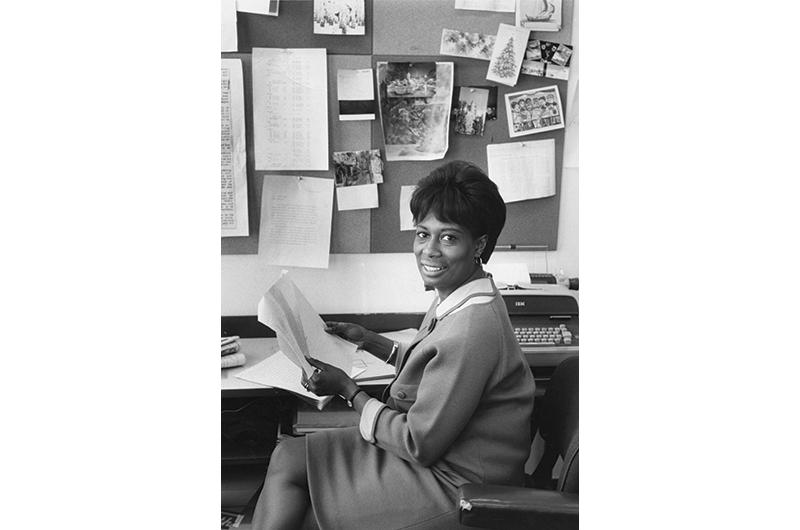

The barriers to professional advancement for women and people of color were even higher than they are today. Nonetheless, inspired by her parents and the great Civil Rights leaders of her generation, Dolores Allen Littles, one of this year’s judges in our annual photo contest, rose to the top of the photography publishing world in New York. Now eighty-eight, she’s still got her eye on the bright future.

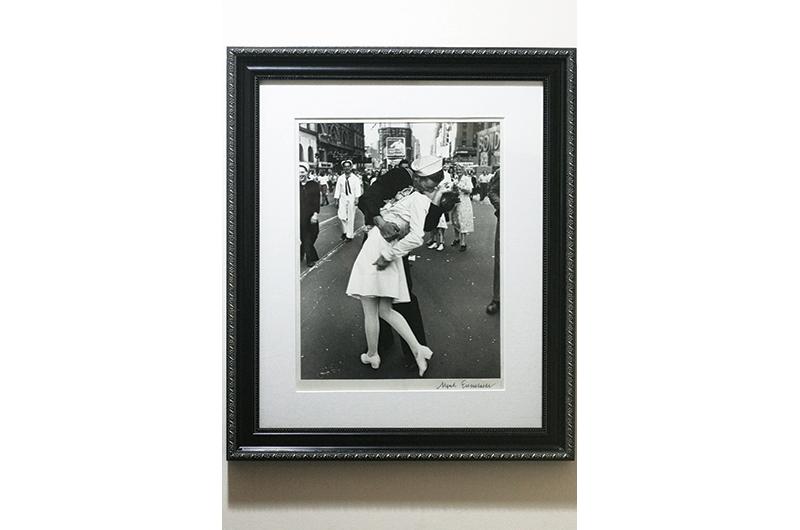

“Aw, Eisie gave me that,” says Dolores Allen Littles of Oak Bluffs, pointing to a frame on her dining room wall. I turn to look, expecting perhaps to see a great-nephew’s drawing. Instead, I am face to face with Alfred Eisenstaedt’s iconic V-J Day photograph of a sailor kissing a nurse.

“Do you want one of those?” she remembers Eisenstaedt asking her. “I said, ‘Sure.’ He said, ‘Enjoy.’”

