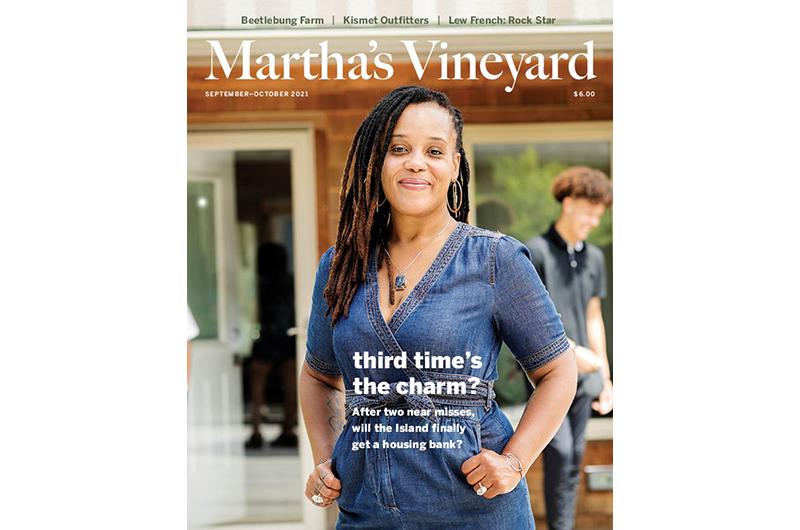

Lucy Morrison is no stranger to the Island Shuffle, the seasonal migration from one rental to another. In fact, as far as seasonal shufflers go, she’s something of a legend. Born on Martha’s Vineyard and now in her mid-thirties, by the time she was four years old she and her mother had moved roughly ten times, from town to town, packing up and trading in one short-term rental for another. Last year alone she was forced to move twice: first, when one lease ended in January, and all that she and her partner, musician and sound engineer Andy Herr, could find in the dead of winter was far from year-round. “It was a three-month lease,” Morrison said, still disbelievingly. “I didn’t even know that was a thing.”

Despite the near constant upheaval, Morrison knows she is one of the lucky ones. When all else fails (because when it comes to Island real estate, it often does), she has family to take her in. And last summer, after the lease-that-was-barely-a-lease had expired, she and Herr were thrilled to stumble into a year-round situation (at least for now because of the pandemic) when friends informed her they’d be converting a family home into three long-term rental units.

She knows, too, that her struggle to find year-round housing is hardly unique, which is, in part, what motivates her to do something – or lots of things – about it. When not busy at her day job at the Martha’s Vineyard Commission (where affordable housing frequently tops the list of hot-button priorities), she serves as chair of the Edgartown Planning Board, and is the at-large representative to the Duke’s County Regional Housing Authority, a special designation created for those who have lived in all six Island towns.

Most recently, Morrison and a growing group of concerned and, increasingly, younger citizens have been lending their skills and lived experience to a new initiative that aims to empower Islanders of all ages to step up and make the fight for stable and reasonably priced long-term housing their own. Working as the Coalition to Create the MV Housing Bank, and led by a steering committee of sixteen volunteers and a paid campaign coordinator, the CCMVHB – informally known as the coalition – was formed in early fall of 2020, and through methodical outreach, grassroots organizing, and significant legislative liaising, has slowly grown into a movement with a real chance of succeeding where previous similar efforts have faltered.

The coalition’s goal is simple: to create a housing bank (for an easy parallel, think: the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank Commission, for humans) supported by a reliable funding stream that allows for the construction of more affordable housing units for more Island residents. But how would a housing bank operate, who would fund it, who would maintain it, and who stands to benefit from bank-approved projects long term? These are among the questions the coalition’s steering committee has been working to explore – not to answer definitively for themselves, but to share in conversation with the Island community so that answers can emerge collaboratively, thoughtfully, and organically over time.

