Most mornings we walk. A text goes out – Just finishing my coffee…where do you want to go? Within the hour we’re at a trailhead, dogs bursting from the backs of our cars, off to sniff in the underbrush. Elizabeth and I have been friends since we were little girls. Our conversations are easy, intimate, the way it is for people with a long-shared history. In better times, we’d be catching up on the news of a week or a month. These days we measure our absence in hours and the talk is granular, almost continuous. We’ve barely been out of each other’s sight since quarantine. Our houses, the same ones in which we spent childhood summers, are separated by a wildflower garden and a hedge, still barren this time of year. At six o’clock we meet again for a glass of wine on her porch. Bundled against the record-cold spring, we share dinner menus, fresh news from distant friends, the president’s latest act of mendacity. And always, always, we talk of the virus. One evening in mid-March we ate dinner together with a small group of friends. Within days, each of us developed symptoms of Covid-19. On the Vineyard, where fear has turned othering on its ear, we have been an island within an island, warily watching the restless tide.

The Vineyard isn’t my full-time residence. But it is, in the deepest sense, the place I consider home. In the late 1950s, my parents, Bill and Rose Styron, began renting on Vineyard Haven Harbor for a couple weeks each summer. One day, Carl Cronig let my mother know that the house next door, a place she’d long admired, was going on the market. After a quick call to my grandmother, who agreed to front her the deposit, Mum raced over to Carl’s office with a cashier’s check. That property – a slope-floored old house with a big lawn and a couple of outbuildings – has been the center of our now-sprawling family’s life for three generations. We’ve been married here and christened here, rung in the new year and passed the Thanksgiving turkey. My brother Tom was born at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital sixty-one years ago. My father died there in 2006. Dad’s buried in the little cemetery up toward West Chop, right next to Elizabeth’s parents, Lucy and Sheldon Hackney. Beside them lies their eldest daughter, Virginia. Despite her intellectual disabilities, Virginia was able to live an independent life here for years – biking, ice skating, starring in Camp Jabberwocky plays – under the loving eye of the local community. Eventually, all the Hackneys settled on the Vineyard year-round. Lucy and Sheldon’s proximity was central to my mother’s decision, after my father’s death, to move here full time too.

I was thinking about my mother as I left Brooklyn on Friday the thirteenth of March. At ninety-two, Rose Styron is still a singular force. A poet and a human rights activist, mother of four and widow of a celebrated writer, she’s lived a life rich with experience and adventure. Though her physical pace has slowed a bit, her appetites remain undimmed. She continues to attract friends and admirers, to be an expansive hostess, to travel off-Island and all around it. She had just spent a month in Florida and had been back and forth to Manhattan. On the drive to Woods Hole, I wondered how she would stand having her wings clipped. Shelter-in-place orders on the East Coast were still more than a week away. But in New York, her most frequent destination, the virus was catching fire. When would she be able to go again? How?

In the passenger seat, my daughter Martha (named for the Island, though she likes to be called Sky) folded in on herself and stared out the window. The day before, her school announced it would be shutting its physical doors. My son Huck, his school’s band trip to Europe cancelled, was already on-Island with my sister in law Phoebe. We had planned this weekend a while back. Suddenly, what was supposed to be a few days with extended family was looking like a trip with no definite return. Still, we didn’t pack much. My husband was in Atlanta where his father had just undergone bypass surgery. Surely we’d all meet back up in Brooklyn…soon?

Sky wore her earbuds; I listened to NPR. Somewhere between Providence and Fall River, President Trump declared a national emergency.

Arriving at “the little house” (a cottage next to my mother’s house where my siblings and I live when we’re here), things looked familiar enough. Huck and his cousin Tommy were in the back room playing Madden. Phoebe was putting on dinner for her younger son. A charming slip of a boy, Gus was born with profound special needs including some manageable but persistent health issues. Phoebe’s love is fierce and her vigilance constant. In January, we went on a girls’ vacation with a group of good friends where it was great to see Phoebe really unwind. Five of the six of us were reuniting that evening at Elizabeth’s. We were expected any minute. I told Phoebe I’d be ready soon and ran across the lawn to check in with my mother.

I found her in her favorite spot at the kitchen table, looking over some papers. Bill, her live-in helper, was tossing a salad.

“Hi, Mum,” I shouted from the doorway, in case she wasn’t wearing her hearing aids.

Seeing me, she lit up and began to pull herself out of her chair.

“Stay there,” I said, waving her away. “I’m not coming in.”

“Why?” she asked, frowning. And then cheerfully, after a beat, “Oh! It’s okay! I’m washing my hands all the time.”

“I’m not worried about your hands,” I replied, sharing an amused look with Bill. “I’m worried about mine.”

