Fifty years ago, Martha’s Vineyard existed as if it were a piece of precious metal on a jeweler’s workbench. The looming question was who would fashion the tools that would shape the future of the largely rural, seasonal vacation Island: developers, the federal government, the state of Massachusetts, or Islanders themselves.

Martha’s Vineyard then was a relatively quiet, backwater vacation destination. The music, film, and media celebrities among the Island’s seasonal residents generally wore their fame lightly and shunned the tabloid glare. Presidential visits were still rare. It had been ninety-eight years since Ulysses S. Grant was the guest of honor at a dinner held at the Sea View Hotel in Oak Bluffs. It would be twenty-one years before president Bill Clinton and his family would arrive on vacation, followed later by the Obamas, by which time the term “Hollywood East” had been added to the Island lexicon.

The 1970 census pegged the official year-round population of Dukes County, which includes the Elizabeth Islands, at 6,117 people. But it was beginning to grow at a rapid pace. A wave of young people rooted in the sixties counterculture was just beginning to wash ashore. By 1980 the year-round head count was 8,942; by 2020, it was 20,600.

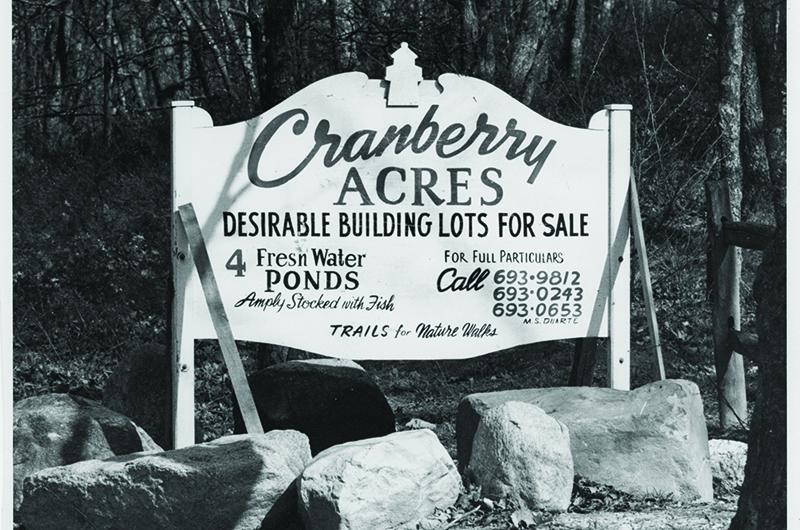

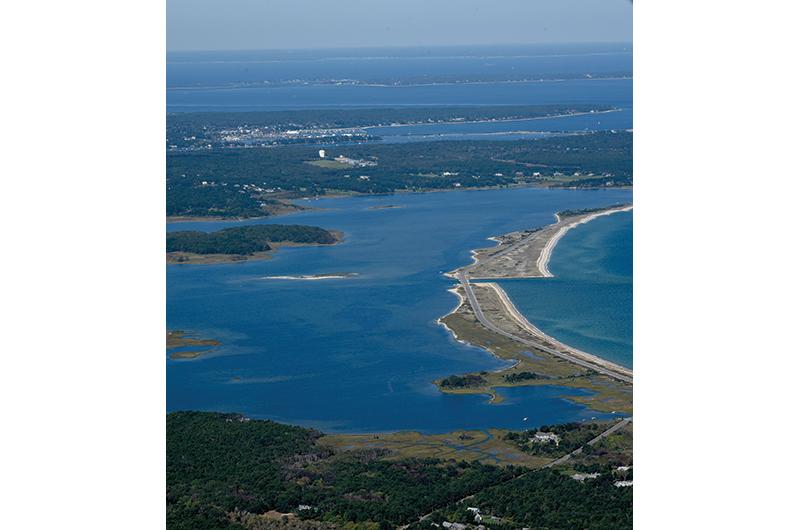

Developers, unfettered by zoning and subdivision rules, looked to transform large tracts of land into suburban-style housing. In particular, looming in the wings was the Strock family’s Island Properties proposal to create a golf course and 867 half-acre housing lots overlooking Sengekontacket Pond in Oak Bluffs.

