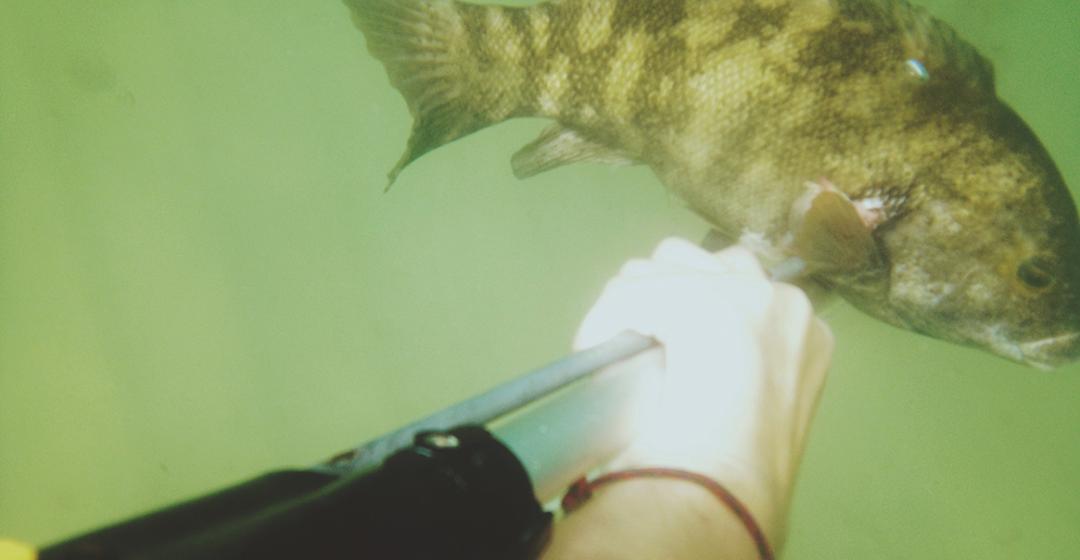

For those Islanders who go down to the sea with spears, there are few things more exciting than spotting a large tautog in the rocky waters off of Martha’s Vineyard. The tautog, or blackfish as it is often called, is a mussel- and crab-crazed bottom dweller that spends extended summers in Vineyard and Nantucket Sounds. Commercially ignored for the most part, tautog are one of the lesser known species of good-eating fish that we still have in abundance here in the Northeast. One reason for their unfamiliarity around the Vineyard dinner table might be that the commercial season for “tog,” as they are often called, only begins in September, and therefore misses the feeding frenzy of summer. Another might be their slimy exterior, which gives them the appearance of an obscure rock creature. But the third reason, and the one that I most suspect to be a factor, is that the best way to get a tautog is to dive headfirst into the Atlantic Ocean and find them where they least expect you.

Tautog are the perfect fish to pursue if you’re just getting into spearfishing, due to their abundance right off the shore. No scuba gear or any sort of breath training is necessary as you are just as likely to find a tautog in five feet of water as you are to find one in twenty feet. A fanatical and lucky “spearo,” as a spearfishing enthusiast often refers to him or herself, could find early migrants hiding among the boulders and rocky outcrops early in the month of May, but most wait until the fish

arrive in greater size and numbers from mid-June to late October. Come winter, the tautog move out to deeper waters offshore, past the reach of even the most extreme spearfishermen geared in their thickest wetsuits.

Summer tautog favor structure and tend to shy away from open sandy bottoms that offer poor places to hide. They try their best to camouflage themselves, hiding in the caves and crevices created by the submerged boulders and rock piles that are plentiful along rocky stretches of the Island’s north shore and at Squibnocket Point. But after a few trips your eyes begin to adjust to the new landscape, and movements that previously went unnoticed start to be perceived. Owing to their predominately stationary food source of mollusks, they tend to be more territorial than, say, a striped bass or bluefish. If left undisturbed they would seemingly stay in a certain rock cropping for a whole summer, or at least until the mussels and crabs were eaten. Like many reef fish, tautog have individual homes that they return to at night, and I’ve heard of some hardened spearos using flashlights to hunt them under the moon.

Spearfishing requires four essential items: fins, mask, snorkel, and speargun. A less essential but good-to-have item is a floating dive flag, especially if you plan to swim more than a few dozen yards off the beach. Better yet, take along a small sit-on-top kayak with an anchor and a cooler, which will give you a floating home base when you need a rest, a cold place to store your catch, and fresh water.

Wetsuits are also important if you intend to spear for longer periods of time or during the spring and early summer. Some people prefer to wear wetsuits all season long, but come August I don’t find it necessary. Remember, the thicker the wetsuit the more buoyant you are, which makes it difficult to dive and maintain your depth. Due to this, many spearfishermen choose to wear a weight belt, which helps them descend and stay along the bottom. No matter the season, it’s nice to have some type of chest protection, such as a rash guard, as your proximity to the rocks can often lead to a scraped-up stomach.

