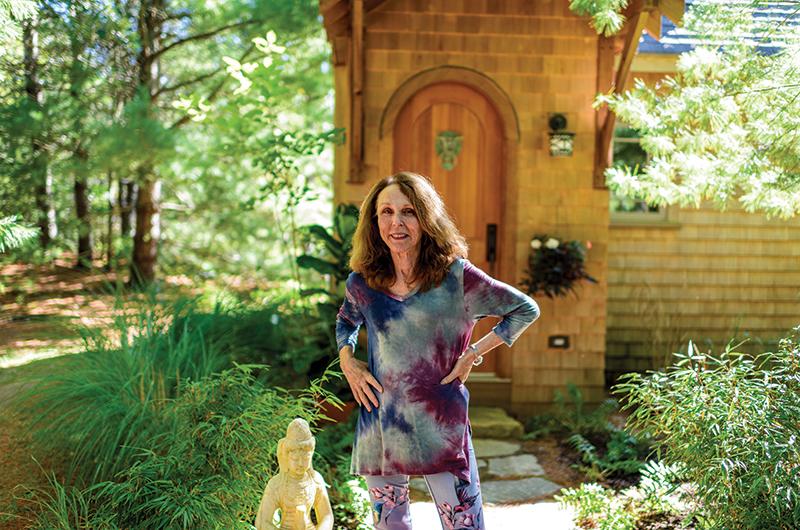

Houses, like people, can take time to grow into themselves. Ask Virginia Yans, whose West Tisbury guest cottage began as a single 256-square-foot room with a sleeping loft. Over time that arts and crafts–style post-and-beam mini house has evolved into a nearly 1,000-square-foot Japanese-influenced cottage. The result is magical. Even the metal gutter pipes have been covered with giant bamboo.

The cottage is surrounded by pines on six acres of land near the Manuel F. Correllus State Forest and across from the Margaret K. Littlefield Greenlands, a preserve situated over the Island’s aquifer. “This is the best-protected acreage on the Island,” Yans says. She bought the property off Great Plains Road in 1973. “I was the first one on the road,” she says. “It didn’t even have a real road.”

“Why do you need 2,400 square feet?” Yans asks rhetorically. “I wanted to spend my money on the land.”

In 1974 she began building a 1,200-square-foot mid-century modern home on the property that serves as her main house. She built it with assistance from her father, who had a small New York construction business. Friends later urged Yans to add on to that first house, but she opted instead to build a guest cottage with an entirely different feel from her home.

The guest cottage’s connection to the land made an important contribution to how it evolved. “It has a very deep attachment to the place,” Yans says, calling that both healing and “a very Vineyard thing.” “I wanted to preserve the natural landscape as much as I possibly could and, most important, to keep density on Great Plains Road down when a developer and some neighbors were moving in the opposite direction,” she adds. The next stage happened almost ten years later.

“In 1999 we broke through the wall of that little cottage and added what is now the living room.” It grew to 800 square feet, and Japanese elements started to creep in. Her new living room included a circular stained-glass window, along with several arts and crafts stained-glass windows that she’d found in antique stores and markets. The stained-glass windows were fitted with plexiglass to protect them. Because the arts and crafts movement was heavily inspired by Asian architecture, she believed Japanese influences would be a good fit, and the next transition came naturally.

“Since I was a little kid, I was fascinated by Asian culture,” Yans says. Coming from an Italian American immigrant family, she had long been curious about people from different places. Growing up next door to her grandmother, she adds, “I lived in a bicultural world.”

Yans read extensively about Japanese antiques and architecture, and her visit to Japan for a lecture twelve years ago inspired her. “It seemed to me that every time I turned around, I saw something extraordinarily beautiful – from the traditional elite gardens and temples to ordinary farmhouse architecture, which was much more interesting to me,” she says. She returned from Japan with a new handle on how she wanted her guest house to grow.

“The next step brought us to what exists now: from 800 square feet to the just-under 1,000-square-foot guest house,” Yans says. It happened in 2015, after West Tisbury changed the rules about guest house size. “The extra 200 square feet was very important.” It allowed her to add a new wing for a bedroom alcove and a laundry area. To let more light into the living area and help keep the square footage down, the loft’s floor was reduced. “In a house as small as mine, planning and intelligent use of space are crucial,” she says.

She worked closely with architect Keith McGuire, of Keith McGuire Designs, and contractor Billy Meegan, of William Meegan Fine Carpentry, to maintain the home’s arts and crafts elements while incorporating Japanese influences. Meegan and Yans share an interest in Buddhism, and he matched her with McGuire. Meegan and McGuire understood the East/West concept Yans was after.

Both arts and crafts and Japanese architecture have strong links to nature, rely on local products, and have the exposed rafters of post-and-beam construction and roofs that often overhang porches or decks. As McGuire puts it, this blended style “is a celebration of carpenters using those natural materials.” He and Meegan worked to create a pond terrace and roofline that harkened back to Japan.

Yans’s input in the process was strong. A retired Rutgers University history professor, she thinks her experience in filmmaking had a lot to do with her understanding of how to develop and carry through a large construction project such as a house. Among other film projects, she co-wrote the prize-winning 1996 PBS special Margaret Mead: An Observer Observed. It continues to be broadcast around the world.

