Gus Ben David deals with a lot of people calling him about wildlife. Over the years he’s become the unofficial conduit through which animal reports from Island residents proceed to the state wildlife agencies. “I’m always called,” he said. “Anytime an animal’s seen on Martha’s Vineyard...that’s the way it is. Cut and dry.”

He’s a check on what MassWildlife biologist Dave Wattles calls the public’s “varying ability to correctly identify animals.” Ben David is less politic: “I had one guy, oh my God what an obnoxious bastard, said he’s from Montana or Wyoming. From cougar country. And he called up and said he saw a cougar. I said, ‘You saw a cougar, huh?’ And he said, ‘I come from Wyoming! I know! I live with ’em!’ Okay. He didn’t see a cougar.”

In other words, Ben David doesn’t believe it until he sees it. “In science, you know, you have to have confirmation,” he said in his cabin near the Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary in Edgartown, where he served as director for thirty-six years. The shelves around us were full of the books and animal bits collected through a lifetime of Island naturalism. He shook his head, “People see things all the time, but it’s never recorded. Most people don’t know their license plate number. Human behavior.”

Last May, Ben David received a call about a creature captured by a security camera on a South Shore estate. The creature was about the size of a German shepherd with pointy ears and a pointy nose and a big bushy tail held parallel to the ground. It had a grayish coat and a loping, shuffling gait. It definitely wasn’t a dog. It definitely wasn’t a cougar. And it definitely wasn’t supposed to be on Martha’s Vineyard.

“The caretaker, who has many surveillance cameras, downloaded this thing in the morning,” said Ben David, “and he says, ‘Oh my God, I think I got a coyote!’ And he called me right up and I said, ‘Yeah. You do.’” Later in the season the same, or another, coyote turned up on security cameras in Katama. In January of this year, a coyote that looked to be about fifty pounds was caught on video by a trail camera in Oak Bluffs, not far from the Goodale Construction Co. gravel pit.

The recent spate of coyotes were not the first to be sighted here, dead or alive. In 2011, a trail camera captured one loitering around the beach on the North Shore. (A call was made. A photo was sent. “It was a live coyote,” Ben David confirmed.) In 2010, a suspicious pile of scat from Seven Gates Farm in Chilmark was sent to be analyzed at a lab in California. The results came back consistent with coyote DNA (although that, as I’ll explain later on, is kind of complicated). The next year, a man reported he had heard a coyote yipping near his West Tisbury property, which inspired a meeting of concerned farmers who floated the idea of “early eradication” as the only chance of preventing a breeding population from being established. In addition to these encounters with live coyotes, Ben David has personally examined five dead ones found on the North Shore since 2004. The Vineyard Gazette reported another sighting back in 1998, though it remained unconfirmed.

But beyond those few images and bodies washed ashore, no data exists about coyotes on Martha’s Vineyard, how they have made it here, or are likely to come here in the future. Likewise, it remains unclear what the long- and short-term impacts of an established population of this top predator might be.

“People come to me and ask,” griped Ben David, “‘Well, Gus, what’s gonna happen if they get to the Vineyard? How’s it gonna affect the ecology? Is it gonna do this? Is it gonna do that?’” He can guess, but he doesn’t know. Nor, truth be told, does anyone else. It’s not idle speculation, however. From up close, a live coyote on Martha’s Vineyard is just a curiosity, or perhaps a concern, depending on your temperament and livelihood. But from a historical perspective, the arrival of coyotes on Martha’s Vineyard is a culmination of a century of range expansion for the species, an expansion that, as wild and “natural” as it may seem, is largely an unintended outcome of human-driven changes to the North American continent.

