The Ag Fair. The Martha’s Vineyard Livestock Show and Fair. The Fair. Whatever you call it, for four days and three nights in August all roads on the Vineyard seem to lead there.

Indisputably the highest point of the Island’s high season, the fair draws thousands of daily visitors to the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society fairgrounds in West Tisbury. Locals, summer people, and tourists alike throng to the exhibition hall and barns to view the best of the season – the ripest tomatoes, the sweetest corn, the freshest eggs and pies and cakes, and hundreds of other entries. Crowds cheer for their favorites in the tug of war, shellfish shucking, and cornhusking contests. There’s even a smoked fish competition.

It’s as if the entire Vineyard summer is being condensed into these few kaleidoscopic days and nights as part of a ritual to celebrate and save its treasures along with those of all the other summers – 157 of them since the fair began.

In the weeks before opening day, rides and booths start turning up in the fields around the Agricultural Hall, as if to say “it won’t be long now.” One day before the fair, the entries begin to arrive: art and photography and needle crafts, preserves and honey. Perishable items are dropped off at first light the following morning: just-baked pies and bread, just-picked vegetables and intricate flower arrangements. By the time the fair gates open on the first day, the hall is packed – literally to its rafters – with hundreds of exhibits. Professional artists, bakers, and farmers compete for different prizes than hobbyists, home cooks, and backyard enthusiasts.

The barns and animal pens are filled with livestock: chickens, ducks, and turkeys in cages, a sow nursing piglets, a cow and her calf. Blue, red, green, and white ribbons mark the decisions of fair judges, who occasionally add an award of special merit.

Outside, equestrians promenade high-stepping horses in the riding ring, herd dogs show their skills at rounding up flocks, and wool-burdened sheep endure demonstration shearings. Special events include the woodsmen’s contest, where men and women race the clock and each other in a series of contests with saws and axes; the women’s skillet toss, a popular competition that turned twenty last year; and a weight-pulling contest for vintage tractors.

Music is part of the ag fair as well: a strolling brass quintet plays show tunes and light classics, and bands perform on a soundstage.

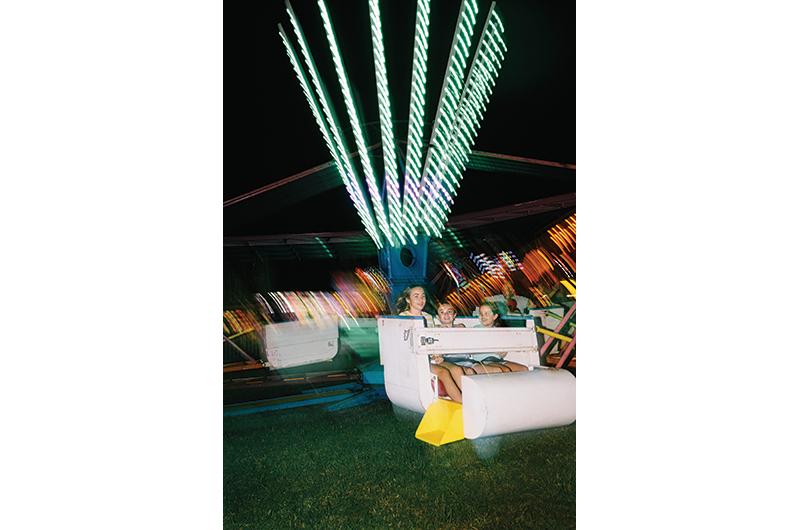

Opening day feels like summer might never end, particularly if you are young and have tickets for the midway. There’s a merry-go-round for the littlest ones, and more challenging carnival rides – the Zipper, the flying Musical Chairs, and the whirling Round Up – for tweens, teens, and adults. The fair closes at 11 p.m., offering a rare dose of nightlife for those under drinking age.

“It was the biggest thing since Christmas. Christmas and the fair – this is what we saved up our money for,” said Jim Athearn, a longtime agricultural society trustee and former society president and vice president, who grew up in West Tisbury in the 1950s and ’60s and co-founded Morning Glory Farm in 1975.

“I lived on Music Street, so I was within the sound of the fair – the roosters, the cows, the music from the merry-go-round,” he said. But what he and his brothers really craved was the midway, where they’d stay as late as their parents would allow.

“The Ferris wheel was my big attraction. I loved to get up high and look out over the great pond and the fields.” If the Athearn boys were lucky, one of the carnival workers might send them to Alley’s General Store for a soda and tip them a dime.