“Building a house is like making a film,” she says. “You present your ideas, and each person, according to their specialties, adds something of themselves. It’s the ultimate expression of creative collaboration. I knew exactly what I wanted, and the entire team cooperated and did it.”

As an historian who collects antiques and sells them at the Grange Exchange at West Tisbury’s Grange Hall in the summer, Yans has a love of old things. The interior décor of her guest house reflects this penchant. “Being a historian makes me see connections,” she says. “If I suddenly got a chintz couch, it wouldn’t work.”

The interior walls are inspired by the Japanese form of stucco, called wara juraku, but also reflect her Italian heritage. Like Japanese stucco, the Italian form is used inside as well as outside. “It’s a material I love,” she says.

The use of tiles suggests both Italian and Japanese influences. An archway divides the living and kitchen areas and is trimmed with colorful Italian-style tiles. The gorgeous blue-green tiles on the kitchen counters were made by a Japanese American artist and are typically Japanese in glaze and coloring. The tiles on the backsplash are decorated with human and animal figures. They “look like paintings made by children,” suggests McGuire. In keeping with the use of natural materials, a large, rough-cut post in the kitchen works like a decorative element that’s meant to be seen.

The round-topped front door could fit on a fairy-tale gingerbread house. Its wrought-iron hinges and brass knocker make for a front entrance that feels private and yet maintains an intimate cottage-in-the-woods feel. A driveway lined with pines leading up to that door reinforces the sense of privacy. Those pines also make it difficult for trucks to access the space. During construction, Meegan and McGuire adjusted their plans accordingly, using concrete piers under the bedroom/laundry addition instead of pouring a full foundation that would have required the use of big trucks. An added bonus: “You’re not damaging the environment,” McGuire says.

In contrast to the front of the house, the back of the house is open and welcoming, and is dominated by a narrow deck, called an engawa. In Japanese fashion, there are no hallways inside. One living space blends into another, or else you go outside. “You have to walk along the outside to get inside,” Yans says. “Probably the most Japanese aspect of the cottage is the idea of ‘bringing the outside in.’”

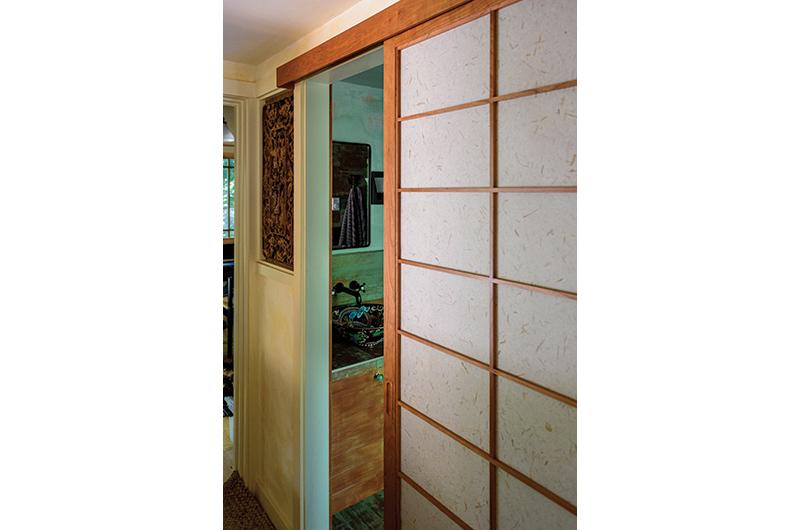

That feeling is enhanced by the use of traditional Japanese shoji: wooden sliding doors with mullions, here incorporating glass instead of paper. Interior shoji are also used to separate the bath and laundry from the rest of the house and even upstairs with a moon window overlooking the koi pond. Japanese friends have told Yans that porches in traditional Japanese houses have a social function. When someone comes to visit, the porch is the meet-and-greet place.

The outside area is dominated by a mini koi pond and waterfalls with water flowing under the deck. It was built by Douglas Assis, chief artist of Jonia’s Landscaping of West Tisbury. Thanks to Yans’s guidance and photos, he quickly understood the Japanese style she was after. He added a low stone wall and rock walkway, both of which encircle the tiny pond and extend the Japanese visual effect even though he used a kind of stone that isn’t Japanese. As Yans points out, the koi can hide under the deck from predators. And the waterfalls provide music to sleep by.

Yans wasn’t trying to achieve an authentic Japanese reproduction, but rather to use what was practical for her guest cottage and for Vineyard plant life. “I take an eclectic approach to garden and cottage,” she says. “The form is very pronounced. It’s all about forms, and the forms are coherent.”

The landscape surrounding the guest cottage is an integral part of the whole, with a mosaic of paths that create the impression of a series of outdoor rooms. “Landscapers like it because it has lots of exciting little things happening,” Yans says. In one corner she’s placed a low marble table with a stool, creating a cozy little spot with an apple tree that becomes a separate part of the property.

Yans thinks too many people make the mistake of eliminating natural vegetation. “You should pick out a tree and clear around it,” she says, and that’s what she’s done. The plantings depend on natural Vineyard flora, and Buddha sculptures enhance the Asian sense of the outdoors, extending the space of the cottage. Meegan calls it, “A land of a thousand Buddhas, a nice little sanctuary for her and the birds and fish.” The result is like a little piece of Takamagahara, the mythological Japanese “plain of high heaven,” tucked into the middle of the Island.