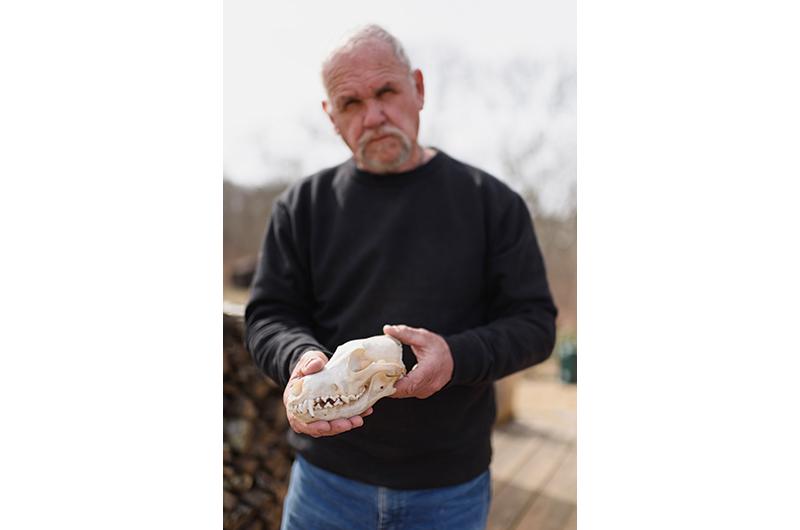

Ben David handed me a skull. “This is a coyote skull. And they’re a formidable animal,” he said, emphasizing “formidable” with evident respect. Coyote. Canis latrans. Latin for “barking dog” or, as Ben David says, “bahking dahg.” He found the skull on one of the Elizabeth Islands, the archipelago of barely developed islands that runs from Woods Hole to Cuttyhunk, dividing Vineyard Sound from Buzzards Bay.

It was candle-wax white and weighed less than it looked, like pumice rock. Ben David pointed out the indicative elongate canines and the sagittal crest along the top of the skull, which implies powerful jaw muscles. It was easy to imagine this mouth making mincemeat of an unlucky mouse or an overfed cat. Ben David considered the skull as I held it out poor-Yorick style.

“He’s an enigma in some ways,” he said.

There is fossil evidence that suggests coyotes or coyote-like animals roamed Northeastern North America during the Pleistocene era, which ended roughly 12,000 years ago, when sea levels were far lower than they are today due to the water locked up in the glaciers of the most recent ice age. Martha’s Vineyard wasn’t an island then, so it’s reasonable to assume that coyotes at least passed through the low hills and sandy outwash plains of the area, as did wolves, though there is no direct evidence at this point that either species lived on the Vineyard after it was cut off from the mainland by rising seas. There were, however, foxes, skunks, raccoons, bobcats, and black bears on the Island.

By the early nineteenth century, all of these mammalian predators were gone, having been killed by human residents either directly or indirectly through loss of habitat. With help from humans, some, such as skunk and raccoon, have returned with a vengeance. Foxes at one point were also on the rebound. In 1881, “Governor” Crosstown Cary, a member of the New York Stock Exchange and a Martha’s Vineyard booster, decided to host a fox hunt in Katama, only to learn there were no more foxes on the Island to hunt. Undeterred, he arranged for a small group of red foxes, Vulpes vulpes, to be brought from the mainland, and one fine morning in August he and his friends turned out for the festivities. The foxes were released and the hunt commenced. By sunset, however, Cary and his friends only bagged a single fox. Evidently, they were out of practice.

The escaped foxes made a home on the Island and multiplied. Soon, they lived in sufficient numbers to become “a positive menace to poultry and sheep.” Island residents petitioned in Boston to create a bounty on the foxes, and by 1890 “everyone who could handle a gun” was contributing to the extermination effort, in particular one George Whitten Manter, who personally eliminated hundreds of foxes by studying their behavior and feeding habits. By 1905, V. vulpes was once again extinct on the Island.

Around the time Cary was releasing his foxes on the Island, coyotes were in the early stages of expanding their own range from the Southwest and Great Plains to east of the Mississippi. Notwithstanding the prehistoric presence of the occasional coyote in the region, the vast forest that stretched east from the Mississippi in the pre-Columbian period was primarily wolf and mountain lion country in which coyotes were occasional, outmatched interlopers.

But as the ecosystems east of the Mississippi were transformed by the westward expansion of the United States, the coyote’s history reads like a kind of inverse manifest destiny: settlers moving west decimated wolf and puma populations, giving coyotes new territorial opportunities free from competition with those larger predators. As the eastern forests were replaced with farms and fences, the smaller dogs gained a habitat abundant with small prey animals and human subsidies in the form of livestock.

