I meet Charlie for coffee. We sit inside the cramped quarters of Espresso Love in Edgartown – our conversation competing over others and our coffees vying for space on the table in the days before social distancing. “Do you want to sit outside – more space?” Charlie asks me. “If it’s not too cold for you,” I offer politely. Charlie half smiles and pushes his way through the door to the canopied deck. Charlie Blair went to the Arctic on a steel ketch. Charlie Blair races ice boats. Charlie Blair was a commercial fisherman for twenty years. Charlie is presently the Edgartown harbor master. No, Charlie wouldn’t be too cold.

I speak with Charlie for two hours, our coffees chilling quickly. The conversation is easy – Charlie smiles and laughs frequently while retelling events from his past. This is not the harbor master I expected. Lacking was the impatience with inexperience, the sighing at stupid questions, the long silences that I was accustomed to when talking to my grandfather, the closest approximation of a Charlie Blair that I could imagine. Charlie’s appreciation for, and love of, the sea was almost matched by his pleasure in indoctrinating new souls into life on the water. Where I expected crusty, I got humor. Where I assumed curtness, I got a willing storyteller. Charlie himself was the story, really, his life best told in chapters in order. Boy. Teen. Young Adult. Man. Sea Salt.

I realized quickly, however, that I would only be able to offer the bare minimum of the story – a brief outline bereft of the details that I imagined were salty, possibly even sordid and raunchy, but also poignant and heartbreaking. The story I could tell would be shallow but still rich enough, because even an outline of Charlie’s plot would be more interesting than a thousand-page exploration of another’s life. Herewith then is my story of Charlie Blair – a life in 2,000 words.

Chapter One

“They Just Kinda Let Me Go”

Charlie was born in Miami Beach, Florida, before moving to Coconut Grove at an early age. Summers, however, were spent on the Vineyard out in Katama, where his father had purchased property. There were fewer than a half dozen houses at the shore, and none heading back to town. But there were plenty of cousins – the Robinson kids (the matriarch, Louisa Robinson, owned the Dr. Daniel Fisher House for a stretch). Keeping Charlie in their peripheral vision, secure in the knowledge that surely someone would notice him gone too long, they let five-year-old Charlie roam free. He sailed, he swam, and he sailed some more. “They just kinda let me go,” Charlie says. Ah, the good old days.

Chapter Two

Saving Lives and Sailing Boats

By a young teen, Charlie had already firmly entrenched himself in Edgartown teen society. Like any smart grandson, he recognized a good thing when he saw it, and parlayed his maternal grandmother’s purchase in the ’30s (and his father’s later) into a permanent spot on the Island. He raced sailboats with his father and lived his life on the water – the sea and him forever bound in a complicit agreement of mutual respect. Then, presaging his later career, Charlie took on the duties of assistant harbor master. In this capacity, Charlie again was given a long leash.

“One time,” Charlie begins, grinning at the memory, “I was the first on the scene of an accidental meeting between a young lady’s leg and boat prop. She was bleeding heavily. I knew enough that I had to stop the bleeding, so I began tearing my clothing into strips to tie off her thigh in a tourniquet.” By the time professional help arrived, Charlie was nearly nude in the water, and the girl was festooned with dozens of tourniquets. “The ambulance back then was an old station wagon, so it wasn’t the ‘quickest way around,’” Charlie tells me in a way of an excuse for the relative tardiness of the adult help. The young woman will live, Charlie was told as they carried her into the back of the wagon, its seats folded down to accommodate a prone body.

“Thanks, Charlie,” they said. Then they all left, leaving Charlie to a quiet lone nudeness, waist deep in water. Thanks, Charlie.