It was an exchange we’d have several more times in the coming weeks. From anyone else her age, my mother’s persistence would seem dotty but actually comports perfectly with the woman I’ve always known her to be. Mum fears nothing for herself and never has. She works her optimism like a scythe, seamlessly clearing the path ahead and laying waste to shadowy intruders.

Bill offered me some extra pasta.

I fed my kids and brought the rest of the bowl through the break in the privet hedge.

What do I remember about that dinner? How do you siphon memory from significant moments that, when they were unfolding, didn’t seem to matter at all? As I recall, the evening was tempered but nice. Did we hug? I don’t think so. But we definitely shared cheese and crackers. Kelley, who lives on the Island year-round and is a field producer for ESPN, was in a fatalistic mood. She’d been on the road covering the NBA for months and had suddenly been furloughed in the wake of the season’s abrupt suspension. Marilyn, who was selling her off-Island house, told stories from Mardi Gras, a celebration she never misses in her native town of New Orleans. Elizabeth had just come back from visiting a daughter in California; Phoebe was up from New Haven; and I, well, I had come from New York City. In the coming weeks, our status as Island residents – two full time, two part time, one in the process of moving here for good – would silo us in unexpected ways. But that night we were just a bunch of friends getting together for a bite. We were neighbors.

Every writer’s got their thing. A ritual or vice that helps them settle into work, like a dog circling his bed before sleep. Colette used to pick fleas off her French bulldog. Graham Greene couldn’t write a word until he’d accidentally come upon a specific string of numbers each day. Oscar Wilde, Samuel Beckett, and a jillion other authors chain smoked their way to immortality.

I read Facebook and eat Gummi Bears.

In the first strange days here I tried to maintain some semblance of discipline. My husband and I decided it was best for the kids and me to stay on the Island. Phoebe was staying too. My brother and niece came up to join them. With CNN blaring and children darting everywhere and a vibe somewhere between Christmas and the Apocalypse, I retreated upstairs to “work.” But mostly I just drank from the Internet fire hose: 2,700 Covid-19 cases nationwide. 2,500 dead in Italy. Schools closed in North Carolina, Arizona, Connecticut. The first death from the virus in New York City. On the Facebook group Islanders Talk, I caught the first volley in what would become a holy war over summer people and hospital beds and the spread of contagion on an Island with limited resources. The underlying concerns were perfectly legitimate. I could almost feel the fear rising from my laptop. I was scared too. But the conversation was ugly and reminded me, ironically, of one in the same group about immigrants during the height of the border separation crisis. Taking umbrage, I waded into the thread briefly, and immediately regretted it. Mostly I sat on the sidelines, dumbstruck and slightly wounded. They’re not talking about people like me, I thought. Are they?

I put away my car with its conspicuous orange plates and began to drive my mother’s old Subaru.

All the while, Mum remained sequestered in the big house with Bill who, at seventy, is also high risk. On group texts with our sisters, Tom and I tried to balance the potential for exposure with the guilt we felt being huddled in one house while the family matriarch was untouchable in the other. I put on surgical gloves and joined her for a game of Scrabble. One night we got takeout from The Cardboard Box and ate it seated as far away from her as possible. It was a brief and chaotic meal – grilled chicken with a side of Clorox wipes – but Mum was delighted and pleasantly oblivious to the worries the rest of us shared.

And here’s where the story picks up some speed, though I struggle still to nail down the plot. There’s a fog-of-war quality to this pandemic. Sometimes it’s hard to know what’s happening when you’re in the middle of living it.

On Tuesday, March 17, I made a garlicky kale salad that, I noticed, didn’t taste like garlic at all. My Gummi Bears were dull nuggets of rubber. I looked for a sell-by date, shrugged, and put them in the drawer.

On a group text Wednesday, Kelley reported she’d been feeling kind of punk.

On Thursday, Elizabeth wasn’t feeling great either. Outside the little house, I picked up after the dogs, pausing to sniff tentatively at the bag. Phoebe saw me through the living room window and laughed.

On Friday, the board of health announced the Island’s first confirmed Covid case. A man in his fifties from (groan) Brooklyn. Tom and Phoebe weighed whether Gus would be safer on the Vineyard or in Connecticut.

By Saturday, Elizabeth was up and about. It was just a passing thing, apparently. “I’m going off my allergy medication,” I told her, as we sat on her porch. “My taste has gone funny, and I can barely smell anything.”

“Hmm,” she said, staring at her hands, “that’s weird. My taste seems kind of off too.”

