Four hundred years ago the paramount sachem of the Wampanoag nation made friends with the newly arrived Pilgrims at Plymouth. According to the award-winning author of the recent book This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving, Massasoit’s allies on the Cape and Islands were not exactly thrilled with the plan.

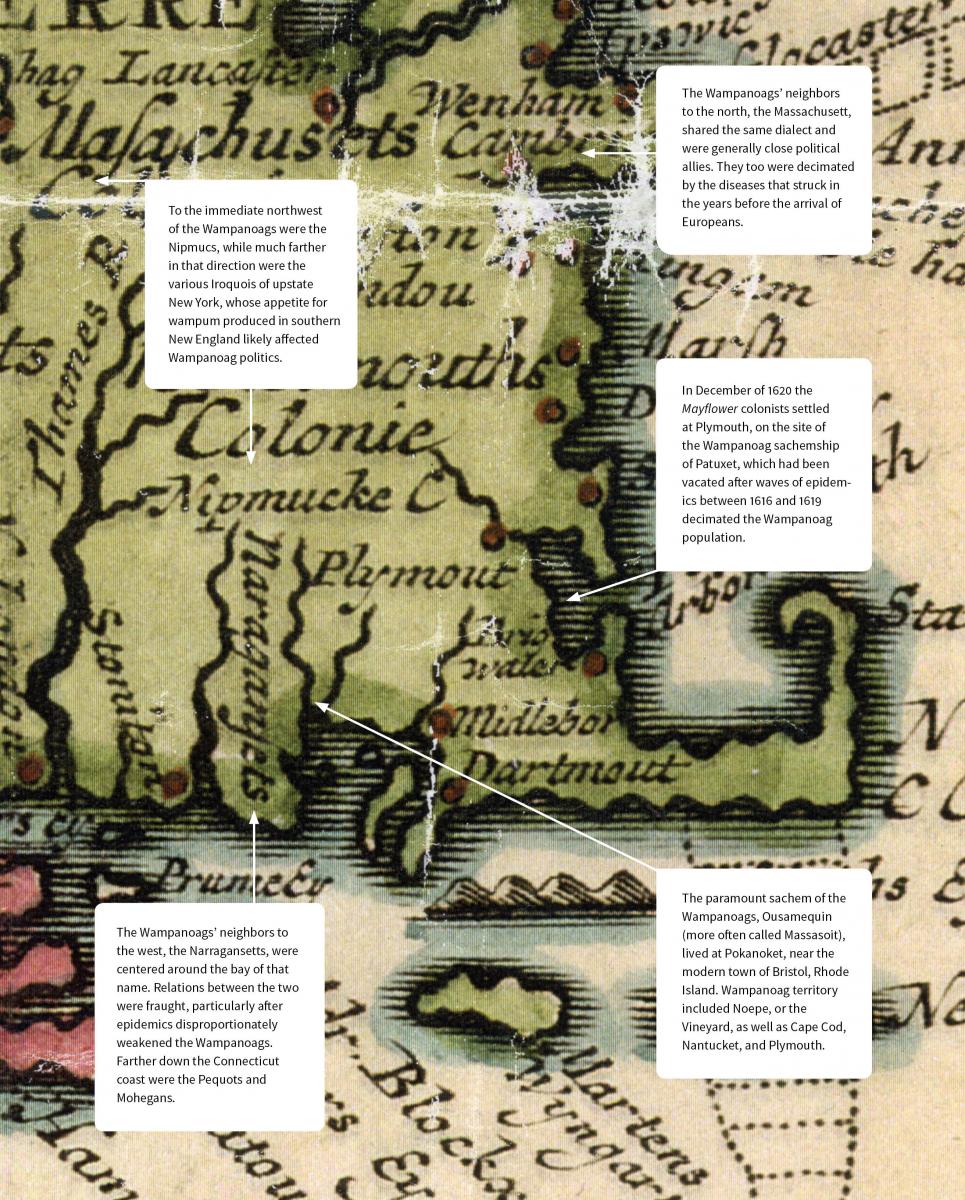

The “first Thanksgiving” took place at Plymouth, of course, near the foot of Cape Cod. But to the limited extent that the traditional Thanksgiving story treats the Wampanoags seriously, it focuses more on the communities west of the Cape and Islands, in the Taunton River Valley. Doubtlessly this is because the Wampanoags’ paramount sachem, or great leader, Ousamequin (more often called Massasoit) lived at Pokanoket, where the Taunton empties into Mount Hope and Narragansett Bays, at the site of the modern towns of Warren and Bristol, Rhode Island. It was Ousamequin and his men who made up the ninety or so Wampanoags who feasted with the Pilgrims during that storied three days in November of 1621. Yet the Vineyard Wampanoags’ relationship to Ousamequin and his core followers along the Taunton was one of the most critical and yet underappreciated elements of both the Wampanoag-Pilgrim encounter and the catastrophic King Philip’s War a half century later. It’s impossible to grasp the events that followed that first Thanksgiving, in other words, without some understanding of the state of Wampanoag politics in the decades surrounding

