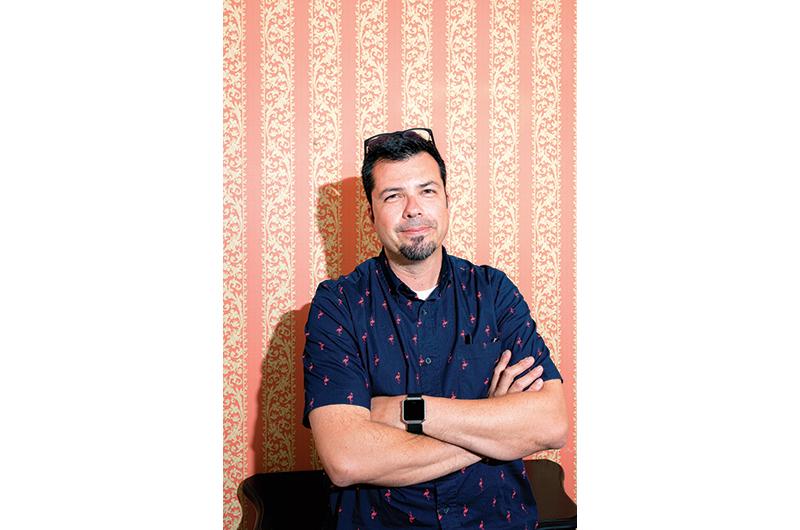

Daniel Cooney keeps a tommy gun in his studio. It’s not real – relax – it’s a replica. But it is convincing. “I have two,” Cooney told me in his West Tisbury home. “That one you can’t take apart,” he said, referring to the big one leaned against the wall in the corner. “It’s made of actual wood and everything.”

Behind him on the windowsill were other replicas, not of guns, but of figures from the Marvel Universe and Alan Moore masterpieces such as Watchmen and V for Vendetta. Below the action figures were some containers of brushes, pens, and jars of paint. Taking up most of the space in the room to the right was a drafting table tacked up with pencil sketches of 1920s Chicago, scenes from Double-Cross On Maiden Lane, the forthcoming installment in Cooney’s graphic novel series The Tommy Gun Dolls.

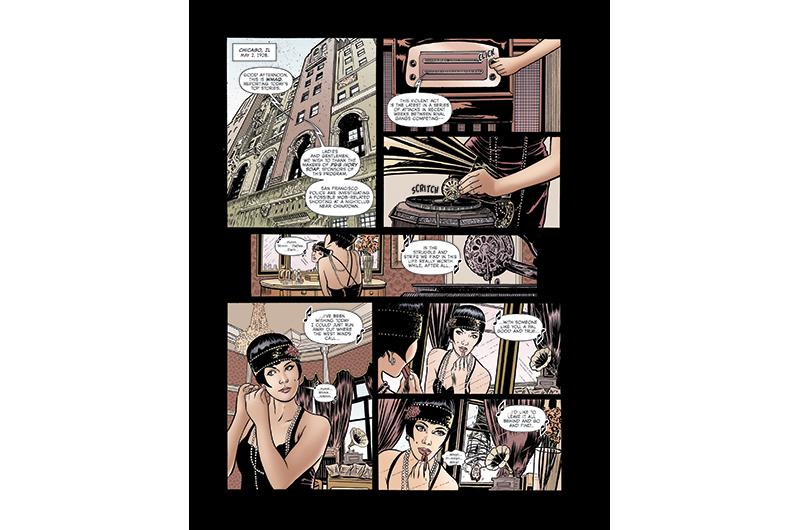

The first installment, The Big Knockover, published by Cooney’s Red Eye Press in 2017, takes place in the speakeasies and brothels of Prohibition-era San Francisco. In it, a crew of dancers and prostitutes, tired of being treated like property by rival gangs, takes up arms against their oppressors and becomes a sisterhood of punk-flapper-vigilante-thieves. The press christens them “The Tommy Gun Dolls” because, like any 1920s-era outlaws worth their salt, they use tommy guns to terrorize the public. Hence the gun replicas in Cooney’s studio. To inform his illustrations for the first volume, he staged a photo shoot with models in flapper garb at a vintage car museum. In addition to corsets, derby hats, and fishnet stockings, the models wielded the guns.

“If it’s just a fake toy, it doesn’t look right,” explained Cooney. “Just how heavy and cumbersome they can be. They’re not meant for accuracy. They’re just meant to scare.”