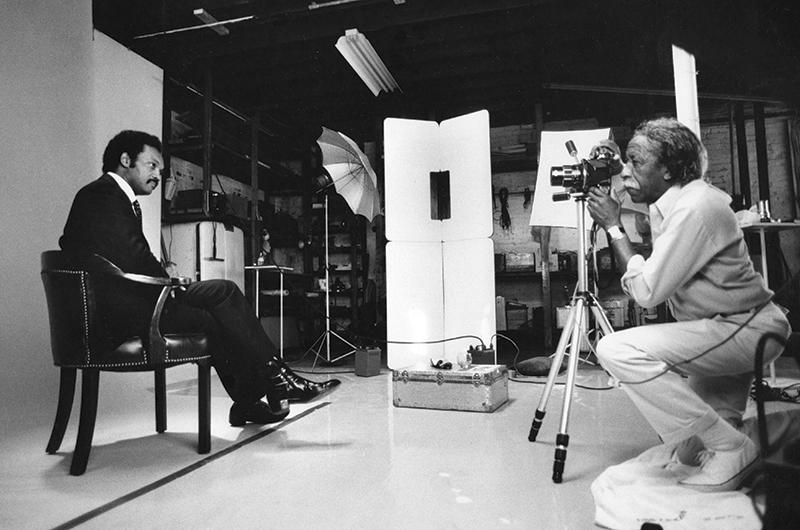

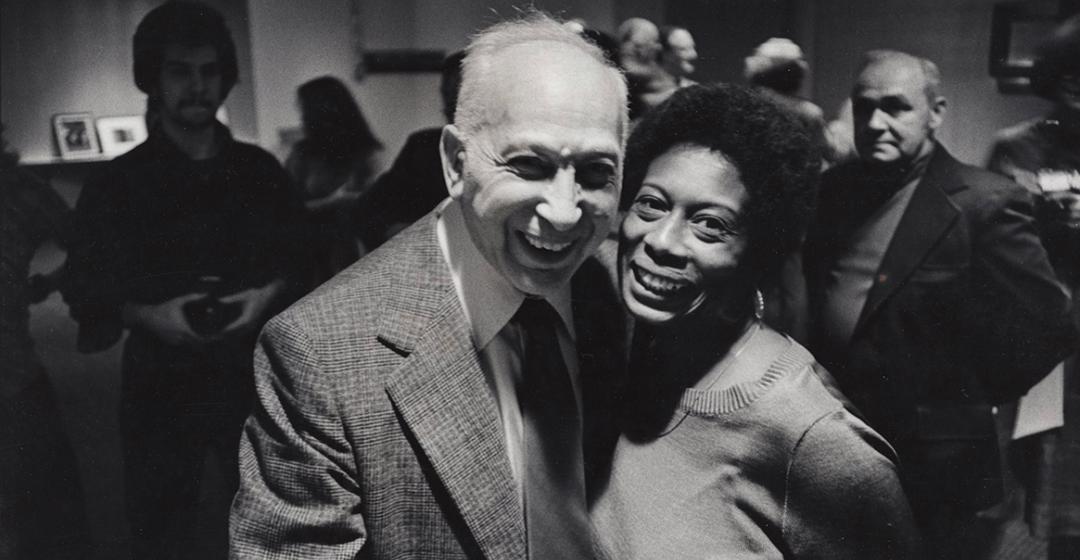

As the former director of photography for Time-Life Books, part of Time Inc., in its heyday, Littles collaborated with Eisenstaedt for years. “He never let me down,” she says. And he was not alone. Her blue-brown eyes shine and the smiles come nonstop as she recounts her memories of working with numerous photography giants of the twentieth century, including Jay Maisel and Dmitri Kessel. She talks about the great artists of the day as if they were old schoolmates. “You know Gordon Parks?” she asks, and when I shake my head she says, “You should. He’s probably the most notable African American photographer of all time.”

Her humble, joyful attitude has clearly been a part of her success, helping her, an African American child on Long Island during the 1930s, grow up to become the director of photography for one of the top publishing companies of the day. But humility and friendliness can go only so far to explain her unusual rise in an era when, even more than now, a person’s race and class in America either smoothed a path to success or made it exponentially steeper. As a powerful woman of color who lived through the heyday of the Civil Rights movement of the mid-twentieth century, she was inspired by the “Big Six” civil rights heroes – Martin Luther King Jr., James Farmer, John Lewis, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, and Whitney Young – who helped organize the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. She and her husband of fifty-five years, Jim Littles, who died in 2010, were even lucky enough to meet most of them in person on more than one occasion.

She gets teary when remembering people who have helped her on her way, relaying times she personally thanked Thurgood Marshall and John Lewis for their impact on her life. She recalled nearly swooning when greeting Dr. King and Randolph from her old porch on Narragansett Avenue in Oak Bluffs.

“I have marched in my share of protests and strike lines,” she remembers of the sixties. “But can you believe I had climbed so high that when it came to the March on Washington, I organized buses sending hundreds of protesters, but I couldn’t be there? When you sit at the big desk, that’s how you make an impact.”

But as great an influence as those Civil Rights icons were, when Littles looks back she says her initial spark for equal rights and a wider life came much earlier, from her mother.

“Once, I was promised pay for completing chores for a white woman,” she recalls. “I had been saving up for Capezio shoes.” But at the end of the day, she was given only an old skirt instead of the promised cash. Her mother marched her over to the woman’s house and explained very clearly that her daughter deserved proper compensation.

“That taught me to think of myself as worthy,” Littles remembers.

