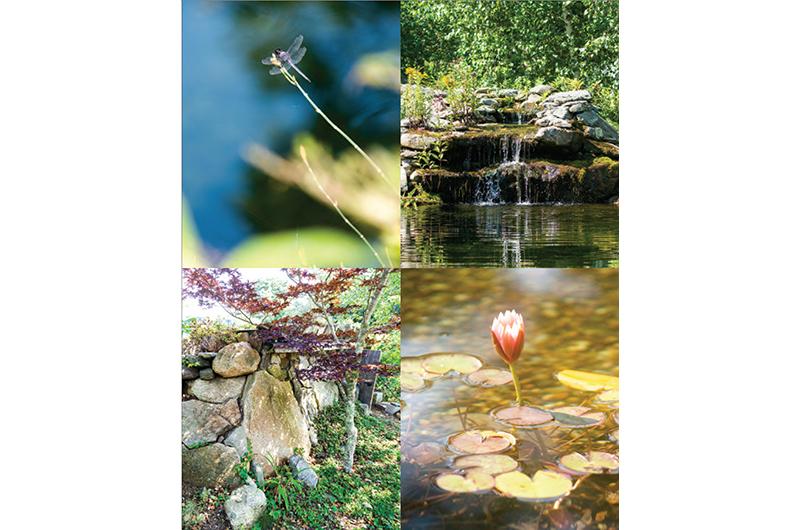

Daniel Whiting crouched over a glassy, clear body of water in West Tisbury, dipped in his cupped hands, and took a large sip. The motion sent ripples across the pond, bobbing an array of lilies and hibiscuses floating on the surface. A blue heron, perched on a rock behind a cluster of cattails, made three long strides and took off into a blue October sky.

“It’s a whole ecosystem,” he said, shaking off his hands and drying them on a pair of tattered pants.

But the ecosystem of this pond isn’t like most. It isn’t natural – at least, not natural in the sense that it was created only by the forces of nature. In fact, it isn’t even a pond. This man-made body of water is a swimming pool – a “natural swimming pool,” as Whiting and others in the trade call it – designed, built, and engineered to host the full spectrum of animals and wildlife native to the Island, from herons to flowers to the bipedal mammals reading this story.

“The difference is that you’re creating an ecosystem that’s engineered for swimming, but it’s still an ecosystem,” he said. “As soon as you build a water source, things are going to show up. The birds find out first and they tell everyone else pretty quick.” To be clear, Whiting does not actually recommend drinking the water, though advertisers of natural pool companies in Europe often boast that the water quality is better than most wells. “It’s basically drinkable water,” he said. “But at any given point, or any drop, you’re going to get different test results.”

Whiting owns and runs Whiting Construction, a relatively small and versatile Island-based construction company specializing in ground-up developments, home additions, and historic restorations. It’s a trade he has been involved in almost as long as he has lived on Martha’s Vineyard. The company was started in 1972 by his father, Jonathan Whiting, who arrived on the Island during the construction boom in the early 1970s. His son, as he says, “was raised with a hammer in [his] hand.” And when his father retired last year at the age of sixty-six, Whiting took the helm.

Like many second generation Islanders involved in a family trade, Whiting decided to steer the company in a different direction. About a decade ago, he discovered a passion for creating natural pools and established an offshoot of the construction company: Next Generation Natural Pools. The specialized trade has a long history in Europe, he said, but in the United States it’s more of a niche market. His company is the first and only natural swimming pool firm based on the Island.

The science underpinning the pools is complex. It involves underwater retaining walls, plumbing manifolds to flush the water, microbes to eat the buildup of bad bacteria and leaf matter, and mathematical equations to balance each part. But the result is a simple concept: where conventional swimming pools use chemicals such as chlorine to sterilize water, this process aims to naturally and autonomously purify it.

“The old school way of thinking, when it comes to things like this, is: if you don’t understand it, kill it. That has been the routine. And I think that applies to a lot of things, pools specifically,” he said. “I just hope we can recognize that, if we look close and take time to understand things, it doesn’t have to be this way. It’s easy to sterilize water, but it’s possible to purify it.”

Natural pools aren’t cheap compared with conventional swimming pools; prices start at roughly $200,000. So far, Whiting and his crew of three full-time workers have built three natural pools, with another two currently being built. The trade is beginning to find its place on the Island. It wasn’t easy, he said. He had a lot to learn before he could turn this passion into a viable enterprise. But he was determined. For him, it’s a mission driven by a thirst for understanding the natural world, a deep appreciation for the aesthetics of design, and a personal reckoning with the failures of scientific progress to heal the environmental degradation that it caused.

