Some ships have afterlives that far surpass their actual lives. Think of the Titanic. Its useful career lasted just five days, but in the wake of its sinking by that infamous iceberg has come a ceaseless flood of attention for more than a century: books, movies, expeditions of discovery, recriminations, theorizing, all making it the most famous ship in history, an archetype of glamour and vainglory. Far on the other end of the glamour spectrum from the opulent Titanic was the Port Hunter, a small, unassuming, relatively short-lived freighter that sank with no fatalities almost exactly one hundred years ago but that nonetheless had staying power. More than half a century of salvage attempts, both informal and formal, fueled by the accessibility of the wreck and speculation about its contents, kept the sunken ship afloat in the public imagination on the Island. Even today, a namesake Port Hunter restaurant in Edgartown is across the street from the Covington, a restaurant coined for the seagoing tugboat that sent the Port Hunter to its final resting place about a mile and a half from East Chop Light.

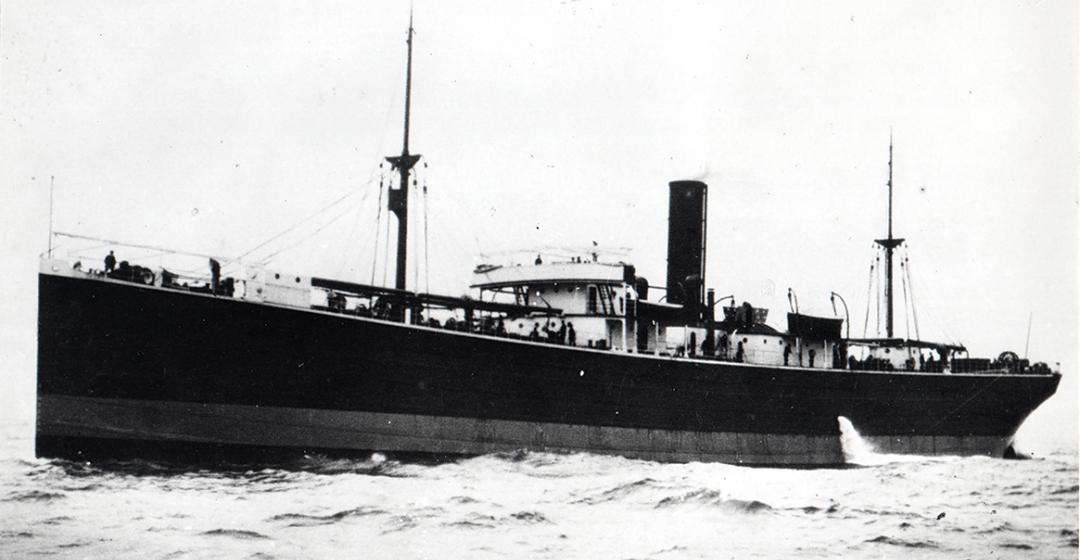

Constructed in 1906 at Hebburn-on-Tyne, United Kingdom, in the Newcastle shipbuilding area, the 380-foot-long, 4,062-ton Port Hunter was a no-frills workhorse with an open wheelhouse for visibility in all directions, a convention borrowed from sailing ships and still typical at the time, but that helped neither officer nor helmsman spot the Covington. When the collision occurred, at 1:48 a.m. on November 2, 1918, she was owned by a branch of the famous Cunard Line. But it was the final weeks of World War I, and the ship was sailing under the auspices of the U.S. Government, steaming from Boston under the command of Captain William Stafford toward New York City, where it was expected to join a convoy headed to Saint-Nazaire, France, with supplies to support American troops fighting in that country as well as materials for the French government.

