For a time, Aquinnah-based bookbinder Mary Elizabeth Pratt, better known as “Mitzi,” was something of a living legend. People at the far end of the Island told stories of the woman who lived alone on Moshup Trail, an artist who worked at her dining room table, in a half-finished house with a trailer full of furniture out front.

“I was at a party one time and somebody said, ‘You know, you’re an inspiration to single women living and working in Aquinnah,’” she laughed. We sat around that same dining room table, in the same house, now mostly finished, the trailer long gone. “I couldn’t believe it.”

Pratt, who grew up summering on the Island, hadn’t set out to be an inspiration; all she knew was that she wanted a job that would allow her to live here year-round. “I just knew that I wanted to do something here that wasn’t in the tourist industry,” she said. “I didn’t want to be in the boom and bust.”

As a young woman living in Boston, where she worked at Loyal Protective Life Insurance Company, Pratt decided she was ready for a new direction. “I was working as a mail clerk and they started pushing me up the ladder, which freaked me right out. I did not want to get stuck in a life insurance company.”

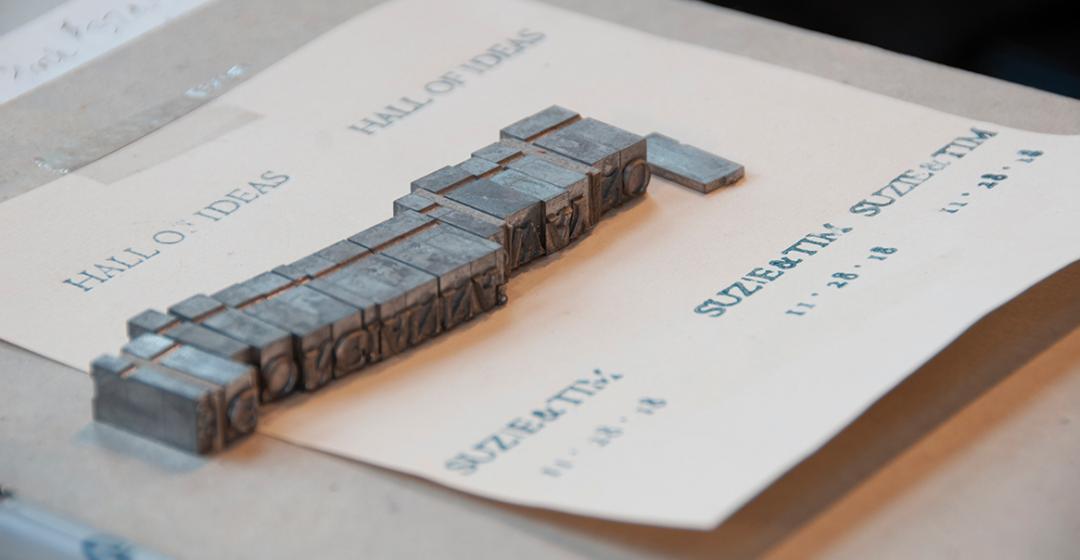

While walking with a friend down Newbury Street, a well-placed flyer caught her eye. “We looked down and there was a little flyer about bookbinding,” she remembered. Her friend asked her if she’d ever thought about becoming a bookbinder. “I said, ‘What’s that?’”

As it happened, her sister Noni was in college in western Massachusetts, where some of the most notable bookbinders were taking on apprentices. Pratt went on to work under David Bourbeau and his teacher, master German bookbinder Arno Werner. She was commuting back and forth to the Island, but soon settled into her Aquinnah home full-time.

Her legendary single status took a turn in the early 2000s, when guitar maker Flip Scipio was visiting some friends and happened to meet her on the beach. “I came up to Aquinnah one day to visit a friend of mine,” remembered Scipio, who was born in the Netherlands but has lived in the United States for decades. “We went for a walk on the beach and ran into Mitzi. We had dinner and I remember being in the kitchen and we’re talking about books, food, tools – she had more scissors than anybody I had ever met.”

“He called me ‘Cutter,’” Pratt added. “Well, first, he called me ‘Staples.’”

“I’d ask for a weird item and she’d have two,” Scipio said.

“Living up here, you gotta be well stocked up,” Pratt said.

“I don’t like to go to town very often.”

The happenstance meeting felt big for both of them, but bigger for Scipio, who had a hunch he’d be the one relocating. “I went home and realized my life had made this major turn, and I better get used to it very soon.”