The price of a ride has gone up since Athearn’s youth, but then – as now – there was no escaping that the final day of the fair, a last blast of full-on fun as the days grow shorter and back-to-school deadlines loom, traditionally marks the beginning of the end of summer.

The Ferris wheel, merry-go-round, and other carnival attractions will be back for this year’s fair, the 158th since the agricultural society was founded. Drovers will again lead teams of oxen through their paces and craftspeople will card

and spin wool more or less exactly as in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, before industrialization made its way to American farms.

In those days, farming fairs generally took place in autumn, after the hardest work of harvest was over. The newly formed Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society held its first Fair & Cattle Show on a warm day in late October 1858. (It would be nearly thirty-five years before the first Ferris wheel made its debut at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.)

The agricultural society’s founders – including famed topographer Henry Whiting – were high-minded men of science who wanted to improve husbandry using modern methods to replace what Athearn called “the old scrub type of farming.” Prize-seeking entries, for instance a half-acre of corn, had to list all the fertilizers and growing procedures used.

“You were supposed to be sharing knowledge,” he said.

That first fair drew 1,800 people to see the livestock, baked goods, artworks, stitchery, and crops on display at the Dukes County Academy (now West Tisbury Town Hall). The event was so successful that the all-volunteer agricultural society constructed the Grange Hall, next door to the academy, the following year. An Island tradition was born, one that thrived and grew for most of the next ninety years, until World War II brought it to a halt in 1942.

Returning in 1946, the fair changed its dates from October to August. Martha’s Vineyard was shifting from a largely agrarian economy to one based increasingly on tourism, and the agricultural society reasoned that they needed summer visitors to keep the event going.

It worked. By the 1990s, the fair had outgrown the Grange Hall. In 1994 volunteers raised a disassembled, century-old New Hampshire barn in three days to create the new Agricultural Hall and the society moved to Panhandle Road. Last year, about 45,000 people passed through the fair’s entrance gate – nearly 12,000 on the first day alone. The closing Sunday saw 10,500 fairgoers, shredding the previous record of 4,700.

“Failure hasn’t been a dish that we’ve eaten lately,” said Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society president Brian Athearn. (Jim Athearn is his uncle; the family traces its Martha’s Vineyard lineage back twelve generations, with farmers in every one.) But despite this success with the fair – which funds nearly all the society’s operations – Brian Athearn, who took office in 2017, acknowledges that the past few years have been a difficult time for the nonprofit.

In particular, the agricultural society was feeling the fiscal pressure from financing its ambitious purchase of neighboring land from the Martha’s Vineyard Museum in 2012. A photovoltaic array on part of the purchased land took longer than expected to recoup its costs, adding to the society’s money woes. But things are looking brighter: the solar panels are now generating revenue and the Martha’s Vineyard Film Festival has made an offer to buy the land with a 999-year leaseback for the agricultural society’s array.

The society has also shaken up its sixteen-member board, adding a bylaw that limits terms in office in order to make room for new trustees. This policy could have been taken as a slap by the senior members, several of them lifelong Island farmers who have volunteered their time on the board for decades. Instead, some have chosen to stay on as honorary trustees, sharing their advice and experience without voting.

“The planets have aligned, and we have the board we have now to take the baton from the people who have forged what we have,” Brian Athearn said. “The people who came before us have been pioneers in the community.”

Paying staff is another recent development for the agricultural society, which ran on volunteer power for much of its history. As early as a week after the first fair in 1858, the Vineyard Gazette was already worried that society president Leavitt Thaxter might fall victim to burnout.

“But for him, and for his untiring labors, the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society would never have known an existence,” the newspaper said. “In the future, we trust, there will be a greater division of labor. Let each one do something towards the grand whole, and the labor of all will be light.”

This many-hands model worked well for the better part of 150 years, but began to flag in the twenty-first century as longtime volunteers aged out and fewer younger ones stepped up. The society hired Kristina West, who has served on its

board of trustees and also worked for the nonprofit Island Grown Initiative, as executive director this year. To coordinate the fair, the society in 2018 brought on longtime Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass & Bluefish Derby coordinator Amy

Coffey, who also has worked for NBC Sports planning Olympic coverage.

“The times were just changing,” said Rebecca Haag, who is the executive director of Island Grown Initiative and who joined the board of trustees of the agricultural society in 2018. “Places like the ag society and other nonprofits have been living off volunteer time for a long, long time – folks that have devoted hours and hours of time and energy to making the society work.”