With the benefit of hindsight, of course it seems insane that we weren’t more alarmed. But then I remind myself that back then, few of us understood the magnitude of the crisis. In mid-March, sneezing in public was late-night joke material, our Instagram feeds were still full of toilet paper memes, and no one, in the U.S. anyway, had heard of smell and taste loss as a symptom of the coronavirus. Believe me, I Googled it for days.

As we would learn later, Kelley spiked a fever on Thursday and Friday. By the end of the week her husband, John, was sick too. On Saturday morning she drove to the hospital for a Covid test. The triage nurse told her she didn’t qualify and sent her back to her bed.

Around sunset on Saturday, my phone pinged. A text from Elizabeth appeared, linking to an article that had just been posted on forbes.com.

I stared at the headline – “There’s An Unexpected Loss of Smell and Taste In Coronavirus Patients” – thought of Gus, and felt my head swim.

Scientists say anxiety affects the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for thinking and planning ahead. Maybe this is why I fell silent for several hours, unable to figure out how to tell my family what I suspected. Tom and Phoebe were going to leave. Maybe, I thought with Trumpian logic, the whole problem would just magically go away!

Trying to overcome my cowardice, I began planning the words I’d say. But before I could get them out, Phoebe took me aside and told me about an article she’d just read in the U.K. paper the Daily Mail. I gulped hard. And then she whispered, “I can’t taste anything either.”

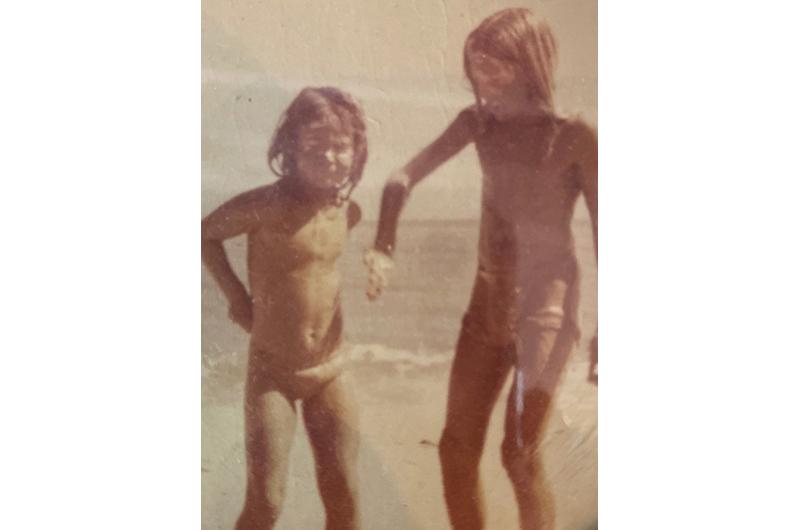

When we were little, Elizabeth and I used to walk into town nearly every day. At Leslie’s, we bought Bazooka gum and comic books. Then we dipped into Ben Franklin’s for rainbow-colored yarn, maybe a prank or two, those fake cigarettes that released a cloud of talcum powder smoke. Or we went to the library, coming home with arm loads of books to be read on the hammock, lying top-to-tail. When I was six and Elizabeth eight, one of us (okay, me) had the idea to hitchhike the quarter mile up the hill. I still remember how excited we were when the very first car, driven by one of our neighbors, screeched to a halt at the sight of us. Back then we were armchair scholars of Archie and Veronica, Deenie, Ramona the Pest. Now, segregated by our condition, we were a roving dialectic on the plague. On empty paths in relentlessly awful weather, we shepherded our canine flock while positing theories, sharing data, spinning potential scenarios for us and for the world. Elizabeth had heard that loss of smell was a precursor to the virus. I advocated for my sources which had the symptom showing up late – mostly because it comforted me to think the worst had passed.

As the days ticked by and we got no sicker, we obsessed about obtaining antibody tests. How else, we wondered, would we know we were healthy again? How would we know we were done? Sometimes Elizabeth felt tired and took long afternoon naps. I, meanwhile, had nothing more than a nagging headache and some night sweats – in other words, Tuesday for a woman my age. Looking back, I suppose there were some other subtle early signs. One morning, before I lost my taste, I woke up, blew my nose, and found a bright red clot of blood in the tissue. My eye sometimes twitched. My gums ached. But, when everything is a symptom, as it is with this virus, what do you pay attention to? And when you can’t get tested, how do you decide you’re actually sick?

My lungs were clear and my body determined. But my head was, frankly, a mess. It’s not that I was afraid for myself. My husband calls me a cockroach for a reason. But I couldn’t stop perseverating on whether I could have sickened others. As Kelley says, the guilt is as exhausting as the virus. I tried to remember every time I’d entered my mother’s house, every person I might have stood too close to. My son developed a chest cold that I was certain indicated infection. My mind spun with the rotors of each MedFlight helicopter taking off over the harbor.

