Moses Clayton Hoyle was born in 1886 on a farm in Thompson, Connecticut, and died in 1976 in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. During those ninety years of life, “Clayt,” as everyone called him, would arguably become the best-known Vineyard fisherman of his time. He helped start the Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass & Bluefish Derby and founded the Martha’s Vineyard Rod & Gun Club, invented the precursor to the modern fishing reel in 1907, and the nylon fishing line still in use today. Legend has it that he also started the sport of deep-sea tuna fishing in the early 1900s; until he had a go at it no one had thought to fight a tuna with a rod and reel. And his handmade Clayt Hoyle rods, with the signature rainbow colored wrapping, were known far and wide.

He was also my great-great-uncle.

As a boy I spent summers on Martha’s Vineyard living with my grandparents, Bill and Anne Harding, on Pennacook Avenue in Oak Bluffs, right across the street from Clayt Hoyle. By then Clayt was deep in his eighties. He wore an eye patch over his right eye the color of his own skin, which I found mostly creepy. A black eye patch would have been cool, but this color looked odd to my ten-year-old self. I had heard Clayt had been a considerable fisherman, but I also overheard my mother say one day that he had made fun of my grandfather for not being a very good fisherman. In my eyes, my grandfather was the best fisherman ever, the one who had taught me how to cast and tie a lure, and so for a time I wasn’t so sure about Clayt.

Plus, I was a mere summer dink in those days, the derisive term Islanders gave to us interlopers, a notch above day-trippers but in a sense worse because we had the nerve to call the Island home. I thought I was tough, a New Jersey wrestler used to battling it out all winter in a singlet, but my sport had rules and lived within the confines of a wrestling mat. Islanders lived with no rules, wild children with long hair who in my mind spent the entire off-season training for battle against soft summery dinks.

Who was I to call Clayt Hoyle uncle? Nobody, that’s who.

But age has a habit of sanding down the hard edges, of loosening the reins of insecurity while also shoring up the inner detective determined to examine one’s roots, even if only to rewrite one’s own history.

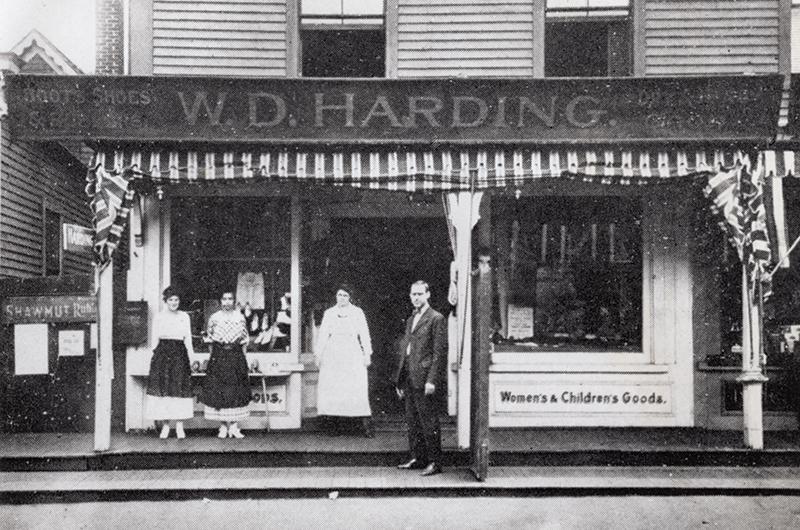

My Vineyard ancestors, the Harding side of the family, were whalers, arriving on the Island in the early 1700s. After the whaling industry collapsed, they became shopkeepers on Circuit Avenue, the store operated by my great-great-grandfather, William D. Harding. It was his daughter Mary that Clayt married, and eventually the two took over the shop. But if Clayt became the premier fisherman on the Island, Connecticut-born but Vineyard made, the rest of the family turned tail and ran, leaving the Island to find work in New Jersey, where I continued in this line, growing up in the Garden State and then moving to New York City for an air-conditioned existence and a life painted urban gray, in contrast with Clayt’s colorful outdoor life.

