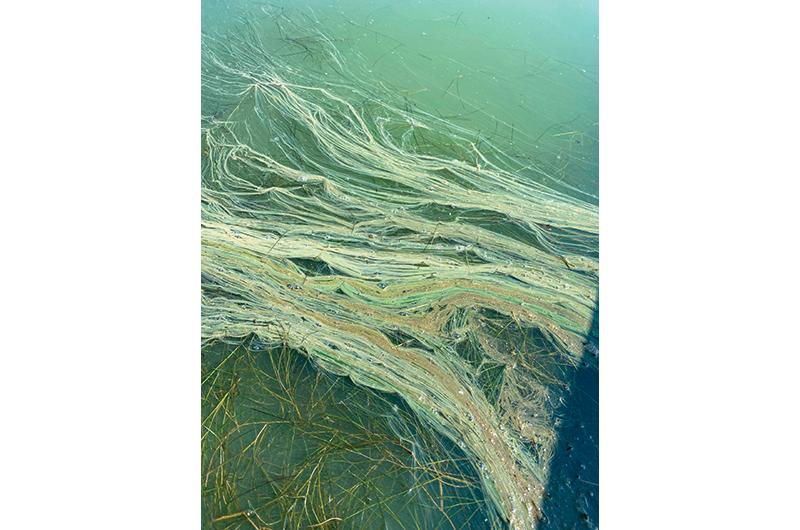

The most serious bloom last summer occurred in Squibnocket Pond, which the Wampanoag Environmental Lab in Aquinnah routinely monitors. In July, the pond developed a green cloudiness and floating algal mats that “you would not care to step in,” said Andrew Jacobs, who manages the lab. Using a device called a fluorometer to distinguish cyanobacteria from other phytoplankton, such as algae, both the lab (which also analyzes samples via microscopy) and MV CYANO confirmed it was indeed a cyanobacteria bloom. Water samples sent off-Island by MV CYANO for analysis also found that a toxin called microcystin, which can cause liver damage, was present. The concentration of microcystin was just below EPA guidelines for limiting access to recreational water, but health officials closed parts of the pond and posted warnings.

“Once cyanotoxins are detectable, that’s within the realm where there should be concern for toxicity to humans and non-human animals,” said Reddington. “The field of knowledge about cyanotoxins and their impact is emerging. And whenever there’s a branch of science that’s still developing, and there’s human risk, those are places where an abundance of caution is really important.”

That said, Reddington also points out how caution must be balanced with the many ways people use water on the Island. “We have an Island covered in water and surrounded by water. People are here because they want to be in it. If they just are told stay out of the water because there’s a risk, it’s not a really good answer…I think we have to be a step ahead. Otherwise, people couldn’t feel safe using the water the way they wanted to.”

Squibnocket Pond abuts Wampanoag land, and the lab has monitored water quality there since 2004. The monitoring program initially focused only on monitoring chlorophyll – which can indicate the concentration of all types of phytoplankton – but the lab expanded to monitoring for cyanobacteria specifically in 2021 “when we realized that there was a little bit more of a problem with cyanobacteria blooms across Cape Cod and the Islands, and how they were a symptom of something larger, not just a random presence,” Jacobs said.

In order to learn more, the Wampanoag lab started collaborating with Nancy Leland, a microbiologist at the University of New Hampshire, who is part of the consulting team working with the lab, the MVC, and the shellfish group’s monitoring efforts. Their first project together focused on the relationship between alewife (herring) in Squibnocket Pond and populations of cyanobacteria. Alewife eat zooplankton, which in turn eat cyanobacteria, linking the two across the food chain and providing a potential route by which toxins might accumulate in fish. The relationship can work in the other direction as well: fish can impact zooplankton, which can impact cyanobacteria. “People typically think [cyanobacteria blooms are] all about the nutrients,” said Leland. “And I’m like, well, maybe sometimes, but not always. Sometimes it’s the fish!”

For Leland, the expanding monitoring efforts on the Vineyard have presented other opportunities for studying the ecology of cyanobacteria as well, with important implications for the ability to predict when blooms are likely to be toxic. The challenge lies in determining which types of cyanobacteria are present in a bloom. Different types of cyanobacteria have different pigments that enable them to photosynthesize light at certain depths and salinities. Using a fluorometer, those pigments can serve as a fingerprint to identify the types of cyanobacteria in a given sample.

“Once you know what’s there, you can pretty much put yourself into a general category of what kind of toxin you may be encountering, given the different genus,” said Leland. If a toxic type is present, water samples can then be taken and sent to a well-equipped lab to test for toxins directly, potentially triggering a health warning or other government response if concentrations are too high. Measuring toxins for every sample would be too expensive and time-consuming, said Leland.

Identifying toxic types is made even more difficult on the Vineyard because the pigment fingerprints Leland uses are based on data from freshwater ecosystems. Less is understood about cyanobacteria in the brackish water found in many Island ponds, including Squibnocket Pond. And what worked in freshwater ponds might not work in the variable waters of the Island’s Great Pond ecosystems. “What are those pigment fingerprints that we see in these brackish systems? And how are we interpreting those fingerprints? What are they telling us about the interactions between different types of cyanobacteria and how that might affect toxin production?” are all questions Leland and her colleagues are exploring. “It’s a very interesting and intriguing puzzle.”

A related question, though beyond the scope of the research happening on the Island, is why cyanobacteria produce the toxins at all. This is something of a hot topic among scientists who study cyanobacteria evolution and ecology, said Dr. Christopher Gobler, a biologist at Stony Brook University in New York who is consulting on the MV CYANO project. Only a handful of the hundreds of compounds cyanobacteria produce are toxic to humans and animals, but the evolutionary story of even the best-studied toxins has defied easy explanation.

For instance, scientists long believed some cyanobacteria produce toxic microcystins to ward off predators, such as zooplankton. But subsequent research found microcystins have no effect on predation; genetic analysis also showed that the bacteria’s ability to produce microcystins evolved prior to the appearance of zooplankton on the scene. Alternative explanations are that cyanobacteria use the toxins to compete with other species of cyanobacteria, or that the microcystins enable the bacteria to collect nutrients from the environment. Their true function, however, and the function of many other compounds made by cyanobacteria, is unknown, said Gobler.

Whatever cyanobacteria use their toxins for, though, we can be sure it doesn’t have anything to do with us. “They don’t do it to make us stop swimming,” said Leland. It’s a reminder not to blame cyanobacteria, which have lived on Earth for more than three billion years, and remain responsible for much of the oxygen in the atmosphere, for a problem we primates have brought on ourselves. “Nature will give us beautiful things if we respect her, or can turn against us if we don’t,” said Forgione, who, two years after her son’s episode, is pleased to see the attention being paid to cyanobacteria blooms. “If this hadn’t happened, we wouldn’t know anything about this today,” she said. “Someone else could get hurt.”