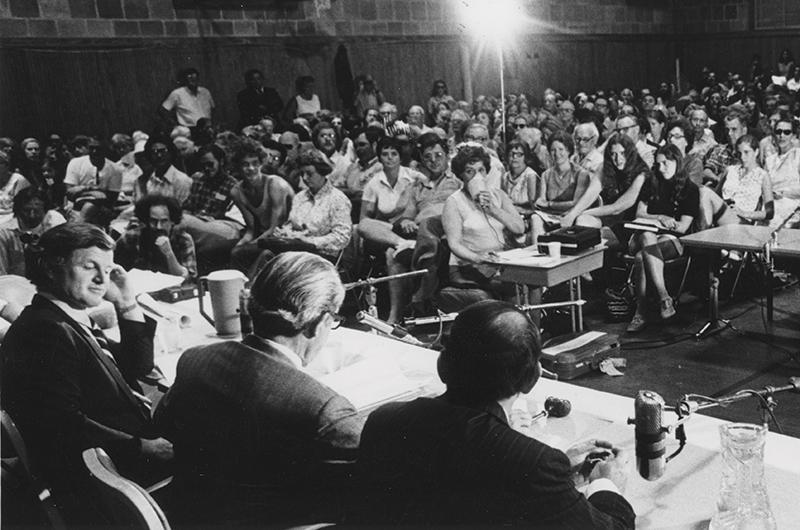

In Washington in 1972, Senator Edward M. Kennedy introduced his Nantucket Sound Islands Trust bill to place Martha’s Vineyard, the Elizabeth Islands, and Nantucket in a protective federal land trust that would restrict development and give federal authorities oversight over local decision-making. The proposal, which came with little or no advance warning and would have created something similar to the Cape Cod National Seashore, sharply divided year-round and seasonal residents.

Many of them called on their state government to take preemptive action, and on July 27, 1974, Governor Francis Sargent signed Chapter 637 of the Acts of 1974: An Act Protecting Land and Water on Martha’s Vineyard. The legislation created the twenty-one-member Martha’s Vineyard Commission, an unprecedented regional planning and permitting authority with a broad mandate whose powers had yet to be fully defined, let alone tested by the courts.

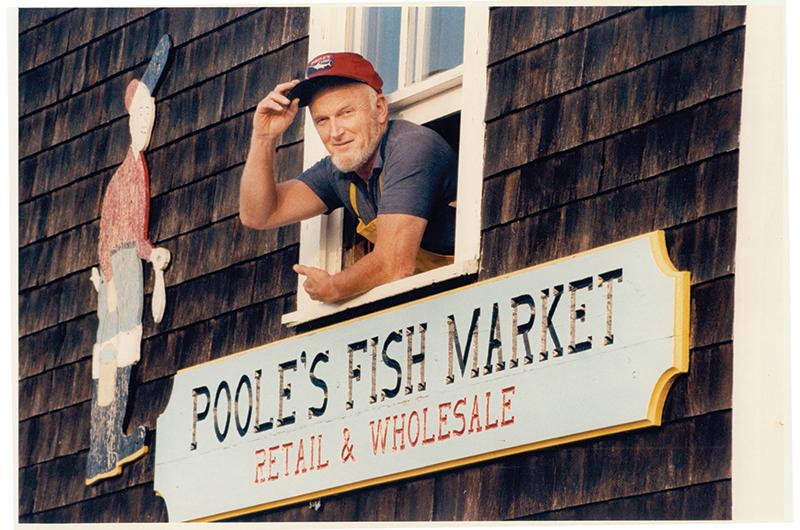

Nearly a half century later, only three original commissioners are alive and still living full-time on the Island: Douglas Cabral of Vineyard Haven and Gregory Coogan and Steve Amaral of Oak Bluffs. Looking back in conversations earlier this year, they, along with original member Everett Poole of Chilmark (who died in February), described the urgency to protect the Island and how they puzzled over the path to take.