This is where a handful of statistics would be helpful, though they are notoriously difficult to verify reliably. Over 700 year-round residents and their families are waiting for affordable rentals, including 210 children, according to the coalition’s count, and another 440 year-round residents are currently on waiting lists to purchase homes within their financial reach. Harder to know is how many Island families have not even been able to get on the waiting lists, a not uncommon circumstance for those with “good” jobs and salaries but still no ability to crack into the market. And no one knows how many professionals, tradespeople, and essential workers, mothers, fathers, daughters, and sons were forced to leave the Island – in many cases the only home they’ve ever known – due to insecure, unaffordable, or just plain nonexistent housing alternatives.

Even before the pandemic, the lack of housing felt like the number one topic of conversation among the working year-rounders, whether employers looking for help or job holders looking for roofs. Indeed, the refrain that “it’s always been tough” is one of the standard arguments of those who oppose efforts to create sustainably affordable housing. But if there’s one thing the last year and a global pandemic have taught us, it’s that there is no “normal” anymore. And nowhere is this more apparent than in the Island’s housing market, where the median home price, already well over $800,000 in 2019, by November 2020 had skyrocketed to $1.2 million and is now thought to be closer to $1.3 million. Suffice it to say that no year-round Islander was surprised by The Boston Globe’s recent headline “From Fire Chief to Mail Clerks, No One Seems to Be Able to Find Housing on Martha’s Vineyard.”

And so, in September of 2020, just about halfway into the year of Covid, masks, and quarantines, longtime housing advocates John Abrams and Doug Ruskin had an idea. As veterans of the decades-long push to pass some version of affordable housing legislation at both the state and local levels (including, most recently, a failed attempt at a similar housing bank effort in 2019), Ruskin and Abrams had seen the housing problem go from bad to very bad to worse. They convened a meeting on Zoom in November of roughly thirty affordable housing stakeholders and shared their idea for the rebirth (and not just the rebranding) of an Island housing bank campaign, one that would rely less on quick, behind-the-scenes moves and statistics, and more on meeting people – real people – where they were.

The carefully considered approach that evolved from that first meeting was not just intentional; in a way, it was the point.

“The ask was: who wants to participate in and potentially be on the steering committee of another effort to create a housing bank,” remembered Arielle Faria, who, along with former Martha’s Vineyard Community Services executive director Julie Fay, co-chairs the coalition’s steering committee. Faria, who lives with her husband, Augusto, and two sons in West Tisbury’s Scott’s Grove, a nine-unit affordable housing development built by the Island Housing Trust in 2018, watched the 2019 housing bank initiative closely and felt the time was right for a second chance. As someone with both personal and professional experience navigating the complex network of affordable housing on the Island, she felt called to play an active role.

“It was just like, you know what? I think this is the next step. Not to say that it’s the only step, but I’ve always believed that doing something is better than doing nothing.”

With co-chairs and a steering committee in place, the coalition brought on Laura Silber as campaign coordinator. Silber, who has experience in advocacy as a longtime member of the Martha’s Vineyard Island Parents Advisory Council on Special Education, and is a founding member of the social justice group We Stand Together/Estamos Todos Juntos, began to investigate what was happening in the affordable housing arena at the statewide legislative level.

The answer was: a lot. Cape and Islands state senator Julian Cyr and Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket state representative Dylan Fernandes are both involved in efforts to pass various bills and resolutions working their way through the state house that are aimed at creating a new funding source for municipalities looking to fund affordable housing efforts. And the Cape and Islands are not alone: with affordable housing now virtually a statewide crisis, legislators from the Berkshires to Provincetown are feeling pressure from their constituents to take action.

The basic idea behind the various proposals moving through the legislative process is to allow cities and towns to enact real estate transfer taxes dedicated to funding affordable housing. The bills differ principally on at what sale price the tax will kick in, as opponents – led by the real estate lobby – argue that additional taxes on real estate sales at the lower end of the market would make it even more difficult for first-time home buyers. Whether the final bill out of Beacon Hill has a fixed price above which the tax is paid (say, 2 percent on the cost of a home that sells for more than $1 million) or is calculated through a formula that takes account of local median prices remains to be seen. Given how high real estate prices are on the Island, however, even if the threshold is set high by statewide standards, the potential for revenue generation on the Island is good.

