Lew French is used to being called many things: stonemason, craftsman, designer, builder, spiritual seeker, vegetarian, author, teacher.

But whatever you do, don’t call him an artist.

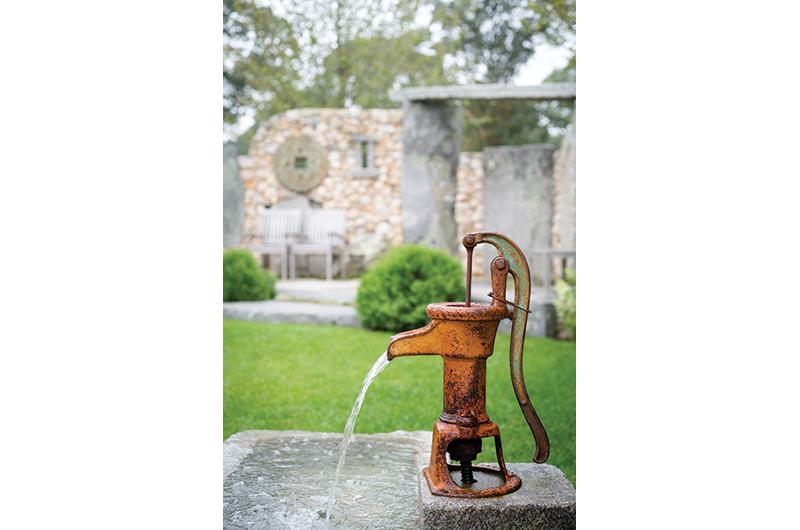

“Work is about producing,” the sixty-three-year-old French proclaimed, minutes after we met in the Rose Styron Garden at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in Vineyard Haven. French was overseeing finishing touches on the outdoor installation, only the second public project he’s agreed to take on over the course of a career that’s spanned the past four decades. “You can call it art; you can call it whatever you want. But the bottom line is, how efficient are you? How much work can you produce at the end of each day?”

With decades of custom projects under his belt – from fireplaces to stone walls to sprawling eight-acre landscape installations – French knows a thing or two about efficiency. In recent years, off-Island commissions have taken him from Vermont to Lake Placid, Bar Harbor to Brazil. His most recent book, Sticks & Stones: The Designs of Lew French (Gibbs Smith, 2016), features these and other far-flung installations, with photography by Islander Alison Shaw.

Moving beyond hearths and chimneys, lately French has been working on grander scales while continuing to maintain his trademark utilitarian approach. The fact that his work, big or small, tends to be appreciated by clients, fellow craftspeople, and galleries (such as the Granary and Field Galleries in West Tisbury, where a few of his pieces are on outdoor display) as “art” is just something French has had to live with. He’s learning.

“I’ve been very lucky,” he said, reflecting on a long career of working with stone and the many awards, accolades, and bits of favorable press he has collected along the way. At thirty-eight years old he was featured in The New York Times; pieces in Architectural Digest and House & Garden, segments on CBS Sunday Morning and NPR, and a 2015 induction into the New England Design Hall of Fame would follow.

Born in the small farming town of Zumbrota, Minnesota, French learned the value of hard work at home. His mother taught school. His father worked as a lineman for an independent phone company and would often enlist the young French to help with projects around the house. “My dad gave me a sledgehammer in our old house and told me to knock down a wall when I was twelve,” French remembered. “We had to pour our driveway out of concrete, so I learned how to mix concrete. Then we poured concrete for a basketball hoop. You didn’t hire somebody to do that. You didn’t have the money. You just did it.”

Despite an inquiring nature and a deep love of reading, French wasn’t much of a student. “I hated high school,” he said. “Every minute of it.”

An all-conference football player, he stayed enrolled only to be eligible to play in games. “I lived for sports,” he said. And if it hadn’t been for a vocational program introduced at the beginning of his senior year, during which students were given the opportunity to build an entire house soup to nuts in exchange for a passing grade, he isn’t sure that he would have made it to graduation. “That was the thing that saved me,” he said.