In 2008 I moved to the Vineyard with my wife, Cathlin, to live here year-round and raise our two children. Cathlin is the minister of the First Congregational Church of West Tisbury, the job that brought us back to the Island. I found a job at the Vineyard Gazette, where I am the managing editor.

Moving to the Island made me think about my roots, and I decided it was time to find out who Clayt Hoyle really was, to do some digging around the Island among the fishermen who may have once fished with the man I had never fished with myself before he died.

“He didn’t have any children so I got dragged along,” my mother, Joan Eville, née Harding, said when I asked her about Clayt one Saturday morning, seated on the porch of her home in East Chop. I had called to say I was coming, and Mom had retrieved two Clayt Hoyle rods from the garage, our coat of arms, and placed them on the porch, their rainbow-colored wrapping glistening in the sunlight.

Dad was there too and asked why I suddenly wanted to know more about Clayt Hoyle. I said I was writing a story, trying to track down a legend in our family tree, the one whose Island roots extended deeper and in more directions than the rest of us combined.

“Oh, so you want to prove you’re not just a washashore? That’s what this is about?”

It is always a bit disconcerting when your family can sniff you out so easily, tracing a direct line to your insecurities. And yet it is oddly comforting, too, this repeated lesson in humility.

“Yup, that’s about it,” I said.

Mom took the lead again, recalling how Clayt would take her to the Flying Horses as well as on fishing trips to Chappy. “He was rough and tumble,” she said. “Always swearing, and no one did that in those days. But no one said anything to Clayt Hoyle. They wouldn’t dare.

“I adored him,” she added.

We kept talking, looking at old photos and reminiscing about family members I knew only by name. It was as if the birds were working and the water filled with baitfish.

Clayt joined my family through his marriage to his first wife, Mary Harding, who died relatively young at age sixty-two. Mary grew up in the house at 85 Pennacook Avenue where I would later spend my summers.

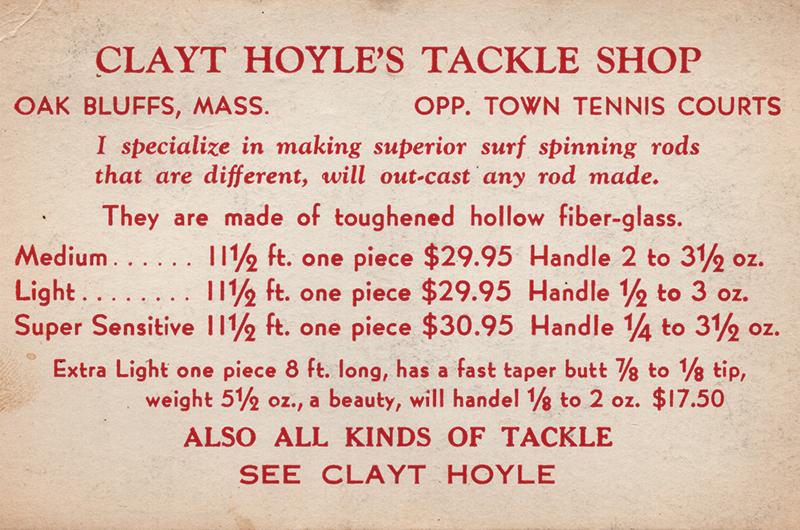

After they married, Clayt and Mary moved into a house across the street and Clayt began working at the family store on Circuit Avenue. And when the rest of the Hardings moved off-Island, Clayt and Mary took over the shop. The Circuit Avenue store closed in 1957, a few years after Mary died, at which time Clayt moved the tackle shop to his garage on Tuckernuck Avenue. In the 1970s he sold it to Dan McCarthy, the legendary football coach at the high school. Dan renamed the tackle shop Mac’s Sports Den, but otherwise left it exactly the way it always had been.

“Dad bought the tackle shop to help put us kids through college,” Mike McCarthy told me when I tracked him down, retired now from running the guidance department at the regional high school.

When I was a kid Mike was my tennis instructor. He and his younger brother Mark carried on the tradition of the Clayt Hoyle rod, learning the craft from the master himself.