That the impetus for renewed action is coming in part from Beacon Hill is somewhat ironic. A similar proposal to enact a land bank–style transfer fee to fund housing on the Vineyard made it through town meetings once before, in 2005, only to stall out at the state level in the face of heavy lobbying from the Massachusetts Association of Realtors.

Most importantly, perhaps, towns will not be permitted to enact these new fees for any purpose other than affordable housing. It is, said Silber, “a new revenue stream that can’t be used for anything else.”

The potential for a dedicated source of revenue is a major turn from the 2019 proposal on the Island. Back then, Ruskin, Abrams, and others were spurred to action by the state’s enactment of a short-term rental tax. They argued that some of the revenue from the tax could be used to fund a housing bank, but the resulting petition failed to pass in all six Island towns. “In every town, infrastructure is already stressed,” Silber said. “The towns felt like they needed the additional revenue to support that. This [proposal] was seen as a diversion of funds.”

With a new(-ish) and more palatable funding engine potentially accounted for, Silber and the rest of the nascent coalition moved swiftly to open communication with town officials, including all six Island affordable housing committees, private developers such as the nonprofit Island Housing Trust, as well as regional bodies including the Dukes County Regional Housing Authority, the land bank, and the Martha’s Vineyard Commission. “Buy-in was essential,” said coalition co-chair Fay. “We started back in January, attending select board meetings, [financial committee] meetings, and planning board meetings in each of the six towns, and listening to what town representatives on all of the boards had to say.”

From the land bank, the coalition received early welcome news. It would be willing and legally permitted under its own charter to collect the transfer fees, which it already does for itself. This should enable a swift and seamless start-up – assuming the proposed housing bank is able to jump through the necessary legislative hoops required to be written into law. Which is, of course, a McMansion-sized assumption. Though individual Island towns could theoretically set up their own transfer taxes and housing initiatives as soon as the state passes enabling legislation, creating a regional bank, which everyone agrees would be far more efficient for the Island, would require agreement on terms from all six town meetings followed by additional enabling legislation from Beacon Hill.

The earliest the various state-level proposals are likely to be decided upon is near the end of the legislative session in July 2022, which is to say after town meeting season in the spring. But the coalition is not going to wait for final word from Beacon Hill before bringing the issue to the towns.

“We want to build the bucket,” said Silber, “so that it’s ready to go when the funding becomes available.”

How a housing bank might invest that funding is not yet settled. The website mentions building new housing units and accessory apartments, and offering down payment assistance for market price homes, but, said Silber, “There’s no reason for a housing bank to duplicate services.” She noted that the housing bank has received endorsements from many of the existing groups and organizations involved in the housing issue, organizations it does not aim to supplant or make redundant but to support long term.

The earliest the Island could see its own state-approved housing bank, therefore, would be midsummer of 2022. But coalition members are hopeful and committed, buoyed by signals from the governor and his administration that affordable housing has risen as a chief concern across Massachusetts. This is due in part to the pandemic, Silber said, but also to a growing appreciation for insecure housing as a “root cause” of other public health concerns.

“Housing is a public health issue,” Silber said, adding that a lack of secure housing is used by social workers and statisticians to predict unfavorable outcomes on substance abuse; school dropout risk; poor health outcomes among children, teens, and adults; and depression, among others. “It’s a baseline risk factor for almost every health issue you can imagine.”

This shift in awareness may be happening at the state level, but here on the Island, there remains some deep pockets of resistance, firmly rooted in the way that Islanders perceive the question of who deserves to live here, and how.

“People here are so numb,” Silber continued. “Culturally, we don’t tag the Island Shuffle as housing insecurity.” In other words, it’s become easy to accept situations like Morrison’s – moving in and out of short-term rentals, filling gaps with family support – as just part of the social contract Islanders sign when they choose to live here. The success of an initiative like the housing bank depends not only on complicated legislative maneuvers, but also on the collective acknowledgment that working adult professionals who live in three rentals a year, camp out in a relative’s basement, and/or bunk on a friend’s boat in the summer may not be “adventurous” or “shuffling,” so much as they are, demographically speaking, homeless.

