As everyone on the Island surely knows, Oak Bluffs has a long history as a community that welcomed persons of all races, particularly African Americans, to its neighborhoods and beaches. It’s a tradition that dates back to the earliest years of the community’s existence, in the decades before the American Civil War – long before the vast majority of other American summer communities (including some on Martha’s Vineyard, it should be said) opened their hearts and doors. And yet the apocryphal wisdom among many in the town has long been that Black people were not always allowed to live and own cottages in the historic heart of the town, the Martha’s Vineyard Camp Ground. It was, in some ways, the skeleton in the closet behind the gingerbread façade.

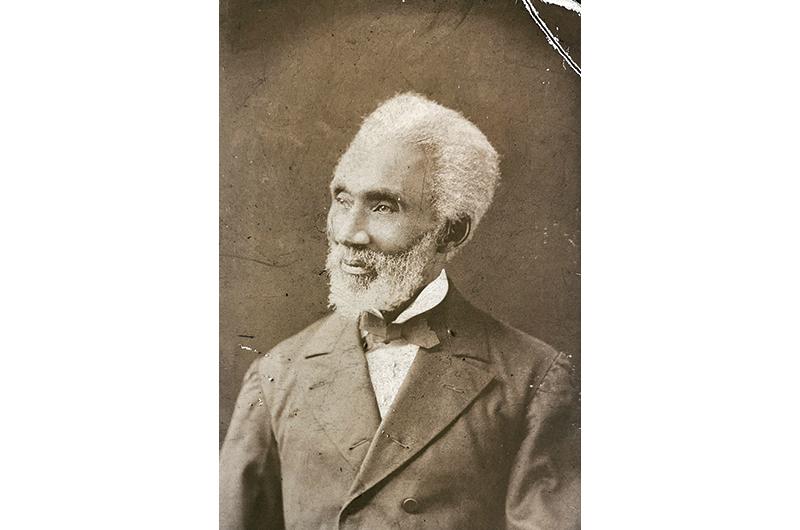

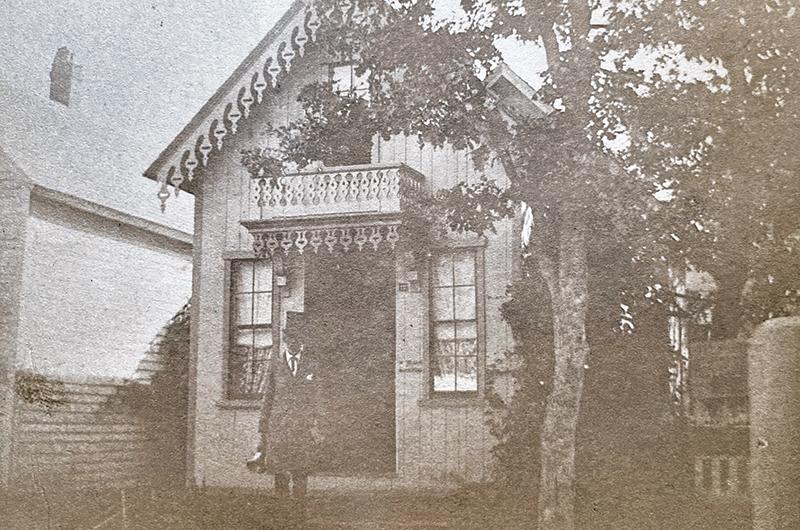

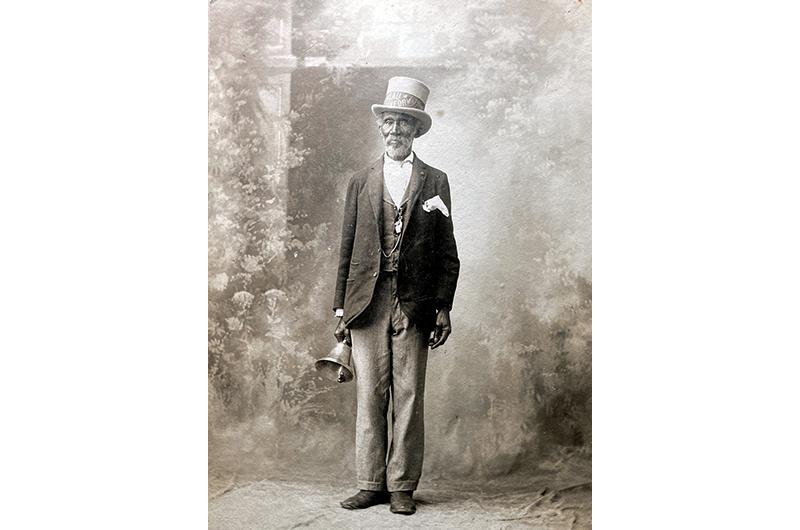

It was a skeleton whose existence that even I, an African American former Oak Bluffs town columnist for the Vineyard Gazette, had no reason to doubt. Until, that is, on a tip from a commenter on this magazine’s website, I began to look into the life of the Reverend William Jackson, Oak Bluffs town crier, who walked the streets of town in the late 1800s ringing a bell and calling out the news of the day. And who, it turns out, in 1871 bought a home that was built one year prior from William Brock at 12 Central Avenue. That’s an address in the heart of the supposedly “restricted” Camp Ground, and suggests that Jackson may have been among the first Black seasonal homeowners of Oak Bluffs’ historic African American community.