“He was a good teacher, but he didn’t have a lot of patience either,” Mike said. “He had no trouble making you do it over. Everything had to be so precise.”

I talked to Mark McCarthy, too, who also taught me to play tennis as a kid but was closer in age to me. On summer afternoons we would sit together outside of the tackle shop, Mark taking care of customers while I watched the courts, hoping someone would need a short but speedy fourth for doubles.

“Remember the moose head?” Mark asked me while we reminisced. “It hung on the wall above the bait freezer.”

I peered into the past and saw myself sitting outside the tackle shop or wandering inside to cool off when the day grew too hot. I saw myself cutting through Clayt’s yard to get to my grandparent’s house, and giving him a wave if he was on the porch. I saw myself walking to the other end of Pennacook Avenue, to where the old library stood, collecting books and reading for hours in the library or on my porch.

And I saw myself walking up Circuit Avenue to the post office, where I would gather the mail, turning the small combination lock this way and that like an upstart safecracker in training, then returning home with the mail, and if it was Tuesday or Friday with the Vineyard Gazette, which I would spread out on the floor and read cover to cover.

But no matter how hard I looked I could not see that damn moose head. Mark told me that after they closed down the tackle shop, the moose head went into the care of his brother in law, William “Bill” Nicholson 3rd. He wasn’t sure what happened to it after Bill died. “Clayt Hoyle! He saved my life,” Cooper Gilkes said without hesitation when I asked him if he had known Clayt.

Coop’s tackle shop is a one-story corridor on the outskirts of Edgartown, small but loaded with gear. A bell rings as you enter the front door and soon Coop or his wife Lela emerges from their home to guide you through whatever fishing needs you have. It is a bit like Ollivanders Wand Shop. Tucked somewhere inside the clutter is your very own dream rod.

Coop was eleven years old at the time and he and a cousin had built a two-man kayak they would take out on Farm Pond. Coop’s grandmother had forbidden them to go any farther.

“Well, saying something like that is like offering candy to a couple of eleven-year-olds,” Coop said. “We immediately paddled out to sea.

“I bet we were four miles offshore,” he continued. “The Island had literally gone away. But then Clayt Hoyle comes chugging along in his boat, out somewhere fishing. He looked at us and said, ‘Looks like you boys could use a tow.’”

Clayt pulled Coop and his cousin back to the Vineyard, saving what would become an essential part of the Vineyard’s fishing lineage.

Coop went on to tell me that Clayt was a quiet guy, thoughtful but not overly effusive. He was a good teacher and listener, especially if the subject was fishing. But many years had passed since that time, and other than Clayt saving young Coop’s life he didn’t have many other stories.

I talked to Steve Amaral next. Steve is eighty-five years old and has only missed one Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass & Bluefish Derby in his entire life. That was in 1956, when he was serving in Korea as a specialist fourth class in the Army’s 51st Signal Battalion and couldn’t come home to fish.

Steve told me that as a boy he used to fish and hunt with Clayt, along with Steve’s father and his uncle Doc Amaral. He confirmed Clayt was relatively taciturn but friendly.

At one point Steve got up from the kitchen table and left the room. When he returned he held a fishing plug, a sloping-shaped white plug about six inches long. It looked old but the eyelets were still in good condition with barely any rust.

“Clayt was sure this was going to be the next big thing in plugs,” Steve said. “He gave it to me when I was a kid at a discount to go out and try it.”

“And how did it work?”

“Terribly. I never caught a thing with it, but I saved it all these years. Didn’t really know why, but I might as well pass it on to you.”

We talked for another hour, not so much about Clayt specifically, as Steve had been just a young boy in those days. Instead, the talk flowed from fishing to his plumbing career, his years as a fireman, and the ones that got away.

He pointed to a monster striped bass mounted on the wall.

“I caught that one in 1978,” he said, “56 3/4 pounds. It would have been the Derby winner that year, but I caught it two days after the Derby ended. Isn’t that something?”

I was holding Clayt’s plug while Steve told the story, passing it from hand to hand, imagining the scene of Clayt giving the plug to Steve to this scene today of Steve passing it along to me.

“Yes,” I agreed. “That is something.”

