When Matt Chamberlain – the all-smiles, all-star center fielder and spiritual center of the 2018 Martha’s Vineyard Sharks – stepped up to the plate on an ominous August afternoon three years ago, everything hung in the balance for the boys of the summer. The Island’s college summer league baseball team had split the first two games of the best-of-three league championship against the Worcester Bravehearts, and the two teams were now in the Shark Tank, as the regional high school’s baseball field is colloquially known, facing off in the rubber match.

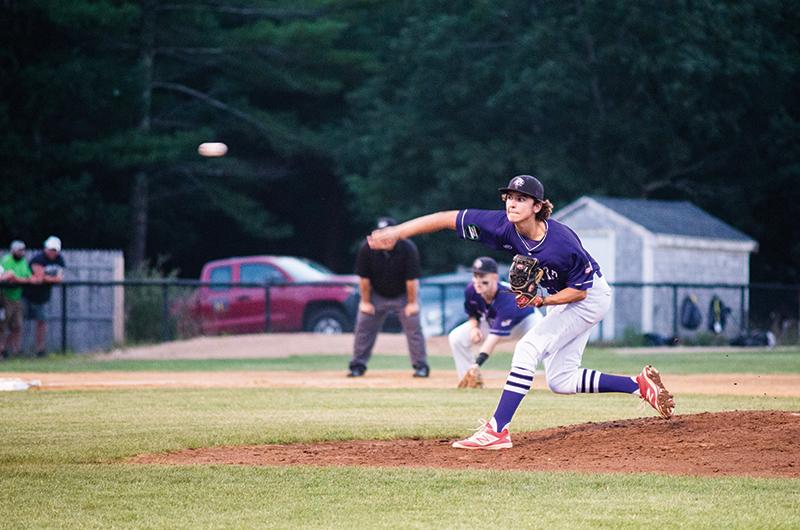

On the mound for the Sharks was Chance Huff, a six-foot, four-inch Florida-grown flamethrower whose low-nineties fastball made even the actor Bill Murray (a team co-investor) do a double take. Huff had just been named the Futures Collegiate Baseball League’s best pitching prospect and was prepared to start his college season at Vanderbilt University in a couple days. But so far on that fateful day, as chance would have it, Chance Huff hadn’t had it. After four high fastballs, a walk, and two hits, the Bravehearts were up 1–0.

If things didn’t look great on the field by the time Chamberlain came to the plate, they looked much worse off it. A purple sky matched the Sharks’ jerseys, and sideways rain pelted players and a horde of fans. The series had already lost two games to washouts, and Sharks players – who had scheduled ferry reservations months in advance in order to make it to college campuses in time for their fall semesters – were forced to cancel them.

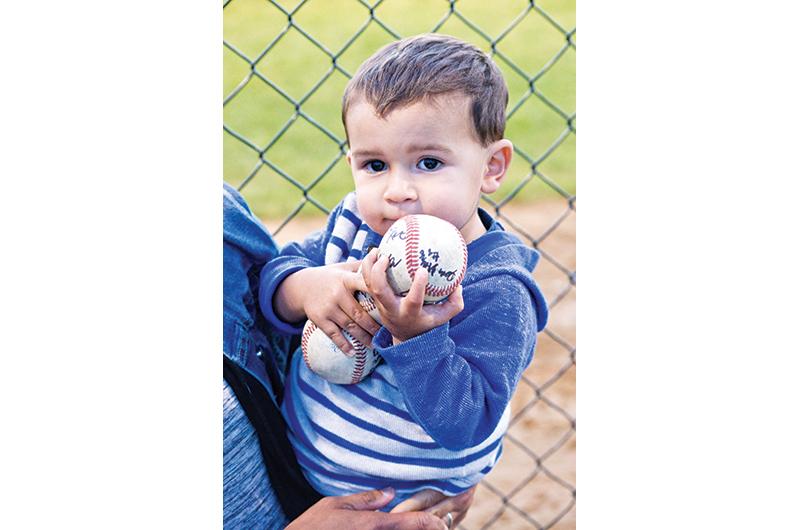

But there was too much on the line not to play the game: too many rough midnight rides on the Patriot charter vessels, too many tweenage host siblings whose entire summers came down to chasing foul balls and idolizing their new big brothers. The Sharks couldn’t call it quits yet. They hadn’t even gotten to bat.