the permanent arrival of Europeans.

As was true all over the Americas, power struggles within and between Native communities, as well as years of intermittent contact with the crews of passing European sailing vessels, helped shape Indian responses to the arrival of colonists who intended to settle permanently. In addition, long-term historical developments predating the arrival of the Mayflower influenced Wampanoag decisions in and after 1620. That history includes the rise of corn-beans-squash horticulture, the emergence of regional tribes, and decades of violent Wampanoag encounters with Europeans. So while the Thanksgiving myth would have us believe that Indigenous people were frozen in some kind of prehistoric stasis until colonization launched them into the modern era, it was in fact the colonists who entered a historical hot zone that would have lasting implications for both their own fate and that of the Wampanoags.

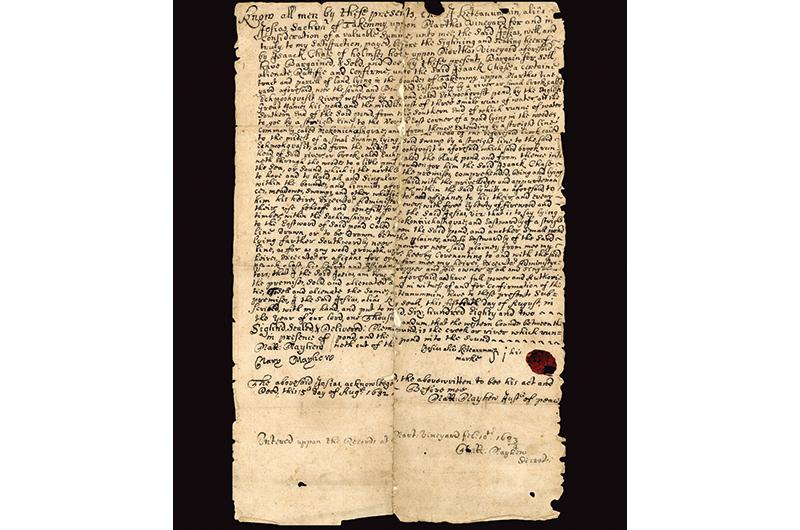

Recovering this past is enormously challenging given that colonists who were prejudicial and often hostile to Native people produced most of the records on which historians rely, but in the Wampanoag case that obstacle is not insurmountable. Colonial missionaries and traders interacted with Wampanoag people regularly, learned their languages, and considered some of them as friends. Their writings occasionally offer remarkable insights about Wampanoag society. Land deeds are also useful because sometimes the English tried to legitimize their purchases by including Indian testimony about the Native grantor’s historic ties to the land. Additional documentation comes from numerous Wampanoag protests to colonial authorities, court cases involving Native people, and surveys of Indian communities by missionary organizations. Archaeological site reports shed light on how people used the land, inequalities within Native society, trade networks, and religious practices. Indeed, it might not be going too far to say that there is more historical evidence about the Wampanoags than there is about the colonial poor.

Yet these materials still have serious limitations. Wampanoag men tended to represent their communities to outsiders, so the English rarely noticed the critical, behind-the-scenes roles of Wampanoag women and marriage alliances in politics. In the case of Ousamequin, we do not even know the name of his wife or wives, his mother, or his sisters and their husbands. Likewise, we have precious little information about spiritual considerations in Wampanoag decision making. Wampanoags generally did not discuss that subject with the English, and the English were wary of it in the first place given their belief that Native rites invoked the devil. Historians must always remain aware of these serious problems without being paralyzed by them. To do otherwise is to make history a story about the victors, which itself is necessarily incomplete.