“We were just overwhelmed with building and people moving in,” said Poole, a longtime Chilmark town moderator and retired fish dealer. “People were coming here because they could get a good job in the summertime and then sit on their asses all winter and complain they had no place to work.”

Cabral was twenty-eight years old and the managing editor of the Vineyard Gazette, then owned by The New York Times op-ed columnist James “Scotty” Reston and his wife, Sally, when he was elected to the commission. Islanders realized that the Vineyard was becoming a desirable place for second homes, he recalled, and there were no zoning controls in place to control development. At the same time, the quiet creation of the Islands trust bill by Kennedy and his friends in Washington and on the Island was “alarming in a different way.”

“The other dimension to that story was that Francis Sargent, the Republican governor of Massachusetts, was damned if he was going to have Ted Kennedy, the Democratic senator, create a land preservation mechanism on his Republican watch,” Cabral, now seventy-six and the retired co-owner and editor of The Martha’s Vineyard Times, said in a recent conversation. “And so, the state came along with a plan of its own that was invited by Vineyarders and somewhat more welcome than the Kennedy plan that would transform their home into a national historic park, which most Vineyarders, who had never been consulted in the development of Senator Kennedy’s legislation, didn’t like.”

Amid the social, economic, and political currents washing over the Island’s six separate towns, each jealously protective of its authority and skittish at any mention of the word “regional,” the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (MVC) emerged. The Kennedy bill, meanwhile, limped along for a few more years, eventually passing in the United States Senate before dying in the House of Representatives.

Located today in the Stone Building in Oak Bluffs, the MVC is still comprised of twenty-one members. Nine are chosen in Island-wide elections held every two years, with at least one and not more than two people elected from each of the six Island towns. Six are appointed by the towns’ select boards. One is appointed by the Dukes County Commission, and five are appointed by the governor, of whom only one may vote.

In recent years, the biennial election has generated few contests, and appointments have become mostly a rote exercise in reappointment. The majority of commissioners have served multiple terms and are north of middle-age. Four have sat on the commission for eighteen years or more.

But in November 1974, Islanders were keenly aware of the election stakes: voters faced a slate of forty-three candidates for the nine elected seats on the new commission. One week before the election, Vineyard Gazette columnist William A. Caldwell, a retired Pulitzer Prize–winning newspaperman and Island summer resident, emphasized the ground-breaking nature of the new regional permitting body: “The voter confronting that bewildering ballot Tuesday should be conscious of a heavy responsibility, not only to his town but to his Island, not only to his Island but to his state and indeed his nation. We are engaged in exploring a wholly new method of problem solving.”

Helen V. Manning of Gay Head (now Aquinnah), a Wampanoag and respected Island teacher, was the top vote-getter, with 2,161 votes, among the “first regionally constituted representatives on an agency unprecedented in the state, perhaps the nation,” the Gazette reported.

She was joined by elected and appointed members whose family names – Hancock, Flanders, Poole, Alley, Amaral – reflected deep generational roots. “The majority of the people were just ordinary folk,” Cabral said.

In the early seventies, Coogan had moved from Boston to the Vineyard, where his grandparents had a cottage. He was just twenty-five years old and working as a carpenter for Island builders Frank Fenner and Edward Medeiros when he was encouraged to run for a seat on the MVC to help bring another perspective to the table.

“I was a young kid with a lot of varied interests just trying to make a living,” the seventy-three-year-old retired Tisbury School mathematics teacher and former Oak Bluffs selectman said. “The towns were very afraid of losing power and so they wanted a mix of people on the commission – Ed Tyra [of Edgartown] was a builder. They wanted to represent the different interests to keep the economy vibrant because it was pretty slow back then.”

