When word came through to Lexie Roth that a previously uninhabited barn had become available for summer occupancy, the news hit like a crashing wave of relief. Roth had been searching for a summer rental with her partner, Eva Faber, for months, scouring Facebook groups and agent listings for a space, be it a cottage, shack, or apartment, to station themselves for the high season. The pair had recently begun a new business on the Island – a food truck called Goldie’s Rotisserie, that was making a splash in the local culinary scene. And with a lineup of fairs, fests, and private events to cater in the summer, the future looked bright – assumingthey had somewhere to stay.

Neither of the two was a stranger to the “Island Shuffle,” as the twice-annual migration of year-round Islanders from off-season to summer rental is not-so-affectionately known. Roth is a summer resident turned washashore in 2004, while Faber is an Islander from birth. “I was an expert at fitting everything that I needed in the back of my truck,” Roth recalled of her seasons on the move. “I would just work with what I got, buy a bureau or leave a bureau, and try to keep my roots as light as possible.”

No, this summer wasn’t anything new – it was just worse. So when, on the last day of their winter rental, the offer surfaced to fix up and move into an old, tiny post-and-beam structure on a friend’s property in West Tisbury, it was nothing short of a godsend.

“The only situation we found was our friend’s barn that no human had lived in before,” said Roth, describing the former storage shed’s swing door, windowless walls, and ladder entrance. With a little help from friends, the couple converted the shed into a living space – neither of the words very appropriate – adding a loft, an outhouse for a bathroom, a grill for a kitchen, and a hose for a sink. As with most summertime housing miracles, they made it work, mixing ingenuity with equal parts desperation and necessity. “It wasn’t even a choice. It was just like, ‘This is what we have to do because there’s no other option,’” Roth said.

For years – generations, even – a significant proportion of year-round Islanders have sustained themselves hopping from summer situation to off-season rental and back again. So common are the stories of riding out the summer months on couches, in camping tents, cobwebbed shacks, and school buses that the phenomenon has in some ways come to represent a rite of passage, inextricable from the fabric of year-round Island life.

But in the past, come winter there always seemed to be something available: a snow-crusted sublet, an empty house in need of a caretaker, a quiet summer cottage ripe for a space heater, an affordable Labor Day to Memorial Day lease. These off-season rentals, paired with a tenuous but existent assortment of year-round rental opportunities, created a landing pad of sorts for renters emerging from the hectic summer months, offering at least the appearance of a reliable rhythm for an unreliable shuffle.

Recently, however, even that modicum of predictability appears to have screeched to a stop. Not only has the already threadbare inventory of year-round rental properties disappeared under the pressures of a booming real estate and vacation rental market, but even off-season rentals are as rare as pulling a blue lobster from your pot.

As September tiptoed in, therefore, bringing shorter days, cooler temperatures and, increasingly, gusts of crisp fall air, it left Roth and Faber with a haunting question – what next? “It’s a full-time job every day: looking at listings every day, looking at classifieds, asking everyone. And for every single place I’ve lived, other than my [family’s] house, I’ve really only found things through word of mouth,” said Roth.