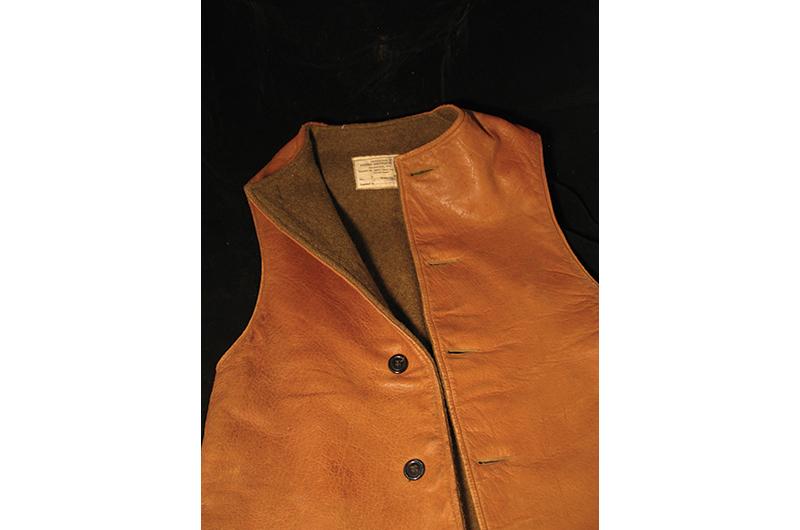

With only a single gun on its stern deck, the Port Hunter would have been a sitting duck for German U-boats (in fact, the Armistice was just nine days away) and so needed the protection a convoy offered if it was to deliver its miscellaneous cargo. Though various accounts disputed the specifics of the cargo list, it included steel billets, or bars, three inches in diameter and twelve feet long, and 800 sets of freight car wheels for the French. For the American troops there were bales of heavy underwear, woolen puttee leggings, 205,797 stylish, fleece-lined cowhide jerkins (or vests) worn by aviators, olive drab shirts, rubber boots, military candles that burn brightly and were used in the trenches by soldiers, and kits of cobblers’ tools. What it apparently did not include was gold bullion and fine French brandy, persistent rumors to the contrary.

Headed into Nantucket Sound from the opposite direction, up Vineyard Sound, was the Covington, towing a pair of Consolidated Company barges. Though at least one witness said it was foggy, and another brightly moonlit, most accounts agree it was a clear but moonless night and the breeze was light. As the Port Hunter neared the point between Falmouth and the Vineyard where Hedge Fence Shoal narrows the passage, whether through error or confusion the Covington knifed into the freighter some fifty feet aft of its port bow. (The pilot aboard the Port Hunter, Charles B. Paine, was found responsible and his license suspended, originally for ninety days, but eventually reduced.) The collision knocked twenty seamen aboard the Port Hunter from their bunks and opened a fifteen foot high and seven foot wide gash in the freighter’s hull plates.

No one was killed and only four were injured, but cascades of water poured into the Port Hunter that were far beyond the pumps’ ability to combat. In less than two hours the ship was gone – but not that far gone, as it came to rest on the shoal, leaving its wheelhouse, foredeck, and bow above water. Stafford is generally credited with the quick thinking to navigate the Port Hunter out of the channel and into shallow water, though some said that the Covington’s captain intentionally nudged the wounded freighter onto the western slope of the shoal, and one report had the Covington offering such help but being refused. Whoever did it, that maneuver led to what would be the Port Hunter’s real story, and one that would extend over seven decades: salvage and salvors.

Two small boats rushed immediately to the crew’s rescue, and survivors were brought to the Seaman’s Bethel in Vineyard Haven. “There were 53 men, including Captain Stafford,” the Vineyard Gazette reported at the time. “Many of the men were destitute of clothing and in many instances wore only shoes and trousers. The villagers had been notified of the coming of the survivors,” the Gazette continued, “and a committee, headed by Frank L. Eddy, manager of the telephone company, got together a large quantity of clothing, money, tobacco, food, fruit, etc., with which to welcome the ship-wrecked crew.” The Vineyard Haven chapter of the American Red Cross served dinner: “hot coffee, meat and bread and butter. The men of the town provided the smokes.”

The late Stan Lair was a teenager at the time. “After breakfast [on the morning of the sinking] I went downtown,” he recalled in a tape transcribed in 1995 by his grandson Chris Baer. “I saw a lot of English sailors around. I couldn’t quite figure out what was going on down there. Finally I got word what had happened.”

Meanwhile, a free-for-all among amateur salvors soon began. Word spread quickly that bales of goods had begun to float up from the wreck and were free for the harvesting, with a finders-keepers ethos fully in effect. Other items that didn’t liberate themselves could be had by fishing through the open hatches with bluefish jigs, eel spears, quahaug rakes, and grappling irons that Island blacksmiths were happy to hammer out on short notice. Certainly many Vineyard fishermen had the skills and boats needed for such purloining. Over time the legend grew of the many Vineyarders arrayed in garments that looked much as if they came from the Port Hunter trove.

“Eventually fishermen discovered there was nothing to prevent fishing for things other than fish,” a retrospective in the Gazette published a decade and a half after the event coyly suggested, “and soon the wharves and back yards of the Vineyard, the Elizabeth Islands, New Bedford, and various other places were littered with leather jerkins, Army puttees, rubber boots, shirts, and many other articles designed to make life more comfortable for men in the trenches of the Western Front.” Not needing puttees, Vineyarders fashioned them into blankets, quilts, rugs, and even long underwear, which proved none too comfortable.