By the early 1900s coyotes were in Michigan and western Ontario. There were reports of them in New York in the 1920s and then in the rest of New England through the ’30s and ’40s, although they weren’t yet common. By the 1990s, coyotes could be found abundantly in most of eastern North America, including isolated areas such as Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, and even Manhattan. In 1985, an officer on Otis Air Force Base made the first coyote sighting on Cape Cod. By 1986, they had spread throughout the Cape and onto the Elizabeth Islands, both by swimming and crossing on ice. From Naushon, one of the Elizabeth Islands, the Vineyard is a four-mile doggy paddle across the Sound.

This remarkable expansion of territory did not go unnoticed by the humans whose “settling” had set it in motion. As the amount of livestock being raised in the west increased, efforts to stymie the burgeoning coyote population also increased. These extermination efforts involved mass poisoning and gunning, sometimes from airplanes and helicopters. Strychnine, a widely available poison that causes death by destroying a coyote’s central nervous system, was

a key weapon against coyotes until the Environmental Protection Agency restricted its use in the 1980s.

In 1924 alone, more than two million poisoned bait stations were placed across the west. According to historian Dan Flores, the author of Coyote America: A Natural and Supernatural History (Basic Books, 2016), 1.8 million coyotes were killed between 1915 and 1947. Another three million, and possibly as many as six million, were killed between 1945 and 1971. Since that era, coyote management policies have de-emphasized lethal controls, though an estimated 500,000 coyotes are still killed every year in the United States, and coyote-hunting competitions remain widespread.

The move away from lethal control efforts was due less to a newfound ethical concern than to the realization by wildlife managers that the extermination campaign waged against coyotes for decades actually had the ironic effect of increasing the rate of range expansion in all directions. What the folks charged with eradicating the coyotes didn’t understand was that coyote litter size responds to population density. So, like slicing off a hydra-head, killing an adult coyote meant more coyote pups would be born, spawning more transients and therefore more expansion and so on. Over and over coyote hunters were frustrated by how an area cleared of coyotes would immediately be colonized by transients from elsewhere and undo all their good work.

Coyotes are particularly good dispersers because of their generalist diet and adaptability. “They can live on vegetation, insects, anything,” said Ben David. “There isn’t anything that thing won’t eat. Nothing. Carrion. Dead stuff. Whale carcasses.” They’re good at making do, particularly around human populations. “For the fifteen thousand years since we humans have been in North America, coyotes have always been capable of living among us…. A coyote’s primary prey happens to be…the mice and rats that flourish around and among us,” wrote Flores. Like crows, raccoons, and rats, coyotes are synanthropes, or urban adapters. They like us. Even if we don’t always return the favor.

The animal’s complex social structure also encourages dispersal into new territory. In an average pack, there’s a breeding pair (the alphas), a few “helper” coyotes (the betas), and then the pups, who on average come in litters of five. From each annual litter, typically one or two pups stick around to form a pack with their parents while the rest run away from home in adolescence when conflict with their parents – the alpha pair – reaches a breaking point. These juvenile coyotes become transients, nomads, dispersers, who can travel hundreds of miles in search of food, a mate, and unoccupied territory. What a mammal wants.

“Dispersing coyotes seem to move about like bumper cars,” wrote coyote biologist Marc Bekoff, “‘bouncing off’ of other individuals and different places until they settle down.” The coyotes that have come across Vineyard Sound were likely transients who bounced around the coyote-saturated Elizabeth Islands before ending up in the water.

Like everyone else I spoke to, biologist Jonathan Way, who has a doctorate in the study of eastern coyotes/coywolves and has spent the last twenty years tracking and studying coyotes in Massachusetts, thinks the coyotes that have come to Martha’s Vineyard swam here from the Elizabeth Islands. Coyotes colonized Newfoundland, which is separated from the mainland by almost ten miles of ocean (although they had help from the ice floes). Coyotes swam out to Fisher Island, two miles off the coast of Connecticut. Through a combination of swimming and crossing bridges, coyotes established themselves on Conanicut and Aquidneck islands in nearby Narraganset Bay, where the Narraganset Bay Coyote Study has tracked their steady success since. “I’m surprised there isn’t already an established population,” Way told me. “They’re some of the world’s best dispersers.”