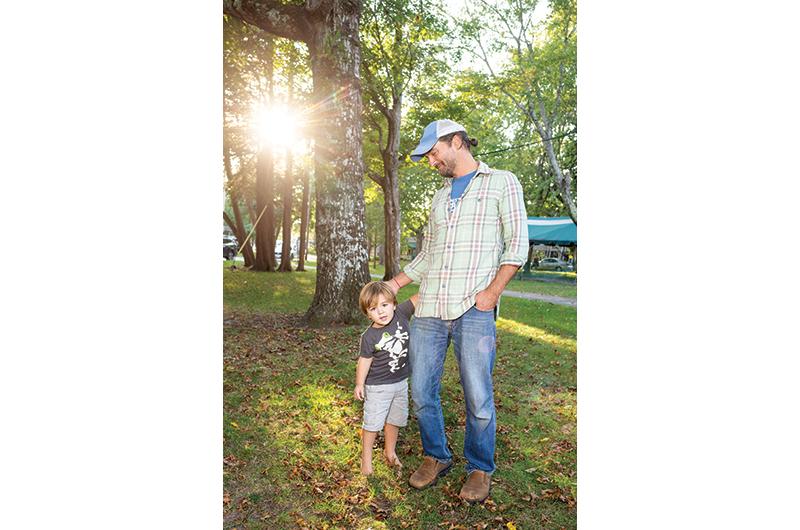

They are not alone, of course. Dave Ferguson, who shared a year-round rental in Chilmark with his wife, was forced to move out after they separated. Along with his son, Indi, who was eight months old at the time, Ferguson moved into his parents’ home and quickly began searching for a new spot suitable for the two of them. That was in January of 2020. He’s still looking for a home. “I honestly don’t know where else to turn and what I’m doing wrong,” he said. “When I started searching, I had standards about not constantly moving, some kind of regularity and familiarity for my son. But at this point it’s like, I don’t give a shit. I’ll take anything.”

Jake Meegan, an Islander and graduate of the Martha’s Vineyard Public Charter School, also moved back into his parents’ home while he searches for a year-round place. All his previous leased properties have since been converted into short-term rentals. Of the current options, Meegan reported seeing a $2,000 per month listing for a single bedroom.

The shortage trickles up the housing ladder, expanding into a web, as the kind of rental that might be a perfect solution for Meegan or Ferguson never even comes onto the market because it was only available through friends, family,

or pure serendipity. And for those who are lucky enough to find solutions, they can be patchwork. Liz Volchok and Tom Ellis had shuffled from a temporary arrangement in Ellis’s parents’ basement in Edgartown to a winter rental that ran high on rent before lightning struck in the form of a bare-bones, tiny cottage available year-round (and heated).

“It was a very lucky situation at the last minute, very much a miracle kind of scenario,” said Ellis, who grew up on the Island. The house has allowed them to stay near friends and family and in jobs that they love – Ellis at the Martha’s Vineyard Film Festival and Volchok, ironically, as a project development manager at Island Housing Trust, a nonprofit affordable housing developer. But with barely room to move, let alone grow, the couple is still uncertain about their future.

“We’re not looking for a ten-bedroom mansion. We’re just hoping for something that has a little bit more square footage so we can...move around,” said Volchok. “We collectively have never been more financially secure in any situation, and we still can’t find something that we can live in long-term,” she said, pausing. “My job is essentially to build affordable housing, and I am unable to find housing, let alone affordable housing.”

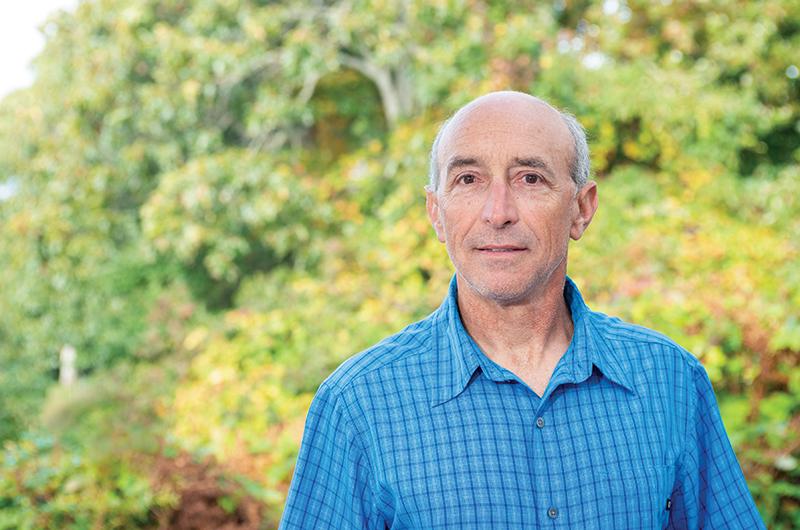

The shuffle, as we know it, traces back to the latter half of the twentieth century, when residential building and development picked up steam on the Island. “In the seventies and eighties, the shuffle predominantly was about homeowners moving out of their homes for the summer and paying off their mortgages,” said David Vigneault, executive director of the Dukes County Regional Housing Authority (DCRHA). Vigneault has been involved in affordable housing on the Island since he arrived thirty-four years ago. “There was a [type] of person who moved here because it was a beautiful, wonderful, funky place and there was work for anybody who wanted to call themselves a contractor. They bought cheaply, built cheaply, and began what we call the Island Shuffle.”