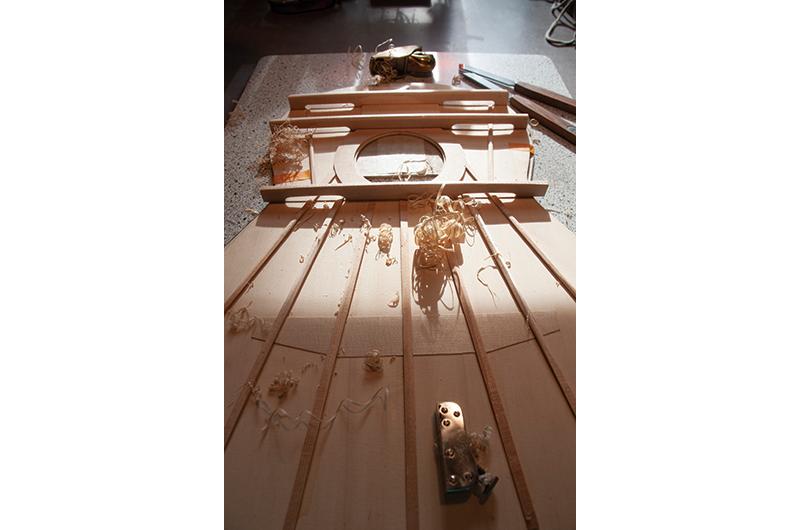

Eventually he moved in and the two finished a garage studio project that Pratt had started years earlier. Today, the structure houses his and hers studios: Pratt’s bookbinding operation happens upstairs, while downstairs in an open bay are all of Scipio’s guitars, the ones he’s built and the ones he’s commissioned to repair (for the likes of Ry Cooder, Paul Simon, and Rosanne Cash).

Together, the couple toured me through both studios, finishing each other’s sentences and demonstrating an easy familiarity with the landscape of one another’s work. Though their chosen disciplines are different, both share a fastidious approach to craft and a reverence for the past, for the way things have always been done.

