The story of Lillian Hellman on Martha’s Vineyard could be a kind of fable for famous and important people. The moral? Whatever splendid things you did – and Hellman did a lot – you’ll more likely be remembered for that time you smoked a cigarette and dropped an f-bomb in the grocery store. Or that time you failed to pay the guy who moved your furniture from the Island to New York City. Or when you stole a fancy Virginia ham from your friend who just wanted to store it in your fridge because his fridge was too small and then cooked it all wrong and refused to admit it.

It seems everyone who remembers Hellman on the Vineyard has stories like these. They touch on her literary and personal accomplishments – her smash-hit plays on Broadway and in Hollywood, her best-selling and National Book Award–winning memoirs, her principled stance before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, her star-studded dinner parties. But what’s at the top of most Islanders’ memory piles is what might be called the dirt on Hellman. And it goes both ways. “There’s an inverse snobbishness and bootlicking of Islanders that is totally disgusting to me, and maybe to Islanders too,” a seventy-six-year-old Hellman once complained.

One Islander unwilling to bootlick was Hellman’s one-time editor Stan Hart, who, in a letter to the Vineyard Gazette after Hellman’s death, predicted she would sink into obscurity. “Who in 20 years will give a hoot for the collected works of Lillian Hellman?” he asked rhetorically. It’s been exactly thirty-five years now – she died on Martha’s Vineyard on the last day of June 1984 – and the answer is a lot of people. Her plays have enjoyed a number of recent revivals at theaters around the country, including a whole Lillian Hellman Festival at Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., in 2016. In 2017, her anti-fascist drama Watch on the Rhine opened at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis and Berkeley Repertory Theatre in California, and her 1936 flop Days to Come was mounted off-Broadway at the Beckett Theatre. This past winter The Lyric Stage Company of Boston staged perhaps her most famous play, The Little Foxes.

The program notes of the new productions tout her success as a female playwright and screenwriter in an industry that was dominated by men, as well as her victories and failures as a committed political voice in a time of intense polarization, as evidence that Hellman is more relevant than ever. But here on the Island that was her adopted home, the picture of a literary figure is rather less grand and has more to do with fishing.

Her first appearance in the three thick “Hellman, Lillian” envelopes in the archives of the Vineyard Gazette was in 1948, five or six years – Hellman can’t remember exactly – after she first stayed on a boat in Edgartown Harbor and fell in love, as one does. In the article, she was holed up in Margaret Webster’s house in Aquinnah (then Gay Head) working on a stage adaptation of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and deriding red-scared Hollywood for offering her a contract with stipulations about her political activities.

“They know I’m not a Communist, and yet they have the gall,” she gibed in her voice variously described as “deep and muscular,” “mellow,” “cigarette-husky,” “deep for a woman,” “whiskey-and-cigarettes baritone,” “full-throated rasp,” “a Vineyard fog-horn.” This particular afternoon the Gazette described “an extraordinarily attractive personality whose tongue is sharp, eyes alive and whose light brown hair is done in loose halo fashion about her head,” the hair no doubt a special effect of the Marcel blonde hairdo she maintained till her death. Asked to relate her life story Hellman replied, “It’s boring,

I promise you. Still want it?”

The following summer found Hellman interrupting an interview that was supposed to be with her longtime companion Dashiell Hammett, who was visiting her in Gay Head. The two met in Hollywood in the ’30s and, like many intellectuals troubled by the brutalities of the Spanish Civil War, became regulars in anti-fascist circles. As Hammett went on in his hardboiled way about his hardboiled detective fiction and service in World War II, Hellman found ways to enter and reenter with drinks and commentary, leaving the reader with the sense that if there was an interview happening somewhere, Hellman would find her way into it. As Peter Feibleman, another companion of hers, put it, she “could upstage God.”

She soon had an opportunity to upstage Congress. For both Hellman and Hammett, their political alliances during the ’30s would be damning evidence of subversive behavior by the ’50s. In 1952, she was summoned to testify about communist activity in Hollywood before the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). She wrote back that she would testify about herself but not her colleagues, virtually guaranteeing she would be blacklisted from work as a screenwriter. Her letter is famous for the zinger: “I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions....” Hammett also had his day before the HUAC and spent five months in prison for refusing to testify.