But by the 1990s, tides began to shift. Some attribute Bill Clinton’s presidential visits to Martha’s Vineyard with bringing new attention to the Island and kick-starting the explosion of tourism that eventually churned up real estate sales and summer-home ownership, as well as demand for summer rental properties at high vacation prices.

The resulting market forces and years of development had the seemingly counterintuitive effect of causing the overall supply of housing on the Island to explode while the proportion of it available for rental at non-vacation prices – both year-round and seasonal – shrank. “So, now, people can only get offseason rentals and they’re expensive, and the summer stuff becomes a combination of really expensive, or crazy creativity and desperation,” Vigneault said. “Suddenly people [are shuffling] to keep going to work, to keep raising their families and they’ve got nothing to show for it.”

In the subsequent thirty years the trend has only intensified, particularly in the past decade as an already booming vacation rental market has been accelerated by the advent of easy-to-use sites such as Airbnb and VRBO. Data provided by weneedavacation.com, a rental website that markets properties across the Cape and Islands, shows that bookings for desirable high summer season short-term rentals in the summer of 2021 were up 22 percent over 2019, while late May and June bookings were up 82 percent and overall annual booking rose nearly 37 percent over the same period. Go back a little further to 2017, and 2021 summer bookings have grown 23 percent, springtime bookings 96 percent, and overall bookings nearly 37 percent.

“New vacationers and the traffic numbers and the volume of inquiries has all increased quite dramatically over the last few years,” said Elizabeth Weedon, a spokesperson for the company. The site saw such high demand this summer, she added, that they struggled to supply properties, sometimes soliciting homeowners to see if they would rent. “I’ve worked here for thirteen years. I’ve never seen this lopsided supply and demand or demand this high.”

The rise of online rental sites is also changing how and to whom landlords rent, and not just because the platforms offer wider international markets. Landlords who once leased their properties to one or two tenants in a summer can now relatively painlessly rent to five or ten customers, stitching micro stays together, even into the shoulder seasons that were once not worth the effort. For homeowners who rent according to the market, said Weedon, it’s all pulling in a pretty clear direction.

For years Erica Jean Paul, a summer kid turned year-rounder, affordably leased rooms in her family’s cottage in Oak Bluffs to year-round tenants. A few bad experiences and an eviction process later, however, she gave it up and switched to renting short term using a platform called Vacasa.

“There is obviously the financial reward, [but] you’re doing it because it helps you save your family’s house that’s been here for three generations,” said Jean Paul, who felt the risks of legal action and other tricky situations made long-term renting unsustainable. Even beyond that, the new platform, which handles management and booking services for her, just made it easier. “If you’re not on the Island, it’s extremely difficult to manage tenants. It’s as simple as that,” she explained.

The fear of expensive eviction proceedings, damage, or otherwise not being able to access homes is widespread among homeowners. It’s a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy, as it’s precisely the lack of options that make some long-term tenants willing to push the boundaries: no one wants to be evicted. The fear is also reinforced by rental agents and platforms. Weedon said weneedavacation.com makes a point of warning homeowners about the risks of longer-term and winter renting. “In the summer, when somebody is here for a week, they barely unpack, they eat out. In the winter, it’s not somebody there on vacation. They’re living there; they’re using the kitchen; you have no control over the house. I think a lot of homeowners are reticent to take on those risks,” she said.

In the end, though, it’s mostly the money that talks. For many, the chance to make a month’s worth of off-season rent in just a week is incentive enough. Even property owners who for decades have provided year-round housing have to think about the incentives of working less and making more.

