The net burst open and the sea spilled out onto the boat’s deck. A briny collection of ocean critters and bottom feeders flopped and scurried about, adjusting to their new surroundings inside a boarded-off collection area. One small crab scamp-ered out of a crevice, only to be scooped up and dropped back in by a human hand cracked and rough as sandpaper. Dennis (Denny) Jason Jr. surveyed the haul: a pyramid of horseshoe crabs, Irish moss, and a few measly pounds of fluke. He let out a long sigh, audible over the moan of the engine and full of a summer’s worth of frustration. Fluke is his livelihood, but lately they’d been unpredictable in the waters just off Lobsterville Beach.

Jason Jr. set off on this brisk August morning last summer at his usual time of 4:30, his boat cutting through a shroud of fog in hopes of turning his fortunes. After the first hour-long trawl of the Sound bed, there was little to show for it. In the light of dawn, a few other boats appeared nearby, some manned by guys he’s known since elementary school.

“That boat is beautiful,” he murmured, pointing to one farther out at sea. The other boats are faster. Their nets are larger. They aren’t made of wood.

Jason Jr. separated out the good catch from the bad, tossing most back into the water. The fluke was stacked about a foot high in a sixty-pound holding basket. “We’ll probably only get half a basket today. This is the way it’s been all summer,” he said defeatedly. He hosed down what was left and walked across the wooden planks that creaked with each step to the wheelhouse, bathed in a blood-orange light. Grabbing the wooden wheel with both hands, he started turning it clockwise to try his luck dragging in the other direction.

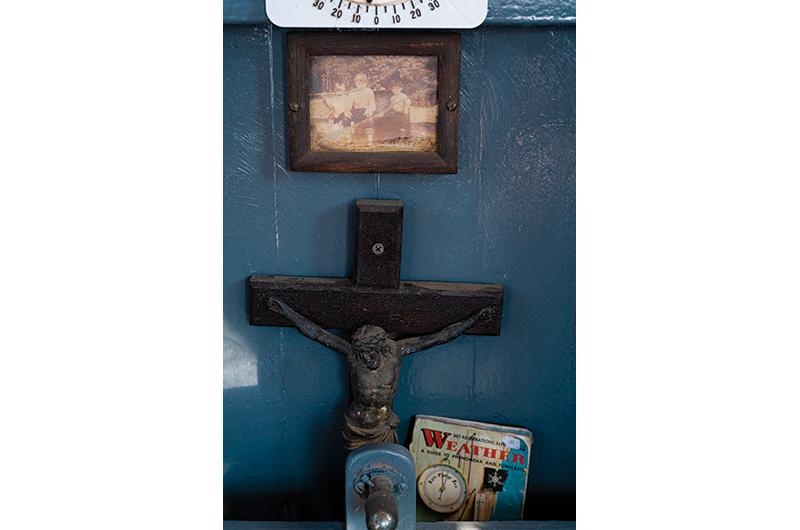

A photo of him with his dad, Dennis (Denny) Jason Sr., the boat’s previous owner, sat on a shelf in front of him along with a tide chart, a stack of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, a Rubik’s Cube he’d been trying to solve all summer, and his grandfather’s crucifix. He isn’t religious, but fishermen are a superstitious lot. “It’s got to be somewhat good luck,” he said with a shrug. He would need all the luck he could get for the long day ahead, holding onto hope every time he opened the net that the fluke would finally show. If they didn’t, he said looking out longingly at his competition, it could spell the end of a near century-long family legacy: the vessel itself, one of the last of its kind with the most iconic mast in Menemsha Harbor, the Little Lady.

Even if you don’t know her by name, if you’ve been to Menemsha you’ve probably seen her. It’s likely the paint job that first caught your eye. The almost thirty-foot-high canary-yellow mast is hard to miss, jutting out from an indigo, copper-red, and bottle-green hull. In Vineyard harbors full of white and brown, the primary colors make the Little Lady a celebrity. A portrait of her painted by Island artist Anne McGhee even hangs in the Los Angeles home of one: singer and actor Barbra Streisand.

The cheery exterior, though, masks the ailments within.

On a bright May morning in 2018, Little Lady rested at a slant in a cradle in Vineyard Haven. As the summer fishing season loomed, symptoms of her old age kept appearing, postponing a launch. First, it was a faulty propeller. Then the transmis-sion blew. Not to mention all of the leaks in the hull. If you looked close enough, it even seemed as though she was weep-ing due to small blisters, or concentrations of fluid in the hull, slowly migrating to the surface.

