To say that fly-fishing in salt water is a low percentage game is a considerable understatement. A modern fly-line is one hundred feet or so long. An excellent caster can deliver most of it. An average one a bit more than half. Needless to say, you have to find a way to get within very close range of your quarry.

The flies themselves are a limiting factor also. The shiny plastic lures that line the walls of the tackle shop with hyper-complex paint jobs, holographic tape, and sets of plus-sized treble hooks are the domain of the spin caster. The bucketful of eels and cooler full of bunker that fish can smell from far and wide are the realm of the bait chucker. The fly-fisher, however, intentionally relegates himself to using a handmade (usually self-made) single-hook

fly constructed from a mix of mostly animal fur and feathers, carefully woven together in an attempt to mimic any of a number of creatures from the bottom of the marine food chain.

Fly-fishing, you see, is a process-driven endeavor. It’s less about the end result than how you got there. Saltwater fly-fishermen intentionally start with the deck stacked against them. Something about this inherently uphill battle induces in its participants a compulsiveness that borders on psychoneurotic.

At no time of year is the fly-fisherman’s obsession more glaring than in the fall. There are several factors that contribute to the fervency that is the hallmark of late-season fly-fishing on Martha’s Vineyard. It’s partly that September through October is the only time of year when the Island’s four preeminent inshore game fish – striped bass, bluefish, bonito, and false albacore – are available simultaneously. This diversity challenges fly rodders to employ a wide variety of tactics, in a host of locations, with a broad assortment of targets.

Perhaps the most overarching determinant to the frenzy of fall fly-fishing is finality. In New England we’re not blessed with a year-round coastal fishery. The sport fish that Vineyard fly-fishers covet most are migratory, hence generally unavailable during the winter months. During the fall you’re truly on the clock and the pressure is on. Any fish you catch could well be your last for a great while. Out here, the memories you make in autumn help keep you sane through long, cold Island winters.

With the possible exception of tarpon, striped bass are responsible for more divorces and foreclosures than any fish in the sea. The zealousness that they instill among fly- and conventional fishermen alike is a profoundly strange phenomenon. Some of this fanaticism is attributable to size. Sometimes growing over four feet long and north of fifty pounds, stripers are the largest in the pantheon of nearshore fish in this part of the world. The Martha’s Vineyard Striped Bass and Bluefish Derby record for fly rod striped bass stands at just over forty-two pounds, caught in 1981 by legendary Island fly-fisherman and artist Kib Bramhall. Fly-fishermen Islandwide have spent inky-black autumn nights for the better part of the last four decades wandering beaches from Aquinnah to Wasque pitching flies into stiff headwinds and sideways rain attempting to best this mark. Thus far none have prevailed.

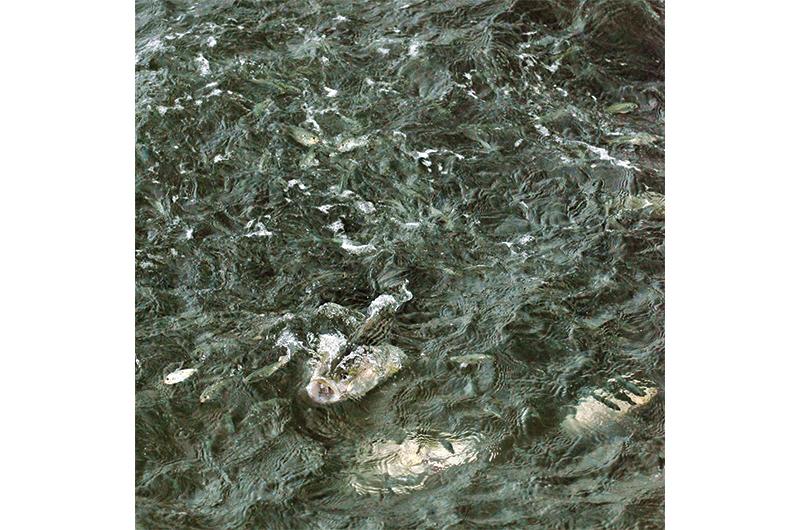

The thought of tangling with a true behemoth keeps the striper freak awake for days at a time. This relentlessness is compounded by stripers’ around-the-clock availability; it doesn’t matter if it’s four in the afternoon or four in the morning, you can always be fishing bass. They are also without question one of the most noble and majestic fish in the Atlantic, often referred to as America’s great game fish. Sliding a proper-sized, fly-caught striped bass onto Vineyard sand is a feeling like none other.

Bluefish are an ornery lot. Were the Island’s nearshore ecosystem a playground, they’d be the bullies. With a maw full of razor-sharp teeth that will plow through all but the strongest shock tippet and a pair of evil yellow eyes, blues patrol local shorelines, rips, and reefs, making quick work of almost anything edible that crosses their path. This propensity for violence makes them a favorite target of many fly-fishermen as they are frequently ready, willing, and able to take a well-presented offering.

In a 2003 article in Saltwater Fly Fishing magazine, author Ed Mitchell described bonito as “ethereal.” You’d be hard-pressed to find a better adjective with which to portray them. Some years plentiful, others scarce, they’re always the belle of the ball. Bass are bigger. Bluefish are stronger. False albacore are faster. But none are wilier. “Bones,” as bonito are known, are truly sly like a fox. Even if you’re lucky enough to hook one, its chances of escape are formidable. Every fly-caught bonito that comes to

hand is a rare and extraordinary treat.

Here on the Vineyard, false albacore cause some of the most maniacal behavior exhibited by anglers anywhere on the coast. Whether it’s the “mosquito fleet” running and gunning their center console boats off State Beach or the unwashed masses sleeping in their cars and bounding up and down the jetty at Lobsterville, “albie” fishermen are truly a sight to behold. Derby widows and disgruntled construction foremen alike have been trying to find a cure for albie fever for decades. As yet, their efforts have been unsuccessful. The likely cause of this lunacy is that of all the fish that visit through the course of the season, albacore spend the least amount of time – usually around six weeks.

Albie fever is also directly related to the fish’s strength-to-weight ratio. Albacore are not terribly big. But, as anyone who’s ever caught one can attest, they fight harder than most fish three times their size. If ever you have the desire to see a large group of grown men in Gore-Tex pants giggling like schoolgirls over a twenty-five-inch fish that weighs little more than five pounds, you needn’t go farther than Cape Pogue Gut on any given morning in early October when the tide is rising.

Whatever the reason, fall fly-fishing on Martha’s Vineyard is an all-consuming and passionate affair that, without fail, every season reaches a fever pitch. At its best it feels like a mad rush of hasty excitement. A dash to the finish line to get your last licks in before the winter comes and the fish swim south, leaving you with nothing but recollections to savor and stories to tell while riding out the off-season. Perpetually yearning to do it all over again.

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)