Ticks are a unifying force on Martha’s Vineyard. Year-round and seasonal residents, Island visitors, dogs, cats, horses – we hate ticks. These insidious arachnids (think spiders or scorpions, not insects) hide in vegetation along trails with outstretched legs waiting to grab on to a host creature that can provide a blood meal.

If that host is an unlucky human, he or she runs the risk of contracting one of many tick-borne diseases, a list that long ago grew to include more than the familiar Lyme and babesiosis. Depending on the species of tick – deer tick, dog tick, lone star tick – it now includes ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis, tularemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Borrelia miyamotoi, and Powassan virus. The lone star tick is also responsible for alpha-gal syndrome, a recently identified red meat food allergy.

According to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Nantucket and Dukes County, which includes Martha’s Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands, lead the state in hospital emergency department visits for tick exposures and tick-borne diseases. In 2021, the rate of tick exposure emergency department visits was 110.07 per 10,000 visits. The next highest rate was for Berkshire County in western Massachusetts with 18.93 per 10,000 visits.

Into the fray, enter Patrick Roden-Reynolds, who fills the new state grant–funded position of public health biologist. Working under the umbrella of Island Health Care in collaboration with the Vineyard and Nantucket boards of health, his broad mandate includes tick-borne disease education and prevention on both islands. He has a master’s degree in natural resource management from the University of Maryland, where his graduate work included a tick reduction project in that state.

He was vacationing on the Island last August when he learned about the new job. Speaking with the soft inflection of a native Virginian, he said, “It just seemed like a great fit.”

Roden-Reynolds takes over the responsibilities of Richard “Dick” Johnson, director of the Dukes County Tick Program. Since 2012, Johnson directed a multi-prong effort to reduce ticks and tick-borne illnesses through education, yard tick surveys, and advocating opening more properties to hunting to reduce deer numbers, a major element in the tick life cycle.

Johnson, sixty-nine, said the yard survey work is not as easy as it once was and he’s wanted to step back for some time, but was reluctant to do so until he knew the program would continue and was in good hands. He plans to do some environmental volunteer work on-Island and to concentrate on a less despised if not more cuddly aspect of wildlife. “I did the tick work because it needed to be done, but spotted turtles are my passion,” he said. “Now I’m going to go have some fun.”

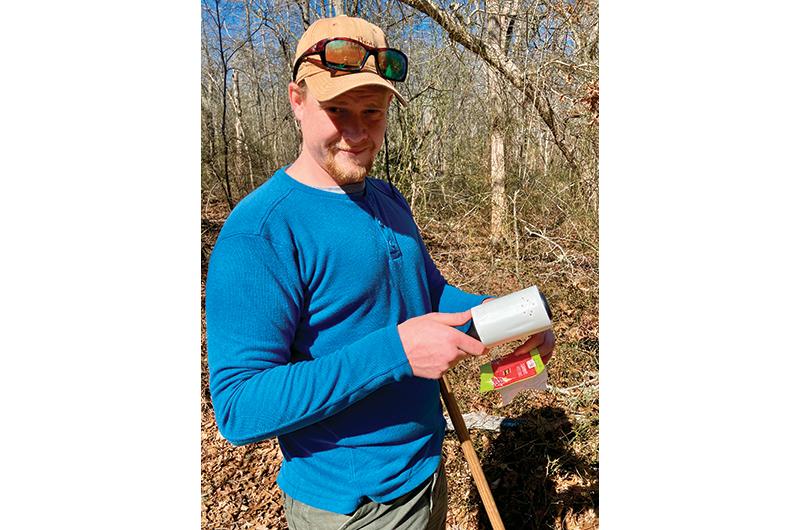

On a calm day in March with temperatures in the forties, I caught up with Roden-Reynolds and Johnson for a short walk along a trail in the Christiantown Woods Preserve in West Tisbury. Each man was armed with a white cotton flag that he dragged along the brush a few feet off the trail edge. We were not far from the parking area when we found our first tick clinging to the flag, an adult male deer tick. Roden-Reynolds placed it on a lint roller for safekeeping.

Roden-Reynolds said he’ll be building on the work of Johnson. While there is no single tick “magic bullet,” he said, there are smaller options that reduce the risk of a tick bite. These include wearing clothing treated with permethrin. Roden-Reynolds is also an avid hunter, and on Johnson’s recommendation he sent his primary work clothes and hunting gear to Insect Shield, a company that applies a long-lasting permethrin treatment for a per piece fee.

“Other than permethrin-treated clothing, I think the most important thing is to do a tick check,” he said. “You hear it over and over, but that vigilance and being aware that you put yourself at risk and might have picked up a tick is the best way to reduce risk.” He’s not talking about a once-over in the shower. “You have to check your whole body, every square inch.”

Around the home, both Johnson and Roden-Reynolds said, there are multiple ways to discourage ticks. They thrive in damp areas, so cleaning up leaf litter, clearing brush around the yard and other recreational areas, and pruning trees to let in more sunlight will help keep them at bay. Damminix tick tubes placed around the property perimeter can also help. The cardboard tubes are filled with permethrin-treated cotton balls. Mice, an important stage in the deer tick life cycle – and a reservoir of the Lyme disease bacteria – remove the cotton balls to make their nests, killing their attached ticks.

Jed and Jane Katch said Johnson conducted his first survey of their property in 2014. Since then, Jane said, they followed all of his recommendations, including placing tick tubes around the property perimeter and have seen a significant reduction in tick numbers. “We’re right in the heart of the tick universe.”

If you plan on working or recreating in the woods, Roden-Reynolds says to remember that ticks are more active when the humidity is high, and drying winds keep them in the shelter of leaf litter. But don’t be fooled by the temperature: cold weather offers no security. In the spring months, outdoor activities come with a heightened risk because ticks in the nymphal stage – tiny and hard to see – emerge and actively seek a blood meal after a period of relative winter dormancy.

“At this point, I just tell people that ticks are active all year long,” he said.

As if to prove the point, at the end of our short, chilly walk around Christiantown, the roller tally was sixteen adult deer ticks: twelve males and four females. Johnson said in late fall through the spring only the females are looking for a blood meal, ideally a deer, in anticipation of breeding and laying eggs. The males are looking for the deer in order to find a female to mate, Johnson said.

“They’re out, it’s a beautiful day for them,” he added.