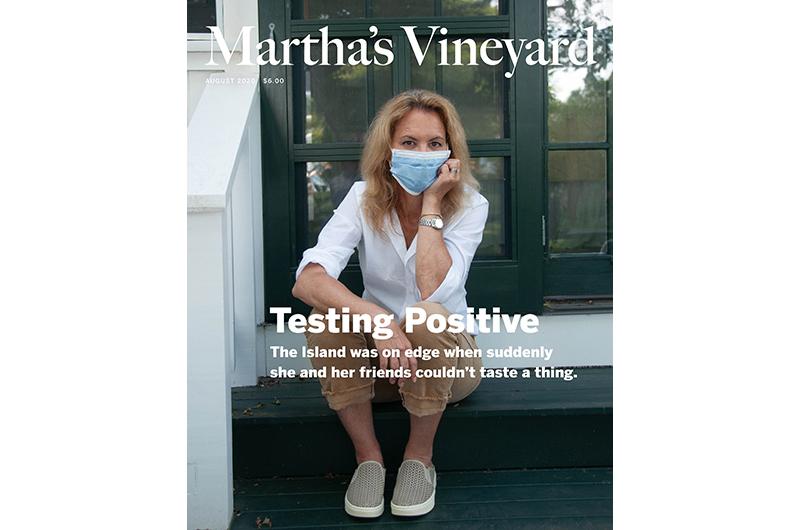

I also found myself uniquely isolated by the liminal aspect of my citizenship. In early April, Elizabeth and Kelley were the anonymous subjects of an article in the Martha’s Vineyard Times titled “I Was Not Sick Enough To Be Tested.” Both women considered going on the record – indeed, they’d reported themselves to the local board of health as soon as they became ill – but the chatter on Island was so Salem-Witch-Trial-y they decided against it. (All the people in this story gave me permission to use their names, a decision Kelley attacked with the same enthusiasm she does the tennis net. “Tell them I was Patient Zero!” she shouted, advancing our unproven theory. “And pour me another glass of wine while you’re at it.”) As for me, I kept a low profile. Back in Brooklyn, my husband described the awful symphony of sirens. When the few people whom I told expressed sympathy, I didn’t know what to say. I wasn’t sick. But I wasn’t entirely normal.

On Sunday, March 22, the day after our self-diagnosis, Phoebe and her family drove back to Connecticut. The house grew quiet and a cold rain fell. I began studying my hands as I used them, washing them over and over, staring at the kitchen counters. I made dinner and put out plates for my children. After eight days in our petri dish of a house, it was too late to isolate from them, but I needed to do things differently for a sensible amount of time – a measurement that, with no fever, I’d have to determine on my own. I told my kids I thought I had the virus because I couldn’t smell. They were incredulous, skeptical, but, by dessert, receptive and subdued. That night I went to bed feeling relatively calm. We were going to be okay, I thought. We just had to ride it out.

Just before dawn the next morning my phone rang. Bill’s name flashed on the screen. “Sorry to bother you, Al,” he said in his typically gentle voice. “I can’t stand up. I think I need you to call me an ambulance.”

I remember asking him if he had a fever, to which he replied no. I remember calling 911. And I remember thinking, “Well, here we go.” When the ambulance arrived, I was standing on the porch in the rain, wearing, I realized, nothing but my nightgown. A burly EMT climbed down from the cab and scanned the driveway, looking for the best way to position his rig. He looked at the cars and backed up a step. “Who’s from New York?” he yelled. I pulled the neckline of my gown over my mouth and identified myself, then directed him to the other house. His voice sounded angry. But when our eyes met I was sure I could see fear mirrored back at me.

Yesterday, Elizabeth and I went to Chappy. Our walks are more expansive now and the world around us is turning green. In early May, we finally got our antibody tests (for those of you keeping score with the board of health, we were the first “suspected cases” no longer harboring the virus). So did Kelley, Marilyn, and Phoebe. The results, which we trust, were both predictable and surprising. Everyone but me in my family tested negative. According to the doctor’s office that processed my labs, my viral load was probably too low to be infectious. The results were the same for Elizabeth’s family, and for Phoebe’s. (Marilyn was barricaded by her college-age children in her room for fourteen days for what turned out to be a pesky case of strep).

Bill had a minor heart issue, but is back on the job. And my mother remains as astonishingly healthy as ever.

In this terrible season of loss, I still can’t fathom our good fortune. But now Elizabeth and I have new things to discuss. New week, we’ll hang up our walking shoes and drive to Providence to donate convalescent plasma. Just a quick trip, then we’ll head back to the Vineyard. Back home.

22 comments

22 comments

Comments (22)