“I’m getting older and I’ve been doing this for many, many years and it’s not easy and not terribly profitable, especially at this point,” said Candace Nichols, who has rented a handful of properties year-round for more than twenty years. “I’m cruising toward retirement age, so things are changing now and I have to make some decisions.”

The decision isn’t always to move from long-term renting to short-term renting, of course. Perhaps the most salient factor of all in the disappearance of the shuffle is the rise in real estate prices across the board. Since the pandemic began, the Island, like many other resort communities, has seen an astronomical boom in real estate transactions of all kinds. In 2020 the Island recorded a total sales volume of $1.09 billion, shattering the previous all-time high record. Median home prices soared to $1.15 million, also a record. According to LINK, one of the Island’s multiple listing services, there were 518 properties on the market in the fall of 2018, which dropped to 469 on the market in the fall of 2019 and then plummeted to 288 in the fall of 2020. As of press time for this magazine, the number was 174.

As Island homes fly off the market at unprecedented rates and prices, rental properties are flying off with them – and they aren’t coming back in, either. “People who were trying to find a place to buy started buying crazily – and they’re not renting for the most part; they’re buying it to move into the house,” said Jim Feiner, a realtor who also chairs the Chilmark Housing Committee. “Homes that would have been rentable year-round, or even in the summer, have now trickled out and turned into owner properties and super high-end rentals.”

According to Vigneault at DCRHA, the office fielded an avalanche of calls from long-term tenants who had been suddenly displaced by the sale of their leased homes. Often the new buyers are not looking to rent long term. Shelley Christiansen, a landlord and real estate agent at Donnelly + Co., said there’s a term for the new class of home buyers: people buying “second primary homes.”

Even if the homes are bought as investment properties, the sky-high prices paid for them and the resulting mortgage costs all but ensures they are headed right to the short-term market. If by some chance they do stay in the long-term rental market, the rent is almost certainly going up. A housing needs assessment conducted by the Martha’s Vineyard Commission in 2020 showed that the average monthly rent on the Island rose from $1,180 in 2010 to $1,459 in 2020. On the other hand, the median income of renter households in 2020 was only $43,750. By that calculation, 40 percent of the average renter’s income goes toward rent.

But more important than the percentage of income going to rent is the percentage of houses available for rent. The population of the Island has grown more rapidly than its stock of houses, with the result that the Island community has shifted from primarily seasonal to something more evenly split between summer and year-round residents. The 2020 census data shows that 49 percent of Island homes are now seasonal, down from 57 percent in 2010. That shift from 9,644 seasonal homes in 2010 to 8,580 in 2020 suggests that as many as 1,000 potential winter shuffle rentals are no longer even possibilities.

Looked at another way, 4,065 people moved to the Island between 2010 and 2020, swelling the year-round population to 20,600. In that period, the Island added 342 new housing units, representing one additional housing unit for every twelve new residents. The result, according to a count by the Coalition to Create the MV Housing Bank citizens’ campaign, is that 700 year-round Islanders are on waiting lists for affordable rentals, while some 440 more are waiting to purchase affordable homes.

All of those forces were at work even before the pandemic struck – but when it struck, it struck like lighting. “We were down to a trickle of year-round opportunities. Winter rentals were getting more expensive, and the summer options were nuts. And then Covid hit,” said Vigneault. “What was a trickle across all fronts just basically went into complete shutdown, for all intents and purposes.”

Debates about housing on the Island are commonplace, but they often center around the particulars: much attention is paid in Facebook groups and around town to the granular issues of tenants and landlords, bad situations, and bad protocol. But with a degree of distance, it doesn’t take much to see that a patchwork of informal rentals and last-minute miracles wasn’t built to last, and the current crisis has revealed a much larger issue – a precarious system beginning to buckle.

Nor are suggested solutions in short supply. Plans for affordable or mixed-income housing units are currently in the works in every Island town, totaling around one hundred new units. The Coalition to Create the MV Housing Bank is preparing to take a third pass at a housing bank proposition that has failed twice. Nonprofits such as the Island Housing Trust are hard at work on affordable housing developments. The hospital has pitched a new seventy-unit senior living facility.