Historical accuracy, however, is central to Cooney’s work. The pages of The Tommy Gun Dolls are packed with the results of his research into 1920s America. “I think the architecture drew me into the era first,” he said of the art deco in the background of all the gritty crime drama. “Then I started learning about the jazz, the ragtime, Harlem Renaissance, Bessie Smith, Josephine Baker. I was like, ‘Wow this is an interesting era – I want to do a story set in the twenties.’ And I wasn’t quite landing what I wanted to do yet. It was gonna be a mobster tale. But I felt like, well, jeez, those are a dime a dozen.”

The necessary spark, however, came not from the Roaring Twenties but from a cross-dressing, Gold Rush–era renegade named Jeanne Bonnet that Cooney discovered while perusing a true crime book at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, where he taught illustration. “The look didn’t come to me just yet, but I saw the machinations of the character and her inner workings as a grifter-slash-con artist. But I still needed that hook. What’s gonna be the motivating thing for the story to get going? And I thought, ‘Okay, a murder mystery.’”

With a sense of the plot and the Prohibition milieu, he still needed a distinctive look. Something inspired by historical details that would support the vigilante action. He started thinking about flappers and the politics of women’s liberation behind their dress. And he wanted something practical, something a lady could wear to a bank robbery. So for the main character of The Tommy Gun Dolls, Frankie Broadstreet, based on the real-life Jeanne Bonnet, he modified the corset to go over a white button-up shirt and swapped the bell-shaped hat for a derby. A man’s hat. He had the look. “I liked that duality,” said Cooney. “And that worked well with low-lit places, speakeasies. Hustler, gambler, con artist…it just started to write itself.”

Which is not to say it wrote itself quickly. That was in 2005. Nine years later he would finally sit down and actually begin the first volume. Two years later, it was completed. Cooney, then living in California, where he is from, was conceptualizing the book around teaching, other comic projects, and his growing family. His first son, Dashiell, was born in 2009, followed by Dexter in 2012. (Yes, Cooney is a longtime fan of noir crime fiction and of Dashiell Hammett, who lived for a time on the Island, but he swears he just liked the name.) By the time Dexter came along, Cooney had moved to the Vineyard from the Bay Area to help care for his grandmother-in-law, only to contract Lyme disease. “So that kind of hindered me from the grip of the pencil. The arthritis pains. Just the fatigue of having Lyme,” he said.

He was also crowdfunding The Tommy Gun Dolls through Kickstarter, which can be a lot of work in itself. “I was overwhelmed, anxious, excited. I had a lot of self-doubt whether I could even fund it,” he said. But the Lyme receded, the crowd came through, including a number of Vineyarders who contributed editing and feedback, and the book debuted at Boston Comic Con in 2017.