No change in the more than 12,000 years of New England Indian life is more important for understanding Indigenous polities in 1620 than the rise of corn-beans-squash horticulture. Maize and beans developed in Mexico some 6,000 years ago, then spread up the Rio Grande, Mississippi, and Ohio Rivers before making its last stop in the Northeast. This expansion was a stunning feat of human engineering in which cultivators – certainly women, given their responsibility for the crops – bred ever larger cobs of corn and selected seeds that could grow in ever colder, wetter environments. Whereas some archaeologists once doubted whether New England Indians had adopted corn and beans as late as the 1500s or even early 1600s, there is now clear evidence of maize cultivation dating as far back as 700 years. The recent archaeological excavation of a Narragansett village from 1300 to 1500 CE containing scores of maize kernels as well as corn hills and underground storage pits confirms that southern New England Indians were growing maize, beans, and squash for centuries before their contact with Europeans.

These crops strengthened the people’s already rich nutrition and territoriality. Though Native people in southern New England were hunter-gatherers when corn, beans, and squash arrived, they were not nomadic. Rather, they migrated seasonally within their people’s clearly defined bounds. They spent the warmer months near coastal estuaries to exploit fresh- and saltwater fish, shellfish, sea mammals, amphibians, wild fruits, and marsh grasses. When the fall chill arrived, the people moved to sheltered uplands to hunt deer, bear, and other terrestrial animals for their meat, skins, and raw materials. The emergence of corn, beans, and squash made this rich life even more plentiful.

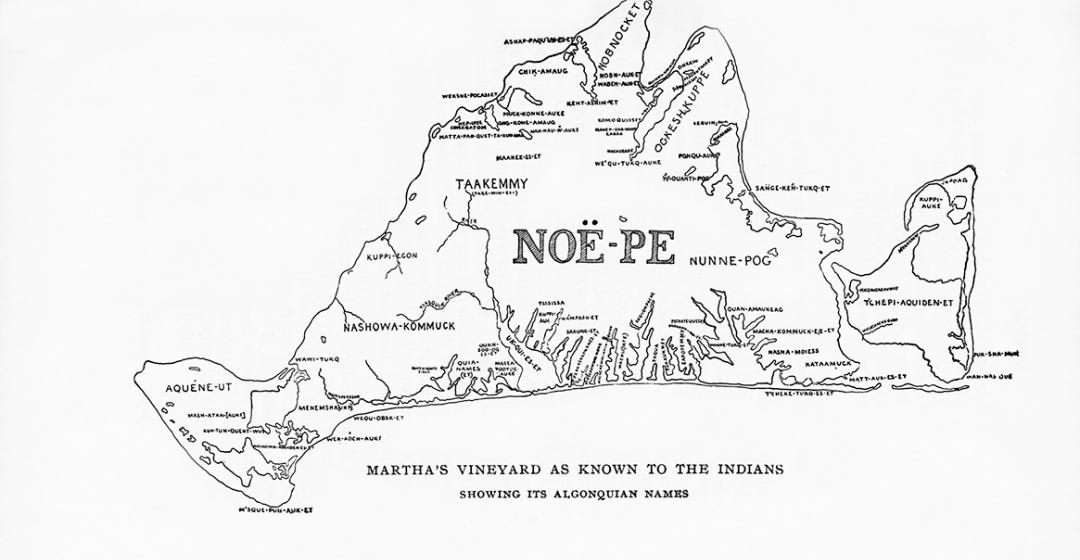

The result was one of the densest regional populations in Native North America on the eve of colonization. The best estimates range between 126,000 and 144,000 people for southern New England as a whole and 21,000 to 24,000 for the Wampanoags. The Vineyard alone, which the Wampanoags called Noepe (“dry land amid waters”), might have held as many as 3,000 people before seventeenth-century epidemics reduced that number by about half. As horticultural populations grew and competed for planting lands, their communities confederated into ever larger groups, later known as tribes or paramount sachemships.

These divisions corresponded roughly to linguistic differences, though shared language might have been as much a result of political affiliation as a cause of it. All Indians in southern New England spoke one or another dialect of the broader Algonquian language family. These dialects were mutually intelligible, so when previously distinct people allied, it tended to standardize their speech. That process was ongoing among the Wampanoags in the mid-seventeenth century, with the Vineyarders pronouncing some words differently from mainlanders. The Wampanoags and Massachusett people to the north shared the same dialect and, perhaps not coincidentally, were close political allies.