Amaral was a thirty-eight-year-old plumber working for his uncles when the Oak Bluffs selectmen appointed him to the MVC. He’d grown up fishing and hunting with members of his extended family and knew many of the commissioners. “Jean Hancock, Fran Flanders, and Edo [Potter]…it was a small community. We all clicked, and I enjoyed their company and they enjoyed mine,” he said.

Reflecting on when he could hunt miles of Oak Bluffs woodland without coming across a house, the eighty-six-year-old Amaral said he loved the outdoors but knew the Island was changing and needed to be protected. “I figured maybe I could help, or at least I could vote on something that I thought was right, anyhow. That’s what I did. After the two years, I’d had enough.”

Other commissioners were relative Island newcomers and arrived with professional backgrounds and an interest in conservation. George Mathiesen, the MVC’s first chairman, was a retired broadcast executive who moved to the Vineyard with his wife in 1971 and built Chicama Vineyards. Anne Hale, a Harvard-trained landscape architect, owned the Martha’s Vineyard Shipyard with her husband, Tom.

Coogan, in part, blames the lack of turnover at the commission these days on an early summer nomination deadline “when people are distracted and not thinking about the MVC.” He added that the commissioners behave differently now that meetings are recorded and available to stream at mvtv.org. “Cameras have changed the dynamic of meetings. Now everybody has to have their moment.

“Now you change a couple of commissioners every year,” he said, “but it was all new in 1974. There was a lot of feeling each other out, trying to figure out who we were as a group. And there were a lot of different personalities. Strong personalities.”

The act that established the commission imposed, with limited exceptions, a temporary moratorium of up to twelve months on the issuance of development permits. But there was no roadmap in the enabling legislation for how exactly the MVC was to go about protecting the land and waters of the Island. At the start of 1975, therefore, it was left to the newly elected and appointed commissioners to negotiate the regulatory territory between economic growth and conservation that would remain a consistent theme of commission action.

“The pressure was to create something from nothing,” Coogan recalled. “We didn’t have a roadmap. We didn’t have anyone to call and say, ‘What would you do here, what would you do there?’”

Poole underscored the unbroken ground the original members were crossing. “As I remember, there was just a very broad outline, and it was pretty much, ‘Here you go, boys, set it up.’ It was very difficult – it took a lot of time to determine exactly what the commission was going to do. I was busy then too.” He added, “God, those rides to Oak Bluffs were terrible after a day’s work.”

Commissioners got to work writing out goals and policies. But the inclusion of the words “rural quality” in the document language proved to be a hurdle. In a story published March 21, 1975, “Land Commission Finds Much Ado Over One Word,” the Vineyard Gazette reported that Poole was unhappy with the initial wording because he “feared those who suspect the commission’s membership is more concerned with the preservation of open-spaces up-Island than with the well-being of the down-Island towns would be confirmed in their suspicions after reading the preamble.”

Poole said, “It sounds like it was written in Washington.”

After some back and forth, acceptable wording was found. The policy was printed in full on June 13, 1975, on the editorial page of the Vineyard Gazette. It began: “It is the intention of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission that its efforts be directed toward the preservation and enhancement of the rural quality of life on Martha’s Vineyard and the unique character of each town. In choosing the word rural to describe the quality of life here, the commission intends to make clear its rejection of all that gathers under the adjectives suburban and urban.”

Cabral, who helped write the guidelines, said, “I think what everyone was trying to do, and this would’ve been true whether the Islands trust bill had prevailed or within the terms of the state bill, everyone wanted to keep things the same. They set out to prevent what has happened. That’s basically it. So rural character was a way to express that. They didn’t want it to become what it has become, and then pretty soon they saw that you couldn’t stop that from happening, but maybe you could make it as orderly as made sense to you.”