From very early on Maude Allen was determined to expose her daughter Dolores, her only child, to the world. In 1941, when Littles was only nine years old, her mother encouraged her to travel to North Carolina to see relatives. “Mom had faith in me that I’d be fine. Plus, the Traveler’s Aid Society kept an eye on me.” It was there that she first saw Jim Crow laws on display and had to use bathrooms marked “Colored.”

“Mostly, I viewed the signs with curiosity,” she recalls.

Back in New York, she and her mother would see movies at the famed Apollo Theater in Harlem – one of the very few screens showing programs with Black people. “It was really the Apollo that inspired me,” Littles says today. “I found it so exciting: the live music, movies, performances.” It was where she felt safe and possibilities felt endless. On Wednesdays, the pair met at their local movie theater in Hempstead, New York, for half-priced matinees often starring Judy Garland, with Littles always stopping first at Woolworth’s for fresh cookies. At a time when a handful of Black women were becoming entrepreneurs, the young Littles also visited her great-aunt Lenore, a hairdresser who lived in Harlem. “Auntie Lenore” was something of a socialite and brought her to the acclaimed Savoy Ballroom and Radio City Music Hall, introducing her to a glamorous scene and further broadening her horizons.

Every day, after a full day of ironing clothes for a living, her mother prepared family dinner and dessert. Her father, William Allen, who also pressed for a local cleaner, was sure to be home by five o’clock. In the evenings Littles devoured the news too, especially The Huntley-Brinkley Report. “The show was a real light for me. It excited me because they were talking about the world.”

When Chet Huntley talked about “Big Sky,” Littles thought, “I’d like to go out to the Rocky Mountains and see what that’s like.” But she never did go because she heard locals were not accepting of Black people. “I have been all over the world,” she says, “but I’ve never been there. I hear it still may not be welcoming.”

“Turn that off,” she remembers her mother saying of the television. “Go do your homework.” Which was fine because she loved school, especially art and English classes. Although her teachers were white, her schools were integrated. “I looked up to my grammar school English teacher, Mr. Pill. He always made me feel like I could do anything.”

Hempstead High is where someone else caught her eye: her future husband, Jim, who went on to become a successful artist and pioneer in photo retouching. Though he, too, eventually had an office on Madison Avenue, where he regularly helped produce covers of Vogue magazine and occasionally did projects for Time Inc., their work was separate from one another.

When she turned eighteen in 1950, her parents let her take her first unchaperoned trip far from Hempstead. She had seen Martha’s Vineyard listed in the back of Ebony magazine as a safe vacation spot for Black vacationers, complete with a cartoon of a ship on a wave, and said to a girlfriend, “Let’s try this.”

She fell for the Island right away. “From the first day I was here, I knew this was a place for me...years later when I needed to get away from the magazine, this would be my escape.”

After that first trip, Littles began to follow her heart. “Living in New York always felt like my destiny, and I had to be true to that.” Her parents struggled financially, but together the three found a way to support her enrollment first at Pace College in New York City, where she completed her associate’s degree in secretarial coursework, and later at the City College of New York, where she earned her bachelor’s degree in education.

She didn’t want to be a teacher, however. “I always wanted to work for Time-Life,” she recalls. “Photography tells a story. I always wanted to learn the story – what is really going on?” After a first job at the Voice of America broadcasting organization, where she adored learning about other countries and languages, she got a position as a typist at the clip desk at Life magazine. Although the company was almost entirely white, she quickly climbed the ladder. Within months she was working closely with the editorial and copywriting departments.

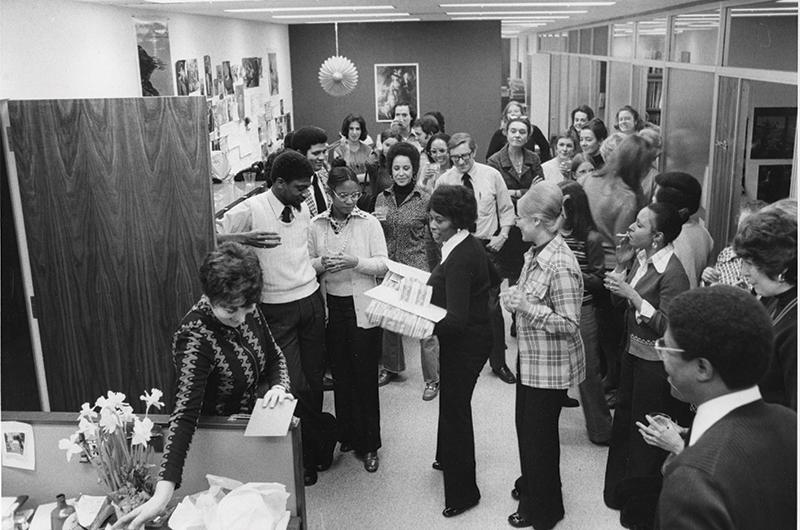

On Friday evenings, over a catered meal and cocktails, the magazine staff worked to close the stories. Littles sat among colleagues, methodically checking captions, spelling, and punctuation and typing edits until two or three in the morning. “They’d send me home in a nice car on late nights. It was a pleasant atmosphere with a lot of laughter,” she recalls. On Saturdays there was even more work to be done when the magazine galleys arrived from Chicago.