All this is to say that the coyotes that have recently arrived on the Vineyard have, from a multigenerational perspective, had a long trip. In their genome, they carry a lasting mark of their ancestor’s epic journey: over the decades, many dispersing coyotes mated with eastern wolves and gray wolves along the front lines of their expansion. These wolves, unable to easily find members of their own decimated populations, made do with C. latrans. The resultant genetic mixing – called introgression – spread through the coyote population in the east.

The offspring produced by this interspecific ménage à trois is the subspecies called the eastern coyote, or coywolf, depending who you ask. Canis latrans var. The eastern coyote is on average larger – thirty to forty-five pounds – and often redder than its western counterparts. “I’ve seen them over on Naushon and honest to God they’re almost orange,” said Ben David. The largest one he’s heard of on the Elizabeth Islands was fifty-seven pounds. There is also evidence that on the edge of the expanding range, where there were fewer coyotes and no wolves, coyotes mated with dogs. “There’s such a hodgepodge of genetics in them,” said Ben David. “It’s a taxonomist’s dream.” Or nightmare, depending.

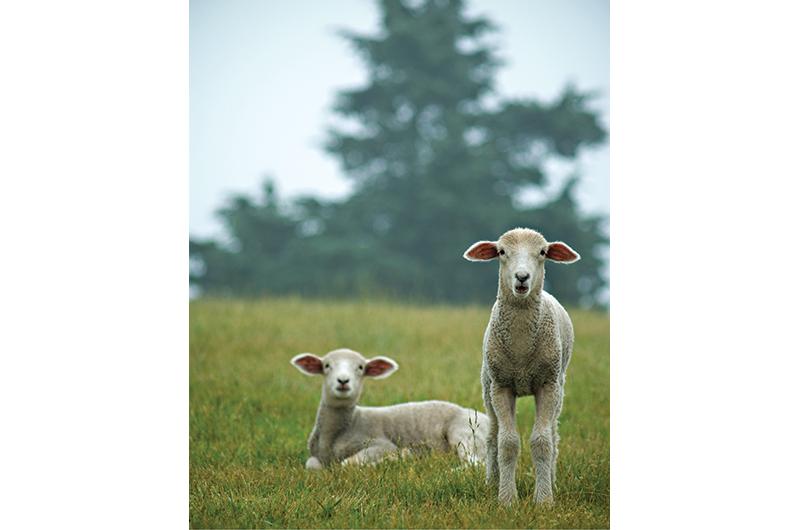

Allen Healy of Mermaid Farm in Chilmark estimates there are 300 to 400 sheep ranging on Martha’s Vineyard. Most of these range freely, though Healy has his own method of “intensive planned grazing,” or mob grazing, which is meant to mimic the way buffalo congregated on the Great Plains. The “mob” refers to the way the herd will gather together in the presence of a predator. “With an electric fence I create a predator which keeps them mobbed up,” he explained. Now, with a real predator around and maybe more to come, Healy wasn’t too concerned.

“I think I might welcome it,” he said. A population of coyotes might help control the turkey and deer populations that eat his flock’s forage every night, he reasoned. He’d get himself a guard dog. “I’m kind of in a dream world to think predators won’t make it here,” he said.

Healy’s equanimity may be noble, but in other places in the Northeast where coyotes have appeared there has been an impact on livestock. In 1986, the first year coyotes appeared on the Elizabeth Islands, Naushon Farms reported thirty sheep taken by what might have been just a single coyote pair. After getting a guard dog and rounding up their sheep each night, the farm reported no killings for the next two years, but the bucolic days of large free-ranging herds on Naushon were over for good. Nationally, the American Sheep Industry Association reported in 2014 that about one-fifth of total livestock losses were due to coyote depredation. (There have been only twelve coyote-human incidents in the history of coyotes in Massachusetts, making them roughly as rare as human-shark incidents.)

