Call him Ishmael. Skip Finley’s story, like any great whaling yarn, is about obsession. He embarked on this voyage six years ago, fixated on a passion to tell a tale never before told, at least not in detail, of a history that loomed beneath the ocean of information chronicling the whaling industry.

ocean of information chronicling the whaling industry.

On the final leg of this journey, he may as well have been holding a harpoon as he boarded the Chappy Ferry. He had already made two unsuccessful strikes at finding the William A. Martin House, the only home owned by a black whaling

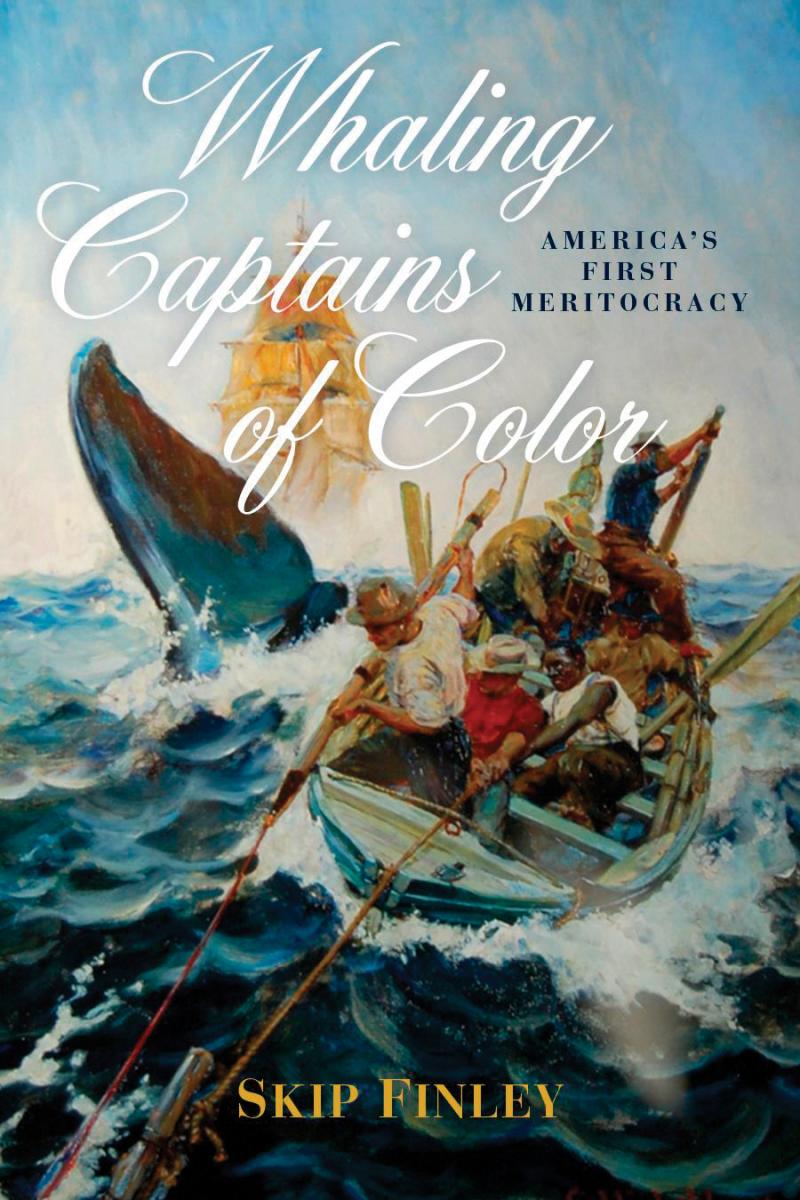

captain still standing roughly in its original form in the United States today. If Finley could find it, it would offer him the last physical, almost living trace of the men he had spent years meticulously researching in his book, Whaling Captains of Color: America’s First Meritocracy, which is just out from the Naval Institute Press.

Peering out from the helm of his white Cadillac, he eyed the channel waters through a windshield speckled by sea spray. This time he was returning with a vengeance, following his intuition and one solid lead: the house would be recognizable based on its condition, he had been told, specifically the sagging roof line thatched with a light blue tarp.