I would have happily sat in kitchens and living rooms around the Island for years, hearing about the old days from men with thick, leathery hands and iconic faces that would have looked at home on all manner of currency. But each fisherman had mostly the same thing to say about Clayt: he was a good man who loved the Vineyard, quiet and demanding, but kind, too.

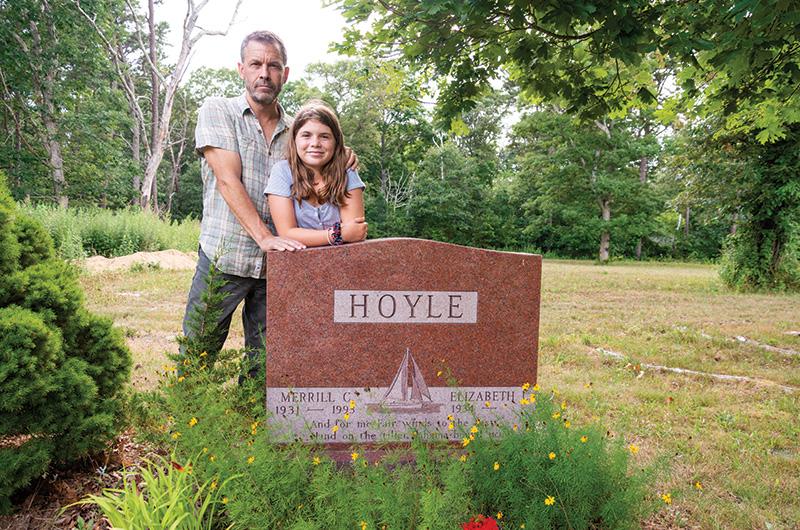

It was time to go where all dead ends eventually lead: the graveyard. My mother told me Clayt was buried in the Oak Bluffs cemetery, but she didn’t know exactly where. And so on a Saturday morning, I joined a cemetery tour led by Tom Dresser. I brought my eleven-year-old daughter with me.

Pickle, a nickname she acquired in the womb, spends at least one day a week after school at the Gazette office and periodically accompanies me on assignments. She understands the power of walking around with a pad and pen and likes to write down lists of details that she urges me to use in my stories.

“Why don’t you add that a bird named Ed flew by while you were interviewing that lady with the guitar,” she has asked.

And yet going on a cemetery tour was not at the top of her list of things to do on a summer day. I convinced her by explaining we were gathering clues about our family history. I also promised her a double byline.

“Research assistant,” she suggested.

There were about fifteen of us on the tour, the average age deep in the sixties, with Pickle as the outlier doing cartwheels and roundoffs while we walked among the rows of headstones. When we stopped at the grave of Tom Clancy, the famed spymaster novelist, Pickle drifted away.

“Dad,” she called from a headstone nearby. “I think I found him.”

Sure enough, the Hoyles and Tom Clancy were neighbors in death. We stood before the Hoyle headstone as the tour gravitated to us. A murmur went through the crowd when they found out I was related to Clayt.

“Greatest fisherman the Island has ever known,” a tall man exclaimed, adding that he had two Clayt Hoyle rods at home.

Others agreed, testifying to their Clayt Hoyle rods, and suddenly Pickle and I were Island celebrities. As I was basking in this newfound splendor, Pickle called out again.

“Dad! I think this lady buried with Clayt is still alive.”

I looked closer at the Hoyle headstone, which listed Merrill C. Hoyle, who was born in 1931 and died in 1993, and so was not Moses Clayton Hoyle after all, but his nephew, Clayt’s frequent fishing companion. The other name on the headstone was Elizabeth Hoyle, born in 1934 but with no death date inscribed.

“Oh sure,” a woman on the tour said. “She lives down the street from me, not far from here. Everyone calls her Betty. She’s still sharp as a tack.”

Two days later, Pickle and I showed up at Betty Hoyle’s house, which overlooks Sunset Lake and the Oak Bluffs Harbor. An old woman came to the door and looked me over warily, not budging when I told her I was from the Vineyard Gazette and Martha’s Vineyard Magazine doing a story on Clayt Hoyle. But when I moved Pickle front and center, I saw the doorknob turn.