The needs of this growing horticultural population increased the list of duties for Native leaders. Each locality was represented by a sachem, usually a man but sometimes a woman (referred to as a sunksquaw, meaning “titled woman”) who had inherited the position from a father, paternal uncle, mother, or paternal aunt. Yet if the people judged the first in line to be inadequate, they could bypass that person for another candidate, just as they could replace an underperforming sachem. Once seated, the sachem handled relations with neighboring communities in consultation with a council of male representatives from elite families. When disputes arose, or when someone committed a crime, the sachem mediated a resolution or meted out punishment. With the rise of horticulture, the sachem also assumed the responsibility to allot planting grounds.

In exchange for this and other services, the sachem received the grantee’s pledges of love and loyalty and annual tribute in the forms of horticultural produce, furs and deerskins, labor, and portions of game. The sachem did not hoard this wealth or immediately redistribute it, though he or she was expected to sponsor certain ritual occasions and assist the poor and needy. Rather, the purpose of tribute was to fund the sachem’s political activities. For these reasons and more, southern New England Indians called their communities sachemonk, or sachemships.

Sachemships came in a variety of sizes. Some were no larger than a village and contained only a few extended kin groups. When the first English colonizers arrived on the Vineyard with Thomas Mayhew in the 1640s, such places included Sengekontacket, Nobnocket (West Chop), Kophiggon (Cape Higgon), and Squibnocket. Sachemship could also refer to a larger area about the size of an English town comprised of several of the lower-level sachemships, as in the cases of Chappaquiddick, Nunnepog (Edgartown), Takemmy (Tisbury), and Aquinnah on the Vineyard.

Far better known are regional polities that the English called nations or tribes, but which anthropologists refer to as paramount sachemships. Regionally, they included the Wampanoag paramount sachemship, to which the Vineyard belonged, as did the Nausets on the lower Cape. Just north of the Wampanoag, centered around Boston, was the Massachusett paramount sachemship. West of the Wampanoag, down the Rhode Island and Connecticut coast, were the Narragansett, Pequot, and Mohegan. These entities were each led by a great sachem who collected tribute from outlying communities in exchange for leading them in foreign affairs and war and arbitrating intercommunity disputes.

When the Mayflower arrived, the Wampanoag paramount sachem was Ousamequin, or Massasoit, leader of the community of Pokanoket at the mouth of the Taunton River in between the modern cities of Fall River and Providence. Precisely how he gained authority over the Vineyard is uncertain. According to colonist Matthew Mayhew, sometime in the distant past the Islanders appealed to “the greater Princes on the Main” to help them settle their internecine differences, for which they sent “presents annually...to oblige them [the mainland sachems] to give their Assistance as occasion required.” One sees such a relationship at work in a case from the 1660s, in which Nantucket Wampanoags appealed to the Pokanoket sachem to help settle a local murder. Yet Mayhew’s understanding of how the Islands fit into the greater Wampanoag polity was probably incomplete.

A paramount sachem’s relations with neighboring sachems and the people of his own local community tended to be consensual because they were kinfolk. Tribute payers from farther off were another matter. There is no surviving evidence that sachems from Wampanoag communities on Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, or Nantucket were related to Ousamequin, his sons, or any other sachems along the Taunton River. A lack of blood ties might explain why Ousamequin and his Pokanoket sachemship needed occasional displays of power to keep these places within the fold. Colonist Roger Williams, who knew the Wampanoags and Narragansetts well and spoke their languages, wrote that a great sachem periodically toured his outer dominions “with a guard of near two hundred.” Along the way, he held councils, parceled out justice, and had a special military elite known as pnieseosok (“counselor-warriors”) collect his tribute. Clearly some people were unwilling to pay it voluntarily.

Ousamequin and other Pokanoket sachems might have demanded tribute from the Island Wampanoags less for refereeing their internal disputes and more for managing a war against the Narragansetts from the west side of Narragansett Bay. Ousamequin told Williams that his people had been at odds with the Narragansetts since at least the period of his father’s rule, which is to say well before the arrival of English colonists. He did not say what this contest was about, but probably it was part of a chain reaction caused by demands made by the fearsome Mohawks for wampum beads. The Mohawks and their Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois League, confederates in upstate New York (Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas) had no local supply of the quahaug and periwinkle shell from which wampum was made, but required the beads for rituals that kept the fragile peace between their peoples. To stave off the Mohawks’ plundering raids, the Narragansetts traded and gifted them the beads, which, in turn, the Narragansetts extorted from other coastal communities.