That fact alone is worthy of the man’s place in local history. But before getting too carried away in celebrating Jackson’s status as an early and notable African American of Martha’s Vineyard’s Oak Bluffs community, it’s worth noting that, like so many others over the decades, the Vineyard was where Jackson came to vacation and retire after a long life. A life that in his case was simply extraordinary, beginning with his birth as a free Black man in Norfolk, Virginia, in August of 1818, more than forty years before the Emancipation Proclamation. It was the same year that the abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass was born into slavery one state to the north, in Maryland.

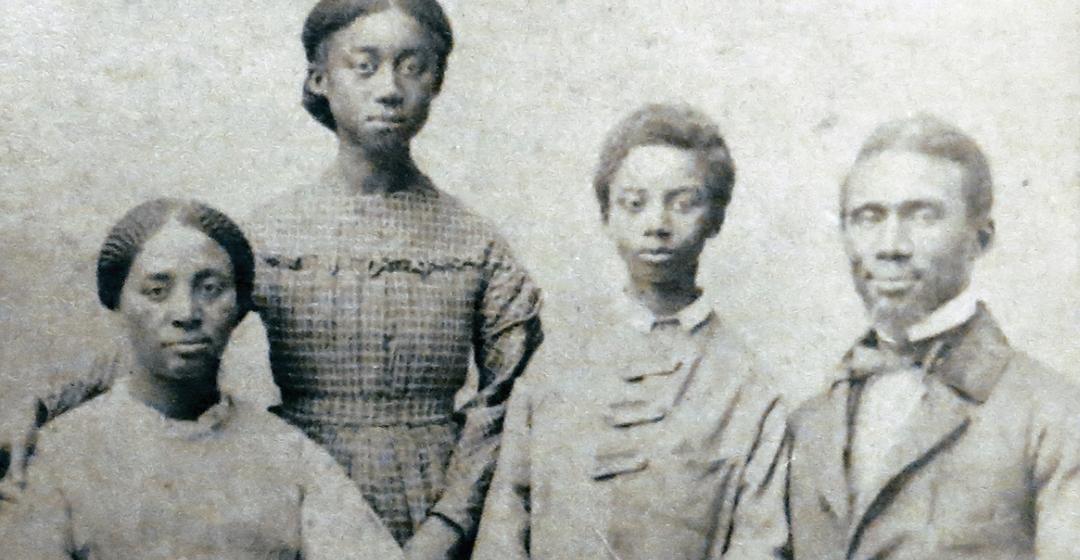

Much of what is known about Jackson is from his 173-year-old journal, which is today housed at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, coupled with studies by his late great-grandson Julian Youngblood and Valerie Louise Craigwell White, his great-great-granddaughter, who is writing a book about him. Jackson’s parents, Henry Jr. and Keziah Jackson, had been born into slavery, but at some point had been manumitted by their putative owner. Both Henry Jr. and Henry Jr.’s father, Henry Sr., Jackson’s grandfather, were seamen, pilots who owned their own boats. Henry Jr.’s boats had evaded British blockades during the War of 1812. And in 1824 he guided the Revolutionary War hero General Marquis de Lafayette on local waterways on the steamship Virginia.

Captain Henry Jackson Jr. moved his family to Philadelphia in 1831, essentially fleeing the white backlash after the Nat Turner slave rebellion, which took place not far from Norfolk. That rebellion, led by Turner, an enslaved Baptist preacher, had left some fifty white people dead. In the aftermath, hundreds of Black people were killed by both mobs and the state.