“Everybody wore ‘Port Hunters,’” Robert Chapman, a long-time Islander who died in 2002, said to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s oral historian, Linsey Lee. “I grew up wearing ‘Port Hunters’ in the wintertime. Itchy itchies.” Lee herself reported that “you could still find [Port Hunter] candles in yard sales” into the twenty-first century.

“I recall one of my schoolmates” going to the wreck, Lair said on his tape. “He only had a little dory. He got out there, and he came in with a bale of these leather vests, how he ever did it I don’t know. But the method was to get over the holds with a long pole with a hook on it and hook this stuff up. But anyway, he had a hundred dollars in tow there, so he did all right….I also recall a dray load…of rubber boots going up past my house on Center Street. Just heaped right up with old rubber boots, well new rubber boots, that is. They were unlined, so they weren’t that great, but there they were.”

A nearly three-month delay by the American government in awarding an official contract to salvage the Port Hunter, possibly because it was a British ship and some of the cargo was French, gave the amateur salvors their window of opportunity. When the contract finally did come, in February 1919, it went to New Bedford’s Mercantile Wrecking Company, of which Barney Zeitz – great-uncle and namesake of the Vineyard artist – was proprietor. Also involved were Jacob Dreyfus and Sons, large wholesale merchants of Boston, and Michael J. Leahey of New Bedford. Zeitz had many business interests in New Bedford, including a hardware store, jewelry store, real estate office and, later, the Zeiterian Theatre.

This contract involved only the American portion of the cargo, valued at $3,800,000, less the $200,000 in goods estimated to have been removed by the impromptu salvors. (Here and elsewhere, imputed salvage values of the cargo varied widely.) Meanwhile, the Stonington Wrecking Company had been awarded the contract to remove the cargo intended for France: the freight-car wheels and steel billets, which lay beneath the American goods on all three cargo decks.

There were rumors that Mercantile Wrecking salvors were armed with rifles to shoot do-it-yourselfers, and that a watchman had been placed on the wreck. The government also sought to reclaim the contraband, with limited success. One report said that, when the heat was on, the goods had been scattered “from New Bedford to New Orleans.” The Vineyard’s law enforcement community mostly looked the other way, so the overworked local Coast Guard was called in. According to Lair, a government agent opined that “it would be impossible for the government to recover its losses ‘without undressing most of the populace.’”

The quality of the “dry goods,” an ironic if appropriate description of the wearables coming from the wreck, was variable. An April 7, 1919, article in the New Bedford Standard reported that Zeitz wouldn’t or couldn’t say what the government was paying for the salvaged goods, but that initially the materials had been only rinsed out and dried and were often moldy and “little better than junk.” Now they would be “laundered, pressed and rewrapped in oil paper, sorted and counted into packages as near like the original as possible, and in that way, when they are appraised by the government they are practically as good as new, and will sell for about as much as the original goods.” To accomplish this, Zeitz established laundries in Oak Bluffs and Falmouth. His salvage efforts were successful, and with the proceeds he added to his New Bedford presence by building the Zeiterian Theatre, briefly a vaudeville house and then, as the State Theatre, a movie house. It thrives today as the nonprofit Zeiterian Performing Arts Center.