The long-simmering war between the Narragansetts and Wampanoags might have centered on competition for such tributaries, or on the Narragansetts trying to subdue the Wampanoags themselves. Either way, Ousamequin’s collection of tribute from Cape and Island sachemships would have enabled him to conduct the diplomacy and raise the warriors to wage this war.

Ousamequin’s decision to ally with the European newcomers at Plymouth was directly related to his troubles with the Narragansetts. But it severely strained his relationship with the Cape and Island sachemships, at least partially because of developments that predated the colony. Since at least 1602, European sailing vessels had made annual visits to the New England coast, especially the Cape and Islands, almost always with violent results. Sometimes it was a matter of trigger-happy explorers overreacting to perceived Indian threats. At other times, the sailors took Native people captive either for training as interpreters and guides or slavery.

Dozens of Wampanoags lost their lives and freedom to such violence. In the worst of several cases, in 1614, English captain Thomas Hunt seized twenty-seven Wampanoags from two different locations whom he sold into bondage in Málaga, Spain. Remarkably, at least two kidnapped Wampanoags managed to return back home after absences of years to tell of their ordeals. One of them, Tisquantum or Squanto, a victim of Hunt’s, went on to play a key role in Ousamequin’s diplomacy with Plymouth. Another lesser-known figure, Epenow of Martha’s Vineyard, had been captured in 1611 by Captain Edward Harlow and reappeared on the Island after three long years of captivity in London. Understandably, many Wampanoags on the Cape and Islands judged Ousamequin mad for even considering an alliance with anyone from the English nation of slavers and raiders.

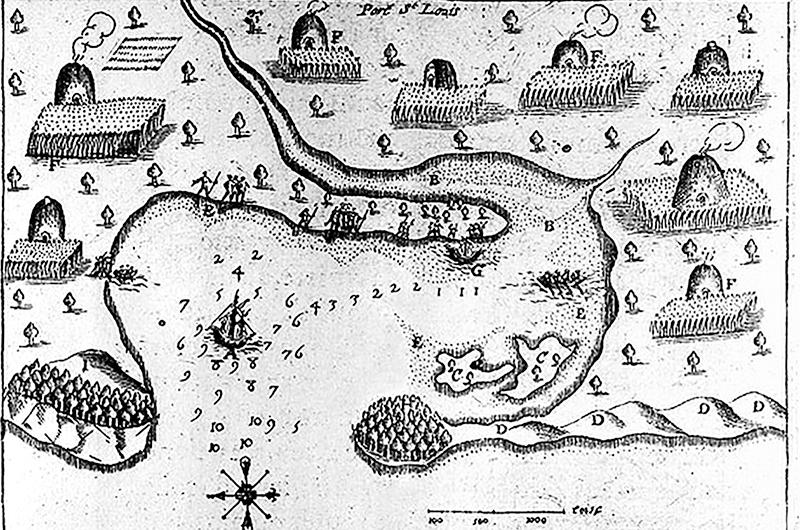

Credit: Atlas Historique, 1677, Martha's Vineyard Museum

Ousamequin took this gamble only because a vicious foreign epidemic swept away untold numbers of his people between 1616 and 1619 and left them in a far weaker position relative to the Narragansetts. The identity of this disease is unknown, but the results were unquestionably catastrophic. It knifed southward from Maine’s Saco River before halting at the Wampanoag-Narragansett border, reducing some villages by as much as 90 percent and traumatizing the survivors. Recovery would have been a momentous challenge even under the best of circumstances, but the Narragansetts made things worse by exploiting the Wampanoags’ new relative weakness to drive their westernmost settlements from the head of Narragansett Bay (around modern Providence, Rhode Island) to its east bank and reduce them to tributaries. As Ousamequin told Williams, “he was not subdued by war, which himself and his father maintained against the Narragansetts; but God, he said, subdued us by a plague, which swept away my people and forced me to yield.”

Under these dire circumstances, Ousamequin saw the English of Plymouth – and, more specifically, their guns and other metal weapons – as a means to beat back the Narragansetts. Furthermore, if he gained control over the flow of English trade goods, it would help him to regroup the shattered Wampanoags under his authority. He understood that this was a grave risk, but to him the earlier English record of violence spoke to the value of employing them against the Narragansetts.