To accomplish their goals, the commissioners had at their disposal the designation of a District of Critical Planning Concern, which, when enacted, imposes regulatory oversight that supersedes town authority and boundaries. A project likewise could be designated a Development of Regional Impact (DRI) subject to MVC review and permitting based on a specific regional impact – for example, due to its size or by request of a town board. These designations proved to be the strongest tools in their toolbox.

In December 1975, the MVC approved a coastal perimeter district and an Island road district under which towns were required to follow the MVC’s guidelines and adopt new rules for the protection of the designated shorelines and roadways. For example, no stone wall could be moved or altered in the road district without a special permit. The coastal district guidelines restricted the height of structures and prohibited “dredging, filling, or alteration of any wetland or beach,” except for a use or structure allowed by special permit.

“The road district was key at that point because we were losing the personality of the Vineyard then,” Coogan said. Development was changing the quiet, rural quality of the roads and vistas many had taken for granted. Noting it was one of

the MVC’s first and lasting accomplishments, he said that with the possible exception of the Edgartown–Vineyard Haven Road, “You never drive a road on Martha’s Vineyard and think, ‘I don’t want to take that ride again.’ You never get tired of driving from Oak Bluffs to Edgartown along State Beach. You never get tired of driving up Middle Road. You never get tired of driving South Road.”

The first major court test of the MVC’s regulatory power came after the initial building moratorium halted the Strock family’s plan to put more than 850 houses on small lots along Sengekontacket Pond. The designation in 1976 of the Oak Bluffs Sengekontacket Pond District of Critical Planning Concern severely restricted the size of the proposed development.

In March 1977, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts affirmed that although the Oak Bluffs planning board issued Strock a permit in June 1974, the MVC’s authority must take precedence over town regulations when the commission’s regulations are stricter. The decision set the pattern for future challenges to the MVC’s regional land-use regulatory powers.

The most recent legal challenge, which was scheduled to begin in June in Dukes County Superior Court, is an attempt by Utah-based developers Douglas K. Anderson and Richard G. Matthews to overturn the MVC’s 10–4 decision in 2020 to deny their proposed “Meeting House Place” subdivision of roughly fifty-four acres in Edgartown.

During the two-year review process, their plan to build thirty-six market-rate homes was revised in an effort to address the concerns of the MVC and others. The final plan had twenty-eight market-rate homes, added fourteen below-market-rate townhomes, and included conservation acreage and a $1.1 million contribution to the Edgartown affordable housing committee. But in the end, the MVC ruled the project “did not provide sufficient benefits to outweigh the overwhelming detriment to the rural, natural character of the area, and the Vineyard as a whole.” Both sides can be expected to appeal any decision against them in the case.

When considering a project as a DRI, as the MVC did with Meeting House Place subdivision, it can exercise several options. It can decide that a project does not have regional impact and kick it back to the town; it can review the project as a DRI and stop it outright, as it did with Meeting House Place; it can approve it outright; or it can approve a project with conditions that may include financial mitigation or changes to the project scope. Once the MVC takes action, the local permitting and review process resumes.

In 1977, eighteen threshold triggers were listed under which a development would move from local town review to mandatory review. Over the years, the commission has continued to expand its DRI standards and criteria. The fourteenth iteration is a nineteen-page document that lists and describes seventy items under which a project is referred. A new addition in 2021 includes any demolition or relocation of a structure that is more than 100 years old.

A commercial establishment over a certain size also triggers an automatic DRI referral to the MVC. In March 2014, following a five-month process, hundreds of letters for and against, and a petition with almost 1,000 signatures, the MVC approved The Barn Bowl & Bistro bowling alley and restaurant on Uncas Avenue in the middle of Oak Bluffs. MVC approval came with thirty-five conditions, including nine related to ambient noise.

Asked about the difference between the MVC then and now, Poole said, “It’s much more involved in things that we didn’t pay much attention to start with.”