So the team – quite literally, the players – rolled up their sleeves, rolled out the tarps, readied the rakes, and started tossing drying agent. No puddle went untended, no base unwashed. Fans, who had religiously followed the team for two months as it ran to the top of the Futures League’s standings, put on their ponchos. Vineyard Vines had them covered – and sponsored.

And Chamberlain, who had spent all summer robbing and stealing home runs, bases, and hearts with his flowing, shoulder-length hair, had one more chivalrous act of quickness and guile he needed to complete. With a storm still lurking, he started off the bottom half of the first inning, digging in his cleats on the left side of home plate, his knees bent, bat on his shoulder, and hands clenched. By the time he worked a 3–1 count on the Bravehearts pitcher, so were everyone else’s hands – a hard-fought championship mere inches from slipping out of their grip.

Then lightning struck. Twice.

Let’s pause there. The Martha’s Vineyard Sharks – a college summer league baseball team located on a summer resort Island – were no strangers to acts of god prior to that Chamberlain at bat in 2018. In fact, acts of god, or, more appropriately, small acts of miracles from mostly year-rounders, are why the team still exists and is about to celebrate its tenth anniversary.

Founded in 2011 by a group of investors who wanted to bring college summer league baseball to the Island, the Sharks’ origins actually stretch back further, when a like-minded fellowship of the Island baseball community, including former high school baseball coach Gary Simmons, architect Phil Regan, and builder Doug Hoehn, dreamed up an idea to renovate the high school field.

“This team actually started long before the Sharks arrived,” current co-investor John “JR” Roberts recalled.

“A group of guys got together and wanted to build a new field at the high school. There was a piece of land behind the school that was basically being used as a junkyard. They made a proposal to the school to take the land and build a sort of field of dreams.”

After the field of dreams came to fruition for the high school team, carved out of Vineyard scrub oak rather than Iowa cornfield, the group took a more metaphorical page out of Kevin Costner’s playbook, inviting teams from the historic Cape Cod Baseball League – the best college summer league in the country – to the Island to play a few games every summer. With a long tradition that dates back to the late nineteenth century, the nonprofit league serves as the traditional pre–minor league feeding ground for the county’s top college players, as future MLB MVPs ship up to live with host families and spend a summer developing their skills on the best ballfields (and beaches) in the country.

By the late twentieth century, as the country’s college and professional baseball industrial complex expanded, an alphabet soup of generally for-profit lesser leagues started to proliferate in other seasonal summer destinations across the country, from the Minnesota northwoods to the Alaskan frontier. For owners, they were half business venture, half baseball nostalgia – a far cry from owning the New York Yankees but not a bad way to make a buck in the Hamptons if your last name wasn’t Steinbrenner.

For the Vineyard baseball community, that begged an obvious question: why not here? A different group of investors decided to make it happen, pouring in money and becoming charter members of the for-profit, four-team Futures League. The first Martha’s Vineyard Sharks game was played ten years ago this June, and the team won its first Futures League title in 2013, graduating players such as Dylan Tice and Islander Tad Gold who would go on to get drafted.

“It was highly successful,” Roberts said. “But the costs of operating the team and building out the field were enormous. And everything was paid for without taxpayer dollars.”

By the 2014 and 2015 seasons, the team was struggling financially. While other Futures League organizations had thousand-seat stadiums that would often fill throughout the grueling, nearly fifty-game season, the retrofitted Shark Tank rarely saw fan numbers top triple digits. Sponsorships were hard to come by, and buses and ferries to games as far away as New Hampshire could cost as much as $50,000 per year. Equipment, housing for coaches, stipends for host families, food, and salaries for the general manager and his assistants pushed the team budget even higher – present-day estimates put those figures at around $250,000.