Today, Haag said, “people just don’t have a lot of volunteer time, and the society finally realized we had to hire professional staff.”

Still, volunteers remain at the heart of the agricultural society. For a potluck supper to benefit Flat Point Farm after a catastrophic barn fire earlier this year, volunteer coordinator Kristy Rose wrangled nearly forty helpers, Brian Athearn said.

Volunteers also staff the annual Meat Ball and Barn Raisers’ Ball, and will be key to reviving the Living Local Harvest Festival. The popular autumn event last took place in 2017, but the society hopes to bring it back this year, possibly in conjunction with the annual Wild Food Challenge, and they added a Festa Junina – Brazil’s traditional harvest festival – to the calendar this year

as well.

In addition to Brazilian Islanders, Brian Athearn wants to connect with other Vineyarders who have not been part of the agricultural society’s traditional sphere. “I’m trying to have an outreach to the Muslim community and the orthodox Christian and Jewish communities to line up farmers with ethnic communities who are searching out lamb for the holidays,” he said.

From his own Runamok Farm in West Tisbury, he added, “I sell all my lambs exclusively to Muslims. It works great for the farmer,” because there’s no trip to the slaughterhouse off-Island and the customers return the animal’s pelt.

While he farms the land he lives on with his family, Brian Athearn also has a day job at the company he co-owns, MV Tech. It’s a duality that sometimes makes him envy the younger farmers on the agricultural society board.

“I farm part time, but I wish I could do what they’re doing,” he said. “They are actually making it happen. Jefferson Monroe at The GOOD Farm – he’s growing in a thoughtful way and providing a maximal amount of food to the community.

“The amount of energy they have is just breathtaking,” Brian Athearn said. “They’re tenacious!”

Another young farmer making an impact on the Vineyard’s agricultural community is Julie Scott, one of the society’s two vice presidents, who has been working with Brian Athearn to bring 4-H clubs back to the Vineyard.

Founded in the early twentieth century, 4-H is a network of local youth development clubs originally aimed at teaching rural youths to farm with modern methods – much in the spirit of the agricultural society’s founders. “4-H was for kids to get them learning and connected, sharing information, and getting involved with what happens on the farm,” Scott said. The program is still going strong on the Cape, across the country, and in more than fifty other nations, but it hasn’t existed on the Vineyard for years because the Island lacks a cooperative extension office to sponsor local clubs.

With no extension agent or funding, restarting 4-H on the Vineyard has been challenging, Scott said. But in August of last year, club leaders came forward, including Rebecca Gilbert of Native Earth Teaching Farm in Chilmark, whose Kids on the Roof club brings children and goats together, and preschool teacher Elizabeth Bonifacio runs a nature-inspired crafts group.

Future farmers of Martha’s Vineyard can draw encouragement from vibrant local operations, including Mermaid Farm and Dairy in Chilmark, Morning Glory Farm in Edgartown, Slip Away Farm on Chappaquiddick, and Flat Point Farm in West Tisbury, which received massive community donations to rebuild its barn after the fire.

These are just some of the best known of more than three dozen large and small farms on the Island. Some, such as Morning Glory and The Grey Barn and Farm in Chilmark, farm a diversity of products, including meat and vegetables. Others are more specialized: Martha’s Vineyard Mycological in Chilmark, for instance, grows only shiitake mushrooms.

The Vineyard also boasts multiple agricultural nonprofits with educational missions: The FARM Institute and Slough Farm, both in Katama, and Island Grown Initiative in Vineyard Haven.

When it comes to support for working farmers, however, there is only the agricultural society. If a cow or a sheep falls unusually ill, the society’s livestock emergency fund can help pay for its costly treatment, including a trip to specialist veterinarians off-Island, Scott said.

Farmers and backyard gardeners alike can apply for the society’s farmers grant program for funds to repair, improve, and innovate their growing operations.

“We really want to go back to being the organization that farmers can depend on, rely on, and come to for whatever they need, and that includes young people who are interested in farming,” Scott said.

“Ultimately, to make farming succeed in a place, you’ve got to have people who want to farm and who want to commit themselves to doing it,” Jim Athearn said.

“The demand is there. The land is even there. They don’t need charity or welfare; they just need the desire. These people are not commonly found. But you can’t have farms without farmers.”

And you can’t have a fair either.