But there is nothing simple or easy about solving the crisis. Roadblocks of every variety – whether zoning and conservation restrictions, environmental capacity limits, NIMBYism, checks on development, or, at its ugliest, a poisoned well at an affordable housing development – await at each turn. The question of how to fix the system, and how fast, haunts.

“We’ve done nothing to incentivize owners to rent year-round so the rental market had been kind of like a beach eroding by the currency of wealth pouring into Martha’s Vineyard,” said Feiner.

In the meantime, the view from the beaches of rugged Aquinnah down to Circuit Avenue is beginning to shift, the landscape of the community already changing. Islanders, some with families dating back generations here, are beginning to plan their lives on the mainland. Many more have already moved off.

“We couldn’t afford to buy property on Martha’s Vineyard and no one had anything to rent…so we made the decision to move off-Island entirely. It’s a decision that was very difficult to make, but it was the only thing that we could do, so we did it,” said Brenda Mastromonaco, a resident who recently uprooted to Holyoke after almost forty years on the Island. Likewise, Diana Lin, an interior designer for the architectural firm Hutker Associates, chose to leave her year-round rental last winter when it went on the market and around-the-clock open houses made living there untenable. She found a studio after some searching, but with the stress of housing, she’s decided to leave the Vineyard for good this fall.

For others, like Ferguson, leaving altogether isn’t quite so simple. Moving off-Island would likely mean losing shared custody of his son. “I have to be here,” he said. “The only way I could leave would involve leaving my son and I wouldn’t ever do that, so I’m bound here, and I need to somehow make it.”

It’s a bitter pill. “One of the many things that the pandemic exposed is this dark, ugly underbelly of greed that really kicks the legs out from under the myth of this ‘strong community,’” Ferguson said. “I’ve come across places that are more than I paid when I lived in Brooklyn, and they don’t even have a kitchen and people are apparently renting these. I looked at one place and I thought, if [the Department of Child Services] somehow got wind of this, my child would be taken from me. I mean, it’s laughable.

“I don’t think it’s anything really exclusive to this Island, although this is a heightened place for income inequality and it’s right in your face,” he continued. “And it’s nothing really new. It’s been really exaggerated and exacerbated this past year and a half, but it’s been going on for decades.”

This past summer, the Island’s restaurants and retail shops limped through yet another season of worker shortages, while post office employees, bank tellers, and public safety officers couldn’t find places to live. The hospital rented hotel rooms for its part-time and summer staff. Long-time Islanders, always a group predisposed to say “You should have been here back when,” worried that the Island’s long-held reputation as a haven for creatives, self-starters, and free spirits is beginning to falter as young artists, musicians, chefs, and business owners – the very communities who have helped shape the Island’s character for decades – picked up and moved off.

“Next year, heading into the summer season, when some of the dust has settled, we will begin to have a sense of how much communities have been changed by the people who are not here,” said Vigneault.

“We essentially made a decision that if we don’t find anything by the spring of next year we’re going to reevaluate,” said Volchok.

“It’s an incredible place to be,” she said of the Island. But even with her and Ellis’s dream jobs here, the couple is “constantly gauging whether the struggle you’re going through is worth it.”

Roth, too, confessed she often has a daydream about an apartment in Western Massachusetts. It’s a sort of vague and golden dream – the top floor of an old, quirky house, a yard, space to grow. It was a strong network of friends and neighbors, the promise of good, steady work, and the chance to cook that drew Roth to the Island as an adult. That, and of course, it was home.

Roth and Faber recently lucked into a short-term rental: a sublet from a friend who is traveling during the winter months. Still, the hunt for something more permanent remains. Some days, she and Faber think about booking a ferry and hitting the road. They could take their food truck and their business and build a life somewhere else. But then, something always stops her.

“We could ship it off-Island if we wanted to,” she said, pausing for a moment. “But, you know, it’s Goldie’s Rotisserie – Martha’s Vineyard.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)