In their deliberation process, the commissioners may weigh a project’s “probable benefits and detriments,” even if “they are indirect, intangible, or not readily quantifiable.” The subjective nature of the evaluation allows the commissioners great latitude.

“I think it’s become more and more complicated and more and more of an intervener because that’s what happens to regulatory organizations. It’s how they work,” said Cabral. “And I think they’re also activated to some degree by a sense that the horses are out of the barn and they’re just trying to keep them in the field.”

The MVC’s annual operating budget is built chiefly on an assessment divided among the member towns on the basis of equalized property valuation. In January 1975, after some disagreement over staff – six versus five full-time positions – and town valuations, the commissioners approved a $104,350 budget that raised the eyebrows of frugal Island town officials. At that time, Tisbury paid the highest assessment: $25,179; followed by Edgartown: $23,957; Oak Bluffs: $15,263; West Tisbury: $5,798; Chilmark: $5,798; Gay Head: $1,527; and Gosnold: $378.

Today, the MVC has twelve full-time positions and a $2,032,789 budget. The ranking of assessments has also shuffled, reflecting the different rates of development and relative property values in the various towns. Edgartown’s assessment, now the largest, stands at $562,098; followed by Oak Bluffs: $201,499; Chilmark: $202,964; Tisbury: $178,954; West Tisbury: $166,626; Aquinnah: $44,993; and Gosnold: $8,255.