And that didn’t include the costs of building out the stadium. At the start of the 2013 championship season, ownership invested more than $350,000 to install lights and a grandstand with seats from Baltimore’s Camden Yards. Later improvements included a brick façade.

Meanwhile, debts to vendors went unpaid. Investors, who had made no money in the first five years, backed out. Finances were mismanaged. The dream was in danger of dying.

“I don’t think any of the initial investors truly understood or financially planned for what was going to have to happen,” Roberts said. “They made a bunch of mistakes along the way that put them in a really big hole, and that group of investors faded away. They said, ‘We’re not going to put in anymore.’ That was the low point.”

That’s when Roberts, who is a partner in the food distribution business Island Food Products (IFP), stepped in. An early volunteer for the team and longtime baseball fan who helped whenever he could by boiling hot dogs and handing out tickets, Roberts had seen firsthand the value of the organization to the Vineyard community.

“I really felt that this was something great for the Island,” he said. “I saw Camp Jabberwocky coming to the game and being as happy as can be. I saw kids learning to be announcers, playing catch with their host families. By that point, it wasn’t just a baseball field. The baseball field had extended into the community.”

He wasn’t alone. A third group of investors, mostly year-round Islanders, banded together to save the team. These included Roberts’s IFP partners Alan and Adam Bresnick and Peter Marks as well as Scott Lively and Charles Hajjar. They examined the finances, ultimately deciding to pump hundreds of thousands more dollars into the organization so it didn’t fold. They started by making sure all debts to Island vendors, ranging from electricians to clothing manufacturers, were leveled, and then looked for ways to change the team’s organizational structure so that it could survive moving forward.

“It was touch and go for a while,” said Roberts. “But guys really stepped up to the plate financially in order to save something that we didn’t want to see disappear...and we got through that crisis.”

Instead of focusing on a model funded by ticket sales, the new group of investors looked to increase sponsorships and involve more Island businesses. After the 2018 season, they joined the nonprofit New England Collegiate Baseball League (NECBL), generally considered the second-best college baseball league in the country behind the Cape League. Nonprofit status gave the team more freedom to solicit donations and start a philanthropic foundation for scholarships, both avenues the investor group hopes to pursue more actively moving forward. They still make no money, and the return on investment is zero. But, according to Roberts, the finances are stable.

The finances weren’t what it was about anyway. Roberts said he knew the Sharks were worth it when a kid with autism had asked to sing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” during the seventh inning stretch. After the song, his father sent the team a letter saying it changed his entire outlook on life. Roberts said it made him cry.

“To look back and know we almost lost something that adds so much value to the community,” he said, “I can say we made the right decision by stepping in. And we preserved something that can last forever.”

The most important shift for the Sharks had nothing to do with money. In 2016, they hired Russ Curran as their general manager. It’s been his team ever since.

The former leader of Ted Williams Little League in Worcester and owner of an Amateur Athletic Union team called the Shamrocks, Curran was a career baseball guy by the time his son, Mac, headed to the Vineyard for the summer to pitch for the Sharks in 2015. It was there that he met Roberts, whose own son, Jack, was playing second base for the Sharks. They were just two dads yukking it up in the grandstand while their kids battled to bring home a championship on the field. A few years later, one of them happened to be a leading investor in the team. The other happened to have some good ideas about how to save it.

Curran started working on developing sponsorships, putting signs in the outfield in an effort to fund the team’s sizable operations budget. By 2016, Curran – an affable, true blue Massachusetts guy with the work ethic of a pack mule – wasn’t only working on sponsorships. He was recruiting most of the team through his substantial connections in the baseball world. It made sense to formalize the partnership.

“I guess they said, ‘Just make Russ the GM, because he’s doing everything anyway,’” Curran recalled.