Fitting into the rearview mirror was Edgartown village and its nineteenth-century federalist houses protruding from a bleak winter landscape. The white clapboard homes stood as a reminder of the wealth and power of the great whaling captains of the era, their stories mostly well documented and preserved. But as the car made its way from the ferry onto the Chappaquiddick shore, the view of the village faded into the distance and Finley revealed what drove him to the point of obsession in the first place.

The whaling industry dominated the economy of the Vineyard and the rest of southeast New England for more than 150 years, he explained. It ranked among the largest American industries of the mid-nineteenth century, rivaled only by the likes of cotton, agriculture, and the slave trade. Its main product – oil – lit candles during the Revolutionary War, cured leather in the heartland, and lubricated the machines that heaved the county through the Industrial Revolution. The industry made New England seaports such as New Bedford, Edgartown, and Provincetown the Middle East of their day – the wealth pumped into these harbors still quantifiable by the prodigious manors that line their old town centers.

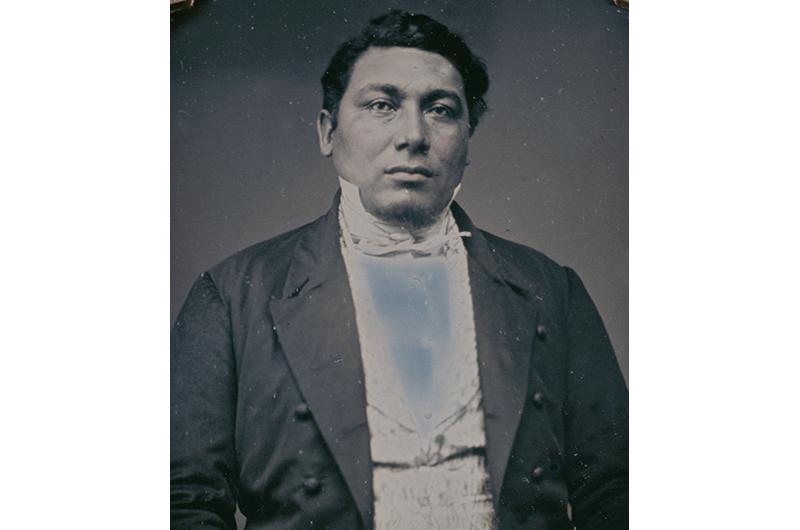

The prospect of immeasurable wealth lured roughly 175,000 men and the occasional woman to sea on some 2,700 different ships captained by 2,500 different masters, bracing the oceans on some 16,000 voyages. Portraits of many of those captains still hang on the walls of New England’s museums and libraries. In a typical one, he is a man wearing a black waistcoat with frilled collars, perhaps with a ship in the background. The only other thing that differentiates him from tycoons of other industries, steel or petroleum, is his sea-weathered face often strapped with a pair of white muttonchops. It is a portrait that sits proudly on the mantle of America’s national psyche, staring back at us from the annals of history, from an era in which opportunity was defined by race. He is, of course, white.

At least, that is the portrait Finley had in mind before he set foot inside the New Bedford Whaling Museum on assignment to write a profile for this magazine of Captain William A. Martin, the great-grandson of a slave brought from Guinea to Chilmark in the eighteenth century.

“I said, ‘Wait a minute, this was around 1880. That’s fifteen years after the Civil War. How did this man get to the rank of captain?’ I went nuts with just that one thought and let it run,” Finley said from the driver’s seat. “Before I knew it, I had so much information on Captain Martin, on just this one guy, I knew there had to be more.”

The profile of Captain Martin sent Finley in pursuit of this hidden history. He ordered more than one hundred whaling books, researched thousands of websites, and started talking to the foremost scholars of the whaling era. At each turn he found the stories he was searching for submerged beneath the swell of documented history, often referenced only in the footnotes of books that paid homage to the white captains who made up the majority of the industry.

But when he found the Seamen’s Protection Certificates – “gold,” as he called it – you could almost hear him cry out from across the vacant genealogical room of the New Bedford Public Library: “Thar blows!”, the ancient call that a whale has been spotted.

The certificates were drafted by customs officers documenting the name, age, rank, hair, and skin color of crews passing through various ports from the end of the eighteenth century to the brink of the twentieth century – the heyday of the whaling era. The records might have been lost but for the efforts of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration’s Historical Records Survey. At least one anonymous worker transcribed a portion of the certificates onto index cards and filed them at the New Bedford Public Library. The National Archives Catalog also maintains an online index of these certificates. But the rest, once held locally in Nantucket and Long Island, are thought to have been lost in fires.