“Come on in,” the lady said to Pickle. “And I guess your dad can come in too.”

We were led to the far end of the kitchen, to the breakfast nook, and sat down at a small table.

“Betty is out now at church, but what can I do for you?” the woman asked. I repeated that I was working on a story about Clayt Hoyle.

“And Betty’s name was on a headstone only there’s no death date,” Pickle said.

“Well, that’s because she is still alive,” the woman said.

“And are you her caregiver?” I asked.

“No, I’m her younger sister, Barbara. We live here together. Betty is in much better health. She still drives.”

Barbara went on to tell us that the names on the headstone were her brother, Dr. Merrill C. Hoyle, and his wife, Elizabeth Hoyle, who is still alive and living off-Island. Her sister is also named Elizabeth Hoyle (and goes by Betty) and at that moment she pulled in the driveway, driving home from church at age ninety-six.

Soon enough Betty joined us at the table and the four of us spent hours together, talking about the past, fitting puzzle pieces in where they needed to go, and adding more scenes as they came up. The house was located not far from where my great-grandfather had moved to, after returning from New Jersey to live out his days on the Vineyard. My brother and I would roll down the hill during visits, daring each other to go as far as possible without falling into the duck pond. But we had no idea that a few blocks away, on Elizabeth Way, there lived another branch of the family.

Both sisters had known their Uncle Clayt Hoyle well and confirmed that he was laconic but kind, that he hunted and fished and that they, too, had a Clayt Hoyle rod. They had never fished or hunted with him, though.

“That was back when men were men and women stayed home,” Betty said, adding that their brother Merrill had gone on many fishing trips with Clayt.

My great-aunts told me that Clayt had an automobile business back in Connecticut, which went under when World War I started and all the mechanics were drafted. Then he became a chauffeur for the family who made Corbin Locks, based in New Canaan, Connecticut. The family owned a house on Ocean Park, the one now owned by Peter and Gwen Norton. This was Clayt’s introduction to the Vineyard.

“I saw in some article where they said he was rich,” Barbara said. “But he wasn’t, and that burned me up that they said he was. He was a chauffeur after all.”

The conversation moved about like bumper cars, nudging up to Clayt Hoyle and then ricocheting out again to their lives, separate from my uncle. Clayt had introduced the Island to his father and his brother (my great-aunts’ father) and the whole extended family moved here. My great-aunts graduated from the Oak Bluffs School and then made their living off-Island – Barbara as a nurse, Betty as a counselor for alcohol and drug treatment programs. Barbara had never married and Betty had married her childhood sweetheart Bob Penney. They later divorced, but when Betty moved back to the Vineyard they had rekindled their relationship in their seventies.

“They’re dating,” Barbara said.

“We had both remarried but our new spouses had died,” Betty explained. “We laugh about our journey now. Forever after, but in between there’s a whole other history. I guess you can go home again after all.”

My great-aunts brought Pickle into the conversation circle, too, and despite the age difference, their connections were more tangible than mine as they swapped tales of the Oak Bluffs School in the 1930s and 1940s and the West Tisbury School of today, where Pickle is a seventh grader. Then, as now, basketball between the towns drew battle lines at the borders.

“That’s when the towns began to hate each other,” Barbara said, referring to the origins of the basketball rivalry.

“We don’t hate each other now,” Pickle countered. “But we like to beat them.”

It struck me then, watching my daughter and great-aunts trade Vineyard tales, that she was an Islander, maybe not born here but brought here at six months of age to live and grow up, and that I, too, had made the choice to live here, not in retirement like my parents and grandparents and great-grandparents, but to work here and raise my family. I may not have become an outdoorsman like Clayt, but I had made the same choice he had, casting my lot on this rock.

Growing up in New Jersey I always knew I would leave, and when I did, moving to New York City after college, I thought I would never live where my past had lived, never walk with the ghosts of childhood peeking around every corner, arm in arm with my ancestors. But here I was doing just that, as sure as the scent of a privet hedge in spring will always put me on the front porch of my grandparents’ house on Pennacook Avenue wondering who I would become, while across the street Clayt Hoyle had done the same thing.