Chapter Three

Jaws, the Arctic, and

Racing to Nassau

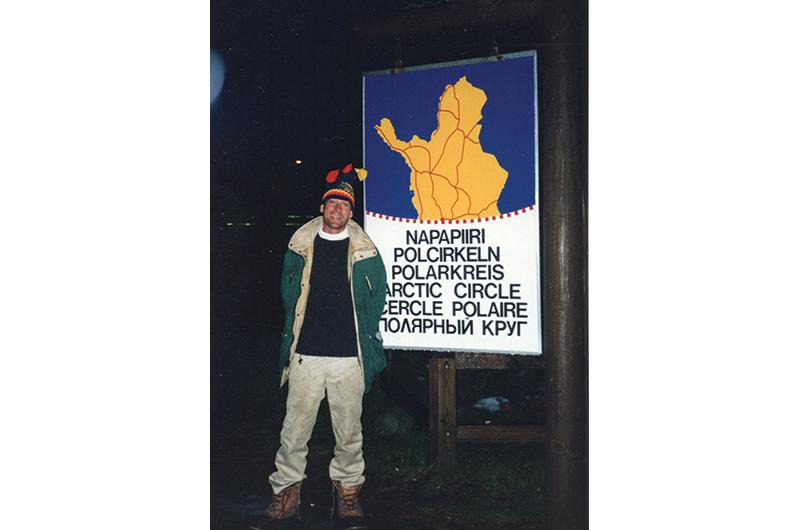

Out of college (a period which Charlie appears to dismiss with the wave of his hand), Charlie was approached by George Moffett (a founder of the Holmes Hole Sailing Association) to captain a steel ketch, the Snow Goose, to the Arctic. Sure, why not. The year was 1973. But the trip temporarily fell apart in the building stages of the ketch, so Charlie stayed anchored.

“So, you never got to go?” I asked, assuming such a project probably doesn’t get resurrected. “No, we went,” Charlie says casually, as if he were just driving a girl home from Boston College. Charlie captained the Snow Goose Arctic expedition to and fro, taking on cook’s duties along the way.

“I wanted good meals,” Charlie shrugs. And that was that. Charlie never expounded upon their adventure or provided details of the trip. He went to the Arctic and back – another day’s work for a young Charlie.

The next logical step was then to take over all the on-water duties for Universal’s production of Jaws. “The Ruddy Duck [a charter company in Edgartown] hired me to run a boat for half a day at the start of filming, but by day’s end I’d been hired to run the whole shebang for the length of the shoot. Apparently the teamsters weren’t as familiar with the ocean as they were the land. I gathered a crew of locals, rotating the sober ones with the passed-out ones.” Charlie worked twenty-two-hour days. Charlie made a ton of money in a little over a month’s time. He took this cash down to Miami to race his sloop, Hotfoot, in the Southern Ocean Racing Conference, because, well, of course that’s what he would do. He won his class in the Miami/Nassau race, and then...did a bunch of other stuff.

Chapter Four

Commercial Fisherman

Perhaps feeling the need to settle and find more steady employment, Charlie built his renowned boat, Nisa, from out of the narrow interior of a chicken coup in Virginia. I say “perhaps” he did because I really don’t know. These next twenty years are run through as if I am keenly familiar with the life of a commercial fisherman (I am not). I do know that he fished cod, bay scallops, and shellfish, and he did well. Suffice to say that he was a commercial fisherman. Case closed; the topic for another story, another time.

Chapter Five

Charter Boat Captain

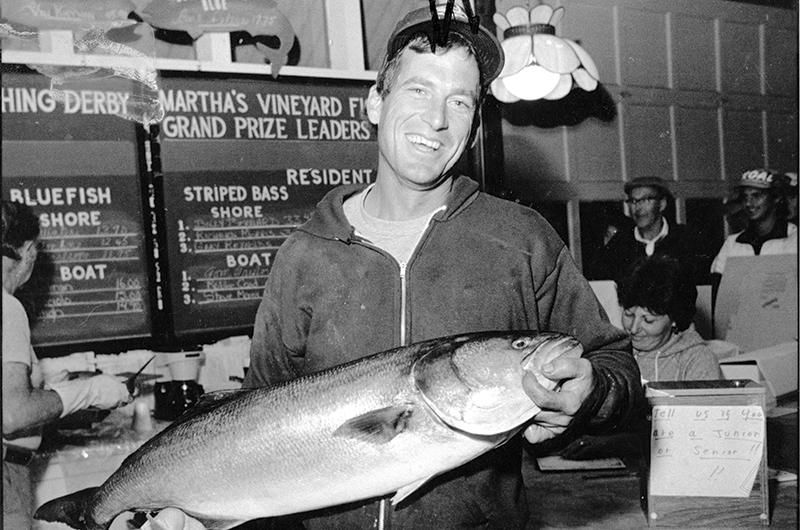

Again, we don’t linger here. What I do know is charter boat fishing is a lot like commercial fishing but easier and with less swearing. His son Wolfie and

daughter Scarlet would go out with him, especially during Derby time (they’d leave the Edgartown School at 2:10 and be on the boat by 2:30). Most visitors to the Island that are at all interested in fishing know Charlie and his boat Nisa. He was the go-to guy to catch fish. Several of my friends who visited me went fishing with Charlie, most unable to contain their disappointment that I, their host, wasn’t more like Charlie. Charlie knew where the fish were biting, but if by chance he missed them, he was tipped off by other boats as to where he might like to fish next. That is how well-liked and respected Charlie was: normally mute fishermen let loose their lips to help out a friend. And this could have been Charlie’s last chapter, but it is not.