Finley began poring through the 131,000 index cards by hand, forging friendships with the night-shift librarians. He pulled the cards that listed the men as tan, brown, black, or mulatto, offering little more than a sketch of an identity, and matched them with scattered newspaper clippings and footnotes from larger bodies of work. The process took weeks. Weeks, that is, before the director of the library found Finley hunched over a copy machine late one night and informed him that the index cards had already been digitized on a spreadsheet – 131,000 lines long and seventeen columns wide.

Finley, whose day job is the director of sales and marketing for the Vineyard Gazette Media Group, which publishes this magazine, loves few things in the world more than a spreadsheet.

“I data sorted the shit out of it,” he said. “I sorted by captain and by race. All of a sudden people were jumping off the page and I had a starting point. Now I had names. And from there I could figure out, through books and journals and newspaper clippings, who these guys were.”

Until recently, Finley never considered himself a writer. He built his career in radio and television, cutting his teeth as a floor director for WHDH-TV in Boston in 1971 and in the sales department for Boston’s WRKO-AM. For ten years he traversed the waves of the radio industry, working his way to the captain’s quarters as president of Sheridan Broadcasting Networks. In 1982, he founded Albimar Communications, through which he owned and managed the popular black radio station WKYS-FM based out of Washington, D.C. By 1988 he had invested his way into two more radio conglomerates – Carter Broadcast Group Inc., the nation’s oldest black-owned radio station company, and American Urban Radio Networks, where he launched The Light, a twenty-four-hour syndicated black gospel radio station.

“You’ve heard of Howard Stern?” he said. “Well, the guys on these networks were the black ones.” Which is not to say his networks catered exclusively to a black audience. The first radio station he owned was a rock station in Omaha, Nebraska. And later in his career he directed the purchase of an AM news station on which Rush Limbaugh rode point.

“It was only money, man. It was just another radio station,” he said. “I had the number one, two, and three stations and they were black. I got to play both sides of the advertising market, accrete 100 percent to that revenue and make it into cash flow.

I was a suit. That’s what I was good at.”

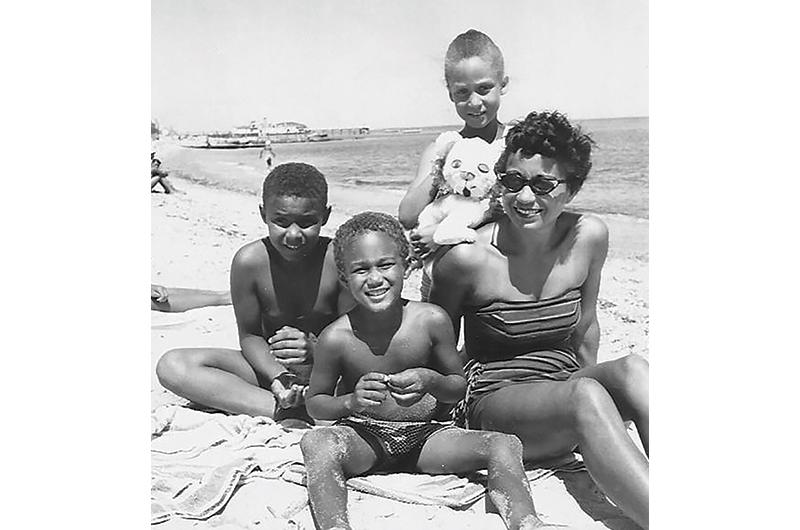

But long before his days as a titan of the radio industry, he was a student at Northeastern University in Boston. And long before that he was a kid from Rockville Centre, New York. His father started one of the largest black-owned engineering firms in the country, working on massive projects such as the Throgs Neck Bridge and the Harlem State Office Building.

And yet when Finley went to Northeastern to study drama, by his own account he did anything but study. He fought on the front lines of the civil rights movement but severed his ties to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee when, confronted with the violence of racism, he found it hard to remain peaceful. He worked as a professional go-go dancer in the legendary Boston nightclub The Boston Tea Party at Berkeley Street. He opened an art gallery on Newbury Street during his junior year, which went under by his senior year.