Never thinking he would follow a college track, French was surprised to be accepted into a vocational program for carpentry in nearby St. Paul. But after his senior year of high school spent learning every facet of home building, on top of the years he’d spent “apprenticing” with his father, he was dismayed to find himself back to basics. “I was there for three months and I said, ‘This is ridiculous,’” he laughed. “I had just built a house and we were making these little boxes. It was a three-year program. I didn’t have the patience.”

He moved back home and cobbled together a crew of his own, setting off on a self-guided immersion program in carpentry studies. With a minor in ego management, French soon learned how much he had to learn. “I was lucky enough to have these three or four retired older guys,” he said of his first ragtag crew of local carpenters. “I was their boss, but really I was their apprentice.”

One old-timer in particular made an impression on him. Part of a Scandinavian crew that had traveled the world working together for decades, Leonard Lundgren was in his seventies when French brought him on. “He was very quiet, very gentle,” French said. “He smoked a pipe. He was always pleasant.”

Each day Lundgren would come to work and the eager, frenetic French would see himself as handily outpacing him. “I’m all over the place, and he’s just….” French imitated the older man, pipe in mouth, deliberately hammering a nail. “Every motion had meaning. And I learned very quickly at the end of the day, he was outworking me.”

It was also with Lundgren that French got his first introduction to working with stone. His father was building a new family home and French helped Lundgren with the fireplace. Something about the process – specifically, the energy of the stone – spoke to him. “I knew immediately it was what I wanted to do,” he said. “It was there, but I wasn’t ready.”

After a few more years of working construction in Minnesota, and a tip from a friend about a small island off the coast of Massachusetts, French relocated to Martha’s Vineyard in 1983. He moved with a single goal in mind. “I came here with one purpose,” he said. “To do stonework.”

Years of intense study of the history of stone walls and masonry, combined with a strong affinity for natural materials (he often incorporates pieces of driftwood into his work), led French to develop opinions about an ancient practice that has been a part of the Island’s landscape for centuries.

“Stone walls around here fall under the dry stack category,” French said of the rambling walls in Chilmark he was drawn to in his early years as a Vineyarder. “They’re farmers’ walls,” he said. He went on to explain that the climate and ecology of the Island gifted farmers with freshly unearthed stones each year after the frost. “Every spring the farmer had to go out and dig up the rocks, because a farmer wants clear fields.”

And all of those rocks had to go someplace. Why not a wall? “They’re boundary walls,” French said. “They’re not meant to be aesthetic. They have an aesthetic beauty, but it only goes so far.”

Less appealing to French than these early, rudimentary walls is what came next, when masons began to realize that with a little mortar and a lot of cutting, any rock could fit any place, in just about any way. This was the brand of masonry French said he often encountered when he first arrived on the Island.

“Most stonework done at the time used mortar joints,” French said. Taking cues from the dry-stack look he found and admired in the old farmers’ walls, French began to experiment with letting the shape and contours of the stone itself dictate the way a piece came together. Working without mortar or making any major cutting or chiseling, he discovered that natural stones lay at rest in a pleasing arrangement. “Our mind works where if things are at rest, it makes us feel more comfortable,” he said.

Thus began his love affair with the medium, and his never-ending quest to find just the right stone, taking into consideration texture, shape, and patina. For years he has traveled to abandoned granite quarries in Maine and New Hampshire, hauling back truckloads on truckloads of weathered rock to be used for client projects or stored for later. His favorites are often the stones that have been cast off and forgotten, broken pieces that wouldn’t conform to the manufactured aesthetic that relies upon clean squares and rectangles.

“These are garbage pieces,” he said, gesturing to two unique slabs of granite that feature prominently in the museum installation. “Pieces that broke incorrectly. To me they are gemstones. I pick them for what they are.”

French had been toying with the idea of slowing down professionally in 2019 when the Martha’s Vineyard Museum approached him about the Rose Styron Garden project. A group of donors wanted to fund a public space on the museum grounds to honor the poet and human rights activist, who is a longtime resident of Vineyard Haven.