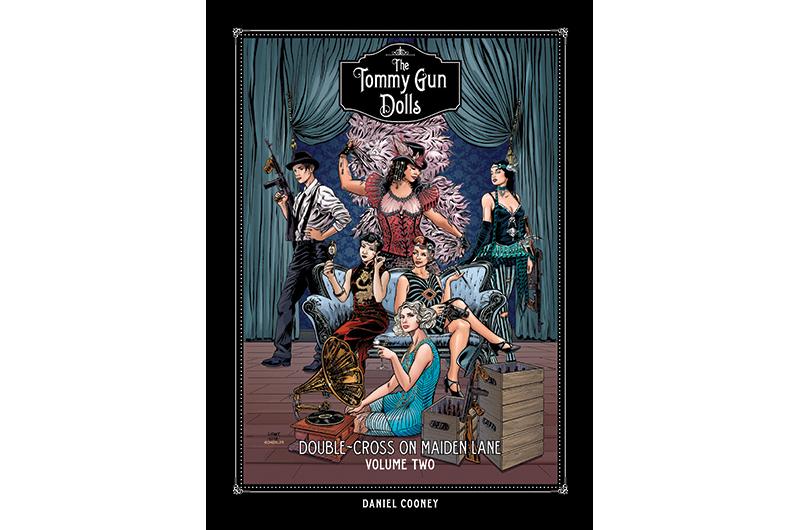

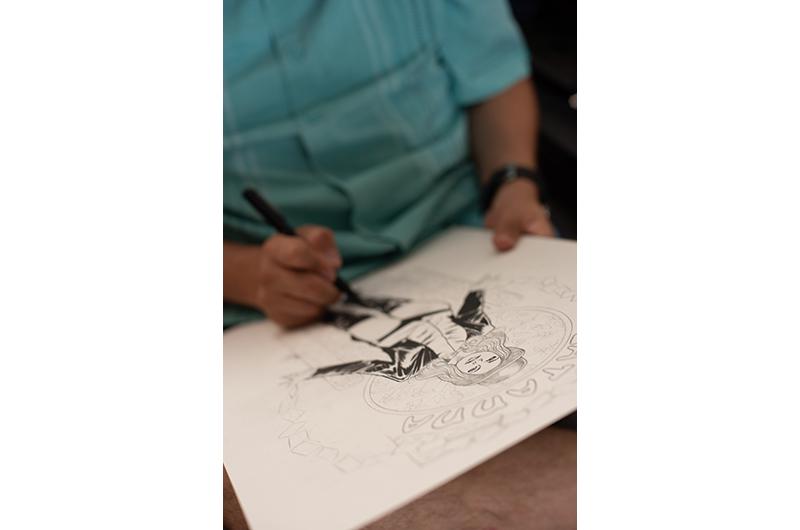

Even without life getting in the way, the creation of a graphic novel is slow, meticulous work. Cooney handed me a thick stack of twelve by twenty-four pages to demonstrate. “Oop, I spilled coffee on the top of them. They’re worth more, I guess,” he laughed. Called “penciled pages” in the biz, the stack represented something like a manuscript for Double-Cross On Maiden Lane, the second volume of the series, which he has been working on creating and crowdfunding for the past two years. The elaborately detailed pages were the comic without ink or text, a pencil-drawn version of the final product. The next step in the process, called “inking,” entails tracing back over every pencil line with an ink pen, which can take up to eighteen hours per page. Each page is then scanned, and text and other effects are added on the computer. One begins to understand why it takes so long to finish one of these things.

But even in the unfinished form of the penciled pages, Cooney’s skill and attention to detail as a graphic artist were obvious. In one frame, a shadow-shrouded figure held down a window blind with a slender finger to peer down at a parking lot. The simple lines and shades were full of intrigue. In another, the Tommy Gun Dolls lounged on a satisfyingly art deco Chicago street, where they had taken refuge after fleeing San Francisco at the end of Volume 1. Each character had her own personality of expression, posture, and costume. They were individuals. They were protagonists. They were women. And they were, for the most part, fully dressed. In 2019 you might shrug, but in comics, being all of those things at once used to be pretty rare.

“When I started out in comics in the early nineties, the first comic convention, it was male-dominated,” said Cooney. “So the only time I’d see [a] girl or woman at a show, they usually worked for their dad as a vendor, or they were there with their boyfriend, or their boyfriend was an artist and she was an aspiring artist. As we moved on into the nineties, and I got to intern at Marvel Comics, I got to intern for the only two female editors in the Marvel bull pen at that time in 1998….They dealt with a lot of stuff. I mean the comments and the art that comes in. I mean superheroes, you’re drawing nudes with latex on as decoration.”

Cooney felt it was absurd that Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, the Supergirls, whoever, were drawn fighting crime with warped anatomy and revealing supersuits – “scantily clad,” as he put it. His first comic series, Valentine, published in 1997, about a gun-for-hire in a gritty crime world, set his work apart from the female superhero mainstream right off the bat. “When that character came out she’s wearing a jacket and she’s got pants on,” he said. “She’s not looking like she just walked off a centerfold shoot for Playboy and now she’s a superhero.”

Cooney was an undergrad at the time and he remembers one of his professors felt he’d have trouble finding an audience for Valentine without, you know, cleavage, but the professor proved to be wrong. “I never really exploited [Valentine],” said Cooney. “And that’s why I think I have a lot of women readers....As the nineties wore on, you started seeing women writers, artists, more women going to cons. And they were buying my book. And some cons, even today, there’s more women that buy my book than men.”

Now with The Tommy Gun Dolls, Cooney continues with what worked in Valentine: fully-realized female protagonists, angry and armed. And while he imagines himself one day writing about women who don’t have to fight (or incite) crime to be empowered, it’s not likely to happen in Volume 2, at least not with this vigilante crew. There are still a lot of bad guys out there and besides, what else is one supposed to do with all those historically accurate tommy guns?