And five weeks before his graduation, he dropped out to start his first job at WHDH-TV. Along the way he also met, fell in love with, and married Karen Michele Woolard, now his wife of forty-nine years.

He didn’t begin writing until after what he calls his fifth failed attempt at retirement. In 1999 he and Karen moved full time to Martha’s Vineyard, where he had summered with his family since the age of six. He turned to writing as a hobby and started a newsletter circulated among friends called the Vineyard Vine. That eventually gave way to him writing the Oak Bluffs town column for the Vineyard Gazette, which subsequently hired him to run the advertising and marketing department. From there his columns inspired his first historical novel – and then his second.

“I didn’t get here because I was cute, because I was cool, and definitely not because I’m black,” he said of his various successes in life. “I got here because I could do the job. And that’s what the book is about. It’s about these guys who could do the job and were damn good at it long before anyone thought they had a chance of doing anything at all.”

But he quickly deflects any further comparison to the whaling captains of color. “Writing,” he said, “it’s something that keeps me from going crazy and making wampum necklaces for a living. I’m not like those guys. Nothing I’ve ever done was stinky and hard. And it certainly was never going to kill me.”

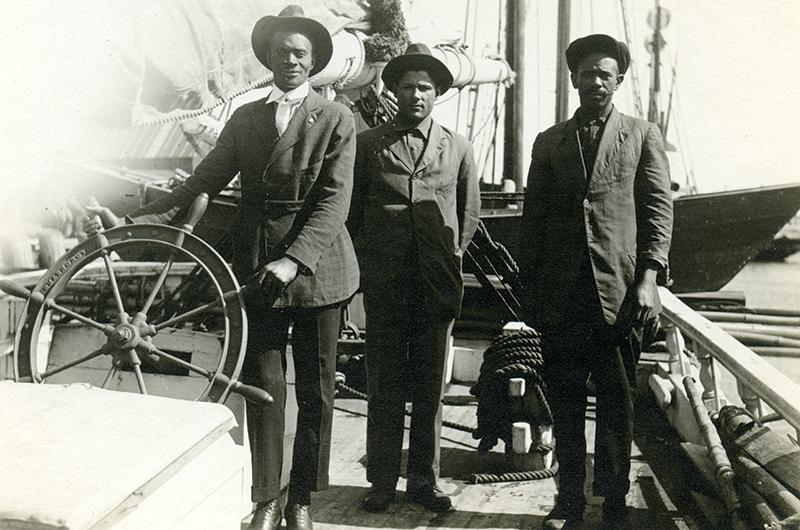

Over the course of several years of research, Finley discovered that there were at least fifty-two whaling captains of color, a term he uses in his book to hedge the racial ambiguities due to a lack of documentation, and because the men – Native American, the progeny of African slaves, or Cape Verdean immigrants – were often of mixed heritage. Adding those who did not rise to the rank of captain, he estimates that 20 to 30 percent of all the people who went to sea on whaling ships were men of color.

From the mountains of yellowing clips and stacks of archives, a narrative of these previously one-dimensional figures emerged, first only as a nervous boil on the surface, then ultimately breaching as a leviathan. He discovered their family origins, their religions, their ships, their crews, where their expeditions had taken them, and the problems they had faced. He learned of their triumphs and their failures. And through a handful of journals, he learned of their vices at sea and what made them proud to return to port. Gradually, that iconic portrait of the quintessential whaling captain, the one with the muttonchops and frilled collars, panned out into an ethnically diverse tableau that revealed the history of the people from all walks who played a role in the whaling era.

“It was all little pieces of a greater puzzle spread out over the 110 miles between here and Provincetown,” he said. “The closest thing I got to whole stories were scrapbooks. People would collect articles about their whaling captain father. I had those and I had the names. But they almost never said the guys were black or Native American. Maybe an allusion to color or, at best, a photograph. I don’t know why; I can only guess that it wasn’t worthy of knowing.”

As Finley writes in his book, the pursuit of wealth and adventure wasn’t the only reason men went to sea. Often they faced troubles on land hairy enough to make the ocean voyage – with its vermin-infested food, grueling hours, filthy conditions, utter boredom, and constant fear of death – seem the better option. The typical cast of characters on a ship ranged from naive young boys to what one log described as “unmoral and unprincipled wretches” who “attempted to elude the Ten Commandments....confirmed drunkards, vagrant ne’er-do-wells, unapprehended criminals, escaped convicts and dissipated and diseased human derelicts of every description.”