“I’ve been working like a dog for many years,” he explained. “It’s very physical work.” A vegetarian diet and a daily routine of stretches have helped to keep him limber (“I’m not Hercules, but I’m flexible”), but after a decade of intense travel and large-scale installations, he was ready for a break. Yet the offer from the museum was irresistible.

“They promised me the moon,” French laughed. “They gave me free rein.”

Stever Aubrey, who was the chair of the museum board when the garden was commissioned, said that the idea of incorporating French’s work grew out of common interests the stonemason shares with the garden’s namesake. “We wanted to create a community space that was conducive to reflection and discussion around arts and humanities,” Aubrey said.

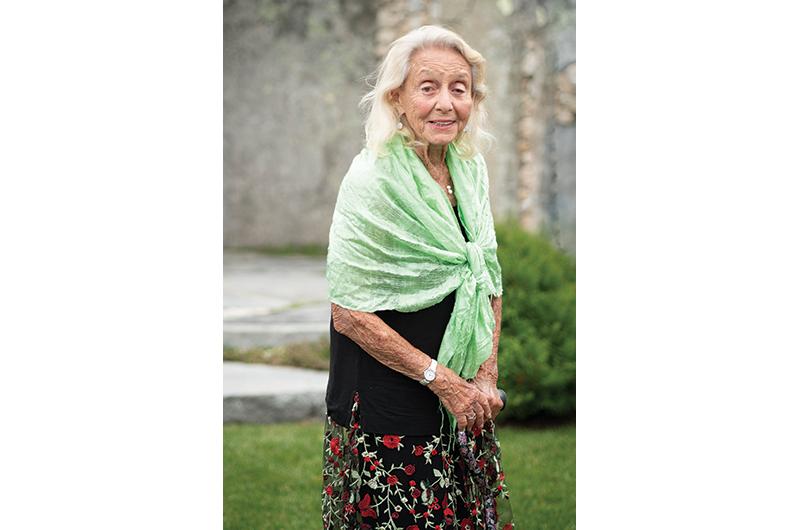

“Lew French is the poet of stone architects,” said Styron. “Needless to say, I’m over the moon since I have watched him construct the museum garden so quirkily, generously named for me.”

With full artistic license, step one for French, as it always has been on projects of this scale, was to walk the space and get a feel for what could work, where. “It’s important for me to develop something that makes me feel comfortable,” he said.

With only four predetermined corners and the vague idea of a rectangle as his guide, French began to explore his outdoor canvas. Eventually, he felt drawn to a corner of the space nearest to the museum. He envisioned sitting in that corner, waiting to meet friends. “This is how it starts,” he said. “I’m having a cup of coffee, I’m meeting my friends; I’m looking all around.”

The spot became a bench, which became the foundation for the garden’s perimeter. He continued to consider the project from all angles – walking out of the museum’s cafe, approaching from the parking lot – and let the final form evolve naturally as he started to put the stones together, one section at a time.

“The gift and the burden of stonework is that it takes so long to do,” French said. “I have a lot of time to think. I’m doing one component, and I’m thinking about the next component, and the next. I have time to absorb it, to understand it, to be a part of it.”

Individual components grow out of a feel French develops for a space, or a desire to feature and highlight a particularly special stone. “I’ve learned very quickly that my best work is to leave the material alone. When I’m doing these things I’m trying to let nature speak for itself,” he said. “Nature is a good teacher. If you try to be blank in nature, you absorb things. You take things in.

“There was no plan here,” he continued, looking out over the array of stone benches, sculptures, and walls. Between them, rough landscaping had been started, to be finished, with some delays due to the pandemic, over the course of the next two seasons with lots of volunteer help from the Martha’s Vineyard Garden Club. Today the plantings and sod are well established, a living and malleable complement to the months of hard labor, thoughtful contemplation and, with apologies to the craftsman, the indisputable artistry of the stone.

“The plan was a rectangle.”

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)