The effects of the blacklist rippled back to the Vineyard in at least one way. Hellman, unable to find work in Hollywood, was forced to sell the beloved farm she owned in Westchester County. She wrote in her memoir Scoundrel Time about the period: “I am angry that corrupt and unjust men made me sell the only place that was ever right for me, but that doesn’t have much to do with anything anymore, because there have been other places and they do fine.” One of those places was the recently demolished Mill House in Vineyard Haven, which she bought for a song in 1955. She described the place, which was really three houses from three centuries cobbled together with four staircases, as “a howl of a house.…The Vineyard is a modest place, and my house is a modest house, as it should be.”

There, overlooking Vineyard Haven Harbor, she wrote her classic drama Toys in the Attic, a companion play to her earlier humdinger on avarice and Southern mores, The Little Foxes. By 1960, “loyal Vineyarders” were celebrating the play’s success in New York and praising “the Vineyard’s own, Lillian Hellman.” In an interview with the New York Herald Tribune, Hellman explained how she made some improvements to the attic of the Mill House in order to compose the play: “I like to wake up and go right to work. So I cracked through a wall and made a room with a sleeping end and a working end.”

The Mill House also had a Hellman end and a Hammett end. In the single skimpy envelope on “Hammett, Dashiell” in the Gazette archive, Hart remembered how “in 1955 or 1956 the rumor spread through Vineyard Haven that Lillian Hellman…had a man, Dashiell Hammett…up in her attic.” Hammett, stricken with chronic emphysema that had grown worse in prison, mostly stayed up there. He retreated to his tower when Hellman had guests over and responded to their inquiries almost entirely through her. His presence each summer introduced some mystery and gloom into Hellman’s glamorous social habitat. In The Paris Review Anne Hollander and John Marquand, who were picnic buddies of Hellman’s, described Hammett “walking in delicate silence, in the cruel wasting of his illness, down a crowded sidewalk on his way to the library, unrecognized, unknown, forgotten, the proudness of his bearing [setting] him off from the summer people.”

This was a dark period for their relationship. He: sick, beaten-down, a chronic alcoholic, and unable to write. She: hustling to restore a career derailed by political insanity while still caring for him. She wrote of their last four years together, “Not all of that time was easy, and some of it was very bad, but it was an unspoken pleasure that having come together so many years before, ruined so much, and repaired a little, we had endured.”

Hellman’s thirty-year relationship with “Dash” ended with his death in 1961. Not long after, she decided the Mill House was too “crazy” to maintain, sold it, and broke ground on a new one down the road right on the harbor. It was her insistence that the house be built “within six months of when they promised,” she later said, that first gained her a reputation for being “difficult.”

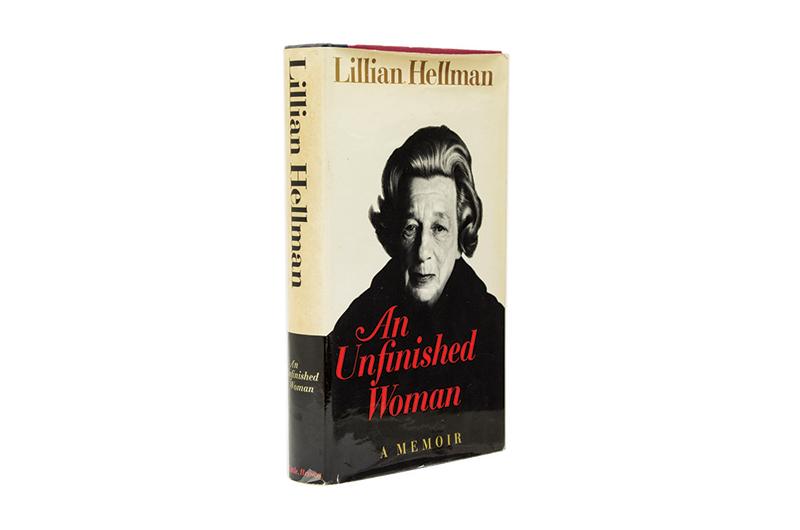

Through the mid-1970s she spent early spring through “late late fall” there on “Writer’s Row,” along with her neighbors William Styron, John Hersey, Mike Wallace, Art Buchwald, and others. During that time she spent her mornings writing two memoirs, An Unfinished Woman – which won the National Book Award in 1970 – and Pentimento. She used the rest of the day to establish herself as queen bee of that particular social scene.

“As a hostess she was terrific,” remembered her friend and neighbor Rose Styron. “She would get very interesting people to come to her dinners, which were swell. But she did not want to be upstaged in our house or her house and she left our table twice because she felt in each case that there was someone there who was getting a lot more attention than she was. Once it was Frank Sinatra, who she denigrated.”