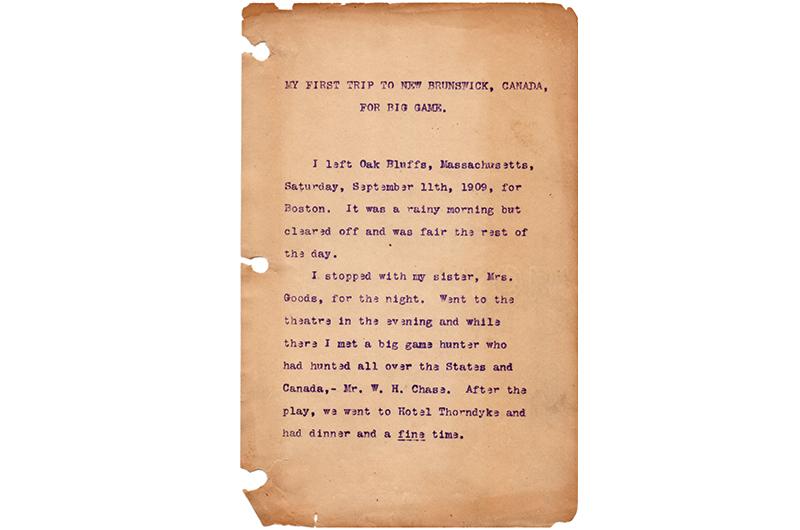

As I pondered these thoughts Betty rose from her chair to collect more old photographs and other pieces of paper, which turned out to be Clayt’s journals. I began leafing through a particularly ancient one, yellowed with age, the paper coarse and fragile. I turned the pages slowly at first, taking care while I read words written in Clayt’s own hand. But then I saw the moose, both a photograph of a young Clayt Hoyle astride the huge animal and his typewritten account of the trip.

During my interviews I had tracked the moose head to its final resting place, mounted on the wall of the Martha’s Vineyard Rod & Gun Club in Edgartown. After Bill Nicholson died, his buddy Brian Welch housed the moose head, where it suffered the indignity of living on his basement floor among the cobwebs until a friend saw it and told him the hunter was a legend on the Island and that the moose head needed to be displayed in public.

In Clayt’s journals he described how he traveled to Canada for the moose hunt.

“I left Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts, Saturday, September 11, 1909, for Boston. It was a rainy morning but cleared off and was fair the rest of the day.”

In Boston, after going to the theater, he met a big-game hunter, and from there they headed to New Brunswick, Canada, where he found his moose.

I was reading quickly now, turning pages so fast Barbara had to stop me.

“Be careful, that journal is over 100 years old.”

I slowed down then, savoring the journey of the moose hunt, and then backtracked to other tales written about smaller hunting excursions here on the Vineyard, for rabbit and duck with Doc Amaral and other buddies. I traveled with Clayt as he fished and hunted, and in most entries there was a tally given of the day’s take, along with the particulars of a difficult shot.

The morning with my great-aunts stretched long into the afternoon, and Pickle and I have gone back many times to talk and continue a relationship I never knew existed.

As for Clayt Hoyle, I finally had to put the article to bed, even with more bread crumbs out there, surely leading to additional confirmations of my great-great-uncle as a laconic legend. Clayt moved to the Vineyard and made the Island his home in ways that made me feel both a lesser man and proud of my lineage.

A few weeks after I turned in this article, Pickle asked when we could go out again to work on the story some more.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I finally had to turn the piece in.”

“Oh, bummer. Did I get my credit?”

“Yes, you did.”

“Thanks, but why can’t we keep doing research? Why does it have to end with the article?”

I thought for a moment and realized she was right, it didn’t have to end. We could still chase some more leads.

“Where should we start?” I asked.

“How about that Bob Penney guy, Betty’s boyfriend who used to be her husband,” Pickle suggested. “He lives in the Camp Ground.”

“Good idea,” I said. “I’ll call him right now. And then I have another idea.”

“What’s that?”

“Let’s go fishing.”

8 comments

8 comments

Comments (8)