Jackson, who was about thirteen when the family moved to Philadelphia, also spent time on ships and eventually joined the Navy, which unlike the Army had welcomed sailors of color since the American Revolution. He served on the USS Vandalia, which in the 1830s mostly did duty off Florida and in the Caribbean, and on USS Grampus, where his journal tells of chasing pirates and slave ships in the Caribbean and of a two-day storm that almost destroyed the ship. In addition to a healthy respect for weather and the sea, Jackson’s time in the Navy left him with an aversion to alcohol, thanks to an incident in which sailors drank whisky from a barrel where a body was being preserved.

“From that day to this I can bear neither [the] taste or smell of whisky,” he wrote. “A good reason too.”

After leaving the Navy, Jackson returned to Philadelphia and became a butler – but not for long. On September 16, 1842, he was ordained a Baptist minister. His first church was Oak Street Baptist, now Monumental Baptist, in West Philadelphia. Oak Street remained his home church until 1854, though he took intermittent leaves to serve parishes in Newburgh, New York, and Wilmington, Delaware. He was especially proud that under his watch Oak Street Baptist became the first African American church in the nation to be allowed a bell – they were generally forbidden to Black churches lest they be rung to communicate the arrival of slave catchers.

It’s unknown whether Jackson ever rang his church bell in warning, but he was prepared to risk his life to help the enslaved escape. He may have inherited the passion for universal freedom from his father, who back in Norfolk had assisted at least one other enslaved person in buying his manumission. The stakes for runaways got much higher after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which allowed slave owners and their agents to cross into free states and, with the help of federal law enforcement, abduct almost any person of color they were inclined to accuse of being an escaped former slave. The law was anathema to abolitionists. Soon after its passage, United States marshals made their first arrest – and first mistake, taking a parishioner of Jackson’s church named William Henry Taylor.

“I felt morally and religiously bound to strike for his freedom and if possible to rescue a fellow man from the custody of this would be master,” Jackson later wrote in his journal. “The whole community had been thrown into the most terrible excitement over the arrest of [Taylor], the fugitive slave. Whereupon I felt myself nerved with moral and physical courage to do my duty, and save a brother man from perpetual and cruel bondage.”

With the help of “a band of brave men,” he managed to kidnap the prisoner from the United States marshal. They dressed him up as a woman, and within hours had spirited him away toward Canada. “As the leader of the rescuing party,” Jackson reported, “I was duly arrested and incarcerated in the city jail. Though it had been indicated by the officer at the time of my arrest that I should try to get bail, I surrendered myself up at once and made no effort in that direction,” he wrote. “For I regarded it as no disgrace to be arrested and imprisoned under this infamous and inhuman law, or for advising my fellow men ‘that if they would be free themselves they must first strike the blow.’”

Through the intercession of some of the leading clergy of Philadelphia and others, Jackson was soon out on a writ of habeas corpus. But just as his own parents had felt obliged to move north when Norfolk began to boil, Philadelphia became an untenable place for Jackson. New Bedford, Massachusetts, a major station on the Underground Railroad and a seat of abolitionism, was an obvious place to relocate. He became the pastor of the Second Baptist Church there in 1855 and, according to his journal, carried on where he left off. “I am revived and more lifted in my mind than I have been for some time past,” he wrote in his journal in 1857. “I have during the past week been very successful in helping two men to obtain their freedom, one from Washington [D.C.] and one from Kentucky.” He also mentions that around this time he began to visit Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket.

