For Kahina Van Dyke, financial services executive and owner of the Narragansett House bed and breakfast in Oak Bluffs, purchasing a home on Martha’s Vineyard wasn’t only about summer vacations or investment strategies. It was about preserving a sense of legacy, both her own and that of the historic Island town she has come to know and love.

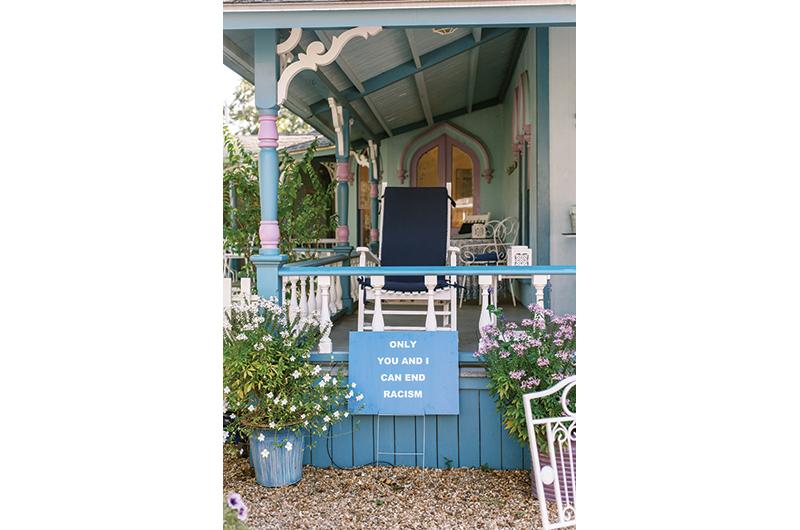

“Oak Bluffs was created from this multidenominational, multiracial, radical view that humanity rules,” Van Dyke told me when we met at the end of a strange summer, sitting six feet apart on the patio of her newly restored Victorian-inspired cottage. I was there ostensibly to hear about the renovation, and the impressive main house adjacent, purchased by Van Dyke a decade prior. But it quickly became apparent that Van Dyke, recently named one of the top twenty-five women leaders in financial technology, had more on her mind than remodeling. “The Methodists were here, doing what was right, regardless of what society said was the law at the time,” she continued. “Slavery was legal,

so what was the problem? They were like, ‘No. We think that this is wrong.’”

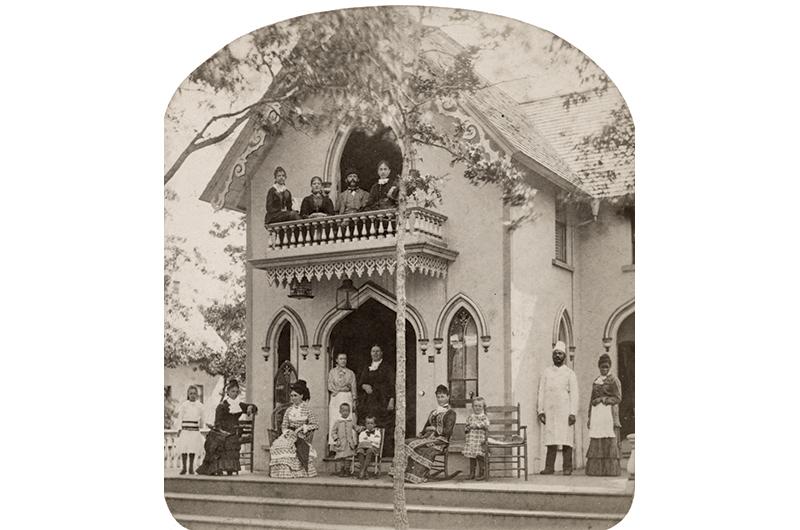

Though Van Dyke feels a strong sense of reverence for the Methodist-founded Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association and its physical and spiritual center, the Tabernacle, it’s the surrounding neighborhoods, including the one in which she now spends every summer, that she feels most called to preserve. The Copeland District, named for landscape architect and developer Robert Morris Copeland, was created in the mid-1860s, and has come to be known for large Victorian homes, picket fences, and a network of picturesque town parks. The Narragansett House, which Van Dyke and her husband, Claudio Casarotti, bought in 2018, was built by the Island carpentry firm Ripley, Hobart & Co. in 1870, around the same time as nearby Union Chapel. “I have a photo of the original innkeepers with their African American chef on the porch with the guests,” she remarked disbelievingly. “Oak Bluffs is not a normal place in America in 1875, just like it’s not a normal place in America in 2020.”