“She’s crying after sitting out for almost three weeks now. Every day there’s something new,” said Jason Jr. He was the doctor that day, but his scrubs were in as rough a shape as the boat. Red paint stains and holes riddled his gray Little Lady T-shirt, cargo shorts, and formerly white sneakers. A backward-facing cap covered his short, dark brown hair, and his hazel eyes seemed stuck in a perpetual squint from submission to the sun.

Little Lady’s former captain and Jason Jr.’s father, Dennis Jason Sr., handed him a large screw from an empty gelato container and grunted in agreement. Now seventy-three and a former Chilmark harbormaster of nearly twenty years, he shares the same squint as his thirty-four-year-old son, his eyes creased at the sides. He tousled his disheveled white hair, blackened at the roots, and grinned from under his bushy Chevron mustache. “Wooden boats don’t like to be out of the wa-ter. She shrinks up,” he said with a shake of his head, explaining that the hull becomes less watertight when drying.

Father stood off to the side as son drilled the one-inch screw into the leak and sealed it with epoxy. They talked only shop in stunted conversation, Jason Sr. doling out advice, asked for or not. The dragger is his son’s responsibility now, though. She’s his to fix. After serving decades of keeping her afloat and her paint polished, Jason Sr. retired from the fami-ly business that began more than nine decades ago with his father, Leonard Jason Sr. (not to be confused with Leonard Ja-son Jr., the former Edgartown and current Chilmark building inspector and Jason Sr.’s brother).

“There’s two Dennys and two Lennys in our family. We keep it pretty simple,” said Jason Jr., acknowledging how confus-ing this might be for readers.

With a long list of expensive repairs still needed before she could get back on the water, Jason Sr. thought it might be time for the boat to call it quits too. “She’s older now. Let her retire,” he urged his son, who either ignored him or didn’t hear him as he slipped into a pair of white paint coveralls and started sanding the painted wood, although many of the oak planks were already exposed. I walked over to one and put my ear to the plank. A soft groan emanated. I put my hand on it and felt, it seemed, the wood ever so slightly retracting, as if the vessel was inhaling.

“The boat is alive,” Jason Jr. had told me weeks earlier over sandwiches on the 7a Foods porch in West Tisbury. “She’s a living thing because the wood is alive.”

Little Lady was born on the shores of the Mystic River in Connecticut in 1929, though you wouldn’t have recognized her then. Her colorful cosmetic lift came much later. She was just one of the many wooden draggers scouring the coast at the time, hauling in bountiful nets of fresh catch when Leonard Jason Sr., a twenty-two-year-old from the Azores, bought her and brought her to the Vineyard.

It was the 1930s, and trawling was revolutionizing the fishing industry. Like a hand scooping out the last kernels from a popcorn bag, the new diesel-powered boats dragged enormous funnel-shaped nets called otter trawls along the ocean bed. Little Lady is a side dragger, meaning the trawl is attached to the side of the boat instead of the stern. It’s a slow process, but just one hour-long trawl can wrangle in a whole school of fish if you’re lucky.

Before sailing her to Menemsha, Leonard Jason Sr. cut her snub nose off and hired a one-eyed builder named Travis to add extensions to the bow that made her into what Jason Sr. calls the forty-two-foot-long, twenty-seven-ton “big little boat” you see today.

“We used to joke that he had one hell of an eye because this is what came out,” he said.

It was then that she also received her name, though the present Jasons can only hazard a guess as to why their father and grandfather chose Little Lady. “We all used to speculate it was because of my mother,” Jason Sr. said. “She was Hilda. She was cute and a little lady. So we thought that sounds as good as anything. We know she’s a she because of the expense to make her happy.”

It was Leonard Jason Sr. who started painting her yellow as part of her upkeep (the tint is actually called “Little Lady Buff”) and she garnered a reputation, but it wasn’t until she saved a life during Hurricane Carol in 1954 that it became clear she was special. Coming aboard after the storm, Leonard Jason Sr. found a man in the engine room, soaked and freezing. His boat had capsized and he was forced to climb aboard Little Lady to find shelter and ride out the blow.

In the 1970s, Jason Sr. took over and fished her through the mid-2000s, keeping the trawling tradition alive even as the number of draggers along the Massachusetts coast dwindled due to age and neglect. The catch was still plentiful and profit-able in Menemsha, though, and the Jasons considered her family and worth the constant upkeep and fresh coats of paint.

“She’s been a part of the family so long that we invite her to Thanksgiving,” joked Jason Sr.

“She’s my mistress,” added Jason Jr. “My wife knows that I have another lover.”