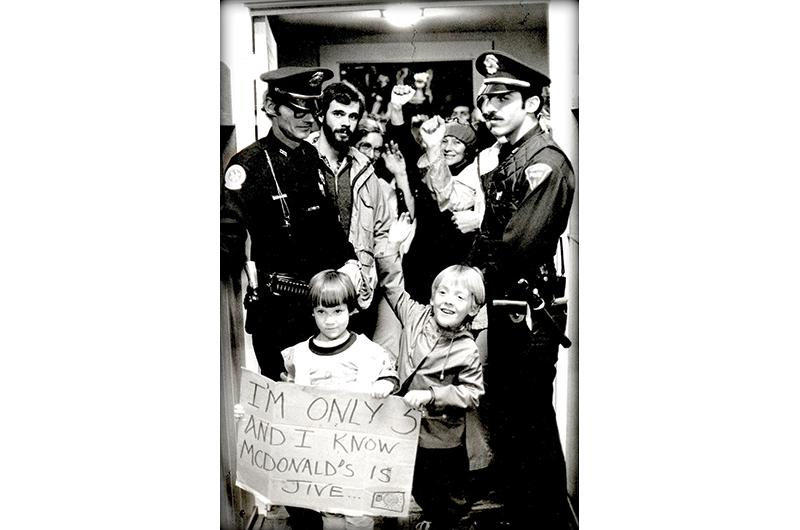

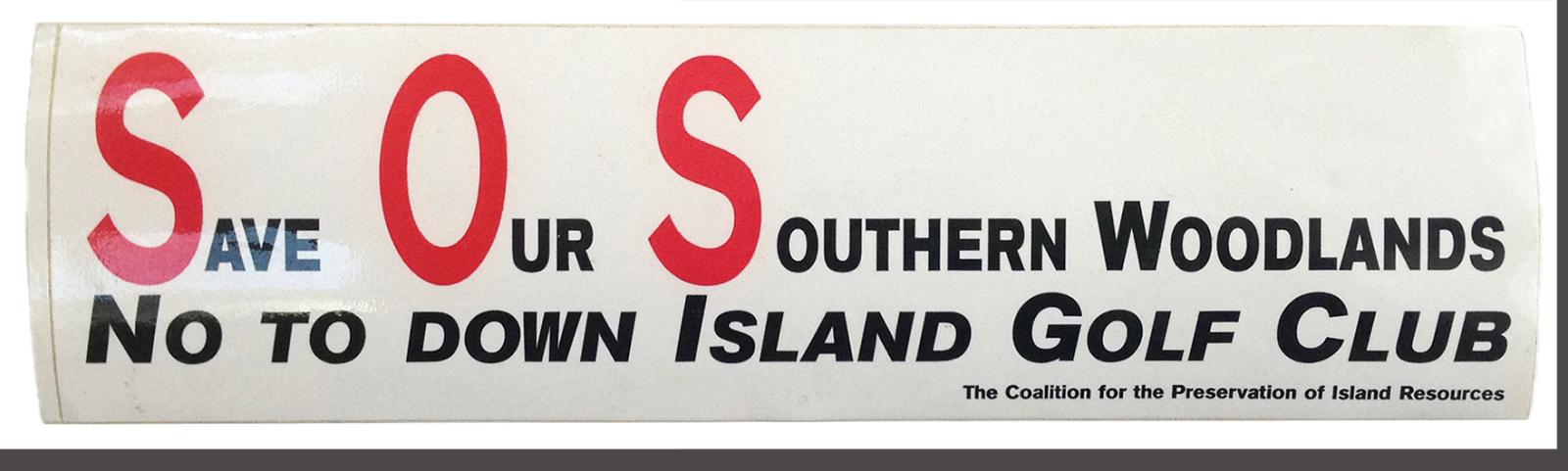

Over the years, towns have challenged the authority of the MVC. At one time, Tisbury and Edgartown withdrew from the MVC then later rejoined. In May 2003, Oak Bluffs voters considered withdrawing following a lengthy battle over the proposed Down Island Golf Club.

That proposal, which had strong support in Oak Bluffs, called for an eighteen-hole golf course and benefit package that included public walking trails, payments in lieu of taxes, an offer to lease a portion of the former Webb’s Camping Area to the town at no cost for camping, and a permanent conservation restriction over the entire property, now known as the Southern Woodlands between Barnes and County Roads. After a lengthy set of contentious hearings, MVC’s rejection of the plan spurred a call to withdraw, but voters decided to remain in the MVC.

Coogan said his motivation for his long service on the Oak Bluffs board of selectmen was to keep Oak Bluffs in the MVC: “I listen to friends, some who hate the commission and some who see the value in it – it’s always had a difficult role.”

Looking back, Coogan said, “It’s hard to compare today’s Martha’s Vineyard Commission with its first iteration. We were looking at major subdivisions back then. There was no nuance.”

Reminiscing about what the Island was like in the seventies, Coogan said he was living in a cabin off Old County Road in West Tisbury. “The Island was endless then to a twenty-five-year-old kid.” Coogan said he sometimes questions just how much the MVC was able to protect. “When I think about it, what exactly did we do? So much has changed and we were unable to stop all of that. So now the commission looks at things with a different lens because so much of the Island has been built out.”

He added, “There’s more emphasis on the character of the Vineyard and ecology; we weren’t looking at that back then.”

The seventy-six-year-old Cabral said, “Most people who are as old as I am and who first became acquainted with the Vineyard in the late sixties and early seventies – we liked it very much. It was a wonderful place to live. There weren’t a lot of people; there weren’t a lot of rules.”

He added, “From the very first day that the Martha’s Vineyard Commission was put in place, the plan was to keep the Vineyard from being enormously changed over time – and of course, it has been enormously changed over time. I don’t want to call that a failure. I don’t think it is a failure. They’re doing their very best.”

Reflecting on the Island lifestyle he sought to protect, Amaral said he still enjoys hunting, fishing, raking quahaugs, and dip-netting for scallops with the caveat, “I can’t do it as fast as I used to.”

He said he’s proud of his contribution to the MVC. “Between the commission and the land bank there’s a lot of good that’s come out of both of them – you know and I know, when you look at the commission, they don’t make all the right decisions, but that’s the nature of the beast and that’s the way it goes.”