As the Sharks’ only full-time employee, Curran is responsible not only for recruiting the team but for parenting them as well, figuring out housing for the forty-plus college players that come every year, and making sure they are well fed and well behaved (the former generally much more challenging than the latter). He’s part Theo Epstein, part Terry Francona, part that South Boston guy singing “Sweet Caroline” in the Fenway stands, a man deeply educated in the game of baseball on the field with a tough-love, straight-talking papa bear attitude off of it. That part isn’t too important, though; he’s on the field 365 days a year.

“One of the biggest moves we ever made – one of the best moves we ever made – was finding Russ,” Roberts said. “I’ve never met someone who loves baseball like Russ. His dedication to the team is unparalleled. He loves the players. He has their backs. He also has an overall sense for the community, and he’s really just a guy who can do it all. He’s the heartbeat of the team.”

Recruitment begins the day the season ends, according to Curran. Because the Sharks are in a top league but not the Cape League, this involves concocting a perfectly balanced cocktail of players from top-twenty-five power-conference D1 schools across the country, regional D2 and D3 programs, and the occasional Vineyard kid. In the Futures League, Curran was generally only able to snag power-conference players if they were incoming freshmen. But the NECBL gives the team more leverage with D1 schools, and with a shortstop from Florida State and a second baseman from Wichita State, the 2019 team had a middle infield that could play together in Fenway one day.

Curran also likes having between five to seven return players who know the Island and the team. But for all the players, there’s only one immutable requirement. “I choose character guys,” he said. “I do Google searches on all my players to make sure there’s no skeletons in the closet. I look at their social media, make sure it’s not anything that wouldn’t look good toward the team. I think it’s important to get good-character kids who want to be here and want to be involved. They have to be able to play, but they also have to be able to read to third graders at the school.”

It’s not a perfect science. “Sometimes players sit by themselves for the first host family dinner, and then a week later they are chanting, giving away tickets at Harborfest [in Oak Bluffs], and end up being the best teammate anybody could ask for,” Curran said. “And then, every once in a while, you have a guy come in who thinks his shit don’t stink, and he doesn’t fit in at all.”

As far as the baseball is concerned, his philosophy is simple. For pitchers, it’s about throwing strikes. For hitters, it’s about not missing them. “We’ve had a formula for a long time,” he said. “If they’re a pitcher, no walks or hit batsmen. If he throws a bunch of balls, he’s not gonna fix himself in summer ball. For hitters, I look at on-base percentage, not a lot of strikeouts. And I like a vacuum cleaner in the field.” In other words, character may be most important, but winning is pretty crucial too.

With powerhouse schools such as Vanderbilt University or Louisiana State University, he lets the coaches know the positions he’s hoping to fill. “You don’t even have to tell me their names,” he tells them. “If you have three guys, send them to me when the time comes. I do pick and choose after that.” Smaller schools require a bit more attention as the quality of players, while still very high, can be variable. Coaches in his network might send five to seven names, which he winnows down with the help of the Sharks’ three coaches: head coach Jay Mendez, hitting coach Billy Uberti, and pitching coach Mac Curran (Russ’s son).

At the same time that he is scouting players from colleges, he is also recruiting families to house them. Not surprisingly, the latter is much harder than the former. Whereas mainland teams have the advantage of cheap rent and ample housing stock, the Vineyard is, for a lack of a better term, a different ball game.

“It’s luck. I can advertise 1,000 times for host families and never get a call,” Curran said. “But it always somehow figures itself out.”

Most of the team’s investors stuff about five players each in their attics. But the most prolific host families are otherwise unconnected Islanders who form a boisterous contingent in the grandstand during home games, cheering on their respective housemates. They include military veteran and semi-professional heckler Tom Rancich, known for his behind-the-plate aphorisms. His advice to players on swing discretion? “Find one you like. But be careful. Before you know it, you’ll be married to her.” Of hosting players he told the Vineyard Gazette, “They’re fabulous,” before adding, “but they’re teenagers. They don’t know how to take out a stinking trash can.”