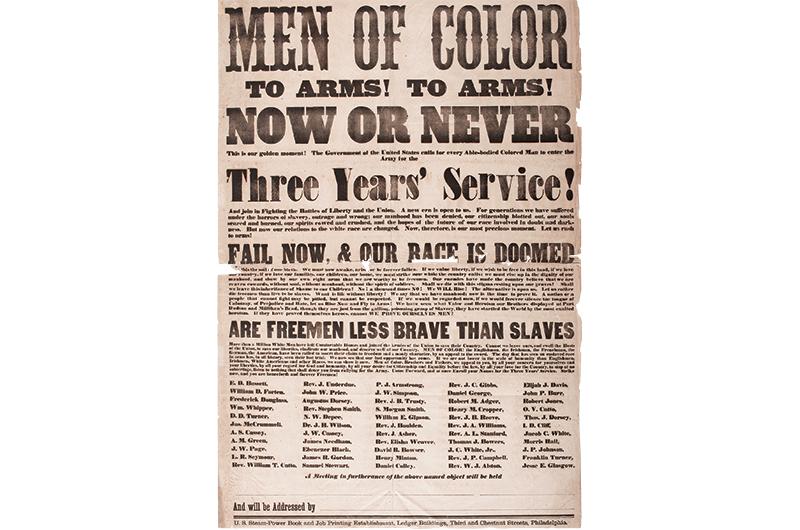

In New Bedford, Jackson was a part of a large and vibrant community of free Black people, many of whom worked in the whaling industry and some of whom had escaped slavery. The most famous among these was Frederick Douglass, who became a friend of Jackson’s and whom Jackson invited to visit Martha’s Vineyard. When Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation authorized the creation of Black units in the Union Army, Douglass was one of the principal recruiters for the famed 54th and 55th “colored” regiments of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Douglass’s own sons were among the first to join, and it was almost certainly the great orator who in July 1863 enlisted Jackson to serve as the 55th regiment’s chaplain, which led him to South Carolina to perform his duties. He was honorably discharged from the regiment in 1864 and returned to New Bedford and the Salem Baptist Church, which he had formed in 1859, to serve as pastor for another six years.

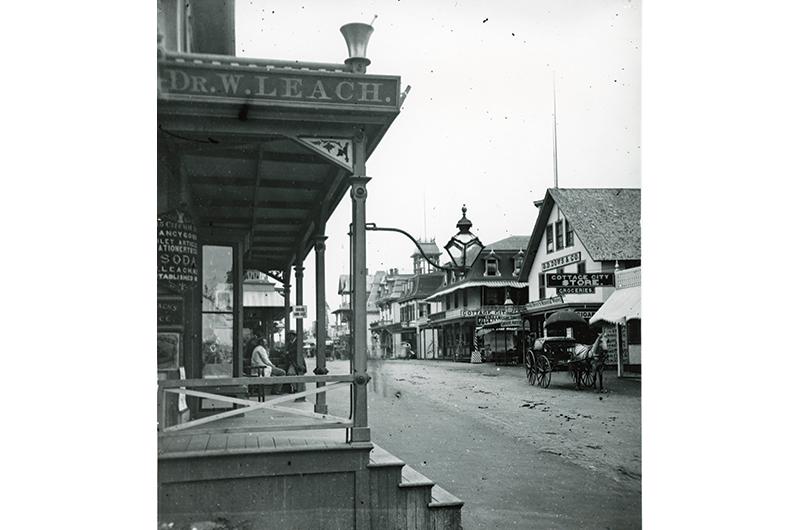

Around 1870, Jackson left the Salem Baptist Church and later served as pastor at Providence and Newark congregations. In 1871 he bought his home in the Camp Ground and began spending summers in Oak Bluffs, where he eventually took a part-time job as the town crier. There are no records of the town paying his salary, so it was likely a group of local businesses that engaged him to walk the streets and announce the news of the day in his best Baptist preacher’s voice. In pictures of him on the job from the time, he is invariably carrying a bell, which he no doubt rang to attract attention to his announcements. It may have been a bell that Jackson had been presented with years before in New Bedford to honor his work assisting people running from slavery. That bell had been made of brass from the original New Bedford Liberty Hall bell, which in the years after the Fugitive Slave Act had been rung to warn townspeople that there were slave hunters in town, and which had been destroyed in a fire in 1854. (The city honored Jackson again in 2018 on the occasion of the bicentennial of his birth.)

In the few photos from the time that we have, it seems he became a valued member of the Oak Bluffs and Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association communities. He also appears to have remained active in the cause of Civil Rights: in one image he is in a group with Amanda Berry Smith, who, born into slavery in 1837, was a Methodist evangelist, missionary to Africa, and founder of an orphanage for African American children. In July 1876 his most renowned friend, Frederick Douglass, was his house guest in Oak Bluffs. It was, the Providence Evening Press reported, a restful visit for great men. Douglass was persuaded to speak at the Tabernacle one afternoon, though sadly there is no record of what he said, only that according to the Evening Press, the musical selection “Joy to The World” began the program and Douglass spoke eloquently for forty-five minutes to an “enthusiastic greeting.”

After retiring from the ministry in 1884, Jackson continued to divide his time between the Vineyard and New Bedford until his death there on May 19, 1900. He is buried in the New Bedford Oak Grove Cemetery with four generations of his family. His bell, sadly, was lost to the family at some point during a move. His family kept the house in the Camp Ground until 1922, after which his memory seems to have faded to such a degree that it was replaced with the myth that African Americans weren’t welcome in the neighborhood.

Given that, it might be unwise to state categorically that in addition to all his other accomplishments the Reverend William Jackson desegregated the Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association. Much better to say he was one of the first of now many African Americans to own a home there (if not also in the town of Oak Bluffs). And he was quite definitely one of the first great Civil Rights heroes to be associated with the Island of Martha’s Vineyard.

12 comments

12 comments

Comments (12)