In choosing a spear, you can go as simple as a pole spear, which is essentially a sharpened stick with a rubber band used to propel it. Slightly more complicated is a Hawaiian sling, which works like an underwater slingshot. Proper spearguns, which have a trigger function, are the most complex of the three, but are still completely manageable. Spearguns sometimes have a reel attached to the base, which is useful when spearing larger fish like tuna or mahi that will drag you along with them and can potentially be dangerous if they bring you down too deep. For tautog and most other Vineyard fish, however, reels are unnecessary and will just be a burden, especially if you are new to the sport. I prefer using a thirty-six-inch speargun, which is easily maneuverable around the rocks and plenty powerful for all our inshore species.

As for fins, mask, and snorkel, a set is probably lurking somewhere in every basement or garage on the Vineyard. If you get into the sport, however, you will almost certainly want to upgrade eventually. Good fins, in particular, help eliminate any unnecessary movement of your upper body, which can scare away fish. Fish have a remarkable perceptual ability and tautog are no exception. If they begin to think your descent is due to their presence, they will dart. Movement in general will make them wary, so any form of thrashing will be sure to set off alarms. Therefore, it is best to make your descent as gradually as you can, and if possible, even to swim in a different direction from the fish until you reach the bottom, when you can turn around to surprise them along the ocean floor.

Moving along the surface, you can either wait to descend until you have spotted a fish by peering below, or you can take a deep breath before spotting your game and then hunt along the

bottom. The latter tactic reduces the amount of movement needed to reach the fish, while also allowing a diver to surprise a fish at point blank range if they happen to meet one another while emerging around a rock. This technique is more difficult if you’re just getting into the sport.

Choosing the right day to dive is half the battle for Vineyard spearos. Even in summer, conditions in the Northeast vary greatly day to day, and our water clarity spans from pretty good to extremely poor, with an emphasis somewhere near the latter. Attempting to spearfish during a week that sees heavy winds or waves can be as detrimental to your dinner haul as it is to your morale, and if you are new to the sport you don’t need crappy conditions to deter you. I personally don’t spearfish in waters where I have less than five to six feet of visibility, but when I was just getting started I wouldn’t settle for less than ten. During a perfect week in August that has had no wind, swell, or significant chop, our water clarity can get up to around twenty feet. Sun in the sky, winds out of the southwest, visibility above and below you: this is the holy grail for spearing, and it is during these peak conditions that the joy of the sport can really be experienced.

Though tautog are the easiest to find right off shore, they are not the only fish targeted by Vineyard spearos. Wyatt Bramhall speared a thirteen-pound bluefish off Noman’s Land in 2014, and I watched in disbelief as he got towed through the water like he was on an underwater Nantucket sleigh ride. Hooting and hollering after surfacing, he yelled at the boat to pick him up immediately – being attached to a bloody, thrashing bluefish off Noman’s seemed to have brought some fear into him. I’ve never seen a shark while spearing in Vineyard waters, but did once have a reef shark come and help himself to a fish I kept on the spear too long in the Bahamas.

Black sea bass and flounder are also legal targets during their respective seasons, but striped bass are fully off limits in Massachusetts. If you want to spear a striper you have to go across Buzzards Bay until you reach Rhode Island waters, or travel to New York, New Jersey, or New Hampshire. I prefer to leave the stripers alone no matter what state I’m in. They swim trustingly around you in schools and the thought of betraying that trust with a spear seems almost treacherous. Not to mention that I personally believe tautog are better eating fish as well.

We eat tautog every which way you can think of: grilled whole, filleted and fried, pan seared, or poached. But probably the classic end to a mid-summer spearing party is to stay on the beach, place a few thinly cut fillets in a bowl, squeeze a couple of limes over them, and let them sit for a half hour or so, stirring occasionally. Tautog ceviche requires virtually nothing else but a few tablespoons of any acidic fruit juice, but mix it with some diced onions, peppers, and cilantro, sprinkle on some salt and pepper, and you’d be hard pressed to find anything so fresh or delicious.

Sure, you could catch a tautog from a boat with a rod and reel and the fish would taste just as good, but what you are missing out on by staying dry and above water is the opportunity to become a fish yourself and to get a glimpse of a world that knows nothing of you or your intentions. When spearfishing you are out of your element as a human being; you are a visitor in another world that doesn’t belong to you, a world that is potentially dangerous and completely mesmerizing all at once. The sport’s allure is in the aspect of the unknown, the implicit possibilities that each dive brings.

The following recipe was originally published along with this article:

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)