The Chatinover family has hosted nearly six players per year ever since their son, Keith, now a Middlebury College student and a Dukes County commissioner, was in middle school. He grew up with Sharks in the house every summer, and by 2013, along with his father Jonathan, had started announcing the team’s games from the broadcast booth. The Sashin family hosted Sharks until their own son became one: James Sashin, a six-foot, five-inch pitcher who went to the University of San Diego, described the experience of playing with the team he had idolized for his entire childhood as “surreal.”

But the most prolific Sharks host of all time is probably Dianne Powers. Though never a parent nor a player, the former West Tisbury selectman, school committee stalwart, register of deeds, and avid sports fan started hosting Sharks in 2012. She’s had nearly five (and one year, seven) players in her house every summer since, sharing space with her four great Danes.

“The home vibrated for two months,” said Powers, who is still in touch with many of the players. “But it was special, every summer. I remember walking in my door and seeing the pile of shoes. And I knew, it’s summertime.”

Fast forward to the ominous August night at the Shark Tank in 2018. Remember? Matt Chamberlain is at bat. Series is tied. Hands are clenched. Lightning. The whole deal.

The team, the first one entirely put together by Curran, had been a dream team all season, winning its first game in a blowout and never looking back. The players from D1 programs, second baseman Tate Kolwyck and pitcher Chance Huff from Vanderbilt University, were stars on the field – a surprise to no one. But it was the D2 and D3 players, including catcher Nick Raposo, shortstop Kellen Hathaway, and, of course, Chamberlain, that carried the squad, whether it was at the ballpark or on the beach.

“We just surrounded everybody with talent,” Curran recalled. “And picked kids who wanted to be here. Some managers won’t even look at D2 and D3 kids. But we had two last year who were signed to pro baseball.”

The team had steamrolled through the playoffs. But the fate of the season now rested on Chamberlain’s shoulders, its weight far heavier than the three pounds of maple he was gripping. Not only was a championship on the line, but the moment seemed to hold in the balance the years of tireless effort from Roberts, Curran, and the many others that had gotten the team to August of 2018.

They had no business funding a program where the return on investment came in the form of cheeseburger grins from thirteen-year-olds who got to run the bases between innings. They had no business recruiting or housing top-level D1 talent, made possible mostly by the generosity of Islanders who had little more to give than a spare bed. They had no business being there. Yet there they were. And Chamberlain wasn’t going to let them lose.

The first lighting strike came from his bat, a crack loud enough to send a ball to the heavens, send fans to their feet, and, most importantly, tie the game. The second strike, almost moments later as the inning came to a close, was more literal, a crack in the sky loud enough to pause the game, open the heavens, and send fans scrambling into the state forest.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. But it also couldn’t have been better. After an hour-and-a-half rain delay, with the game tied 1–1, the Sharks were crowned champions. Co-champions, but champions nonetheless.

Chamberlain and Curran embraced in a bear hug on the field after the game. “You’re the best,” Curran told him and asked, most importantly, if he’d be back in 2019. Chamberlain added a nod to his smile. The following year Chamberlain, Raposo, and others held true to their word, returning to the team and leading it to a championship appearance in its first year in its new, more competitive league. The future of the team looked as bright as it had ever been headed toward its tenth year in the Shark Tank.

Then the 2020 season was cancelled due to the pandemic. Not just for the Sharks and the summer leagues, but for the entire Island and the off-Island world. But like truth, baseball will out; Curran and Roberts never stopped recruiting, certain that the game would return this summer. The incoming 2021 team already has about ten guys from top-twenty-five schools, including Maryland, Vanderbilt, Louisville, and Virginia Tech. The team is stable financially, and every year Curran comes closer to his goal of having ticket fares covered by sponsorships. Currently, all kids are free.

But the Sharks’ biggest problem for 2021, as it always is, is off the field. Powers, priced out by the real estate market and ready to downsize, moved back to her hometown in Pennsylvania. That’s at least five players who are going to be looking for new homes this summer. The loss nearly moved Curran to tears. It’s going to take another small act of the baseball gods to find them beds. Good thing the Sharks are used to those.

“I’m coming back for opening night,” Powers said. “There’s no question about that. I wouldn’t miss it for anything.”