Clarissa Allen of The Allen Farm, who has about 140 free-ranging sheep, is much more concerned than Healy about the prospect of coyotes becoming established on the Island. “It would be terrible,” she said. “We won’t have the Allen Farm as a sheep farm in Chilmark. It won’t be able to survive.” I told her I’d heard guard dogs are effective deterrents against coyotes and that seemed to cheer her up a bit. “I guess I’ll need to get myself a Great Pyrenees,” she said.

On the Vineyard, an established population of coyotes would probably cause some livestock losses and almost certainly complicate life for free-range sheep and poultry farmers. Still, it’s wrong to imagine hordes of coyotes slathering over helpless lambkins. “If [coyotes] preferred domestic animals there would be way more depredation,” noted biologist Way. Having such abundant sources of wild prey, Vineyard coyotes might not even go after livestock at all, especially if they’re not allowed to develop a taste for domestic animals early in their tenure here as they did on Naushon. And farmers are not without methods to deter coyotes from preying on their animals. In addition to the aforementioned guard dogs, there’s good fences and methods of “taste aversion.”

What’s not effective, as ranchers in the west learned the hard way, is killing coyotes in an established population. Farmers can apply for out-of-season permits to kill coyotes hunting their livestock, but without a sustained and substantial eradication effort – MassWildlife biologist Wattles cited an estimate that it would take a 70 percent population reduction several years in a row to have any lasting effect in a region – controlling coyotes through killing is a lost cause. “The reality is, once you do get them in a habitat, you’re not gonna get rid of them,” said Ben David.

But all this might be jumping the gun, so to speak. Not all informed observers are convinced coyotes are an inevitable part of the Island’s future. The first confirmed image of a live coyote on the Island was captured in 2011 on a wildlife camera that biologist Liz Olson of BiodiversityWorks had set up to spy on river otters on the North Shore. That was nine years ago and neither Olson nor BiodiversityWorks founder and director Luanne Johnson has seen any evidence of an established population. Both said it’s impossible to know whether the recent sightings are of a single animal. It could be the “same coyote trying to find a friend,” said Olson. “Traveling the whole Island looking for a friend.”

“A coyote would have to get here first, and they don’t get here very frequently,” said Johnson when asked about the likelihood of a population becoming established here. “And then it’s only one. And then it has to have another one to breed with. And then somebody has to not shoot them and kill them. And with the low tolerance from the community here on the Island, I just don’t think they’re going to last very long before people are going to get rid of them, even though it may not be legal to do so at the time of year they’re doing it. People are still going to do it because it’s Martha’s Vineyard. People run by their own rules here.” (In Massachusetts, which has the strictest coyote-hunting regulations in the country, it’s legal to hunt coyotes from late October through early March.)

But what if, despite all obstacles, coyotes do become established on Martha’s Vineyard, I asked Johnson. “I think they would definitely alter some of the skunk and the raccoon activity and behaviors,” she said after emphasizing there is no real way to know. “Coyotes eat a lot of rodents. So that might help us with Lyme disease. They eat a lot of rabbits. Could help with tularemia.” Other than a few fawns and weak individuals in winter, she does not believe coyotes would have much impact on the deer population, but she noted that in Chicago coyotes have significantly reduced the population of Canada geese.

Smaller birds, on the other hand, might benefit. “You have coyotes around, people might not let their cats outside free roaming,” she added. “That would make me pretty happy. It would make all the small wildlife on the Island really happy.”

That’s one version. Someone else, also with evidence, could argue that these big eastern coyotes will impact the deer population, totally ignore raccoons, have no effect on Lyme, decimate the turkeys, and develop a real taste for thrown-out Back Door Donuts.

What seems certain is that a breeding pair would quickly colonize the whole Island. Based on his experience in Barnstable, Way estimates that this Island could support forty to fifty animals. “There’s plenty of habitat for probably ten packs,” he said. They would have little trouble finding food and habitat for dens and would thrive in the Vineyard’s combination of forested, suburban, and rural landscapes. A population established by a single breeding pair might suffer from inbreeding, but the arrival of one or two outsiders from across the Sound every few years would introduce enough genetic variation to mediate those effects.