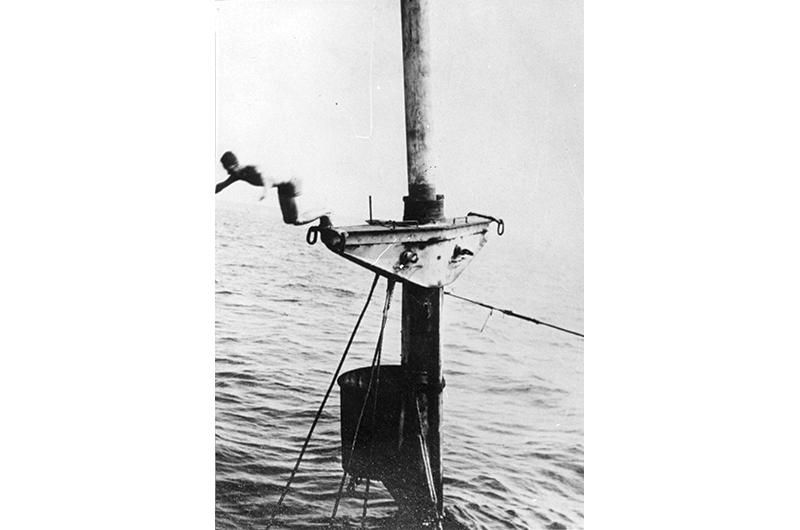

Apparently the do-it-yourself salvors and Mercantile Wrecking got most of the American goods, but the French metals remained. In August of 1920, a Merritt-Chapman wrecking crew appeared in Vineyard Haven with designs on that French cargo and plans to use an electro-magnet to salvage the steel. Three months later the plot thickened: “It is probable that the sale of the hull to the Atalanta Corporation of New York, through Eben D. Bodfish, will be announced in a few days,” the Gazette reported on November 25, “and that the Atalanta Corporation will begin work at once to raise the wreck.” Neither of those schemes ever happened, however, and the Port Hunter, now nearly two years on the shoal, continued to fill with sand driven by the fierce currents over Hedge Fence Shoal. Nor did a plan a year later by Simon Lake, a noted inventor of underwater devices, to raise the vessel come to anything.

A decade and a half passed before, in the fall of 1933, there was once again officially sanctioned activity over the wreck, triggered perhaps by the rising price of scrap iron – or, more intriguingly, by Prohibition’s approaching end. Rights to salvage the wreck had passed to J. E. Doherty, a Boston brewer who believed there was $75,000 worth of fine French brandy aboard, which he planned to salvage as soon as Prohibition ended, meaning the government wouldn’t seize it.

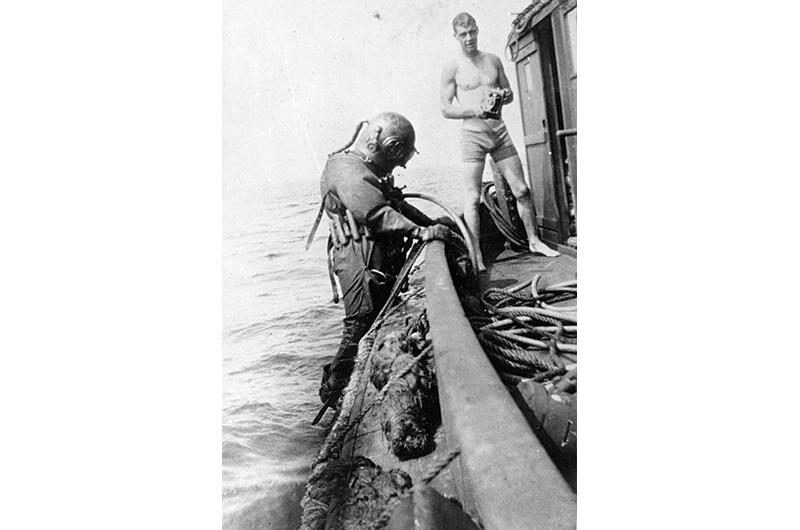

The rumor of precious drinkable cargo began with earlier divers who had been trying to salvage the ship’s single gun as an ornament for Memorial Park in Edgartown. Because of the strong currents, dives were brief affairs at slack tide, and the divers had encountered a locked room that they were unable to enter. Review of blueprints for the ship revealed a “strong room,” rumored to hold as much as $100,000 worth of choice liquors. Stoking this perhaps improbable story were a few cases of whiskey that had been salvaged earlier. When questioned, however, the officer in charge of the ship’s final loading surmised that they were either medical supplies or destined for the officers’ mess. Copies of the manifest listed no liquor. If there was brandy, it’s still there – aging.

Every few years, for the next decade and a half, divers turned up on the Island with plans: to raise the steel, to raise the valuable bronze propellers, to raise the hulk itself. All of them came to naught. Then on a February 1950 morning, a Coast Guard buoy-setter radioed that the wreck buoy that had warned ships of a potential hazard from the remains of the Port Hunter was removed. For decades a mast had protruded tantalizingly above water, but in time the hull had slipped farther and farther off the shoal. At one point a portion of the bow had been dynamited to clear the channel. But now the boat was so deep the Coast Guard no longer considered it a hazard to navigation.

The removal of the buoy might seem to have written finis to the ship’s odd story, but not so. Always there were irresistible stories of gold bullion in the strong room or affixed inside bulkhead walls. On his deathbed, so the story went, the first mate revealed that contraband gold was being smuggled into France. In the summer of 1953, yet another salvage attempt was mounted. Salvors blew the engine room apart searching for it, to no avail. In November of 1960, a plan to use a 119-foot World War II landing craft equipped with a crane to bring up the scrap iron and steel was announced, and went nowhere.