As a teenager the then-aspiring writer Rosemary Mahoney spent the summer of 1978 as Hellman’s personal cook and housekeeper and later wrote a book about it. “It was really important to her to have the most famous people on the Island to her house,” she remembered. “If a person was successful or famous she would just call them up and say, ‘This is Lillian Hellman.…’” Sometimes this led to jockeying among the neighbors. Once, for instance, when Hellman heard that Jackie Kennedy might be visiting the Styrons, she disinvited them from a party she pretended she was having in an effort to sow jealousy.

Styron attributes Hellman’s obsession with celebrity to her competitive bent, something Styron first recognized when she caught Hellman cheating during their regular Scrabble game on the lawn. “I thought it was amusing and I never called her on it,” she recalled with a smile, “and I still beat her most of the time.” Robert Brustein, theater director and another of Hellman’s Island friends, politely speculates that keeping the house full of well-known people might just have been a way for Hellman to fill the absence of Hammett.

For friends and famous dinner guests she’d pull out all of the stops, spending hours deciding menus and harvesting fresh herbs from her garden. Former guests remember excellent and elaborate meals inspired by her New Orleans upbringing, which she prepared herself with help from her cook. Little did they know, as Mahoney explained to me, she often topped off her expensive vodka bottles with the cheap stuff. There were also the jousts with fellow Southerner William Styron over how best to serve a Virginia ham – chunks or slices? Hot or cold? – or how best to salt black-eyed peas. And apparently she didn’t like children around the table. Brustein remembered how she could hear them and smell them around and would growl like some kind of ogre, “Is there a boy in here?”

In his eulogy for Hellman, the cartoonist Jules Feiffer described her holding court. “Her presence, even her thin-waisted presence, was still enough to dominate in dinner parties. I have often found myself marveling in dazzlement, envy, and awe at Lillian’s ability to hold the attention of a room with a story which when examined later had all the importance of a marketing trip to Cronig’s.”

Of course, those trips to Cronig’s might have been more eventful than Feiffer knew. One woman who worked at Cronig’s when Hellman frequented the store explained that she behaved as though she were the only customer that mattered. And Mahoney remembered employees at the store wincing when she told them she was working for Hellman. “They looked at me like, ‘Are you sure you really want to do that?’”

Hellman’s ace in the hole as a hostess, however, was her fishing. Not only did bluefish caught and smoked by her end up on the dinner table, she took lucky friends out with her on writer John Hersey’s boat for antics off West Chop. “She took Bill and Lenny [Leonard Bernstein] and me out once and Lenny was appalled, but we won’t go into that,” recalled Styron.

Styron might have been alluding to Hellman’s propensity to skinny dip without giving a damn who saw. Or perhaps what appalled “Lenny Pie” was what Jennifer Phillips, another fishing companion of Hellman’s, described. “She explained her own navigational methods: She just got on a boat with a bottle of whiskey and a huge supply of emergency flares.” Or maybe it was what Jack Koontz, who co-owned a twenty-three-foot fishing boat with Hellman, remembered about his co-captain’s response whenever another boat passed closer than she liked: “She always did the same thing. She sat until the boat began to churn in the wake, then she got angry, grabbed the rail, stood up, and gave the guy the finger.”

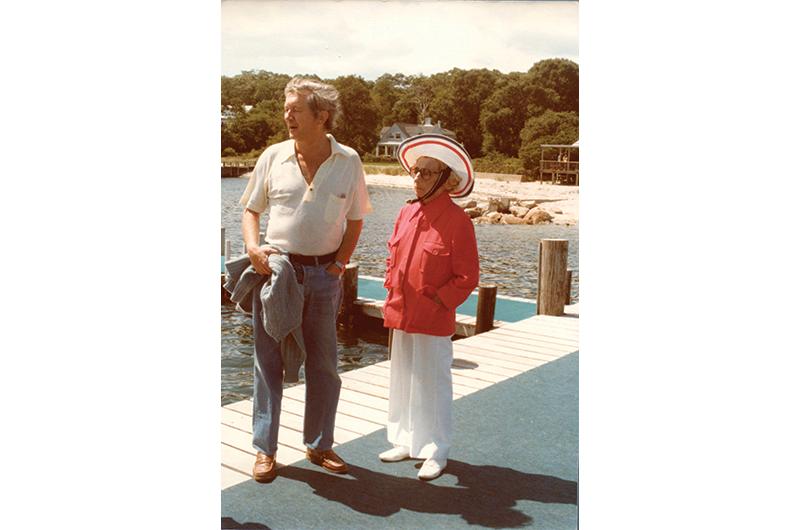

A number of people who knew Hellman agreed that she was at her best, or at least her most tranquil, fishing on the water. Decked out in her fishing uniform of a wide straw hat and pants, she fished and chain smoked and reminisced about fishing with Hammett. But, as she wrote in An Unfinished Woman, she was just as happy to fish alone.