It’s this sense of community built on refuge and respect that first drew Van Dyke to purchase her own piece of Oak Bluffs history more than a decade ago. She chose an attractive nineteenth-century Victorian that sits less than a block from Inkwell Beach, the very beach where her father used to bring her to swim during summer visits as a child. And it explains why she chose to invest on the Island at all, despite a whirlwind career in global banking that took her from New York to London, Dubai, Madrid, and beyond, before Silicon Valley called and she and her young family settled on the West Coast. “This was the first house I bought,” she said. “This is my home. Everywhere else is transitional; you go there for a job, an opportunity, an experience. I will be coming here forever.”

Purchasing the Narragansett House and adding “innkeeper” to her résumé was, perhaps, a less obvious turn of events.

“My husband said, ‘We’re buying a hotel? You have a full-time job. What are you doing?’” But again, it was a deep sense of preservation and responsibility that led Van Dyke to take the plunge. “I didn’t want it to fall into the hands of someone who wasn’t going to continue to operate it as a guest house, as a place that could welcome people.”

Van Dyke comes from a long line of pioneers and preservationists; her family tree on both sides reads like an abridged lesson in American history. Descended on her mother’s side from actual Puritans – a seventh great-grandfather was one of the founders of Dedham, Massachusetts – and on her father’s side from freed enslaved people who established themselves in Dutch-settled Philadelphia, Van Dyke was taught from a young age that legacy is not something to be taken lightly.

“My mother’s ancestors came over on ships and founded the state of Massachusetts. And my father’s family came over in ships being kidnapped, later found a haven, and did everything they could do to invest in their community,” she said. “So on both sides of me were these two anchors of the founding of this country, the great American experiment. It makes me feel like I’m in a long line of people who fight to do the right thing.”

As a trailblazer in the financial tech industry, Van Dyke has been pioneering on a global scale, quickly working her way up the ranks at Citibank and ultimately launching internet banking in various European markets. “They wanted young, creative, curious people,” she said, modestly remembering her early years in New York City. “They didn’t know if the internet was going to be anything.”

A three-month assignment in London turned into fourteen years in six countries. Van Dyke credits her success working across so many markets and populations to an overall philosophy that looks for similarities among the differences. “I always say we are 90 percent the same and 10 percent different. In the end I was running product and development in twenty-seven countries, and it worked because we focused on what was the same. Everyone cares about their kids; everybody wants to feel safe.”

Van Dyke brings this same philosophy to her new role in hospitality, making sure guests feel at home during their time spent at the Narragansett House. She sees the inn as more than a place to stay, and has worked hard and fast to become a part of the Island creative and social communities, launching the Sundowner Porch Series (sunset cocktails on the porch with live music by Island musicians), as well as readings and art openings featuring local and visiting painters, writers, and photographers of color.

Innkeeper and preservationist seem natural callings for Van Dyke, but only because she is so authentically tuned in to what makes this particular corner of the globe worth both sharing and preserving. She recalled inviting Bobby Rogers, a young Black photographer, to the hotel in 2019 as part of a newly launched artist-in-residence program. It was his first time visiting the Island and she sent him to the Inkwell for inspiration. “He came back and said, ‘You’re never going to believe what happened. The police stopped traffic, let me cross, and told me to have a nice day,’” Van Dyke remembered with a laugh. “He was like, ‘What is this place you have brought me to?’”