On weekends during high school and through the summers in college in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Whiting worked in construction alongside his father. He knew he would eventually enter the family trade. But he also harbored a natural resistance to it. He preferred spending his time outside: fishing, swimming, getting lost in the woods and lost in his mind trying to understand the elements of nature that surrounded him on the Vineyard. “I was always happiest being outside, learning about nature rather than being in a classroom,” he said.

He attended Green Mountain College, a small school in Vermont with a focus on environmental studies, where he augmented those studies with a minor in philosophy. “I wasn’t raised with a religion, so nature is kind of where I turned for answers,” he said. There was something between those two fields of study, nature and human nature, that he was searching for. Trying not to be defeated by haunting visions of a world that seems to be sleepwalking toward its demise, he grappled for a long time to understand how he could play a role in shaping a more environmentally conscious future. “I just felt like something had to change. It was frustrating not knowing what that really meant.”

In his final semester at college, Whiting was uncertain what the future would hold. He was slated for another summer of construction when a friend of a friend offered a different prospect entirely: delivering a sailboat across the Atlantic Ocean. “The plan was to graduate, but for me it wasn’t about the diploma. It was about knowledge, and this was a once in a lifetime opportunity.” Three weeks before graduation, he packed his bags and flew to Portugal. “I just dropped everything and I went,” he said.

With their sights set on Newport, Rhode Island, the crew voyaged across the Atlantic in a fifty-two-foot sailboat, which Whiting said felt pretty small glancing around at the vast swells of open ocean, thousands of miles from shore. The plan was to take the trade winds down and the Gulf Stream back up, but for a time, likely while his classmates were receiving their diplomas, they spent days bobbing around in the doldrums. With the boat becalmed, Whiting, mostly to stay sane, spent time reading, fishing, and, yet again, contemplating his future.

When he returned to the Island, he settled into working for his father’s construction company, building houses. He bought a sailboat, a thirty-six-foot fiberglass Albin with no engine and a teak deck, and continued his habit of learning about nature and philosophy through reading and observation. His life, it seemed, was running a steady course.

That is, until a friend passed him a copy of German spiritual teacher Eckhart Tolle’s book The Power of Now. “I read the book and said, ‘This is for me.’” The winds had shifted again, and Whiting decided to travel to Hawaii to attend a spiritual retreat with the author. As theorized in the book, things began to fall into place once he began to act. One friend had unredeemed frequent flyer miles, another friend had a place to stay.

But the most important moment of the journey occurred outside the group meditation, yoga, and even beyond Tolle’s guided seminars. Whiting was driving through the lush, mountainous roads of Maui when he decided, somewhat randomly, to pull off and go for a hike. It was on that hike that he came across a simple metaphor that seemed to capture what he had been searching for: a water lily. “I was seeing it reflect back at me, and that stuck with me,” he said. “I just couldn’t get it out of my head. I came home, and I wanted to figure out how I could keep that in my life somehow. So I tried to grow it in my fish tank. When I realized that wasn’t going to work, I sold my boat and built myself a pond in the backyard.”

With the money from his boat, Whiting took two months off of work and bought the supplies for his first natural pool. He dug out the eleven-by-nine-foot hole by hand and studied water flow, microbes, and water purification. It was a self-taught crash course in the science of aquatic ecosystems. “I had so much fun doing it, learning along the way, I decided to add these ponds and water features to another thing I can build for people,” he said. When he got his first customer, he hired a consultant from western Massachusetts to help hone the mathematical formulas required to perfect the craft.

The natural pool he created in West Tisbury for Doug Plotkin holds a special meaning to Whiting, as he also completed the renovation and additions on the home. Plotkin is a retired management consultant who bought the property six years ago. At that time, what became the natural pool was a man-made pond. It was essentially a hole filled with water: a closed system with a liner in the bottom that required sanitizing pellets to be dumped in every spring.

“It was pretty from a distance, but when we got up close it wasn’t very pretty,” Plotkin said. “The previous owner said he went swimming in it every day. Everyone kind of looked at him, and no one wanted to go in.” It took two loads of a septic truck to remove all the debris, bird waste, and decaying leaves caked along the bottom. Next, the pond was drained and Whiting’s filtration system was added. It included specialized plumbing, aerators, skimmers, and multiple layers of gravel. Finally, the pond was refilled. For the finishing touch, a diverse ecosystem of plants was added.

“Now we really do swim in it almost every day,” Plotkin said.

Whiting said his company is beginning to gain traction on the Island, and his drive to learn from nature hasn’t subsided. “With nature, it’s infinite in terms of things to learn. I’m learning what I don’t know every day,” he said. He is still hoping to learn how to make a water lily – the tropical kind that inspired him in Hawaii – last through the harsh New England winters.

In the meantime, he’s more optimistic that the company will continue to grow and that his small but radical rebellion of working with nature instead of against it will continue to be understood.