“In many places I have spent many days on small boats. Beginning with the gutters of New Orleans, I have been excited about what lives in the water and lies along its edges. In the last twenty years, the waters have been the bays, ponds and ocean of Martha’s Vineyard, and autumn, when most people have left the island, is the best time for beaching the boat on a long day’s picnic by myself – other people on a boat often change the day into something strained, a trip with a purpose – when I fish, read, wade in and out, and save the afternoon for digging and mucking about on the edge of the shore. I have seldom found much: I like to look at periwinkles and mussels, driftwood, shells, horseshoe crabs, gull feathers, the small fry of bass and blues, the remarkable skin of a dead sand shark, the shining life in rockweed.”

In 1973, Hellman told Nora Ephron from The New York Times, “I’m totally unequipped for getting older. Nobody ever told me I was going to get older.” By 1975, in addition to a series of small strokes, she developed emphysema and doctors recommended she stop smoking (five to seven packs a day!) and reduce her Vineyard season to the summer months. Her glaucoma worsened and she spent the last few years of her life nearly blind.

These problems only made her difficult manner worse. Mahoney explained, “She didn’t [age] with much equanimity. She was often in a bad mood because of it.”

A number of bitter and complex challenges to her reputation during that last decade of her life also contributed to her irascibility. After the publication of Scoundrel Time in 1976, she was the subject of a number of attacks about past sympathies and apologies for Stalinism and her dishonesty about them. In 1979, novelist Mary McCarthy fanned the flame by claiming on The Dick Cavett Show that everything Hellman wrote “is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.’”

Hellman immediately filed suit for libel. Though she died before the suit went to trial, the conflict dredged up many old social and political rivalries and permanently marred her reputation. The scrutiny of her memoirs brought on by the case revealed fabrications – many of them self-serving – that some felt crossed the line of a writer’s license in memoir. On the Vineyard, the ordeal drove a wedge between Hellman and her friends from whom she expected absolute loyalty. She and William Styron did not speak to each other for an entire summer when he refused to write a letter in her defense.

Her health continued to deteriorate. “I can, of course, type without seeing, but I have a hard time reading back what I’ve written, so I’ve been trying to learn to dictate,” she told a reporter on the portico of her home in 1981. She was walking with a cane due to a fall outside a recent opening of a revival of The Little Foxes. And though she still went fishing twice a week, even if she had to be lifted into the boat, she sometimes had to forgo the bluefish for scup and flounder. She didn’t mention the conflict with McCarthy, but fumed about Vineyard Haven’s unresponsiveness to her repeated complaints about an odor that the wind would blow into her house off the harbor. And about the Reagan administration: “I think we are being run by ignorant and selfish men just now, but things will be much better after awhile. We have one virtue in this country. If we don’t like things, we change them.”

Hellman died in June three years later en route to Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. Her funeral was held at Abel’s Hill Cemetery in Chilmark where a number of characters from her years on the Vineyard delivered eulogies – Patricia Neal, Jules Feiffer, Robert Brustein, among others. One theme was her resilience through those final, most difficult years.

Annabel Nichols described how “she became ill and practically everything changed; everything that is except for the courage and the humor.” Peter Feibleman related a call six hours before she died in which she said to him, “I want to work, I want to work, I want to work.” William Styron spoke about their meal together the night before she died. After carrying her to the table, he realized “she was gasping for breath and she was suffering…and yet, I had a glimpse of, almost as if she was a young girl again, in New Orleans with a beau and having a wonderful time.”

Hersey explained that “Death became her enemy years ago, when Hammett died, and this enmity made her even more vibrant and alive. What could calm this anger? Only the sea, and money, and love.”

As for her reputation on what she once called “the tight little island of Martha’s Vineyard,” perhaps her own words say it best. “Any life can be made to look a mess of,” she said. “Mine certainly can.”

4 comments

4 comments

Comments (4)