Chapter Six

Harbor Master

All those years on the water, all that experience – good and bad – has led Charlie here to this latest chapter. Who else would you want patrolling the water than someone who has salt in their veins? Charlie needn’t think a whole lot when a crisis develops. He can act and react with the muscle memory of a tennis player who has hit 100,000 balls. Charlie is often the first on any scene, applying duct tape (literally and figuratively) until other professionals arrive. Then Charlie motors away so he’s ready for the next event.

“Mostly now, though, I get calls about a broken wrist or hip because of a trip or slip. Or maybe the wrong medication taken at the wrong time.” The population of the harbor has aged with Charlie, who these days has replaced beer with milk and bars with the Y. Still, Charlie will get calls of a passed-out bather (her friends seemingly having disappeared upon his arrival) who needs some serious attention. “I poke them in the eyeball – if they don’t blink then I know they’re more than two sheets to the wind,” he tells me. Sometimes boats catch on fire; sometimes boats sink or lose their power. Charlie will be there to help. And on very few occasions someone will go missing, resulting in either the absolute high of recovery or the crushing lows of loss. Charlie carries these losses with him – a crease or two aside his eyes a testament to the enduring sadness.

I ask Charlie about race weeks and regattas when the activity in the harbor and outer harbor seems to double. Are these difficult times? “Not at all,” he says. “Sailors police themselves – they know of the whereabouts of all their respective members. Plus,” he adds, “they all check in, and we now have a database of all the sailors present during any such week.” In fact, Charlie has in his database a record of anyone and everyone who enters his harbor. Far from resisting emerging technology, Charlie embraces it. “Now I know the exact time a boat is on a mooring, and the time it leaves.” This knowledge makes managing the harbor and its boats more efficient. And profitable. Charlie has more than tripled the revenue of the harbor during his tenure. “I can sometimes rent the same mooring three times in one day. And if someone isn’t using their personal mooring, it’s mine. They need to tell me when they’ll be on it, otherwise it’s rented.”

The technology doesn’t stop there. These days all his boats’ engines have onboard computers. Charlie can upload through a USB port in the engine all sorts of info so that he can be certain to replace it when needed. “You don’t want to be on the water when you discover your motor is too old. Plus,” Charlie brightens, “I can tell when my kids have taken the boats out too far or too long.”

Charlie’s kids. These are the dozen or so young adults Charlie hires each year to assist with all the chores. “Ugh,” I can’t help but exclaim, “that must be tough.” To the contrary, Charlie loves it. “The less these kids know, the better when they come to work for me. They haven’t learned how to do things the wrong way yet.” Charlie loves to teach. Charlie loves to see people develop skills needed to be good boatmen. Charlie loves to share what he’s learned. And it’s a lot.

He doesn’t love everything, though. “I hate it when people die.” I nod in agreement, “Yes, that is bad.” But he’s also not terribly fond of the boats from across the way on the Cape that gather on the beach at Chappy’s Gut. “Someone is going to die out there sooner than later. It’s too crowded and people are too drunk.”

Before the coronavirus pandemic, the town had suggested limiting the Gut beach to ten boats on any given day. “But,” as Charlie explains, “who’s going to be the one to tell the eleventh boat from Hyannis that they need to return home? Probably not me.”

But he’ll be there to do just about everything else.

There was a time in my life when I did not sleep – my mind wouldn’t allow my body the rest it so desperately needed. On some of these nights I would stand at the window of our cabin that overlooked Edgartown’s outer harbor and look for a light on the water – some sign that I wasn’t alone. I found comfort in the vast unseen life in a deep-dark unknown; moreover, I felt a kinship in those few of us that were witness to this mystery at that moment. Sometimes it was just the clang of a buoy, or the light across the harbor, but mostly it was a belief that somewhere out there another being was being. And now, I imagine, it may well have been Charlie Blair.