Silber and the coalition feel that this shift in perception is critical to a deeper understanding of what the crisis looks like on-Island today. While the conversation may have started as a “low-income” issue – a way to provide affordable housing for community members with income at or below the state and local average – it must now grow to include a far larger swath of Island residents, including skilled professionals.

“We need to see the housing crisis in the context of infrastructure and economic stability,” Silber said. “We hear people framing it sometimes as ‘Not everyone deserves to live here, and if you can’t, you should move off-Island.’ We’re at a point where if everyone who can’t afford to live here moves off-Island, our infrastructure will collapse because we would have no workforce, including no professionals, no medical workers, no firefighters, no teachers.”

But will those same citizens show up at town meeting to support a housing bank? Perhaps the most critical task now before the coalition is speaking to the hearts and minds of everyday Island community members, educating them as to the housing bank’s potential, while inviting them to become involved in ways that may be comfortable for some more than others.

“It’s intimidating,” Silber said, remembering her first forays into the world of advocacy and grassroots organizing. And yet, “learning how to have your voice heard is incredibly empowering. Once you start attending meetings and realizing how much community input influences governmental decisions, once people understand how to access, and that they can access comfortably, then you see things start to shift.”

Caitlin Burbidge, a recent Island transplant with a background in affordable housing advocacy in the Greater Boston area, considers one of her roles at the coalition as encouraging Islanders of all stripes to share their stories and struggles with insecure housing as widely and as often as possible. Formally a “town ambassador,” as well as a member of the steering committee, Burbidge calls community organizing her “heart work,” and, like Morrison, feels lucky to have had the family support that was necessary for her to be able to move to the Island full time to do it.

“It is a long-term goal of mine to get more young people and young parents involved at town hall,” Burbidge said, recalling a scheme she and some friends had a few years back to have T-shirts printed that read “Make Town Meeting Cool Again.”

She and other coalition members agree that in order to invite new participation at the grassroots level, access is key. “We have to reach people and support them in order to be able to get them to meetings,” Burbidge said. Some of those outreach efforts are already in place: coalition co-chair Faria’s husband, Augusto, provides Brazilian-Portuguese translation for all coalition print materials, and real-time interpretation services were provided at the community listening sessions held earlier this year. The coalition also stresses the importance of providing childcare for in-person meetings, and says that offering multiple entry points for access and encouraging inclusive participation are touchstones of its campaign.

“Our community is diverse, and our representation should be just as diverse,” Faria said, noting that representatives have been engaged from the Island’s Brazilian, Black, and Indigenous populations. “It’s a challenge in the sense that under-represented groups are often under-represented because they don’t always have the time to participate in the way that more privileged people can.” To some degree, Faria faces the same challenges of wearing multiple hats; in addition to serving as co-chair she continues to work for the Edgartown Housing Trust and the Edgartown Affordable Housing Committee. “It’s not an easy thing because I do still have a full-time job and two children,” she said.

Burbidge added that while community outreach across all demographics is paramount, she’s aware that there’s always more to be done. “We are aiming to be open to our blind spots,” she said. “If you see an area where you can improve, if people aren’t feeling seen or heard, we’re open to that. When we hear negative feedback we move towards it, in order to understand it.”

So far, coalition members have been pleasantly surprised by participation levels, crediting factors such as the necessary rise of Zoom meetings – allowing, for example, people with young children to attend meetings without having to arrange and pay for childcare – and an active social media and web campaign, led by Island millennials Abbie Zell and Zivah Solomon.

Solomon, who manages Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter pages for the group, says that it was, in part, the abundance of online activity she was seeing in housing-related groups that propelled her to lend her experience in marketing and internet strategy to the campaign. “Nearly every day you’re seeing posts saying something like, ‘I’m going to be homeless, I have two kids, I’m living in my car,’” Solomon said. “These people are all around us.”

In the end, it may be the energized and coordinated participation from younger generations that ultimately make the difference for a housing bank this time around. “People are coming of age on the Island and realizing they can’t afford to stay here or find stable housing,” Solomon said.

Faria agreed. “I think our generation is starting to realize that we are our parents’ age,” she said. “We’re grown now. We’re the ones that are in charge of creating our future.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)