Many Wampanoags disagreed, almost to the point of civil war. In 1621 and again in 1623, Wampanoag and Massachusett Indians threatened to break with Ousamequin in favor of aligning with the Narragansetts and dispatching the English. In the first instance, none other than Epenow was among Ousamequin’s leading opponents. All we know about the second insurgency, from Ousamequin’s own mouth, is that it involved an axis of sachemships from Cape Cod, the Islands, and Massachusetts Bay. The English sprang to Ousamequin’s defense both times, including a bloody strike against the Massachusett sachems in spring 1623 that Ousamequin appears to have intended as a warning against Wampanoags chafing under his leadership. The Cape and Island sachemships got the message and stood down, but their future actions seem to testify that they deeply resented Ousamequin’s use of English violence to project his authority.

It was probably no coincidence, for instance, that the Cape and Island Wampanoags began hosting Christian missionaries in the 1640s and ’50s, which they then used to sever their tributary relationship to the Pokanoket sachems. As to why their desire to break free of Pokanoket overrode their earlier aversion to the English, the answer probably lies in how the balance of power in southern New England had shifted since the 1620s. First, during the 1630s, upwards of fifteen to twenty thousand English migrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, based in Boston, making it more powerful than any neighboring tribe. Then in the Pequot War of 1636–37, colonial forces killed or enslaved hundreds of Pequots, most of them noncombatants. This ruthless display, combined with several fresh outbreaks of epidemic disease, which the Wampanoags widely attributed to the English or their God, led some Indians to think that it would be safer to ally with the newcomers than continue to oppose them.

The Cape and Island Wampanoags could have turned to Ousamequin to broker peaceful relations with the English, but that would have exposed them to exploitation that they would not brook. For one, Ousamequin expected his tributaries to pay him wampum, which was burdensome enough, never mind that producing beads for him invited plundering attacks from the Narragansetts. Instead, Cape and Island Wampanoags refused to engage in large-scale wampum manufacturing and used an alliance with the English through the mission to protect themselves from Pokanoket’s retribution. Strikingly, there is no archaeological or documentary evidence of wampum making on the Cape and Islands despite these areas having ready access to the shells. That does not mean that Islanders did not make wampum at all – they almost certainly did for their own ritual and decorative purposes – just that they did not do so on a scale to meet the demands of chiefly tribute collectors and colonial markets. It appears that they did not want the political trouble.

The Islanders also chafed under the Pokanoket sachems’ attempts to sell their lands. Notably, it was only after Ousamequin starting selling land from under the feet of his distant tributaries that Cape and Island Wampanoags began granting territory to the English and hosting English missionaries. Ousamequin’s son Wamsutta, who became paramount sachem in 1661 following his father’s death, was even more aggressive in this respect, including a sale of Nashaquitsa on the Vineyard in 1662. Better for Cape and Island Wampanoags to sell their land directly to the English and reap the material and political rewards.

At least in theory. The Vineyard’s colonial proprietor, Thomas Mayhew Sr., characterized Ousamequin “a great enemy to our Reformation on the island,” because, like most paramount sachems, he believed the mission would cut into his tribute. According to Mayhew’s grandson, Matthew, around 1650 the Vineyard received a visit from “an Indian Prince, who ruled a large part of the Main-land” backed by eighty armed men. Undoubtedly this was Ousamequin. Mayhew did not record what the sachem wanted, but probably it was to express his opposition to the mission. Later colonial accounts mention Ousamequin pressuring the sachem Nohtouassuet of Aquinnah to hold firm against Christianity and issuing death threats against Nohtouassuet’s Christian son, Mittark. Yet Ousamequin did not lash out violently at the Cape and Island Wampanoags, probably to avert blowback from Plymouth and Boston.

King Philip’s War of 1675–76 was the final break between the Cape and Island Wampanoags and Pokanoket. In it, mainland Wampanoags led by Ousamequin’s son, Pumetacom or Philip, rose up against English expansion, soon to be joined by most of the Nipmucs, Narragansetts, and Abenakis. Cape and Island Wampanoags tried to stay neutral, but that proved impossible. Eventually, under duress, they supported the colonies.

This wrenching decision enabled the Wampanoags of the Cape and Islands to survive the war intact and then assist mainland Wampanoag survivors to adjust to colonial domination. It seems in some ways a full circle from the anti-English position of the Island Wampanoags a half-century before, but it should not be lost that this critical chapter in both their history and the history of King Philip’s War was less a break from the past than an extension of historical developments that stretched back to the very beginning of the colonial period. They reached all the way back to a split in the larger Wampanoag nation over the mainland supreme sachem Ousamequin’s decision to attend that first Thanksgiving and ally with the English from the moment they arrived in Plymouth four hundred years ago.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)