She went on to become a member of the photography editorial staff for numerous Time-Life Books on topics ranging from foreign countries to food and specialties. The best part of her career? “It was all so interesting in one way or another. Each project was a learning process.”

Coincidentally some of Littles’s most important mentors at the company also escaped to the Vineyard in the summer. She had been coming on her own as often as she could afford to when she spotted a managing editor while boarding the ferry. “Then I began to understand – they [publication executives] are all here now!” she laughs today.

In particular the late Maitland “Mait” Edey, the former editor in chief of Time-Life Books and a Vineyard Haven resident, and the late Ralph Graves, the former editor of Life magazine and a Chilmark resident, encouraged her rise at the company. “They were always behind me 100 percent and more,” she says. Back when she was a young typist, she enlarged a copy of Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” and posted it on the walls of her office. Jay Gold [managing editor of Time] said to her, “You gotta be kidding me! That’s wonderful!”

Another time, when affirmative action and other efforts to recruit persons of color to corporate jobs were just beginning, a friend who was a member of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) encouraged her to write a paper about African Americans adapting to corporate America and vice versa. When she was invited to present the paper before the APA conference in San Francisco to over 1,000 people, Edey assured her, “Whatever you need, Time Inc. will pay for.”

In the early 1980s, she retired as director of photography for Time-Life Books but continued to do extensive freelance work. During her twenty-eight years with the company, Littles had close encounters with major American figures such as

John F. Kennedy, John Lewis, Meryl Streep, Christie Brinkley, John Glenn, chef Jeremiah Tower, and Henry Luce, among many others. “There was always something going on that’s incredible. It’s like, can you top this?” Littles remembers of her work.

In the end, she says, it no longer felt like a job.

“I remember going down the hall one day having completed a deal and saying, “I can’t believe someone is paying me to do this….It’s a great joy knowing you are doing what you should be doing. And to be recognized for it.”

These days her comfortable Oak Bluffs home feels like a celebration of her experiences. A framed certificate rests on a handsome wooden side table. It’s inscribed by the Library of Congress recognizing Littles’s contributions to the 2018 HistoryMakers program, the largest African American video oral history archive in the United States. Nearby is a 2017 Townsend Harris Medal for outstanding postgraduate achievement at City College of New York, as well as a certificate recognizing her contributions as a former board member of the National Urban League of Northern Virginia, to name just a few.

Personal treasures also abound, including a collection of baskets left behind by her late husband, Jim, who learned traditional African basket making from a ninety-six-year-old descendant of plantation slaves. They are extraordinarily beautiful objects; in the mid-1990s he gave workshops on basket weaving techniques at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Other than her occasional reach for a Kleenex when emotion demands it, Littles appears confident and comfortable in her white T-shirt and shorts, stud earrings, polished fingernails, and red square ring. She is in her element, sitting amidst her curated curiosities including china teacups, orchids, wooden African masks, and tidy stacks of reading materials while talking about what matters most: “Kindness, equality.”

The home, which features a wraparound porch and lovely gardens, was built by her and her husband in 2000, after many decades of sharing a house in Oak Bluffs with three other people. There, after fifty years as summer residents, they fulfilled their dream to retire to the Island part-time while keeping a residence in their hometown of Hempstead, New York. Three years ago Littles stopped splitting time between Oak Bluffs and Hempstead and embraced life as a full-time Islander.

Now eighty-eight, Littles continues her lifelong mission of furthering justice and equality, serving on the local NAACP scholarship committee and encouraging people to continue the struggle. Lately, she’s been working on a memoir.

“I heard [John Lewis’s] message again while watching his funeral – ‘When you see something, say something, do something....’ – I’ve tried to do that. Speak up when I witness anything from ageism to sexism.”

Talking about the current Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, which gives her hope, her thoughts go to her neighbor, Danielle Hopkins, a young adult who is now a leading local BLM advocate.

“Next time I see her, I am going to tell her – to witness her doing what she’s doing, this is the reason I have worked so hard in my life, to see this happen.

“We are all the same,” she says, and then says it again for emphasis. “We are all the same. We have to really learn to respect one another. ’Cause it’s come back to bite you one way or the other.”

8 comments

8 comments

Comments (8)