By the time it was Jason Jr.’s turn at the helm in 2006, wooden draggers were becoming relics of the past. Steel boats were sleeker and faster with motorized equipment that meant more hauls in less time. New quotas to manage fish popula-tions also bit into his earnings, which go more heavily into upkeep than on a steel boat.

“That’s why there’s no wooden fishing boats left. It’s because of the labor,” he explained. Even with eight- to ten-hour fishing days five days a week from June through September, he said, the money dries out quick when she’s sitting on shore out in the sun. Back in her heyday she could catch up to 1,500 pounds of fish in her net. Now, she’s limited to 300 pounds of fish a day if Jason Jr. can find them. “It’s not sustainable,” he said. “She’s paid for herself over what Lenny spent a thou-sand times over, but she’s a lot to keep up and pay for.”

Jason Jr. knew since middle school that he loved being out on the water and catching fish. He passed on college and, af-ter graduating from the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School and traveling through Europe, returned to Menemsha to work under his dad in 2004 until it was his turn to captain Little Lady two years later. It was inevitable, really, even though Jason Sr. actually told him it was no way to make a living.

“I’m just doing it because I grew up doing it,” he said. Besides, it was (probably) named after his grandmother. It’s his grandfather and father’s legacy. Now it’s his, and he’s going to keep it alive, dammit. Through all the headaches and heartaches his mistress gives him, Jason Jr. won’t let go. How can he? In the best of times, she’s dragged for briny riches. In the worst, she’s kept him alive.

Back in September 2015, he and Little Lady were sailing on choppy waters toward New Bedford when rough weather hit. Caught in heavy winds as he passed through Quick’s Hole, they became stuck in a furious tide that tossed and turned the boat relentlessly. For an old wooden dragger, the threat of planks popping loose and water flooding the boat was as high as the waves. She had made it through hurricanes, though. A squall wasn’t going to bring her down.

“I was nervous. I was like, ‘Holy shit, this isn’t good,’” he recounted. “I told her: ‘Yeah, I’m dumb and young, just get me to calmer waters.’ She heard me. We were stuck in the rip for an hour, but she held on somehow.”

On the 7a porch three years later, he paused and looked off. There had been far more bad times than good since that storm. He was hoping for six to eight more years with her, but the future looked uncertain as she languished on shore at the height of his fishing season. As it turned out, she wouldn’t make it back to the water that year.

Even so, he didn’t leave her. This past summer, she made her quiet return to Menemsha Harbor and greeted visitors at the annual Meet the Fleet event, though without a shiny new coat of paint. The only wooden side dragger still operating in New England wasn’t finished yet.

As the crimson orb of the morning sun peaked out over the Gay Head Cliffs, Jason Jr.’s luck appeared to finally be turning. After an hour and fifteen minutes of dragging against the tide, he started pulling levers and spinning cranks, conducting a cacophony of squeaks and creaks. The huge net loomed over the deck. Jason Jr. tore open its mouth. This time, a whole extended family of fluke streamed out and a rare smile crept onto his face.

“There’s nothing better than catching when you’re fishing,” he said with a sigh of relief. It wasn’t much compared to past years, but it would certainly do. And as luck would have it, it would portend a change in fortune. In a few months’ time he would hit a stretch of good fishing and reach his annual quota.

At that moment, though, that future remained unknown. Jason Jr. took the day’s bounty in cautiously optimistic stride, picking out the fluke from the detritus and packing them in large coolers of ice to be sold at Larsen’s Fish Market on the Menemsha docks.

There had been talk of making the 2019 season Little Lady’s last and sending her back to her hometown to rest in peace in the Mystic Seaport Museum among old friends, but the strong finish last year helped convince Jason Jr. to fish again this year. He likes the idea of sending her to Mystic or another museum when that time does come. In a museum, she can be preserved and enjoyed by future generations. The best part? Someone else will have to plug the leaks.

Letting her go won’t stop him from fishing, though. He said he’s been shopping around for a new, non-wooden boat.

“I love her,” he said sincerely. “When you see her in person, you understand. She casts a spell on you. Realistically, though, I can’t do it forever. She’s kind of holding me back.”

She’s probably not going to make it to her centennial in 2028. You can hear it in the wail of the old engine. You can see it in the holes in the planks. It’s like she’s gasping for air. Still, she endures, with Jason Jr. at the helm each morning, dark and early, her yellow mast disappearing slowly into the fog, the unknown, the future.

“We’re just here,” he said as he turned the bow back toward the harbor. “We’re never going to out push anybody. We just need to get what we can get. It’s stressful. There’s potential for catastrophic failure. It’s a hard life, but we see every sun-rise, and we’ve seen a lot of good sunrises.”

3 comments

3 comments

Comments (3)