Rogers was meant to return for a second residency this past summer, but Van Dyke reported that he was instead photographing police brutality protests in Minneapolis, Minnesota, an ironic turn but one that highlights the role the Island has played for Van Dyke and so many others in the current climate of pandemic-fueled anxiety and social unrest. As Van Dyke and her family planned to leave California for another Vineyard summer, like many they faced new challenges and uncertainties. But skipping the trip altogether was never on the table.

“I knew right away that if we could legally open, we would open,” she said definitively. “We couldn’t imagine not being here, especially during this time, with this community.” Despite a spring’s worth of cancellations at the hotel, Van Dyke felt a responsibility to be present at the inn, even if it meant they’d be the only ones there. “We didn’t know what it was going to be like,” she said. “But even if it was just us sitting on the porch waving at people, then that’s what it was going to be. For 150 years people have been on this porch every summer. It’s not falling down on our watch.”

On a personal level, returning to the Island during a time of such turmoil also felt right. “I will tell you, coming here in June, it was like we were traumatized and needed to heal,” she said. “And I knew this community would heal us. The Island is a healing place.”

To be sure, it was not the Vineyard summer they were used to. Her children, nine-year-old twins, were unable to attend camp at the ymca, typically a highlight of their year. Bookings at the inn were steady but slow. But there were upsides to the mandated slower pace. “It actually reminded me of the old Vineyard,” Van Dyke said, recalling summers of her youth. “There were no events, which I love.”

She also was pleased to learn that her neighbors, many of whom are multigenerational families who have lived in the Copeland District for decades, spent more time in their homes than usual. “This is the first time many of them have been here for more than two weeks,” Van Dyke said. “Normally they’re renting, and this year they were here all summer.”

A slower schedule allowed Van Dyke more time for another project she had already planned: the completed renovation of her guest house. After working with architect Chuck Sullivan, of Sullivan + Associates Architects in Oak Bluffs, to expand and update the family’s main residence, Van Dyke chose to bring him on again in order to maintain a sense of continuity, not just between her homes, but throughout the neighborhood.

“We wanted to make it feel like it’s always been here,” Van Dyke said of the smaller cottage. “It was important that it was like a miniature dollhouse of the Victorian.”

Matching porches, upstairs balconies, and an open-air dining area between the two houses serve to connect the spaces both functionally and aesthetically, while indoors a sense of openness and abundant light prevail. “Light and air are really important elements. You don’t need any lights on during the day; there are windows everywhere.” Van Dyke gestured to the compact yet uncluttered space around her. “People always ask about privacy, but I’m not here for privacy. I’m here to sit on the porch. It’s all about being out.”

Though she admits it takes her some time living in a space to get a feel for it, she imagines that as her children grow and have families of their own, they’ll spend more time in the main house while she and her husband camp out in the cottage. “This summer was wonderful. It was our little nest,” Van Dyke said of their first season in the space. “It was a good time for nesting.”

Between hunkering down with her family and maintaining some sense of normalcy and community at the inn – she was even able to host her beloved Sundowners on the porch – Van Dyke was able to find moments of peace and connection in the midst of a difficult summer. After touring her homes, we took a quick stroll of the neighborhood, walking the short blocks to the inn (normally, she rides back and forth on a vintage turquoise bike), where she pointed out the B&B’s ample outdoor seating area and wraparound porch.

“If you look at the news, it becomes overwhelmingly sad,” she said. “But then we’re all sitting here and feeling this connection. There is a strong connectivity. That community to me is why we’re here.”

Regardless of what the future brings, Van Dyke, who purchased a third property known as Dunmere-by-the-Sea this past fall, is committed to remaining established in the Copeland District, doing what she can to see that the legacy and intention of its founders are respected and maintained.

“I’ve lived all over the world, and there is no other place like this,” she said as we walked back toward the beach. On the corner she stopped to wave to some neighbors sitting out on their own porch, three generations of women who had been visiting their family home for more than half a century. “For those of us who understand on a deep level what this place means, it’s why we fight so hard to protect and preserve it.”

2 comments

2 comments

Comments (2)