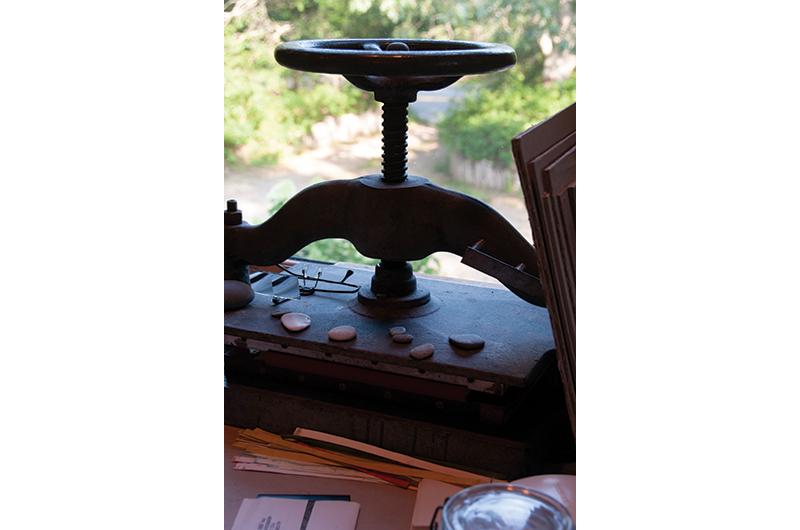

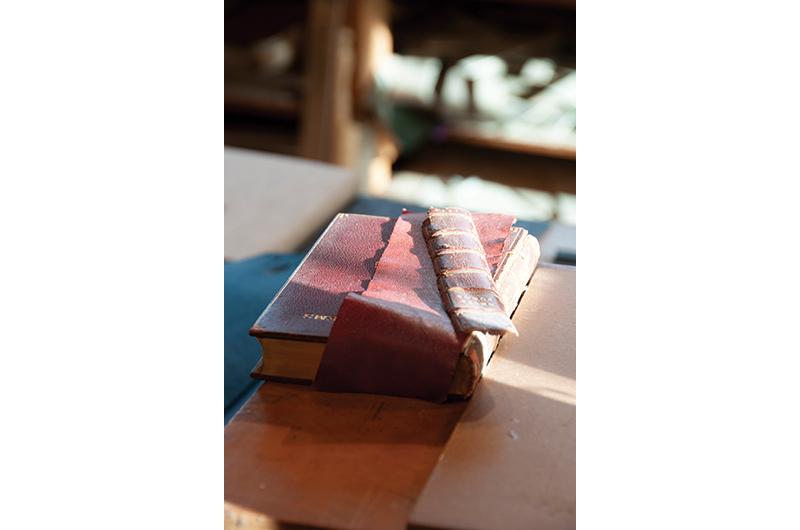

“We have very similar experiences with materials that we can’t get any longer,” Scipio said, taking a seat while Pratt pointed out her press and embossing machines, stacks of paper and leather, and the found treasures she uses to adorn many of her handmade books. Custom commissions and word of mouth sales of her blank volumes mean she doesn’t need to sell through traditional retail outlets; she has also taken on more restoration work, such as the Union Chapel’s bible in Oak Bluffs.

Repairing old instruments is another form of restoration, and Pratt has noticed parallels in their processes. “I’ve observed what we have in common is that you really need to look at the thing and be with it for a while before you even start working on it. How was it structured originally? What materials were used? I need to have that feeling of familiarity with the object in order to be brave enough to start cutting it or something.”

“It’s part of the reason why I like repair so much,” Scipio added. “You get to meet these people you’d never otherwise meet and you hear their stories. All of the books and all of the guitars have stories.”

Sometimes stories find them long after a project has been completed. Pratt remembered a particular series of journals she was working on for a while. Called a dos-à-dos, each book is divided into two parts. A woman purchased one and when Pratt ran into her a year or so later, the woman revealed that the book had saved her marriage. “They were having a hard time and they started to write to each other in the book,” Pratt said.

Downstairs in Scipio’s studio, Pratt searched for sketches and designs among the guitar parts and instruments that covered every available surface. Scipio received his first guitar as a young teen in Amsterdam. “My parents had taken one of those blessed parental vacations without the kids, which was a treat for them, and they went to the Canary Islands. They came back with a guitar for me, which was a surprise because I never really asked for a guitar. I was always just drawing.”

Scipio discovered that he liked playing the guitar, mostly for the sound it made. “It had this really beautiful sound, it was kind of my little blue blanket,” he said.

One day, biking home from a lesson, his guitar cracked. “I remember I found my dad in his light-blue swimming trunks sitting on a folding chair with my guitar and he had covered the cracked side with Bondo,” Scipio said, disgust still alive in his voice.

“That was my guitar, and the rosewood was now covered in gray goop, and I was just enraged. But you didn’t get angry at my father....He had a very bad temper.”

Instead, young Scipio decided he’d fix the guitar himself. “I got interested in it right away,” he said. “I got this incredible pushback right away from my father, and then from my neighborhood, like: ‘You want to make guitars?’

“You know, these days I probably would have been diagnosed as something, but at that time I was just a really annoying kid. I was just so anxious, and playing guitar, just plucking the strings, was something that released tension. I just kind of liked it.”

Scipio went on to study guitar making in Spain and England before making his way to the States. Though he had found a job in Nashville, a visa hiccup delayed his trip. In order to obtain a work permit he needed to prove that he was “preeminent in the field” of guitar making. “This was Reagan era,” Scipio explained. “I have a letter that says that I’m not preeminent in the field because I hadn’t made a guitar for either Andrés Segovia or Roy Clark or Chet Atkins.”

“That was in the letter,” Pratt interrupted with a laugh. “Can you imagine some dude at the INS writing that?”

Scipio shook his head. “No disrespect to Roy Clark, who was a really good picker, but I mean, come on.”

When Scipio finally arrived Stateside, the Nashville job was gone, but one had opened up in the Guild Guitar Company in Westerly, Rhode Island. When that factory closed, Scipio moved to New York and ran the famous Mandolin Brothers guitar shop in Staten Island.

These days, Pratt and Scipio divide their time between Aquinnah and Brooklyn, where Scipio’s business is still based. But after years of world traveling and the back and forth of seasonal life, they’re looking forward to calling the Island home.

“The Island is interesting because it’s circular,” Scipio said. “The world is circular, but this is on a much smaller circle. You’re going to run into the same people, so you’d better be careful what you say to whom, because you might run into them again. In New York everybody gives each other the finger for the smallest thing. Here you might run into them at dinner.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)