Especially on an island, a new top predator would also likely “upset the applecart” as Ben David put it. A study on the ecology of the eastern coyote produced by the Wildlife Conservation Society put it a little more specifically: “As a top-predator, the potential for direct and indirect influences on a broad array of organisms and habitats are great.”

The key ecological concept lurking behind any speculation about those “top-down direct and indirect impacts” is something called the Mesopredator Release Hypothesis (MRH), which posits simply that the presence of larger predators will limit the populations of smaller predators. Using MRH to explore a hypothetical coyotes-get-established scenario, one starts by listing the existing smaller predators – mesopredators – raccoons, skunks, feral cats, crows, rats. Then one determines as best as possible the extent to which a population of coyotes is likely to impact those populations, either through direct predation or through competition for shared prey species, such as mice, rabbits, and ground-nesting birds. Finally, one outlines how changes in all those populations might cascade through all of those many ecological relationships.

Still, the outcome is rarely straightforward. Take ticks for a particularly tangled example. As Johnson explained, one might expect coyotes to decimate the rodent population and therefore reduce the population of ticks, which spend part of their life cycle on rodents. Studies elsewhere, however, have shown that coyotes’ negative impact on predators of rodents can outweigh their direct impact on rodents – thus increasing the total number of rodents in the system and, with them, ticks. Add to the mix the coyote’s eat-anything diet and the lack of conclusive research about the eastern coyote’s ecology and it gets messy fast.

“We have general parameters that we think they’re going to work within,” Johnson hedged, reluctant to say anything too definitive about the hypothetical outcome of a hypothetical coyote invasion. “That’s why I’m not going to tell you what the impacts will be. Because I don’t know.”

Last September, I decided I’d try to get my eyes on this coyote (possibly coyotes) I’d been hearing so much about. Ben David assured me it would be about as likely as winning the lottery. I’d be better off just keeping my eyes peeled while driving around the Island at night. Still, I had to try. In science you have to have confirmation.

At dusk, I drove down Meetinghouse Way in Katama, where a coyote had most recently been caught on camera. I carefully scanned the bushes with my headlights, surely deluded. Though this coyote was likely a transient, without a defined territory, I thought it possible it would have stayed around this area since July, enjoying a lonely Eden of rabbit and goose. I went at dusk because I knew coyotes are crepuscular animals, most active at twilight. It was just after a rain, and the sky was about as crepuscular as it gets.

According to biologist Way’s book Suburban Howls: Tracking the Eastern Coyote in Urban Massachusetts (Dog Ear Publishing, 2007), the literature recommends doing a series of three separate howlings, approximately one to two minutes apart. I pulled over and let one loose into the woods. I wondered if the neighbors could hear me. I wondered if Ben David would get a call in the morning about the pack of cougars someone heard howling all night. I wondered if the coyote could hear me, but characteristically sly, knew me for an impostor. One minute. Two minutes. Nothing. I howled again, the classic: AW AW AW AWOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO! Probably more wolf than coyote, but maybe that was just right for a coywolf.

Standing there listening, I remembered that Katama was where those foxes had been released all those years ago and how they’d come and gone so quickly at the whim of people. Now, once again, people were deciding how to deal with a new predator who, in a narrow sense, had come of its own volition, but in a broad sense had come because of people, seizing opportunities created by centuries of our short-sighted transformations of the continent. I thought about an undergrad thesis from the ’60s by someone named Adrienne Bowditch I stumbled across while researching this story. Her thesis was about mice, but its introduction seemed as relevant to coyotes here as anything else I’d read. “Not only is the island of Martha’s Vineyard isolated effectively from extensive restocking from the mainland,” wrote Bowditch, “but this island has a long history of human habitation and its terrestrial mammalian community stands as a vivid example of population changes and imbalances resulting from man’s intervention to control his environment.” The coyote, if it does find a way to stay, should fit right in.

One minute. Still nothing. I didn’t come expecting to win the lottery, but I felt disappointed nonetheless. I wanted to hear the woods answer back. A call would have seemed to say, We are beyond your control. Life is always returning. Or something like that. Two minutes. Nada. Shoot. In the quiet, I threw my head back a final time and ushered in the night.

6 comments

6 comments

Comments (6)