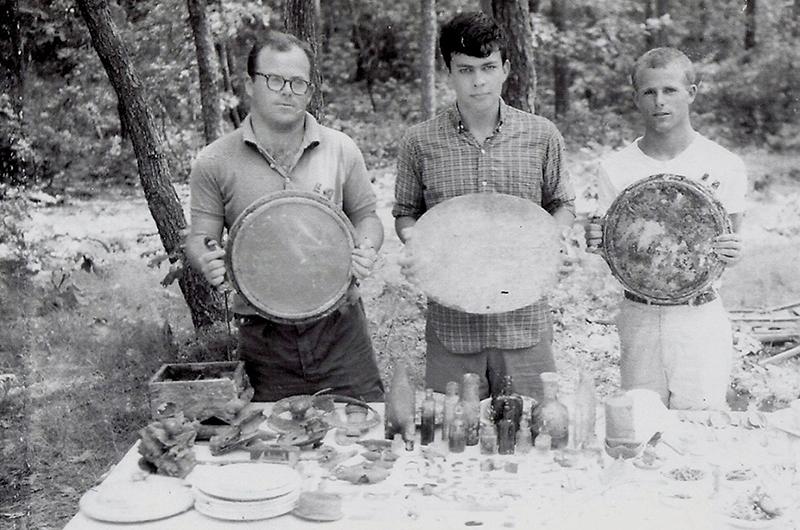

But as with other famous maritime disasters, the legend lives on, and not just on opposite sides of Main Street in Edgartown. As the centennial day of Port Hunter’s sinking approaches, the wreck continues to be a magnet for amateur divers, though strong tidal currents and whirlpools make it challenging, and diving is practical only for an hour around the tide’s turn. The booty of recreational dives over the decades has been artifacts rather than wealth. Starting in 1960 a quartet of young Island divers recovered chinaware and silver, a porthole cover, and unopened bottles of medicine. (See sidebar at right.)

It’s food for thought as you take a Steamship Authority ferry across Nantucket Sound to Oak Bluffs. Who knows, perhaps a few long-wearing leather jerkins still hang in Vineyard closets. And if the price of scrap metal gets high enough….

Those Were the Dives, My Friend...

In 1960, the wreck of the Port Hunter called to a small band of divers. I was one of them. SCUBA equipment (Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus) was very new in those days. There were no diving schools. You read a book, strapped on a tank, and jumped in the water. Arnold Carr and two brothers, Dick and Willy Jones, had done just that. I read the book and jumped in with them. We were now a team – ready to tackle the Port Hunter. I was seventeen.

The day that Arnold and I found the wreck, we swam down a steeply inclined seabed from the top of Hedge Fence Shoal to the bottom at sixty feet. The water got darker and darker. We couldn’t see the ship but we could feel her. Inching forward, we came upon her bow soaring upward in green murk. The emotion was more than I can tell you. Her gun, probably a three-inch cannon, was trained off to port. The crew thought a submarine had torpedoed them. They wanted to sink her.

We explored her cabins. Scattered among the remains of sailors’ bunks were eyeglasses, a set of false teeth, bottles of all sorts, a toothbrush. From other parts of the ship we brought up dinner plates emblazoned with many owners – the Shaw, Savill and Albion Line; the Commonwealth and Dominion Line; the Star Line Limited. She was a bedraggled tramp steamer with hand-me-down flatware.

There were eggcups, though, with “Port Hunter” emblazoned on them. Prizes.

We also discovered World War I trench candles floating under her main deck, the wax still buoyant after all those decades. We brought up large bronze portholes. We gave one to the Dukes County Historical Society (now the Martha’s Vineyard Museum). Another one now hangs on the wall of the Port Hunter restaurant.

One day we found pie-shaped slices of something. When Dick and Willy put the slices in their boat they ignited. Phosphorus. The boys swamped the boat quickly, dousing the fire. Then they bailed her out and went home.

Arnold and I swam deep beneath her dangerously rusted decks, groaning with the weight of tons of cargo. We followed the ship’s keel to find her bow in the beam of our searchlight. We could have been crushed at any moment. We were young and stupid.

For four years the Port Hunter called to us. The dark mysteries of her cargo holds. The haunting sound her broken hull made, vibrating with the current, as if her ancient engines were starting up. The bonding with a diving buddy – knowing that your life might depend on his ability to save you.

She was a time capsule – a shred of history – a war, a crew in jeopardy, the intimate possessions they abandoned.

She was a great adventure and we were just the right age to fully appreciate it.

- Sam Low

5 comments

5 comments

Comments (5)