White crew members, particularly those with criminal backgrounds or mental illnesses, were often driven to climb aboard a whale ship at the lowest rank to escape their pasts.

But for men of color who faced slavery, lynchings, discrimination, and a blatant lack of opportunity on land, their drive was to escape the realities of everyday life on American soil. A whaling vessel, which offered opportunities to all men

regardless of their skin color or checkered pasts, was a clear path to the American dream that never existed for all on land.

Not that racism disappeared at the dock. Many ship owners believed that men of color were accustomed to subservience under slavery and therefore made better crewmen, not to mention that they made do with less pay than their white counterparts. Still, at the end of each long day, tired and sore, these men from all walks would curl up on coffin-sized bunks made of straw or cornhusks in a space no larger than an average sized chicken coop. “Men learned to get along because there was nowhere else to go,” Finley believes. “Racial prejudice had no place there. Men were judged not by the color of their skin but by their ability.”

The stark differences in opportunity on land also played a role in the ascent of the captains of color, who rose to command a crew of white sailors they could order flogged while at sea but couldn’t look in the eye on soil. Ninety percent of men who went whaling went out only once, Finley estimates. For greenhands – as those on their first voyage were called due to the color of their flesh before they gained their sea legs – it often only took a few hours aboard the vessel to realize they had made a mistake.

So the majority of those lucky enough to return to port three-and-a-half years later, especially if they had earned a foothold of wealth, decided that one voyage was plenty.

If they were white, that is. Sailors of color didn’t have the same opportunities to work on land. Whaling may have been, as Finley quotes the curator of the Sag Harbor Whaling & Historical Museum, Richard Doctorow, a “cross between working in an oil refinery and slaughterhouse, with the chance of drowning thrown in.” But for sailors of color it was the lesser of two evils, and they ventured out on countless voyages, gaining valuable skill and experience. In the not-uncommon event that a ship suddenly found itself at sea without a captain, it only made sense that these men, the ones trusted the most to guide the ship home, would be promoted.

“These guys are 1,200 miles offshore. The captain just died, committed suicide, or is sick. Who is going to get us home? That is the person with the most experience,” Finley explained. “These people of color, who had been on ship after ship after ship.”

Such was the case for Captain William A. Martin, who enlisted on his first trip as a greenhand in 1846, launching off from Edgartown. He earned $189.70 for the first twenty-nine-month voyage and would set out on another fourteen voyages over the next thirty-two years, climbing the ranks to officer and finally to captain. His last voyage, in 1890, ended poorly when after nearly three years at sea in seemingly endless storms and mishaps, he fell ill and resigned his command. Following the voyage, he retired to his modest Chappaquiddick home to live out the rest of his days as a paralytic in solitude with his wife, Sarah.

The winding Chappaquiddick dirt roads led down many wrong paths in pursuit of the captain’s house. On one wrong turn Finley found himself bounding down the snow-covered road that cuts behind Slip Away Farm. The Martin house wasn’t there, but Collins Heavener, a farmer and wooden-furniture maker, stood in front of the farmhouse cradling a dog named Sunday in his arms.

“Oh, the Captain Martin House,” he said, smoothing his dog’s coat with one hand and pointing with the other. “Take a left out of the driveway and head about a mile down the road, past the store until you hit Jeffers Lane, and I believe it’s directly across from that.

“It’s in fairly rough shape. The folks have been trying to figure out what to do with it. But you should be able to find it, the tarp is a pretty distinguishing factor.”

It was. From behind a thicket of pitch pine and scrub oak, the house stood stoic in an afternoon glow. Its wind-gnawed shingles looked like sets of gnarled teeth and its cracked sills gave the impression of a proudly wrinkled face. The house had almost fallen into itself, hunched over a crumbling foundation of hand-cast brick.

Finley made his way down the unplowed driveway, past a dinghy with its motor slumped into the snow. He cupped his hands over a window and peered in, his eyes landing on the hearth Captain Martin had likely warmed himself beside after returning from a long voyage. He pulled back, his eyes falling on the door, then the face of the house, then the stand of trees that framed it. And past that a long sky that led out to the ocean, where this voyage began.

“It tells the whole story without any words,” he said.

10 comments

10 comments

Comments (10)